There is no linguistic evidence for the presence of any kind of multilingualism in China

The historical period begins very late in China in comparison with Egypt and the Ancient Near East, by a measure of close to two millennia. The earliest known texts written in Chinese date from about 1200 BCE, and for the next thousand or more years, there is nothing known from the Chinese world written in any language other than Chinese. We might admire the pre-eminence of the sinitic cultural hegemony

Mencius 3A.4

吾聞用夏變夷者, 未聞變於夷者也. [...] 南蠻鴃舌之人非先王之道. [...] 吾聞出於幽谷遷于喬木者, 未聞下喬木而入于幽谷者.4

I have heard of taking advantage of Chinese culture to transform the “backward,” but I have never yet heard of being transformed into the “backward.” [...] The shrike-tongued people of the southern backwaters repudiate the proper ways of the former kings. [...] I have heard of emerging out of a dark valley to perch in a stately tree; but I have never yet heard of descending from a stately tree to enter into a dark valley.

From the evidence of this passage we can see that for Mencius the distinction between “Chinese” and “non-Chinese” is entirely cultural, and the “shrike-tongued” people

The nature of the evidence changes markedly about a hundred and fifty years later, during the Western Han dynasty

The presumed purpose of Zhang Qian’s mission was to forge an alliance with the Yuezhi against the people known as the Xiongnu

Exactly why the Han court was so eager to involve itself in the contentious relations of non-Chinese people on the northwest frontier, hoping to join with the Yuezhi in an offensive against the Xiongnu, is never made very clear by the Chinese sources. The usual explanation starts from a presumption that the Xiongnu were horse-riding, marauding barbarian

The real reason for the Han court’s

As it happened, the Han court was unsuccessful in its efforts to establish an alliance with the Yuezhi. The historical record says that on his way to make contact with the defeated Yuezhi people, Zhang Qian was captured by the Xiongnu, detained for a decade, given a Xiongnu wife and produced a number of Sino-Xiongnu offspring before he managed to escape and proceed in his quest to meet up with the Yuezhi. The Chinese histories are careful to mention that through all of this Zhang Qian never lost possession of his Han court credentials, inter alia reminding us of the importance of the Chinese / “barbarian” distinction. When Zhang Qian finally made contact with the Yuezhi, it was some two or three thousand li further west than he expected, in the area between the lower reaches of the Jaxartes

大月氏在大宛西可二三千里. 居媯水北. 其南則大夏, 西則安息, 北則康居. [...] 故時彊. 輕匈奴. 及冒頓立攻破月氏. 至匈奴老上單于殺月氏王以其頭為飲器. 始月氏居敦煌祁連間. 及為匈奴所敗乃遠去. 過 宛西擊大夏而臣之. 遂都媯水北為王庭. 其餘小眾不能去者保南山羌. 號小月支.

The Great Yuezhi were located to the west of Da-yuan (*ddah-ʔwanʔ= Tocharia) perhaps two or three thousand li. They dwelt north of the Gui (Oxus) river. To their south was Da-xia (Bactria), to their west was An-xi (*ʔʔan-sək= Arsacids, i.e., the Parthians) and to their north was Kang-ju (* kkhaŋ-ka) [...] In former times they were strong and treated the Xiongnu dismissively. When Mao-dun was established [as the Xiongnu chieftain] he attacked and smashed the Yuezhi. Later the Xiongnu senior elder Chan-yu killed the Yuezhi king and made his head into a drinking vessel. Before that the Yuezhi had lived in the area between Dun-huang and Qi-lian. It was only when they came to suffer defeat at the hands of the Xiongnu that they moved far away. They passed to the west of [Da-]yuan and attacked Da-xia (Bactria), which state they then subjugated. They then located their royal court to the north of the Gui (Oxus) river. A small number of them remained behind and took refuge in the areas of Nan-shan and Qiang-zhong. These were called the Lesser Yue-zhi.

