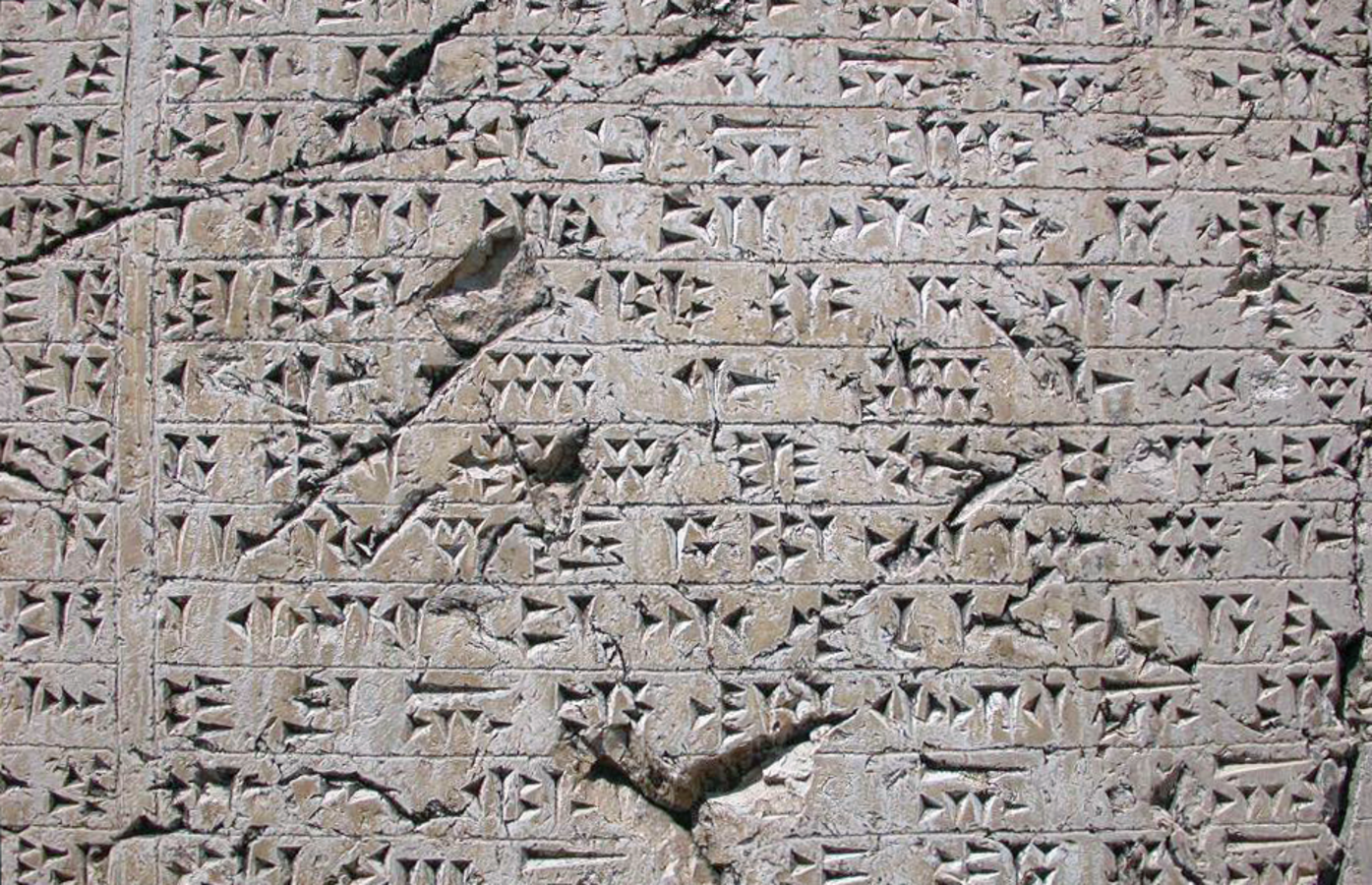

Among the first Assyrian

Fig. 14.1: Mount Ararat

The “Babylonian Mappa Mundi”

