Chapter structure

- 4.1 Domesticated Silkworm Breeding and Wild Silk Production: The Song-Yuan Period

- 4.2 State Interference and Change: Sericulture in the Late Ming and Early Qing Period

- 4.3 Technical Developments in Moriculture

- 4.4 The Wild Silk Industry: Individual and Imperial Campaigns

- 4.5 From Wild Forests to Planned Wild Forest Plantations for Sericulture

- 4.6 Conclusion

- References

- Footnotes

During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) a combination of agricultural policy carried out by the throne and technical progress led to the concentration of sericulture in particular regions such as the Lower-Yangzi Delta, the Red Basin (or Sichuan Basin), the Pearl River Delta and the Lower-Yellow-River Delta.1 By the late Ming dynasty, this concentration was particularly pronounced in the lower-Yangzi Delta, as the silk produced here was indispensable for the making of refined silk goods. One century later, the state began to take an interest in wild silk production and Emperor Qianlong (1711–1799, r. 1735–95) even officially promoted its production in 1744. These developments occurred against the background of fiscal reforms and a flourishing maritime trade.

The history of the Chinese silk industry in these areas has long interested modern historians. Many consider that sericulture centralized in these particular regions because it complemented the expansion of cotton, which had been introduced into the region of Jiangnan around the mid-thirteenth century during the late Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279). Sericulture was arduous, risky, and more technically demanding than cotton culture, but market demands for raw silk and silk products rose incessantly throughout the Ming and Qing (1644–1911) eras. Due to technical progress in sericulture, productivity increased and thus prices for raw silk fell.2 Soon after 1684, when maritime trade was re-opened, domestic silk prices skyrocketed. By the mid-eighteenth century the Imperial Weaving Manufactures whose prices were regulated by the Imperial Instructions were hit by a dramatic rise in the price of their raw materials.3 Demographic shifts and a lack of cultivable land lead to Qing official interest in wild silkworm pasturing, that is, a practice whereby natural forests were used to grow wild silkworms (from here on abbreviated as “wild pasturing”).

In the second half of the twentieth century, the “golden age” of studies on the history of the Chinese silk industry, few scholars dealt with sericulture and even fewer with technical progress during the Ming-Qing period. Dieter Kuhn, like many others, took the technical achievement of the Song-Yuan period to be the model for later eras, assuming that Ming-Qing era silk workers did not add any major improvements of their own. This paper focuses on the technical revolution in sericulture during the late Ming and early Qing period. Emphasizing regional variations and delineating technical evolution in mulberry plantations, silkworm breeding and silk reeling as well as broadening the view to include wild pasturing, provides new insights into the evolution of Chinese silk production after the sixteenth century.4

4.1 Domesticated Silkworm Breeding and Wild Silk Production: The Song-Yuan Period

Several species of caterpillar from the Bombycidae and Antherea

families produce silk viable for textile manufacture. Whilst elite

writing singled out the Bombyx mori (named

formally household silkworms, jiacan

The introduction of advanced sericultural know-how and of a

species of mulberry from Shandong—known in Chinese literature as the

Lu-mulberry tree (Lu sang

The climate of the lower Yangzi Delta was humid and warm and the

region also experienced annual flooding which deposited silt on the

soil, effectively fertilizing the land. With the fall of the

northern capital Kaifeng and the retreat of the Huai River to the

south, the Song government had to invest in draining swamps and

building dikes in order to create new rice fields to feed the

population. Chen Fu

The Essential Treaties on Agriculture and

Sericulture (Nong sang jiyao

Chen Fu was an atypical handbook author who, in his attempts to

spread advanced agricultural and sericultural knowledge, wrote down

his own personal experience and developed guidelines for farmland

management appropriate to Southern China, mulberry cultivation and

silkworm breeding.14 In contrast, most literati provided instructions by

gathering existing documents, together with information from

experienced farmers and their own observations. The Essential Treaties represented the later format:

it gave advice on quality of leaves, frequency and timing silkworm

feeding and passed on knowledge on cultivation and fertilization.

From these sources we know that farmers believed that feeding

caterpillars abundantly during the last stage before pupation

increased both the quality and quantity of silk thread. The

guidelines also suggest that lady silkworm farmers (canmu

White coloration suggests they are starting to eat; those with a blue color need to be abundantly fed; those with a wrinkled skin are hungry; stop feeding those that start turning yellow little by little.15