This part of the Chinese historical record is notable because the defeat of Bactria by the Yuezhi

The official Chinese histories, chiefly the Shiji and the Hanshu

Expressed thusly, the Chinese historiographical record bespeaks, from the traditional Chinese perspective, a considerable cultural disdain for the Xiongnu. The picture is drawn in a way that highlights the great differences in cultural conventions and standards between the Xiongnu and the Chinese, and it is presented exclusively from a Sino-centric point of view. As with the Mencius

Apart from religious texts that accompanied the introduction of Buddhism from India

About a century after the compilation of the Hou Han shu

Gaoseng zhuan chap. 9:

[佛圖] 澄曰

相輪鈴音云「秀支替戾岡, 僕谷劬禿當」. 此羯語也. 秀支軍也. 替戾岡出也. 僕谷劉曜胡位也. 劬禿當捉也. 此言軍出捉得曜也.

Fo-tu Deng 佛圖澄 said [to Shi Le]:

The sounds of the transmigration wheel hand-bells say to me “/suw-tɕi thεj-lεj-kang bəwk-kəwk guə-thəwk-tang/.” This is the Jie (EMC kät = Ket?) language.

秀支 /suw-tɕi/ means ‘army’

替戾岡 /thεj-lεj-kang/ means ‘to come forth’

僕谷 /bəwk-kəwk/ means ‘the “barbarian” seat of Liu Yao’

劬禿當 /guə-thəwk-tang/ means ‘to capture’

Thus, this line means “The army will come forth and capture Liu Yao.”

Fo-tu Deng’s comment is clearly intended to suggest that these sounds, emanating from a kind of Buddhist hand-bell and said to resemble the Jie language, predict a victory for Shi Le over his adversary, Liu Yao, and indeed Shi Le won just such a victory in 328 and executed Liu Yao in 329. Here again the passage is more interesting historically than it is useful linguistically. If the passage does indeed represent in some approximate way one or more sentences in a real (non-Chinese) language, and if the individual word-for-word glosses

The ten-word foreign-language passage is usually referred to as the “Xiongnu couplet,”kkhaŋ-ka, that occurs frequently in earlier, Han period, texts. Kang-ju

How these data fit together to reveal unambiguously the linguistic identity of Shi Le is difficult to say. The historical record says that he was a Xiongnu, the language of the Gaoseng zhuan and Jin shu passages suggest, tenuously at best, that he was Kets-rak-, the first syllable of the name Luoyang 洛陽.25 Shi Le

The moral of this story, as far as multilingualism in early China is concerned, is that names such as Xiongnu in the Chinese written historical record, and perhaps xwn in the Sogdian

The same near silence that we find in early written Chinese records about non-Chinese languages extends also to non-Chinese orthographies. To be sure, there is no clear evidence of writing of any kind other than Chinese in China prior to the advent of Buddhism in the early second century CE, so there may well have been nothing for the Chinese to have noticed in this regard at such an early period. In fact the historical records describing those various frontier groups with whom the Han court