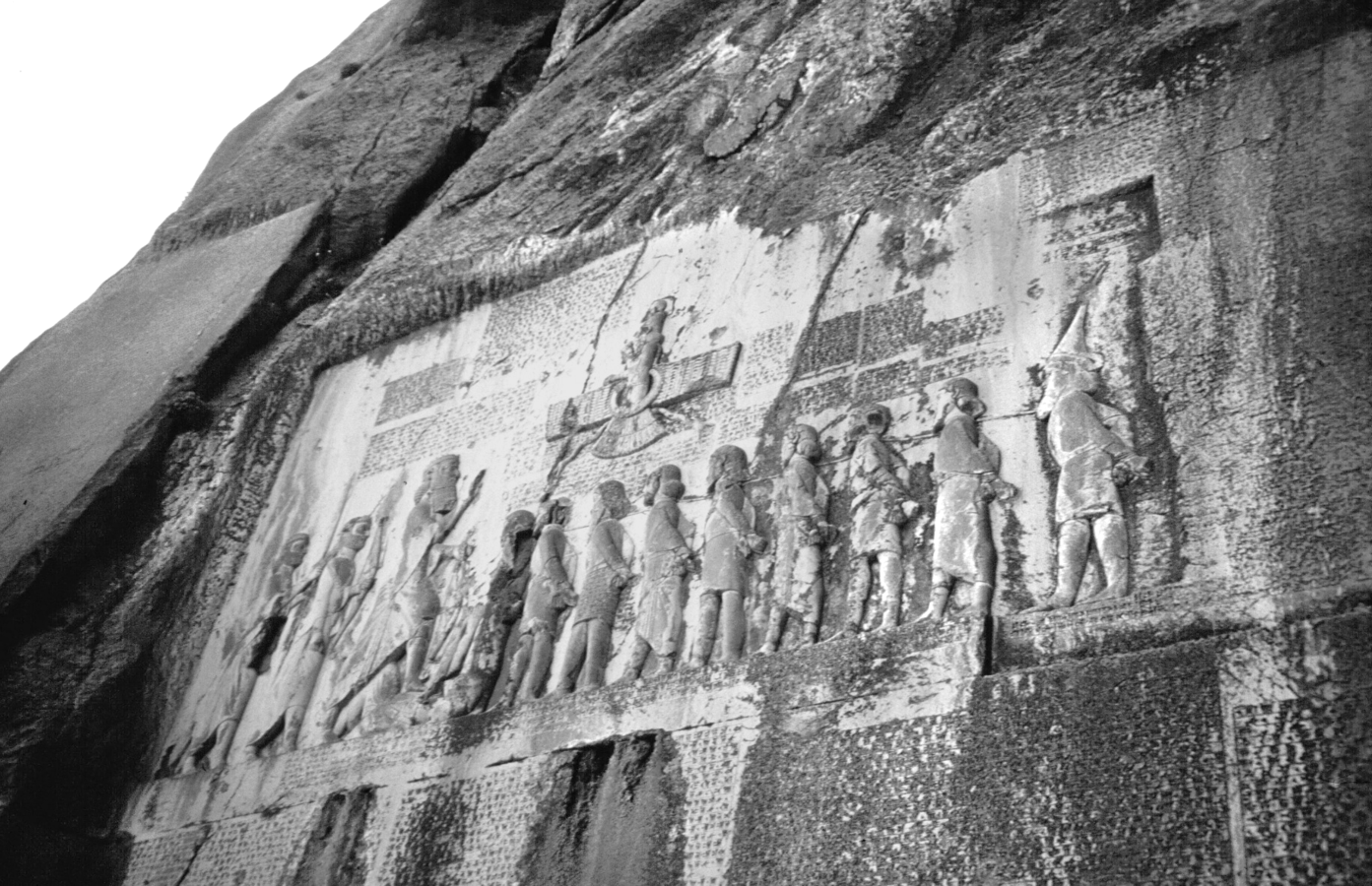

Fig. 14.2: Darius’ relief and inscription at Bisutun

In Eastern Turkey, along the coast of Lake Van

Fig. 14.3: South side of Van Kalesi, site of the Urartian capital Tušpa

14.1 The Discovery of the Urartian Capital

The memory of the magnificent Urartian capital city has stayed alive since the end of the Urartian state, in the second half of the seventh century BCE. The Armenian

This tradition opened the way to the historical research and archaeological discoveries which have continued for almost two centuries now. When, in 1827, the young philosophy professor, F.E. Schulz, arrived in Van to study the ruins of Shamiramakert, he took with him the history of Armenia

I quote now some passages from chapter 16, demonstrating through the example of certain figures the precise topographical and archaeological references found in this text: How after the death of Ara, Semiramis

[…] passing through many places, she arrived from the east at the edge of the salt lake [= Lake Van]. On the shore of the lake she saw a long hill [= Van Kalesi] whose length ran toward the setting sun […] To the north it sloped a little, but to the south it looked up sheer to heaven , with a cave in the vertical rock. […] first she ordered the aqueduct for the river to be built in hard and massive stone [Fig. 14.4] […] on the side of the rock that faces the sun […] she had carved out various temples and chambers and treasure houses and wide caverns [Fig. 14.5] […] and over the entire surface of the rock, smoothing it like wax with a stylus, she inscribed many texts, the mere sight of which makes anyone marvel [Fig. 14.6]. And not only this, but also in many places in the land of Armenia she set up stelae and ordered memorials to herself to be written with the same script.

Such a precise description must be based on reports of ancient travelers or dwellers rather than the works of the classical authors, as some scholar states.

Fig. 14.4: Sustaining wall of the “Semiramis

Fig. 14.5: The mausoleum of Argišti I on the south side of Van Kalesi with the “Khorkhor”-Annals

I would like to provide a short sketch of Urartian history,1 describing the cuneiform