By the early fourteenth century, sericulture farmers in Jiangnan

grasped that moving silkworms during the moulting stages could

inflict injuries. As healthy silkworms quickly clamber onto fresh

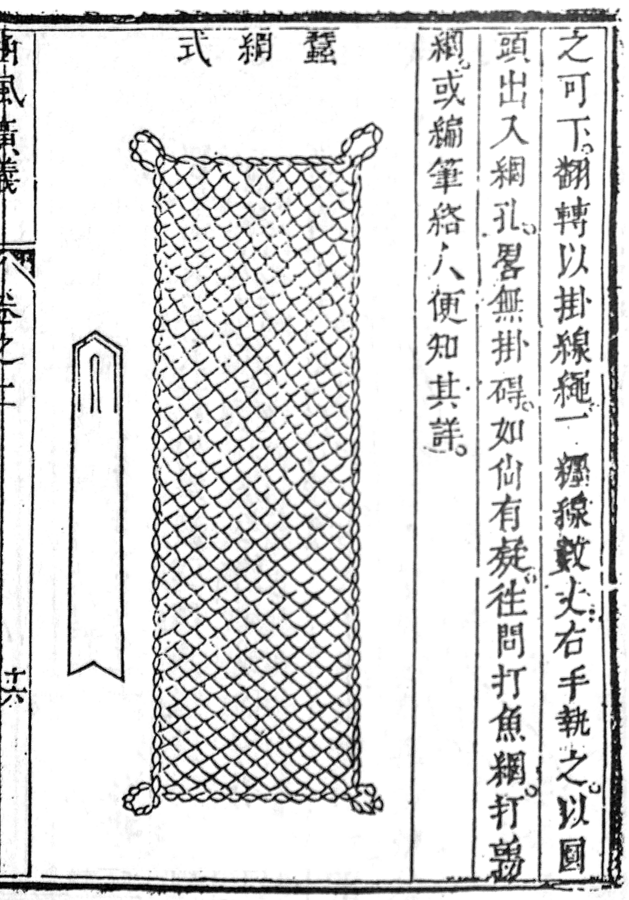

leaves, Wang Zhen 王禎 recommended using a silkworm net (canwang

Fig. 4.1: Drawing of a silkworm net (canwang

The Essential Treaties says nothing about mulberry feeding quantities, preferring to stipulate the spatial requirements for caterpillars at different stages:

[…] place three ounces (circa 120 g) of new-born silkworms on a basket. When they reach the age for cocooning, divide them into thirty baskets. One ounce of new-born caterpillars requires ten baskets of silkworms for cocooning. The basket is one zhang (circa 300 cm) in length and seven feet wide (circa 210 cm).17

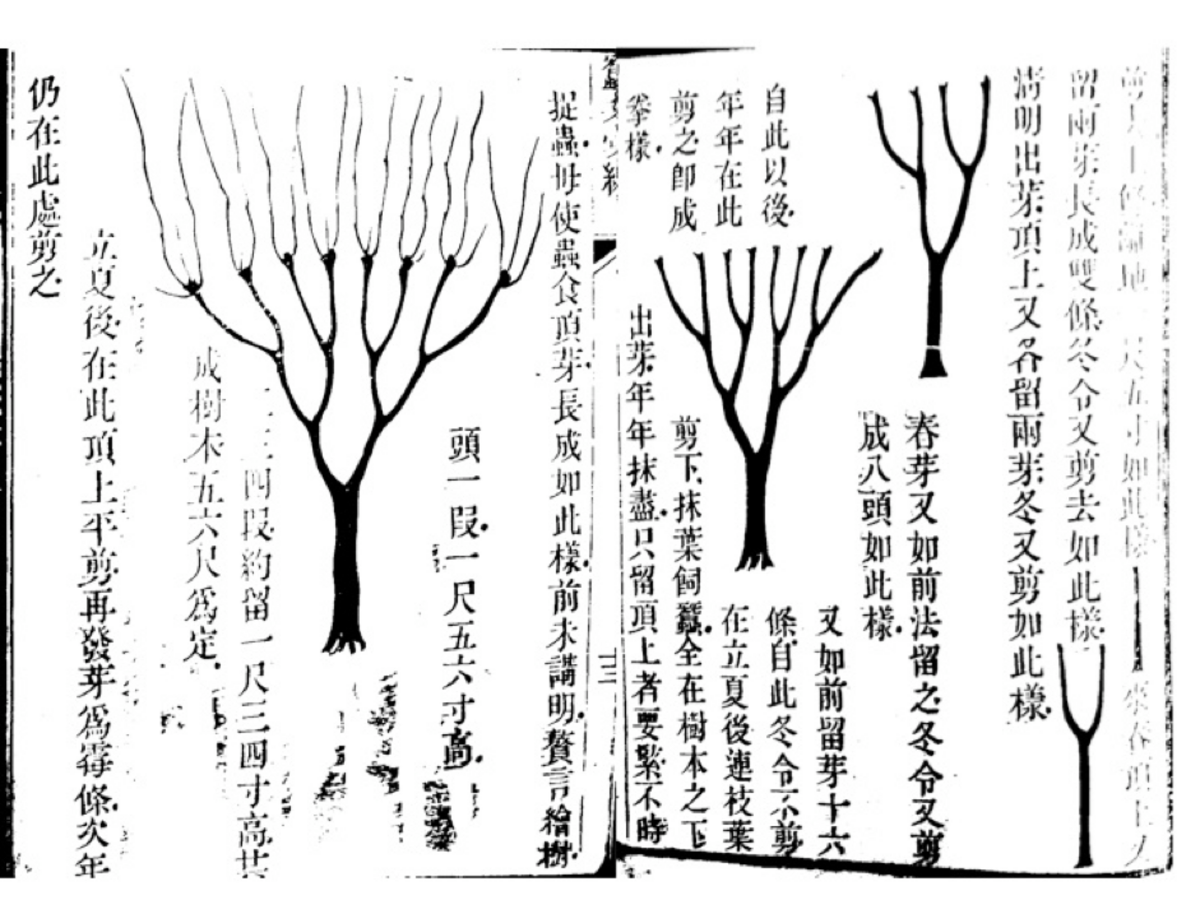

Such a rule of thumb was useful for silk farmers who needed to provide sufficient space in their houses for the silkworms to grow (Figure 4.2).18

Fig. 4.2: Silk farmer placing mulberry leaves on silkworm net, Haining

4.2 State Interference and Change: Sericulture in the Late Ming and Early Qing Period

Upon his accession to the throne in 1368, Emperor Taizu, Zhu

Yuanzhang

People with land of between five to ten mu must cultivate half a mu (ca. 600 m2) each with mulberry trees, hemp,19 and cotton plants. Owners of more than ten mu have to double this number. The levy for hemp land is eight ounces per mu; four ounces per mu for cotton land. Mulberry cultivation will be taxed from the fourth year [of plantation]. Not cultivating mulberry trees has to be compensated with a piece of plain tabby; not planting hemp or cotton costs one piece of hemp and cotton cloth each.20