Accompanying the arrival of Buddhist missionaries

Thanks to the predominance of Sogdian

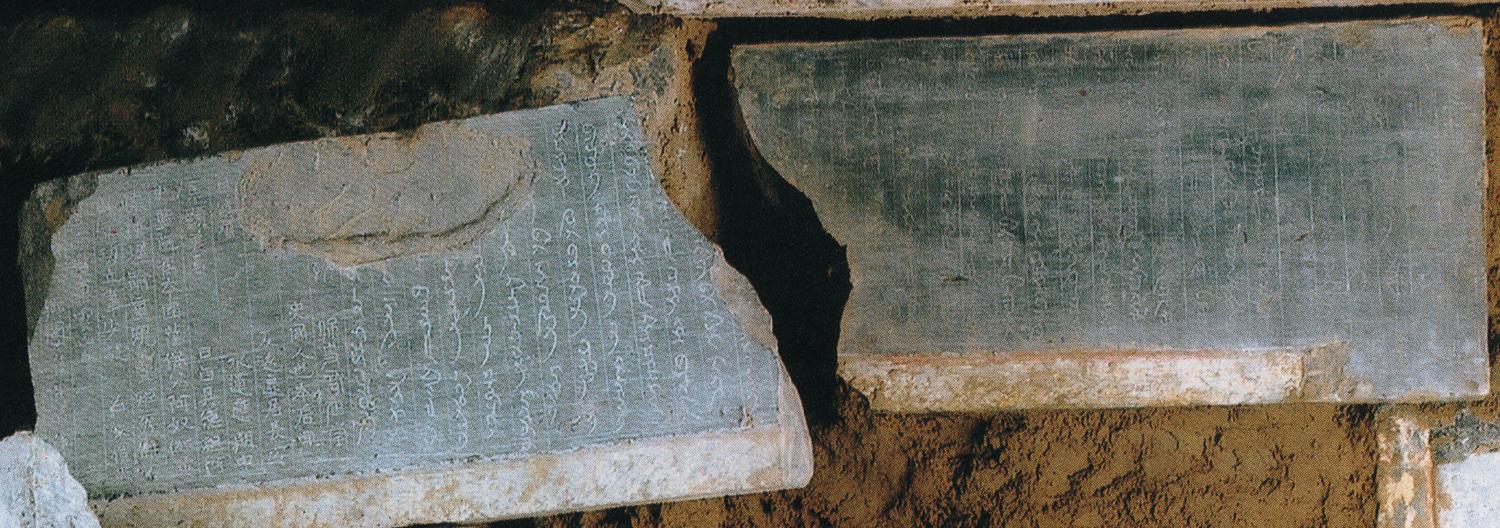

Fig. 15.1: The tomb of Sogdian sabao Wirkak (Archaeological Bureau of Xi’an for the Preservation of Cultural Relics 2005).

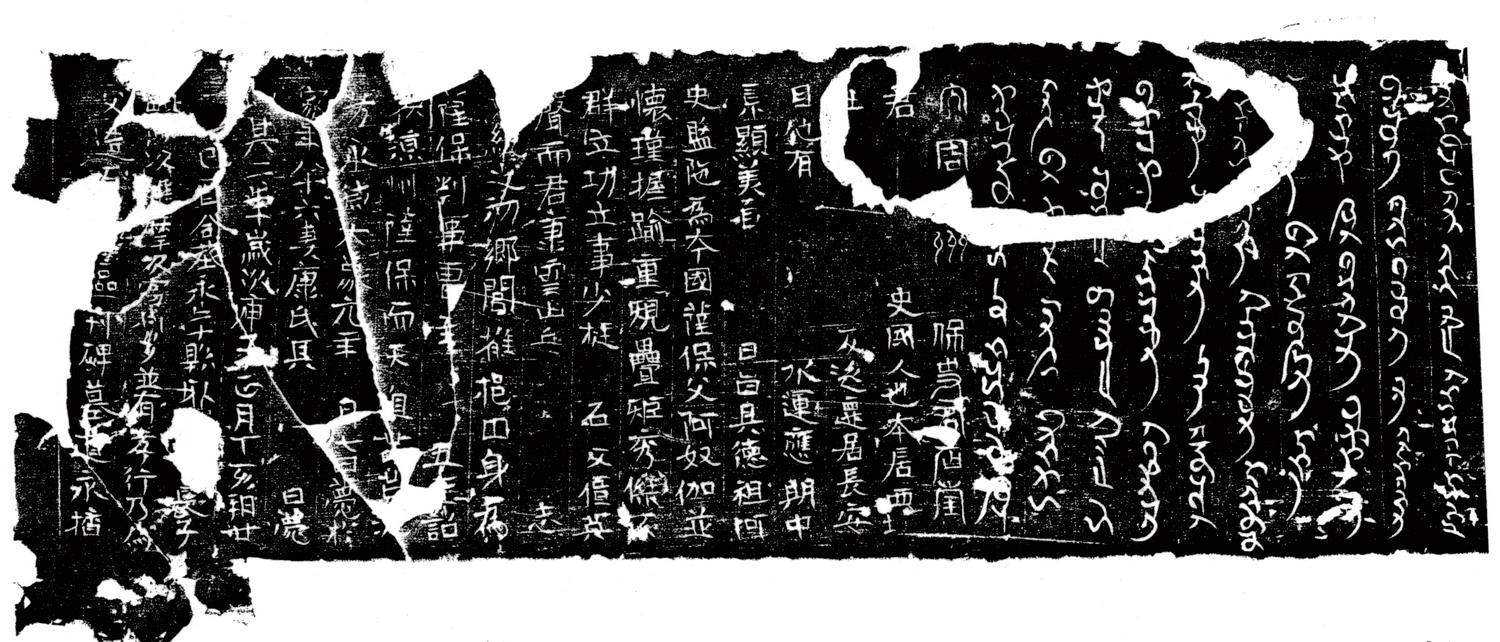

Fig. 15.2: Wirkak tomb, Chinese and Sogdian bilingual lintel inscription (Archaeological Bureau of Xi’an for the Preservation of Cultural Relics 2005).