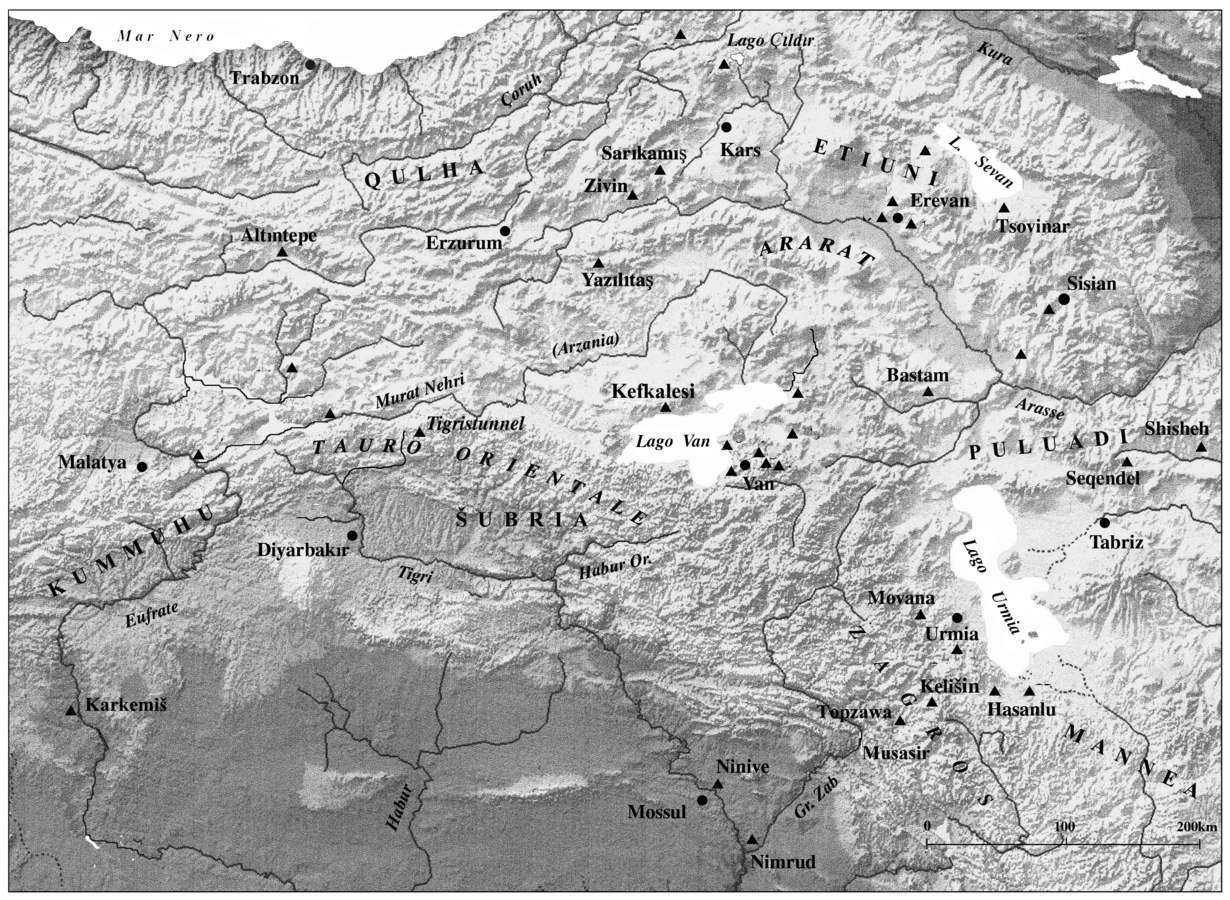

Fig. 14.7: Distribution of the Urartian inscriptions

It is from this place, from Van Kalesi, that, from the end of the ninth century onwards, military expeditions of the Urartian kings set off to conquer an immense territory, stretching as far as the Euphrates

Fig. 14.8: The “Sardursburg” and one of the inscriptions of Sarduri First

The oldest building in Van Kalesi which we can date is the so-called “Sardursburg

Inscription of Sarduri, son of Lutipri, great king, powerful king, king of the universe, king of Nairi,5 king without equal, great shepherd, who does not fear the fight, king who represses rebels. Sarduri says: I have brought here these foundation stones from the city of Alniunu, I have built this wall.6

With this written document, which was discovered in 1827 by Schulz, the pioneer of Urartian research, we have the beginning not only of the history of the Urartian kingdom, but also of written documentation for the entire, immense mountainous region stretching across what are now Eastern Turkey, Armenia