Cotton cultivation was thus integrated into the agricultural policy by imperial edict. In 1381, Emperor Taizu restricted merchant families to wearing cotton and hemp attire, whilst allowing peasant families to wear silk gowns in an attempt to boost agriculture.21 In 1394, the Ministry of Public Work once again encouraged mulberry and jujube cultivation alongside cotton and hemp.22

Alongside the state’s vigorous promotion of silk, a flourishing trade also positively influenced sericulture. The inhabitants of prefectures of Jiaxing, Hangzhou, and Huzhou specialized in sericulture. By the Jiajing (1522–66) period, “the soil was available for mulberry trees” at Shimen (modern Zhejiang province) and “cocoon silk was marketed and merchants came from all over the world on the fifth lunar month of every year to purchase silk. They accumulated gold like stones.”23 An increasing number of people dressed in silk. Emperor Chongzhen (1627–44) disliked luxuary clothing. Mandarins in Court thus dressed in wild silk instead of the refined silk produced by Bombyx, and that provoked a craze for wild silk.24

Another important influence was an increase in global trade. European merchants, but also Japanese and South Asian traders, flocked to Ming ports through the newly opened maritime trade or inland trade routes.25 Foreign trade built on existing structures and stimulated the established private silk weaving workshops around maritime ports. In Quanzhou the Ming had already established state-owned Regional Weaving Manufactures (1438).26 Nevertheless, it is important to note that, even though generations of officials had tried to promote sericulture, the silk produced in these regions was inferior in quality and quantity and weavers had to import raw silk from Zhejiang province.27

Since the foundation of the Ming, prefectures in the Jiangnan

region had borne the heaviest fiscal weight in the empire,28 because of the occupation by Zhang Shicheng

In the early Qing period, Yan Kaishu

Such innovations included new breeds of silkworms and new

techniques. Farmers in the Jiangnan region bred older silkworms

directly on the ground—the “silkworm farm on earth” (dican

Fig. 4.3: Silkworm breeding on earth, dican

4.3 Technical Developments in Moriculture

The Ming-Qing dynasties developed and spread the techniques of

growing dwarf mulberry trees which facilitated leaf picking and

favored leaf growing: moriculture became a proto-specialized

activity. By comparison in the sixth century, Jia Sixie

In the Huzhou region, two main types of dwarf trees emerged: a

“fist” shaped tree (quansang

Fig. 4.4: Guide to pruning mulberry trees at various stages of growth

(r. to l.). Quansang

By the Ming–Qing period, Huzhou silk farmers had succeeded in

cultivating high quality mulberry trees (Hu

sang

The Zhejiang gazetteer identifies Hu as

actually a breed of the Jing mulberry,37 whereas the Qing literati, Bao Shichen

Because the mulberry tree prefers loosened soil, the cultivation must be times four and the depth more than one foot. As the mulberry prefers fertilizer, heap silkworm litter as well as bean dregs and compost made of manure and straw [around the roots]. Since mulberry hates gravel and weedy land, mulberry must be planted on plain and perfectly weeded ground. Because they [farmers] know how to prepare the soil according to the nature of mulberry tree, the latter produces many big and thick leaves.38

Compared to the Song-Yuan period, materials for fertilizing had multiplied by the late Ming era:

Heap fertilizer around a mulberry root, use excrement, silkworm litter, ash from rice straw, mud from gutters or ponds and fertile earth. Use algae, or cotton seeds as heap fertilizer at the beginning of the culture.39

Mud from riverbeds was highly valued as a free and abundant fertilizer: “if a mulberry tree is not flourishing, it lacks river mud.”40 The practice also ensured the regular clearing of sediment.41 However, many Qing authors said to “stop fertilizing the mulberry tree at least half a month before leaf-picking” and not to feed silkworms with leaves picked from recently fertilized mulberry trees, because they considered that these leaves would be harmful to silkworms.42

Advances in moriculture were hence central to increased yields

and quality of raw silk. One of the main reasons silk farmers in the

Jiangnan region were able to produce the best quality silk in the

empire, must have been the culture of Hu mulberry trees.43 Zhang Kai

4.4 The Wild Silk Industry: Individual and Imperial Campaigns

Since antiquity, Chinese historiography had hailed the appearance of wild cocoons as a good omen.45 Further development of wild silk production relied on the initiatives of farmers and the efforts of some civil officials, until Qing emperors included wild silk onto the official list of textile production encouragement, including domesticated sericulture.46

Sun Tingquan

Liu Qi

In 1738, Chen Yudian

[…] the reputation of Zunyi silk cloth [zunchou遵紬 ] can finally compete in quality with refined silk goods from Wu [the region roughly equivalent to the plain of Lake Tai] and silk clothes from Shu [an abbreviation of Sichuan] for a high price. Merchants from Shaanxi and Shanxi, as well as those from Fujian and Guangdong, roll [into Zunyi] during the cocoon harvests seasons and leave with bundles of silk.51