Fig. 15.3: Rubbing of a part of the lintel inscription. (Archaeological Bureau of Xi’an for the Preservation of Cultural Relics 2005).

Remarkably, the Sogdian script

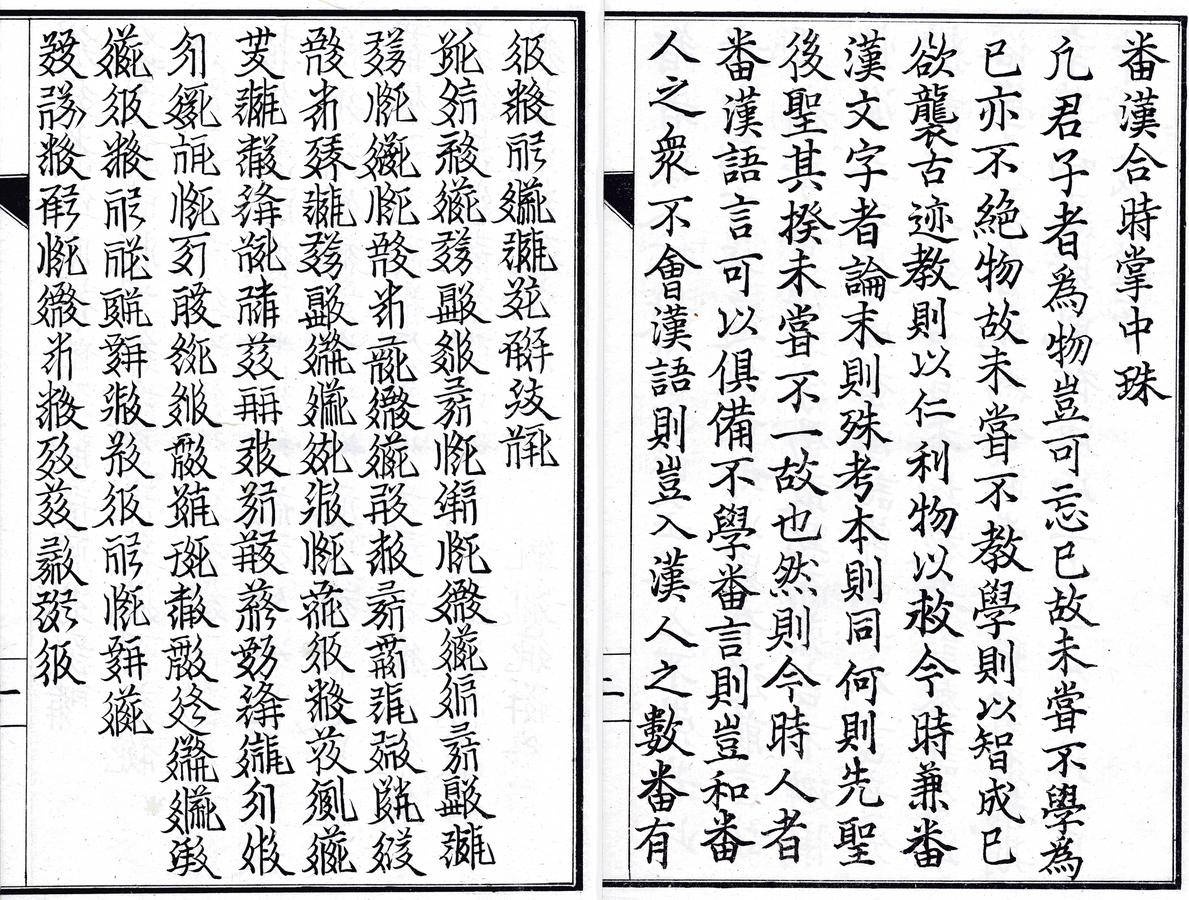

Fig. 15.4: Tangut, i.e., Xi Xia (left), and Chinese (right), preface to the Fan Han heshi zhangzhong zhu 番漢合時掌中珠. From the 1924 printing