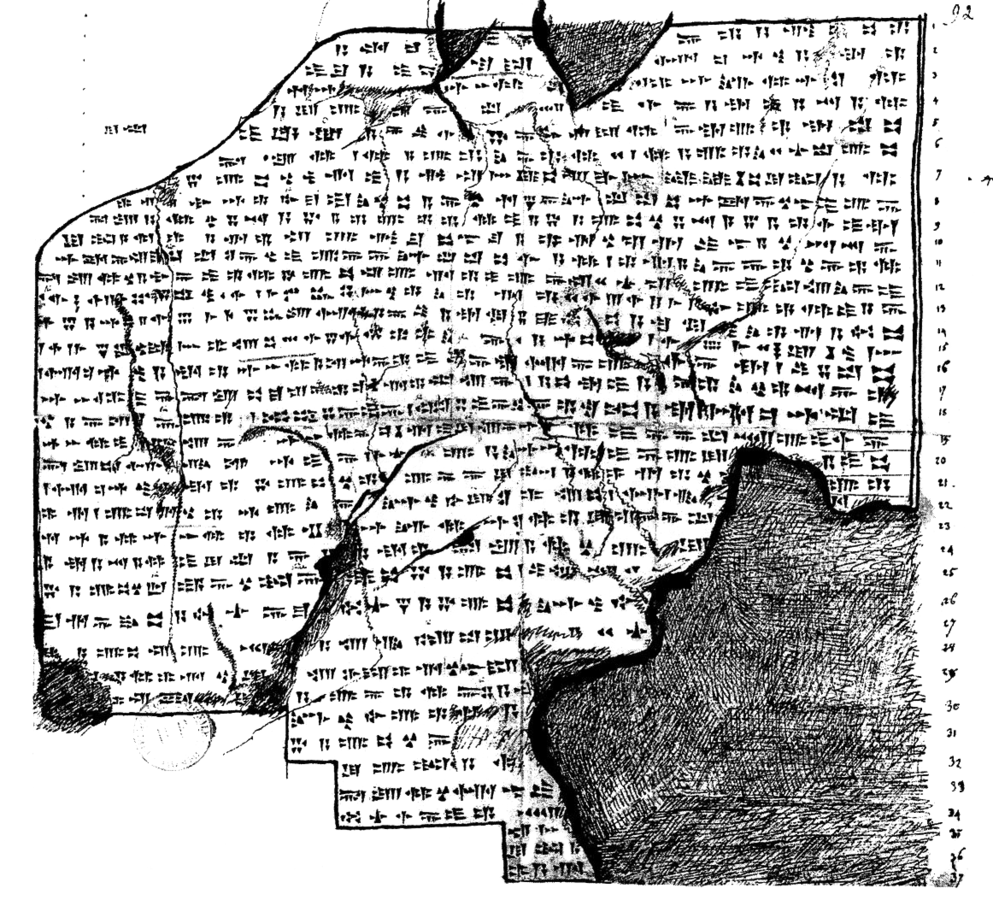

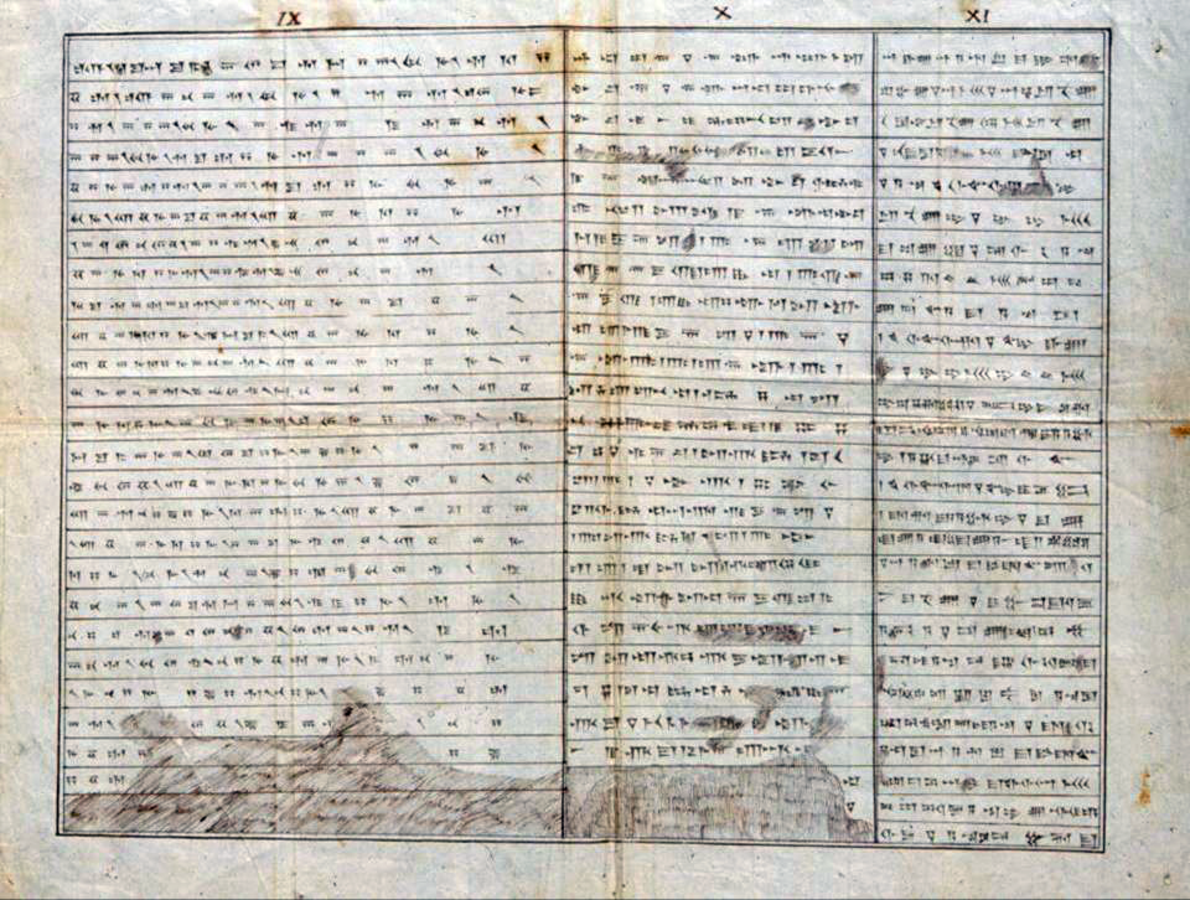

Fig. 14.9: Original copy by F.E. Schulz of the first column of Argišti’s Annals (Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris)

Fig. 14.10: The rock inscription (top) of Xerxes in Van Kalesi and the original copy (bottom) made by Schulz in 1827

The most important achievement of Schulz has been the discovery and autography of 42 cuneiform

The architecture

We have no other written records signed by Sarduri Ist documenting his deeds, but the very fact that he fought against the powerful Assyrian

Fig. 14.11: Assyrian rock inscription on the south side of Van Kalesi

However it cannot be accepted, because there is a huge chronological hiatus between the fourteenth and the ninth century. There are indeed no written records on the Urartian highlands during those five centuries. While the Hittite

Before the foundation of the Urartian state with capital Tušpa

Fig. 14.12: Relief and inscription of Tiglath-Pileser Ist in the “Tigristunnel,” near Lice (East Turkey, October 1984)

The use of Assyrian

(August 1976)

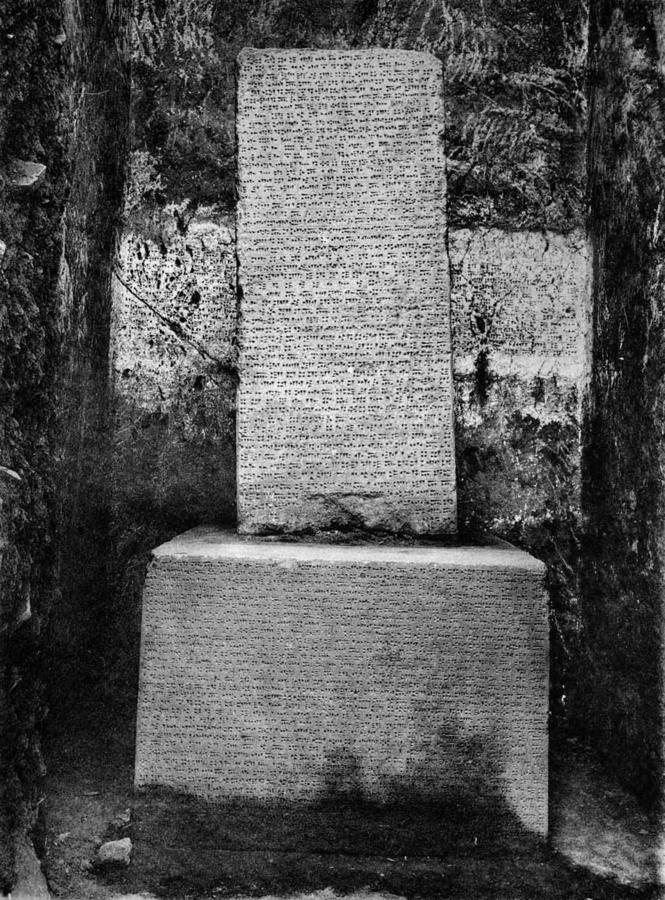

Fig. 14.13: Bilingual stela of Kelišin by Išpuini and Minua

(August 1976)