Chen Yudian’s campaign happened to coincide with that of Chen

Derong

In 1744, following the suggestion of the provincial inspector of

Sichuan Jiang Shunlong

Chen Hongmou’s case illustrates how the central state thrived on

local efforts. When Chen, for instance, arrived at his post in

Shaanxi, local scholar, Yang Shen

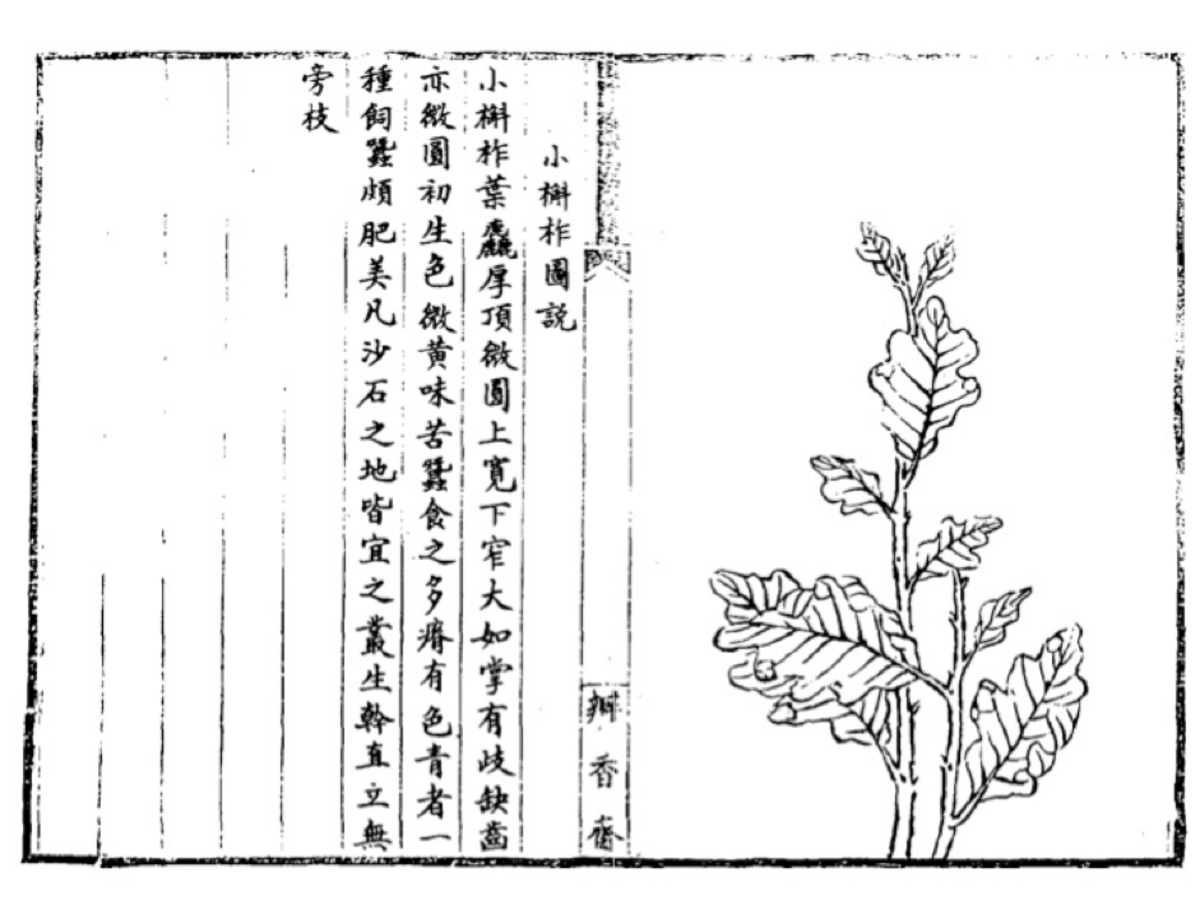

Fig. 4.5: Illustration of a sample of the Beech Family (Xiao hu zuo

In the following years, several handbooks on wild silkworm

pasturing appeared. Han Mengzhou

4.5 From Wild Forests to Planned Wild Forest Plantations for Sericulture

From the end of the 1750s on, civil officers promoting wild

pasture also started to plant suitable trees. For instance, Aertai

Due to the lack of cultivable land and the need to assure

people’s livelihood, the government considered wild silkworm

pasturing an ideal way to exploit formerly “useless” land.