The apparent disinterest on the part of the Chinese toward the languages, and especially the scripts, of the foreign people with whom they interacted

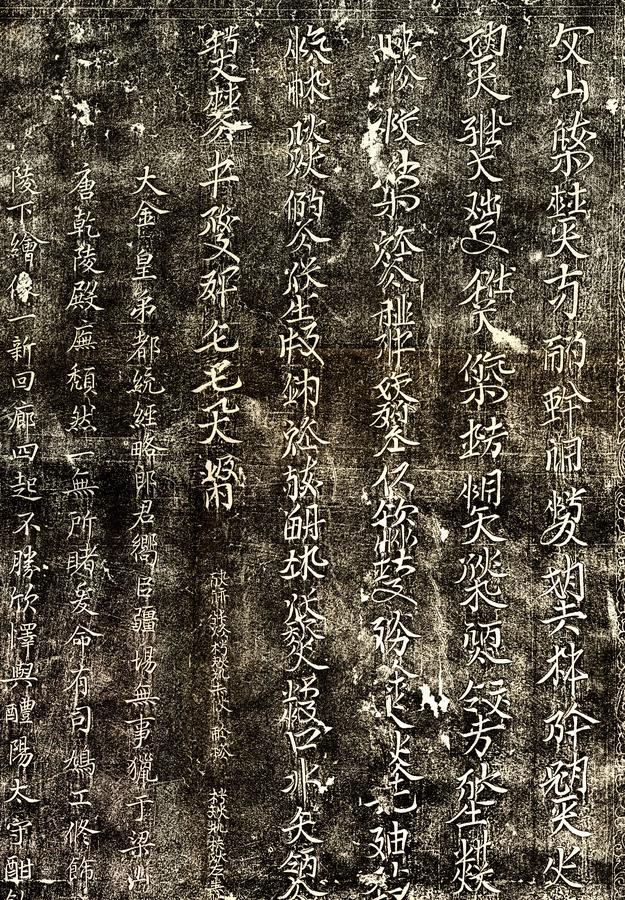

Fig. 15.5: Jurchen writing. Inscription on a bronze mirror, from (Bushell 1897, 21).

Fig. 15.6: Bilingual Chinese (small characters, left) - Khitan (large characters, right) epigraphic text. Second half of the eleventh century, rubbing (partial), from (Luo Zhenyu 羅振玉 1934, chap. 2, plate 20).

With the success of the Yuan / Mongol dynasty itself the picture changes once again. The Yuan

至元六年詔頒行於天下. 詔曰朕惟字以書言. 言以紀事. 此古今之通制. 我國家肇基朔方. 俗尚簡古. 未遑制作. 凡施用文字因用漢楷及畏吾字以達本朝之言. 考諸遼金以及遐方諸國. 例各有字. 今文治寖興而字書有闕. 於一代制度寔為未備. 故特命國師八思巴創為 蒙古新字. 譯寫一切文字. 期於順言達事而已. 自今以往凡有璽書頒降者並用蒙古新字. 仍各以其國字副之.

In the sixth year of the Ultimate Origin reign period (of Qubilai Qagan, = CE 1269) an imperial edict was distributed throughout the Subcelestial Realm. The edict said:

We aver that —

By means of characters we write words and by means of words we record matters. This has been the ubiquitous practice from antiquity to the present. Our State finds its first foundation in the Far North. Our customs remain still simple and old-fashioned. We have never had the leisure to devise or create [anything new.] In general when we made use of writing we relied on using the “square-shaped” characters of the Han or the script of the Uighurs in order to express the statements of the Present Court. If we look at this in connection with the Liao (Khitan) state, or the Jin (Jurchen) state, or any of the still remoter states, the fact is that each has its own script. For us, literacy and administrative order both have gradually come to be fully developed, yet as far as having documents written in our own script, here we are still wanting. For the practices and institutions of our particular era, this is the thing that has still not been made available.