There are two major written documents testifying to this policy. The first is the Kelishin stela (Fig. 14.13), (Götze 1930; Salvini 1980a), erected on the 3000m. high pass of the Zagros range, which deals with a pilgrimage by Išpuini and his son Minua around 810 BCE to the temple

Fig. 14.14: Rock niche of Meher Kapısı, near Van, with the sacral inscription of Išpuini and Minua

As further proof of this situation we must remember that, in the Assyrian text of the “Sardursburg

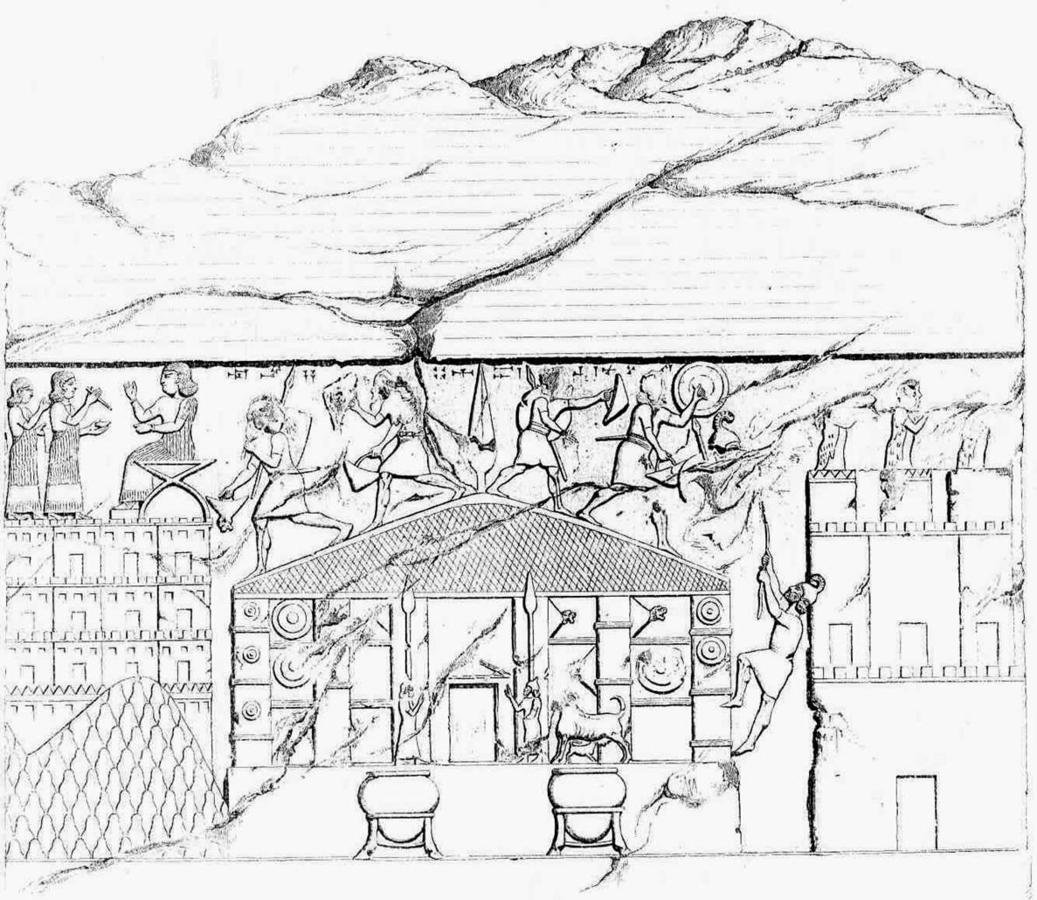

Drawing by E. Flandin (Botta and Flandin 1846–1850, Pl. 142)

Fig. 14.15: Looting of the Muṣaṣir temple by the Assyrians in 714 BCE.

Drawing by E. Flandin (Botta and Flandin 1846–1850, Pl. 142)

The Urartians, in fact, gave enormous importance to Haldi’s

14.2 The Traces of King Minua in the Ancient Capital City of Tušpa

The north wall of the citadel of Van Kalesi reveals four different phases (Fig 14.16). Whilst the upper two are of the Seljuk and Ottoman periods (excluding modern restorations), the two lower parts date to the Urartian era. The great size and quality of the squared-off limestone blocks at the base of the wall show similarities with the “Sardursburg

Fig. 14.16: North wall of the Urartian citadel on Van Kalesi (September 1969)

Fig. 14.17: Fragments of an inscription by Minua reemployed in the citadel wall (from Salvini 1973, Abb. 5)

Various examples show the numerous different applications of the Urartian cuneiform

Fig. 14.18: Inscription of Minua’s

And I would also add what I call the “Fountain of Minua,” declared to be such by the three epigraphs that mark this site along the north foot of Van Rock (Salvini 2008, A 5–58A-C). Its name is taramanili (plurale tantum), connected the Hurrian

The Urartian capital must have had other installations of this practical kind. The presence of a small rock inscription by Minua

14.3 Argišti I’s Records

On the south-western slope of Van Kalesi it is possible today for anyone to visit the rock chambers of Horhor, the main monument left to us by Argišti I (see Fig. 14.5). The long inscription of his annals, decorating the entrance of this rock Mausoleum, is the most extensive document in Urartian cuneiform

({ald)i went out (to a military campaign) with (hi)s weapon, he (defea)ted the country of Etiuni, he (defeated) the land of the city of Qihuni, he threw (them) to Argišti’s feet.Haldi is powerful, Haldi’s weapon is powerful. Through Haldi’s greatness Argišti, son of Minua went out (to a military campaign). Haldi went ahead. Argišti says: I conquered the country of the city of Qihuni, which lies(?) by the lake (= Lake Sevan). I reached the city of Alištu. I deported men and women.