Furthermore, in the early years of Daoguang Emperor’s reign

(1821–50) the administration restarted encouraging the exportation

of raw silk to balance the silver deficit in the Imperial Treasury,

thus stimulating a new rise in wild silkworm pasturing, as well as

the planting of trees for wild silkworm feeding. As well as

Shandong, Guizhou rose to prominence in this trade, as wild silk

making had been established there since the beginning of Emperor

Qianlong’s reign. In the early Daoguang era (1820-50), Chen Yudian’s

model was imitated by the judicial commissioner in Guizhou, Song

Rulin

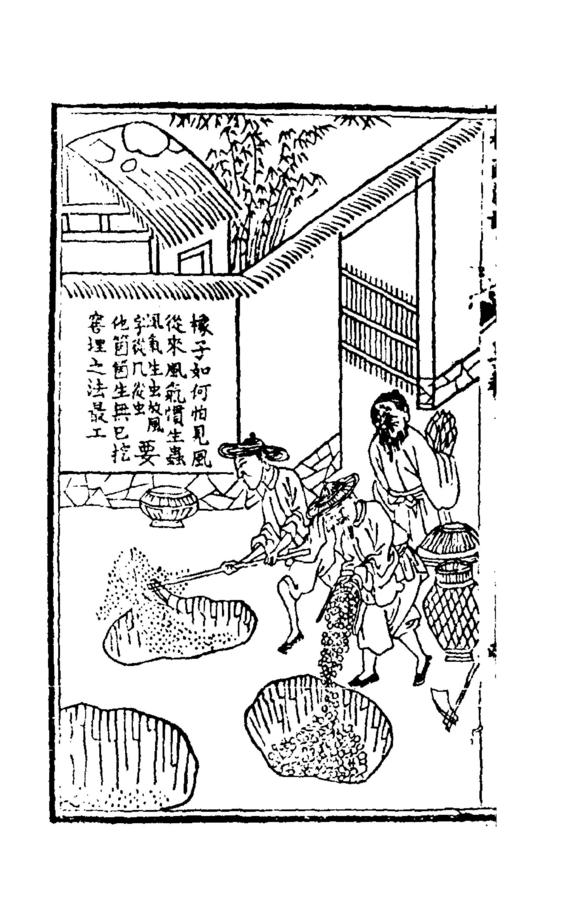

Emphasis was placed on oak silkworms in Anping, Guizhou where the

magistrate Liu Zuxian

Fig. 4.6: Farmers digging holes to store oak seeds. Liu, Zuxian

Many of these campaigns in the south were abruptly interrupted by

the Miao rebellion in late 1850s. It was not until 1870, that the

prefect of Liping, Yuan Kaidi

4.6 Conclusion

During the late Ming and early Qing periods, Jiangnan asserted its leading role in sericulture thanks to advanced techniques in mulberry culture, silkworm breeding, silk reeling, and soil improvement. The area featured a growing population with skilled labor and thriving foreign and domestic markets. By the late fifteenth century, farmers around Lake Tai were pursuing intensive sericulture and providing goods of outstanding quality. Increased high-quality productivity in Jiangnan put pressure on other regions where their sericulture know-how was relatively rudimentary and, freed from tax payments in silk and silk goods required by governments, Chinese farmers switched from mulberry cultivation to other crops, such as cotton, fruit trees and even the newly-introduced tobacco.

Silver inflow from Mexico via the maritime trade led to fiscal reforms generally known as the Single Whip Law, which freed people to grow the most profitable agricultural crops. At the same time, modification in clothing regulations further stimulated market demand for silk clothes but in more simplified styles. Maritime trade with European nations incited the development of sericulture in the Pearl River Delta, despite its substandard quality. Still, the demographic pressure on land was intense and wild silk pasturing thus became valued by the government. Officials attempted to capitalize on formerly “value-less” forests in order to provide textiles to clothe the people and the growing international market of wild silk. However, wild silk pasturage only took root in poor regions, such as Ningqiangzhou in Shaanxi, and Guizhou, where local people had difficulty finding more profitable activities.

References

Bao, Shichen 包世臣 (1968). Qimin sishu 齊民四術 [Four Techniques for the Welfare of the People]. In: An Wu sizhong 安吳四種 [Four Categories of Anwu]. Taipei: Wenhai chubanshe.

Chen, Fu 陳敷 (1966). Nongshu 農書 [Book of Agriculture]. Taipei: Yiwen yinshuguan.

Chen, Guan 成瓘 (2004). Daoguang Ji’nan fuzhi 道光濟南府志 [Local Gazetteer of Ji’nan Prefecture (Daoguang Era)]. In: Zhongguo difangzhi jicheng 中國地方志集成 [A Collection of Chinese Gazetteers]. Nanjing: Fenghuang chubanshe.

Chen, Hongmou 陳宏謀 (1995). Guangxing shancan xi 廣行山蠶檄 [Broadly implement the culture of mountain silkworms]. In: Xuxiu sikuquanshu 續修四庫全書. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

Chen, Kangqi 陳康祺 (1987). Langqian jiwen 郎潛紀聞 [A Record of What I Have Heard]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju.

Cheng, Dai’an 程岱葊 (1995). Xi Wu canlue 西吳蠶略 [Primer on Western Wu Sericulture ]. In: Xuxiu sikuquanshu 續修四庫全書. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

Fan, Jinmin 范金民 and Wen Jin 金文 (1993). Jiangnan sichou shi yanjiu 江南絲綢史研究 [A Study of the History of Silk in Jiangnan]. Beijing: Nongye chubanshe.

Fang, Ding 方鼎 et al (1967). Jinjiang Xianzhi 晉江縣志 [Local Gazetteer of Jinjiang County]. In: Zhongguo fangzhi Congshu 中國方志叢書 [China Local Gazetteers]. Taipei: Chengwen chubanshe.

Fang, Xuanling 房玄齡 et al (1986). Jinshu 晉書 [History of Jin Dynasty]. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

Gao, Shumei 高樹枚 and Gao Shuhuan 高樹桓 (1915). Lidai quannong shilue 歷代勸農事略 [A Survey of Agriculture Encouragement History in China].

Gaozong shilu 高宗實錄 [Veritable Records of Emperor Gaozong (1736–1795)] (1986). In: Qing shilu 清實錄 [Veritable Records of the Qing Dynasty]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju.

Gu, Cong 顧樅 (2004). Xifeng xianzhi 息烽縣志 [Gazetteer of the District of Xifeng]. In: Zhongguo difangzhi jicheng 中國地方志集成 [A Collection of Chinese Gazetteers]. Nanjing: Fenghuang chubanshe.

Hada, Qingge 哈達清格 (1970). Tazigou jilue 塔子溝紀略 [Brief Records of Tazigou]. In: Congshu jicheng xubian. Taipei: Yiwen yinshuguan.

Huang, Shengzeng 黃省曾 (1966). Canjing 蠶經 [Silkworm Classic]. In: Congshu jicheng jianbian. Ed. by Wang Yunwu 王雲五. Taipei: Taiwan shangwu yinshuguan.

– (1995). Canjing 蠶經 [Silkworm Classic]. In: Nong sang jiyao 農桑輯要 [Essential Compilation of the Agriculture and Sericulture]. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

Huang, Zhaizhong 黃宅中 and Zou Hanxun 鄒漢勛 (1849). Daoguang Dading fuzhi 道光大定府志 [Local Gazetteer of Dading Prefecture (Daoguang Era)].

Ji, Fagen 嵇发根 (2008). Husang de qiyuan jiqi neihan kaolun “湖桑”的起源及其內涵考論” [The Origins and Meanings of “Husang”]. Nongye kaogu (1):185–86.

Ji, Zengyun 嵆曾筠 (2004). Yongzheng Zhejiang tongzhi 浙江通志 [Local Gazetteer of Zhejiang Province]. Beijing: Beijing tushuguan chubanshe.

Jia, Sixie 賈思勰 (1982). Qimin yaoshu jiaoshi 齊民要術校釋 [Annotated Edition of the Qimin yaoshu]. Ed. by Qiyu 繆啟愉 Miao. Beijing: Nongye chubanshe.