Therefore–

We especially command the State Preceptor, [the] ‘Phags-pa[Lama], to devise a new Mongol Script, to accommodate the transcription of all other writing systems [of the empire]. We look simply to reflect our language fluently and register our affairs effectively. From this time on in general all documents bearing the imperial seal that are handed down for distribution will use this new Mongol Script , at the same time maintaining the script of the state in question alongside as a supplement to it.39

Specifically, the assignment was given to a Tibetan Lama, usually referred to as the ‘Phags-pa Lama

Whatever ancillary influences may have been in play, the ‘Phags-pa script is clearly based chiefly on Classical Tibetan, a horizontally written abugida-type of writing

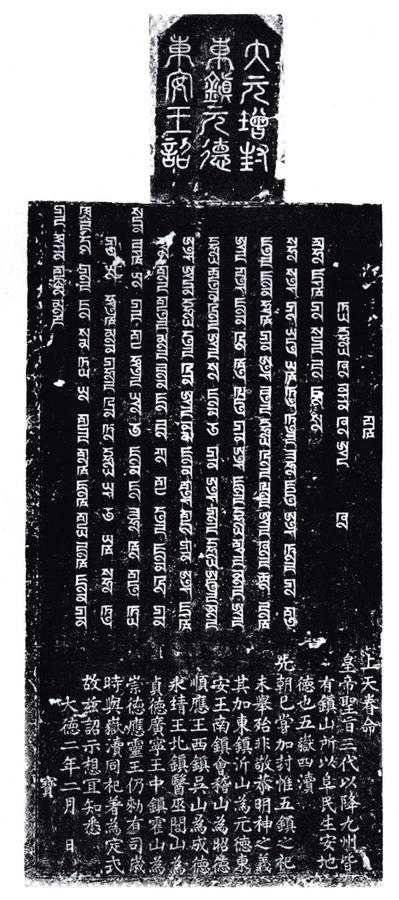

Fig. 15.7: Bilingual Chinese (seal script top, standard script bottom)—‘Phags-pa (middle) stele inscription, dated 1298. From Luo Changpei 羅常培 and Cai Meibiao 蔡美彪 (2004).

The ‘Phags-pa script was intended to be widely used throughout the Mongol empire for all kinds of administrative, literary, ceremonial and practical purposes, but that intention seems not to have been entirely realized. The script is known in large part from extant monumental and epigraphic uses from the Mongol period (Figure 15.7).

Most recently the ‘Phags-pa script

Fig. 15.8: Mongolian Academy of Sciences Silk Banner, seven varieties of traditional Mongolian script; ‘Phags-pa (right-most vertical script). From ECHO Cultural Heritage Online (http://echo.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/content/buddhism/mongolscript), accessed April 7, 2017. All seven Mongol script varieties simply transcribe the name “Max Planck Society.”

With the fall of the Mongol dynasty political control over China came into the hands of the indigenous Chinese ruling house of Zhu 朱, founders of the Ming