During the same years Argišti began the construction of the city of Er(e)buni, (Salvini 2008, A 8–1 Vo 13–22) which corresponds to the hill of Arin-berd, on the outskirts of Erevan. For this, troops were transferred from the western borders (6600 soldiers from the regions of Ḫate and Ṣupa, the classical Melitene and Sofene),13 with the clear aim of reinforcing control over the territory that today constitutes Armenia

Fig. 14.19: Argišti I’s Annals on the rock of Khorkhor

14.4 The Rock Terrace of Hazine Kapısı by Sarduri II

Fig. 14.20: Hazine Kapısı (Gate of the Treasury). Rock monument on the north slope of Van Kalesi

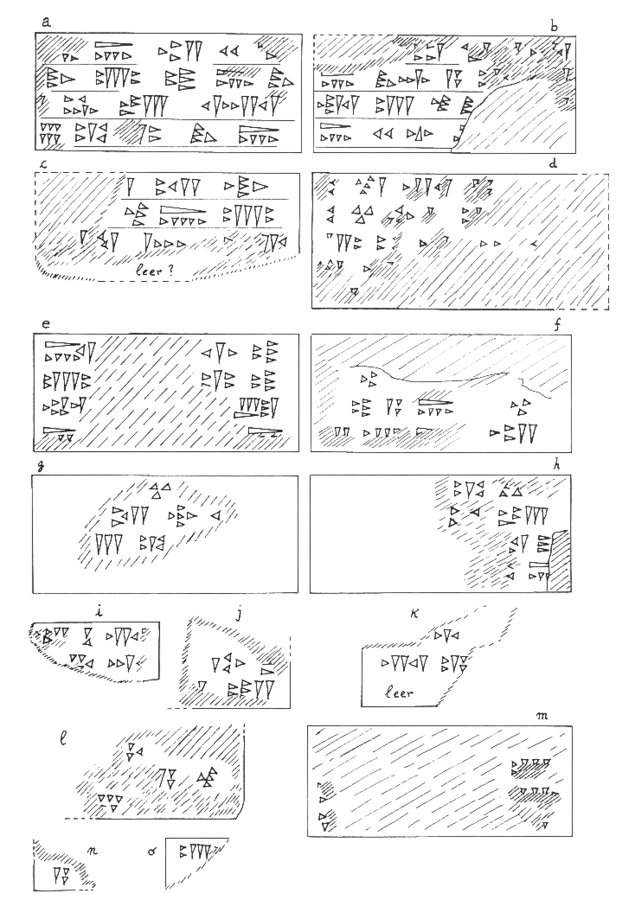

On the north-eastern sector of Van Kalesi, there is an about 40 meters wide terrace cut in the rock (Fig 14.20). This is known as the “Gate of the Treasure” (Hazine Kapısı; Salvini 1995, 143–145) due to the two great niches cut in the rock there. Originally they both held inscriptions, but only in the niche to the right are these partially preserved. This is the famous text of the Annals of Sarduri II, son of Argišti, which was unearthed during the excavations by Marr and Orbeli in 191614 (Fig 14.21). Schulz could see and copy the upper, visible part of the inscription, cut in the rock (Schulz XII = Salvini 2008, A 9–3 I).

This king reigned between 755 and 730 BCE, exactly at the time of the foundation of Rome. Among his military expeditions I quote the conquest of the southern shore of Lake Sevan in today’s Armenia

Fig. 14.21: The Annals of Sarduri II in Hazine Kapısı, at the time of the Russian excavations in 1916 (from Marr and Orbeli 1922)

Euphrates

Fig. 14.22: The rock inscription of Sarduri II on the left bank of the

Euphrates

I mention here only the expedition against Malatya, recalled in the annals, which was recorded on the rock overlooking the Euphrates

A considerable quantity of cuneiform

But Rusa I is known in the cuneiform

His successor Argišti II, from the firm base provided by the consolidated possession of that north-eastern frontier, turned his expansionist aims eastwards, against countries lying both north and south of the Araxes. The new conquests are recorded the stele from Sisian (now in the Museum of Erebuni),17 which shows the Urartian advance towards the Nagorno Karabakh, and on the three rock inscriptions of Razliq, Nashteban and Shisheh in Iranian Azerbaijan (Salvini 2008, A 11–4, 5, 6, with previous literature).

The following period is marked by the reign of Rusa II, the last great Urartian sovereign. During this period, military enterprises were less important then an intense artistic and architectural activity, the greatest testimony to which on Armenian

Fig. 14.23: Façade of the susi temple of Ayanis during excavations (1997)

The Urartians wrote also on different kinds of bronze

Two distinct local hieroglyphic

seventh century BCE

Fig. 14.24: Cuneiform (left) and hieroglyphic

seventh century BCE

The kingdom of Urartu was destroyed in the second half of the seventh century, probably before the fall of Nineveh

With the fall of the centralized Urartian state the cuneiform

| Assyrian kings | Synchronisms1 | Urartian kings |

|---|---|---|

| Shalmaneser III (859–824 BCE) |

quotes Ar(r)amu the Urartian (years 859, 856, 844) |

[no written records] |

| Shalmaneser III (ca. 840–830) |

quotes Seduri, the Urartian (year 832) |

= [written records of:]Sarduri I [* no written records of him] |

|

Shamshi-Adad V (823–811) |

quotes Ušpina (year 820) [no synchronism] |

= Išpuini, son of Sarduri (ca. 830–820) coregency of Išpuini and Minua (ca. 820–810) Minua, son of Išpuini (ca. 810–785/780) |

| Shalmaneser IV (781–772) |

quotes Argištu/i (year 774) |

= Argišti I, son of Minua (785/780–756) |

|

Ashur-nirari V (754–745) |

is quoted by (year 754) |

Sarduri II, son of Argišti (756–ca. 730) |

|

Tiglath-pileser III (744–727) |

quotes Sarduri, Sardaurri (years 743, 735?) |

= Sarduri II |

| Sargon (721–705) |

quotes Ursā / Rusā (years 719–7132) quotes Argišta (year 709) |

= Rusā I, son of Sarduri (ca. 730–713) = Argišti II, son of Rusā (713–?) |

| Sennacherib (704–681) |

[no synchronism] | |

| Esarhaddon (681–669) |

quotes Ursā (year 673/672) |

= Rusā II, son of Argišti (first half of the VII cent.) Erimena (LÚaṣuli ?)3 |

| Ashurbanipal (669–627) |

quotes Rusā (year 652)4 |

= Rusā III, son of Erimena Sarduri (LÚaṣuli ?), son of Rusā III |

| Ashurbanipal | quotes Ištar/Issar-dūrī (year 646/642) |

= Sarduri III, son of Sarduri |

Tab. 14.1: Urartian Chronology

Tab. 14.1: Urartian Chronology

Notes in Table 13.1

1 For the Assyrian

2 The date 713 for Rusa I’s death, instead of the traditional one, 714, is proven by the Annals of Sargon, year 9: see (Fuchs 2012, 419; Lanfranchi and Parpola 1990, SSA V, p. XXVII).