Kuhn, Dieter (1988). Textile Technology: Spinning and Reeling. In: Science and Civilisation in China: Vol. 5. Ed. by Joseph Needham. Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 9. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Li, Bozhong 李伯重 (2002). Fazhan yu zhiyue: Ming Qing Jiangnan shengchan li yanjiu 發展與制約: 明清江南生產力研究 [Development and Constraint: A Study of Productivity in Ming-Qing Jiangnan]. Taipei: Lianjing.

– (2009). Tangdai Jiangnan nongye de fazhan 唐代江南農業的發展 [Agricultural Development in the Yangzi Delta during the Tang Dynasty]. Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe.

Li, Fang 李昉 (1960). Gujin zhu 古今注 (Commentary on Ancient and Modern Texts). In: Taiping yulan 太平預覽. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 3643 (juan 819, bubo bu liu, xu 3b).

Li, Qun 李群 and Bao Yanjie 包艷傑 (2010). Husang suoyuan 湖桑溯源 [The Origins of Husang]. Gujin nongye (1):82–8.

Liang, Jiabin 梁嘉彬 (1999). Guangdong shisanhang kao 廣東十三行考 [Study of the Guangdong Thirteen Firms]. Guangzhou: Guangdong renmin chubanshe.

Lin, Yongkuan 林永匡 and Wang Xi 王熹 (1985). Qianlong shiqi neidi yu Xinjiang Hasake de maoyi 乾隆時期內地與新疆哈薩克的貿易 [Trade between the Mainland and Xinjiang Kazakh during the Qianlong Period]. Lishi dang’an (4):83–8.

Liu, Zuxian 劉祖憲 (1964). Daoguang Anping xianzhi 道光安平縣志 [Local Gazetteer of Anping District (Daoguang Era)]. Guiyang: Guizhou renmin chubanshe.

– (1995). Xiangjian tushuo 橡繭圖說 [Illustrated Explanation on Oak Cocoons]. In: Xuxiu sikuquanshu 續修四庫全書. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

Luo, Wensi 羅文思 (1758). Xu Shangzhou zhi 續商州志 [Local Gazetteer of Shangzhou].

Ma, Zuchang 馬祖常 (1968). Ti Guangshan Xian Kongzai Binfengting 題光山縣孔宰豳風亭 [Inscription of the Pavilion Custom of Ancient Shaanxi of the Magistrate of the District Guangshan, in Actual Henan Province]. In: Yuan Wenlei 元文類. Ed. by Su Tianjue 蘇天爵. Taipei: Taiwan shangwu yinshuguan.

Mau, Chuan-hui 毛傳慧 (2010). Song Yuan shiqi cansang jishu de fazhan yu shehui bianqian 宋元時期蠶桑技術的發展與社會變遷 [The Development and Social Changes of Sericulture Technology in the Song and Yuan Dynasties]. In: Zhongguoshi xinun – keji yu Zhongguo shehui fence 中國史新論 – 科技與中國社會分冊 [New Perspectives on Chinese History: Science, Technology, and Chinese Society]. Ed. by Chu Ping-yi 祝平一. Taipei: Academia Sinica/Lianjing, 299–351.

– (2012). A Preliminary Study of the Changes in Textile Production under the Influence of Eurasian Exchanges during the Song-Yuan Period. Crossroads. Studies on the History of Exchange Relations in the East Asian World (6):145–204.

– (2018). Qing Local Officials and the Circulation of Wild Silkworms Rearing. In: Human Mobility and the Spatial Dynamics of Knowledge (XVIe–XXe si ècles). Ed. by Catherine Jami. Paris: Éditions IHEC, 61–99.

Mo, Shangjian 莫尚簡 and Zhang Yue 張嶽 (1963). Jiajing Hui’an xianzhi 嘉靖惠安縣志 [Local Gazetteer of Hui’an]. In: Tianyige cang Mingdai fangzhi xuankan 天一閣藏明代方志選刊 [A Collection of Local Gazetteers of Ming Dynasty in Tianyige]. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

Morse, Hosea Ballou (1926–1929). The Chronicles of the East India Company Trading to China 1635–1834. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ni, Qiwang 倪企望 and Zhong Tingying 鐘庭英 (1976). Jiaqing Changshan xianzhi 嘉慶長山縣志 [Local Gazetteers of Changshan]. Taipei: Chengwen chubanshe.

Peigler, Richard S. (1992). Wild Silks of the World. American Entomologist 39(3): 151–162.

Qianlong 24 nian Yingjili tongshang an 乾隆二十四年英吉利通商案 [The English Trade Case in the Year of Qianlong 24] (1963). Shiliao xunkan (3 and 5).

Qiu, Guangming 丘光明 (1992). Zhongguo lidai duliangheng kao 中國歷代度量衡考 [A Study of the Historical Weights and Measures in China]. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe.

Quan, Hansheng 全漢昇 (1991). Song Ming jian baiyin goumaili de biandong jiqi yuanyin 宋明間白銀購買力的變動及其研究 [The Development of the Purchasing Power of Silver between Song and Ming Dynasties and Its Research]. In: Zhongguo jingjishi yanjiu 中國經濟史研究 [A Study of Chinese Economic History]. Taipei: Daoxiang chubanshe, 580–84.

Rowe, William T. (2002). Saving the World: Chen Hongmou and Elite Consciousness in Eighteenth-Century China. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Schottenhammer, Angela (1999). Local Political-Economic Particulars of the Quanzhou Region During the Tenth Century. Journal of Song Yuan Studies (29):1–41.

Shen, Lian 沈練 (1995). Guang can sang shuo jibu 廣蠶桑說輯補 [A Supplement of the Collected Articles on Sericulture]. In: Xuxiu sikuquanshu 續修四庫全書. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

Shen, shi 沈氏 (1966). Shenshi nongshu 沈氏農書 [Mr. Shen’s Book of Agriculture]. In: Baibu congshu jicheng. Taipei: Yiwen yinshuguan.

Shi, Xiu 施宿 (1983). Jiatai Kuaiji zhi 嘉泰會稽志 [Local Monograph of Kuaiji (Jiatai Era)]. In: Zhongguo fangzhi Congshu 中國方志叢書 [China Local Gazetteers]. Taipei: Chengwen chubanshe.

Sinongsi, 司農司 (1995). Nong sang jiyao 農桑輯要 [Essential Compilation of the Agriculture and Sericulture]. In: Xuxiu sikuquanshu 續修四庫全書. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

Song, Xixiang 宋希庠 (1947). Zhongguo lidai quannongkao 中國歷代勸農考 [An Introduction to Agriculture Encouragement History in China]. Shanghai: Zhengzhong shuju.

Sun, Tingquan 孫廷銓 (1983). Shancan shuo 山蠶說 [On Mountain Silkworms]. In: Yanshan zaji 顏山雜記 [Essays of Yanshan], Yingyin wenyuange siku quanshu 景印文淵閣四庫全書. Taipei: Taiwan shangwu yinshuguan.

Tuojin 托津 (1991). Qinding Da Qing huidian shili (Jiaqing chao) 钦定大清会典事例 (嘉慶朝) [Imperially Commissioned Collection Regulations and Precedents of the Qing Dynasty (Jiaqing)]. Taipei: Wenhai chubanshe.

Wang, Shimao 王世懋 (1995a). Minbu Shu 閩部疏 [Commentaries on Min]. In: Xuxiu sikuquanshu 續修四庫全書. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

Wang, Shizhen 王世偵 (1997). Yuyang shanren wenlue 漁洋山人文略 [Essays of Yuyan shanren]. In: Siku quanshu cunmu congshu 四庫全書存目叢書. Ji’nan: Qilu shushe.

Wang, Xianqian 王先謙 (1963). Donghua xulu 東華續錄 [Sequel to the Donghua Records]. In: Shi’er chao Donghua lu 十二朝東華錄 [Donghua Records of the Twelve Reigns]. Taipei: Wenhai chubanshe.

Wang, Yuanting 王元綎 (1905). 野蚕录 [Record of Wild Silkworms]. 4 vols. Shanghai: Shangwu yin shuguan.

– (1995b). Shancan shuolue 山蠶說略 [A Brief Record of Silkworms]. In: Xuxiu sikuquanshu 續修四庫全書. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

Wang, Yuhu 王毓瑚 (2006). Zhongguo nongxue shulu 中國農學書錄 [A Record of Treatises on Agriculture in China]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju.

Wang, Zhen 王禎 (1981). Wangzhen nongshu 王禎農書 [Wang Zhen’s Book of Agriculture]. Beijing: Nongye chubanshe.

Wang, Zhideng 王穉登 (1971). Keyue zhi 客越志 [Records of travel to Yue]. In: Congshu jicheng sanbian. Taipei: Yiwen yinshuguan.

Wei, Chang 衛萇 (2004). Qianlong Qixia xianzhi 棲霞縣志 [Gazetteer of Qixia District]. In: Zhongguo difangzhi jicheng 中國地方志集成 [A Collection of Chinese Gazetteers]. Nanjing: Fenghuang chubanshe.

Wei, Yuan 魏源 and He Changling 贺长龄, eds. (1992). Qing jingshi wenbian 清經世文編 [Collected Writings on Statecraft of Qing Dynasty]. Beijing: Zhonghua chushushe.

Wu, Chengluo 吳承洛 (1984). Zhongguo du liang heng shi 中國度量衡史 [A History of Chinese Metrology]. Shanghai: Shanghai shudian.

Wu, Xuan 吴烜 (1995). Zhong sang shuo 種桑說 [On Planting Mulberry Trees]. In: Xuxiu sikuquanshu 續修四庫全書. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

Xiao, Guan 蕭琯 (1852). Daoguang Guiyang fuzhi 道光貴陽府志 [Local Gazetteer of Guiyang Prefecture (Daoguang Era)].

Xu, Chengdong 徐成棟 (1755). Lianzhou fuzhi 廉州府志 [Local Gazetteer of Lianyhou Prefecture]. Guangxi.

Yan, Shukai 嚴書開 (1995). Yan Yishan xiansheng wenji 嚴逸山先生文集 [A Collection of Mr. Yan Yishan]. In: Siku jinhuishu congkan 四庫禁毁書叢刊, Jibu 90. Beijing: Beijing chubanshe.

Yang, Shen 楊屾 (1995). Binfeng guangyi 豳風廣義 [Extensive Explication of Shaanxi Customs]. In: Xuxiu sikuquanshu 續修四庫全書. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

Yang, Siqian 陽思謙 (1987). Wanli Chongxiu Quanzhou fuzhi 萬曆重修泉州府志 [Local Gazetteer of Quanzhou (Wanli Era)]. In: Zhongguo shixue congshu sanbian 中國史學叢書三編 [Compendium of Chinese Historical Studies, No. 3]. Taipei: Taiwan xuesheng shuju.

Yi, Xing 易行 and Sun Jiazhen 孫嘉鎮, eds. (2005). Ming Taizu shilu 明太祖實錄 [Veritable Records of Emperor Taizu (1368–1398)]. In: Chaoben Ming shilu 鈔本 明實錄 [Veritable Records of the Ming Dynasty, handwritten copy]. Beijing: Xianzhuang shuju.

Yu, Wei 俞渭 and Chen Yu 陳瑜 (2006). Liping fuzhi 黎平府志 [Local Gazetteer of Liping]. In: Zhongguo difangzhi jicheng 中國地方志集成 [A Collection of Chinese Gazetteers]. Chengdu: Bashu shushe.