3 We have also to take into consideration the new dendrochronology following which Rusahinili Eidurukai (Ayanis) was built in the second half of the 670s: (Manning et.al. 2001, 2534; Çilingiroğlu 2006, 135).

4 Cf. my attempt to interprete the seal of Erimena and the chronological problems concerning the seventh century (Salvini 2007).

Bibliography

André-Salvini, B., M. Salvini (1992). Gli annali di Argišti I, note e collazioni. SMEA 30: 9-23

- (2002). The Bilingual Stele of Rusa I from Movana (West-Azerbaijan, Iran). SMEA 44: 5-66

- (2003). Ararat and Urartu. Holy Bible and History. In: Shlomo. Studies in Epigraphy, Iconography, History and Archaeology in Honor of Shlomo Moussaieff Ed. by R. Deutsch. Tel-Aviv: Jaffa 225-242

Arutjunjan, N.V. (1953). Chorchorskaja letopis' Argišti I. EV

- (1966). Novye urartskie nadpisi Karmir-blura. Erevan.

Astour, M.C. (1979). The Arena of Tiglath-pileser III's Campaign Against Sarduri II (743 BCE). Assur 2: 1-23

Botta, P.E., E. Flandin (1846–1850). Monument de Ninive. Osnabrück: Biblio-Verlag.

Çilingiroğlu, A. (2006). Erevan. Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies I: 135

Çilingiroğlu, A., M. Salvini (2001). Ayanis I. Ten years' Excavations in Rusahinili Eiduru-kai. Rome: Istituto per gli Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici.

D ' jakonov, I.M. (1963). Urartskie pis'ma i dokumenty. Moskva, Leningrad.

Fuchs, A. (1994). Die Inschriften Sargons II. aus Khorsabad. Göttingen: Cuvillier.

- (2012). Urartu in der Zeit. In: The Proceedings of the Symposium Held in Munich 12.14 October 2007. Tagungsbericht des Münchener Symposiums 12.-14. Oktober 2007 Ed. by Gruber S.Kroll, Hellwag C., H. C., U. Hellwag, U. H.. Acta Iranica 51. Leuven: Peeters 135-161

Gajserjan, V. (1985). Sisianskaja nadpis' Argišti II. VONA

Götze, A. (1930). Zur Kelischin-Stele. ZA 5: 99-128

Grayson, A.K. (1996). Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC (858–745 BC). (The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Assyrian Periods vol. 3). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Haroutiounian, N.V. (1982). La nouvelle inscription ourartéenne découverte en Arménie soviétique. In: Gesellschaft und Kultur im alten Vorderasien Ed. by H. Klengel. (Schriften zur Geschichte und Kultur des alten Orients 15). Berlin: Akademie-Verlag 89-93

Horowitz, W. (1988). The Babylonian Map of the World. Iraq 50: 147-165

Khorenatsi, M. (2006). History of the Armenians, Translation and Commentary on the Literary Sources by R.W. Thomson, Revised Edition,. Ann Arbor: Harvard University Press.

Kleiss, W. (1979). Bastam I. Ausgrabungen in den urartäischen Anlagen 1972–1975. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag.

- (1988). Bastam II. Ausgrabungen in den urartäischen Anlagen 1977–1978. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag.

Lanfranchi, G.B., S. Parpola (1990). The Correspondence of Sargon II. Part II. Letters from the Northern and Northeastern Provinces. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

Lehmann-Haupt, C.F. (1926). Armenien einst und jetzt, II/1. Berlin, Leipzig: Behr.

Malbran-Labat, F. (1994). La version akkadienne de l'inscription trilingue de Darius à Behistun. Rome: CNR. Istituto per gli Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici.

Manning, S.W., B. Kromer, B. K., Kuniholm B. (2001). Anatolian Tree Rings and a New Chronology for the East Mediterranean Bronze-Iron Ages. Science 294(5551): 2532-2535

Marr, N., I. Orbeli (1922). Archeologičeskaja ekspedicija 1916 goda v Van. Raskopki dvuch niš na Vanskoj Skale i nadpisi Sardura vtorogo iz raskopok zapadnoj niši. Petersburg.

Piotrovskij, B.B. (1970). Karmir-blur (al'bom). Leningrad.

Porter, M. (2001). The Helsinki Atlas of the Near East in the Neo-Assyrian Period. Helsinki: Casco Bay Assyriological Institute.