Zhang, Kai 章楷 (1992). Zhongguo gudai zaisang jishu shiliao yanjiu 中國古代栽桑技術史料研究 [Study of Ancient Chinese Technologies of Planting Mulberry Trees]. Beijing: Nongye chubanshe.

Zhang, Tingyu 張廷玉 (1997). Mingshi 明史 [History of Ming Dynasty]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju.

Zhao, Erxun 趙爾巽 (1977). Qing shi gao 清史稿 [The Draft History of Qing]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju.

Zhao, Jishi 趙吉士 (1991). Jiyuan jisuo ji 寄園寄所寄 [Transmissions from the Adobe of Mr. Jiyuan]. In: Zhongguo biji xiaoshuo wenku 中國筆記小說文庫 [Collection of Chinese Novels and Jottings]. Shanghai: Shanghai wenyi chubanshe.

Zheng, Zhen 鄭珍 (1995). Chu jian pu 樗繭譜 [Manual on Ailanthus Silkworms]. In: Xuxiu sikuquanshu 續修四庫全書. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

Zhongguo nongye yichan yanjiushi, 中国农业遗产研究室 (1984). Zhongguo nongxue shi (xia) 中國農學史 (下) [A History of Chinese Agriculture, Part II]. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe.

Zou, Hanxun 鄒漢勛 (2004). Anshun fuzhi 安順府志 [Gazetteer of the Prefecture Anshun in Guizhou]. In: Zhongguo difangzhi jicheng 中國地方志集成 [A Collection of Chinese Gazetteers]. Nanjing: Fenghuang chubanshe.

Footnotes

Tuojin 托津 1991, 7170–71 (juan 900, Gongbu, “Neiwufu 16,” 11b–12a) lists silk prices regulated by the central authority for raw material acquisition for the Imperial Weaving Manufactures according to different uses, including imperial families, tributary nobles and administrations. A margin was tolerated for adapting to market movements.

In his work on Textile Technology, Dieter Kuhn dealt with Chinese traditional production of textile fibres (hemp, ramie, cotton, and silk), but did not mention the artisanal industry of wild silk. Kuhn 1988.

Li 1960. 1 dan equalled 100 sheng; 1 sheng was equivalent to 0,342 ml. Cf. Wu 1984, 70.

In regions such as Bengal, wild silk, tussah, represented an important industry. See Peigler 1992.

“Unwind Silk from Wild Cocoons by Appreciating Its Low Price

(

Sinongsi 1995, 124–25 (juan 4, 5b–6b). One can read

the method for using bean flour after the third moulting on

pages 14a–b (129) of the same juan (Damian taisi

Sinongsi 1995, 134 (juan 4, 24b).

See Jia 1982, 231–32.

Chen 1966 juan shang, 8a-9b, “fentian zhiyi pian

Up to the introduction of French sericultural knowledge in the late nineteenth century, Chinese farmers grew silkworms in their own home. When sericulture season came round, farming families fitted out a room for the silkworms to stay in.

Ma

Cf. Song 1947, 66.

Zhao 1991, “Shiduji

Several sources bemoan the high tax load. In 1425, for

instance, the prefecture of Suzhou owed eight million dan of tax. Owing to the efforts of Zhou Chen

Jia 1982, juan 5, “Zhong sang zhe di 45”: “

See for example Shen 1995, juan shang, 5a–7b.

The Local Monograph of Kuaiji

Huang 1966. In the handbooks which appeared later than Canjing, such as Can sang

jiyao by Shen Bingcheng

Wu 1995, 7a–b, 279. As for Lu Xiechen

In addition to the example mentioned above, one can find

several similar cases: Fang 1986, liezhuan di 41, zhi di 19 mentioned: “in the seventh year of Taikang era (AD

286), the cocoons formed by wild silkworms at Donglai Mountain

reached forty li (ca. 4,5 km) and the

indigenous peoples collected them for reeling silk and making

goods.” (

The term “official list of textile production encouragement” is used in a figurative sense; When provincial or local officials encouraged textile cultures, many of them encouraged wild silk culture at the same time with domesticated sericulture.

For example, the Gazetteer of Qixia

District (Qixia xianzhi

“

Wang 1963, juan 6, 15b–16a, “Qianlong chao,” 203b–204a. So far I have been unable to locate the original of this booklet. However, after the distribution of the first edition by Qianlong, many local officials included either unabridged text or extracts in their local gazetteers, such as the whole text reproduced in Xu 1755 and the extracts in Luo 1758.

For more details on the biography and career of Chen Hongmou, see Rowe 2002. Chen 1995, vol. 978, 647.

Hada 1970, juan 10, “Canshi

For more details on Aertai, Zhao 1977, 10875–878 (juan 326, “liezhuan 113”).

Chen 2004, juan 37,

1152. According to Yang Hongjiang

“

In 1755, several merchants from different European Indian

companies were busy opening up ports for maritime trade. This

led to the imprisonment in 1759 of James Flint—an agent of the

British East India Company. One can gather details of the affair

through numerous documents in English, Chinese and other

languages. Some of China’s trade affairs with the British were

published in Shiliao xunkan

For statistics on the silk trade in Xinjiang, see Lin and Wang Xi 王熹 1985; Fan and Wen Jin 金文 1993, 301–48.

The text on “Zhong Xiang” is held in

Zou 2004, juan 53, Yiwen zhi 10 and the proclamation (qing

zhongxiang yucan zhuang) in Gu 2004, juan 33, xianzheng zhi, 11a–b. Wei Yuan

Liu 1995, vol. 978, 551. See also Liu 1964, juan 4 “Tuchan

Yu and Chen Yu 陳瑜 2006, vols. 17–18, juan 3 xia, 49 a–b. Wang Yuanting reproduced the passage in Wang 1995b, vol. 978, 651–52.