Rollinger, R. (2008). The Median “Empire,” the End of Urartu and Cyrus the Great's Campaign in 547 BC (Nabonidus Chronicle II 16). Ancient West and East 7: 51-75

Salvini, M. (1970). Einige urartäisch-hurritische Wortgleichungen. Orientalia 39: 409-411

- (1972). Le testimonianze storiche urartee sulle regioni del Medio Eufrate. Melitene, Kommagene, Safene, Tomisa. La Parola del Passato

- (1973). Urartäisches epigraphisches Material aus Van und Umgebung. Belleten 37: 279-287

- (1980a). Kelišin. Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 5: 568-569

- (1980b). Un testo celebrativo di Menua. SMEA 22: 137-168

- (1986). Tuschpa, die Hauptstadt von Urartu. In: Das Reich Urartu. Ein altorientalischer Staat im 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Ed. by V. Haas. (Konstanzer althistorische Vorträge und Forschungen 17). Konstanz: Universitatsverlag 31-44

- (1988). Sulla formazione dello stato urarteo. In: Stato Economia e Lavoro nel Vicino Oriente Antico (Atti del convegno dell'Istituto Gramsci Toscano . Milano 270-281

- (1993–1997). Meher Kapısı. Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 8: 21-22

- (1994). The Historical Background of the Urartian Monument of Meher Kapısı. In: The Proceedings of the Third Iron Ages Colloquium held at Van, 6-12 August 1990 Ed. by A. Çilingiroğlu, D.H. French. (Anatolian Iron Ages 3). Ankara: British Institute of Archaeology 205-210

- (1995). Geschichte und Kultur der Urartäer. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- (1998). Nairi, Na'iri. Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 9: 87-91

- (2001a). Alte und neue Forschungen in Van Kalesi. Topographie und Chronologie der urartäischen Hauptstadt Tušpa. In: Lux Orientis. Archäologie zwischen Asien und Europa. Festschrift für Harald Hauptmann zum 65. Geburtstag Ed. by R.M. Boehmer J. Maran. Rahden, Westfalen: Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH 357-367

- (2001b). Inscriptions on Clay. In: Ayanis I. Ten Years' Excavations in Rusahinili Eiduru-kai 1989–1998 Ed. by A. Çilingiroğlu, M. Salvini. Documenta Asiana. Rome: Istituto per gli Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici 279-319

- (2001c). Royal Inscriptions on Bronze Artifacts. In: Ayanis I Ed. by A. Çilingiroğlu, M. Salvini. Documenta Asiana. Rome: Istituto per gli Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici 271-278

- (2001d). Van Kalesi – Sardursburg. SMEA 43: 302-304

- (2007). Argišti, Rusa, Erimena, Rusa und die Löwenschwänze. Eine urartäische Palastgeschichte des VII. Jh. v. Chr.. Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies II: 146-162 and Tables III

- (2008). Corpus dei testi urartei. Le iscrizioni su pietra e roccia (CTU). Rome: CNR, Istituto di studi sulle civiltà dell'egeo e del vicino oriente.

- (2009). Die Ausdehnung des Reiches Urartu unter Argišti II. (713-ca. 685 v. Chr.). In: Giorgi Melikishvili Memorial Volume Ed. by I. Tatišvili, M. Hvedelidze, M. H.. Caucasian and Near Eastern Studies 8. Tbilisi: Ivane Javakhishvili Institute of HistoryEthnology 203-227

- (2011). Sarduri. Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 12: 39-42

Schmitt, R. (1980). “Armenische” Namen in altpersischen Quellen. Annual of Armenian Linguistics 1: 7-17

Schulz, F.E. (1840). Mémoire sur le lac de Van et ses environs. JA 9: 257-323

Seidl, U. (1994). Achaimenidische Entlehnungen aus der urartäischen Kultur. In: Achaemenid History VIII. Continuity and Change. Proceedings of the Last Achaemenid History Workshop, April 6-8 1990, Ann Arbor-Michigan Ed. by H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg, A. Kuhrt, A. K.. Leiden: Brill 107-129

- (2004). Bronzekunst Urartus. Beschriftete Bronzen

Thureau-Dangin, F. (1912). Une relation de la huitième campagne de Sargon (714 av. J.-C.), TCL III. Paris: P. Geuthner.

Wilhelm, G. (1986). Urartu als Region der Keilschrift-Kultur. In: Das Reich Urartu. Ein altorientalischer Staat im 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Ed. by V. Haas. (Xenia 17). Konstanz: Universitätsverlag

Footnotes

See (Salvini 1995). In the Appendix, see the Urartian Chronology with the Assyrian synchronisms.

See (Salvini 1986; Salvini 2001a).

Map 1:2.000.000, by TAVO B IV 12, Östliches Kleinasien. Das Urartäerreich (9. bis 7. Jahrhundert v. Chr.), 1992; (Porter 2001).

Cf. the measurements of the blocks by M. Salvini (2001d, 302–304).

About the tradition of the toponym Nairi, see (Salvini 1998, 87–91).

Analysis and translation: (Wilhelm 1986, 95–113; Salvini 2008, A 1-1a-f).

See (Schulz 1840, 257–323).

RIMA 2, N° 15 (Tiglath-pileser I); RIMA 3, N° 21–24 (Shalmaneser III). See also the discussion about the topographical position of the different inscriptions and reliefs by (Salvini 1988, 270–281).

RIMA 2, N° 16.

The sources are the texts of Išpuini (Salvini 2008, A 2) and those, more important, of Išpuini and Minua (Salvini 2008, A 3).

First copied by F.E. Schulz in 1827 (see above fn. 7) [Schulz II-VIII]. Translated by Arutjunjan (1953); collated by (André-Salvini and Salvini 1992).

See (Salvini 1972, 142–144, 279–287). After collation of the badly damaged rock inscription of Rusa II in Kaleköy near Mazgirt (Salvini 2008, A 12–6), I could read KURṣ]u-pa-a, which confirms the position of the Urartian Ṣupa(ni), being the oldest quotation of the classical Sofene.

See (Marr and Orbeli 1922). Unfortunately the stela and the basalt basis with the main text of the annals were broken in pieces by the vandalistic action of the local people.

See (Astour 1979; Salvini 2011).

See (André-Salvini and Salvini 2002), with previous literature; (Salvini 2008, A 10–3, 4, 5).

KUKN 411 = (Salvini 2008, A 11–3); (Haroutiounian 1982). See also the new edition of the Reverse (Gajserjan 1985, 67–79) and (Salvini 2009).

See my dechifering in (Çilingiroğlu and Salvini 2001, 293–303).

Robert Rollinger (2008, 51–75), maintains that the Urartian state survived long after the fall of Assyria, and continued to exist as an independent political entity until the conquest by Cyrus the Great.