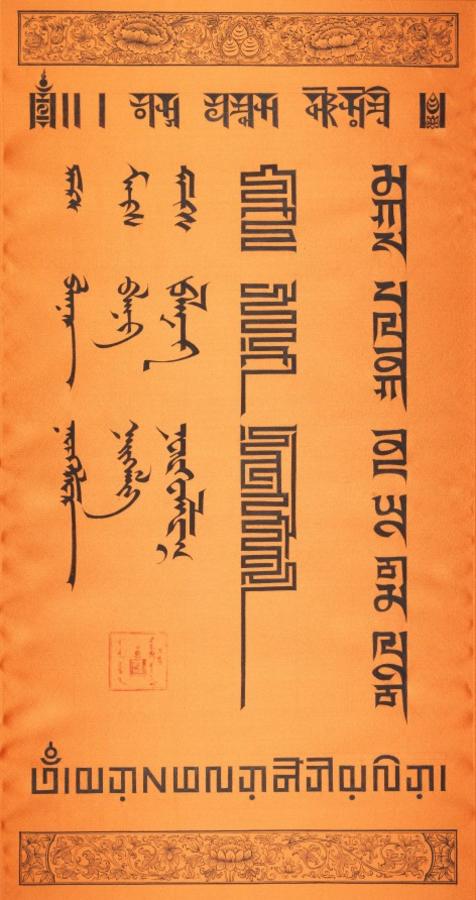

Fig. 15.9: Title page of the Yu zhi wu ti Qing wen jian 御製五體清文鑑. The left-most title is Manchu, Hani araha sunja hačin hergen kamciha Manju gisuni buleku bithe; followed (left to right) by Tibetan, Mongolian and Uighur, with Chinese on the right-most. The full title can be rendered as Imperially Commissioned Mirror of the Five Languages of the Manchu / Qing Dynasty.

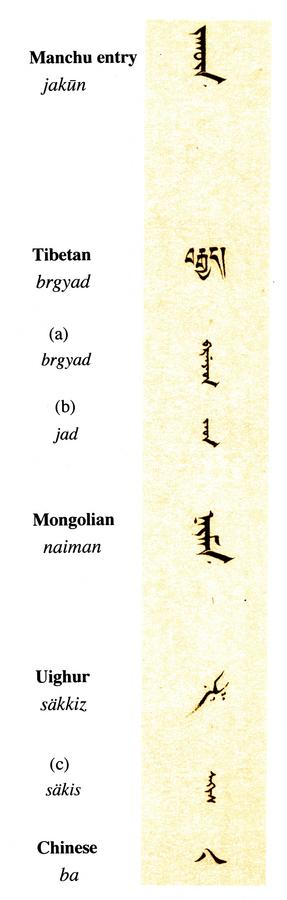

Fig. 15.10: The entry for “eight” in the Yu zhi wu ti Qing wen jian (p.0841).

Only with the demise of the Ming

One of the most remarkable of the linguistic and orthographic features of this dictionary is the fact that for every Tibetan

The top item is the Manchu entry jakūn “eight” and the bottom is the Chinese. The second from the top is the Tibetan word for ‘eight,’ viz., brgyad, followed by two smaller size Manchu entries. The first of these, (a) in Figure 15.10, is brgyad, written in the standard Manchu script, representing the Tibetan orthography

Wolfgang Behr, writing about the history of linguistic and translation

Looking at the development of translation and interpretation as reflected in non-Buddhist Ancient and Mediaeval Chinese texts, the most striking observation to be made is the enormous paucity of available evidence and references. It is painfully obvious that throughout most of China’s pre-Qinghistory, there was a deeply engrained lack of interest in foreign languages [...]. (Behr 2010, 201)

Precisely the same thing can be said about the Chinese interest in foreign writing systems

Acknowledgements

A modest version of this paper was presented at the “Crossing Boundaries: Multilingualism, Lingua Franca and Lingua Sacra” TOPOI conference at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin in November 2010, where I benefitted greatly from comments and suggestions offered by the workshop participants and attendees. In preparing this fuller version I have been fortunate to have received very helpful advice, suggestions and corrections from Wolfgang Behr, Ian Chapman, Mårten Söderblom Saarela, Steve Wadley and the late Jerry Norman. For all of this I am very grateful; what remains wrong or confused (or both) is of course my own responsibility.

References

Archaeological Bureau of Xi’an for the Preservation of Cultural Relics (2005). “Xi’an bei Zhou Liangzhou sabao Shi jun mu fajue jianbao” 西安北周凍州薩保史君墓發掘簡報 (Brief Report of the Excavation of the Tomb of Master Shi, the sabao of Liang Prefecture of the Northern Zhou, at Xi’an). Wen wu 文物 3:4–33.

Behr, Wolfgang (2004). “To Translate” is “To Exchange” 譯者言易也 – Linguistic Diversity and the Terms for Translation in Ancient China. In: Mapping Meanings: the Field of New Learning in Late Qing China. Ed. by Michael Lackner and Natascha Vitinghoff. Leiden: Brill, 173–208.

– (2010). The Role of Language in Early Chinese Constructions of Ethnic Identity. Journal of Chinese Philosophy 30(4):567–87.

Brough, John (1961). A Kharosthī Inscription from China. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 24(3):517–30.

Bushell, S. W. (1897). Inscriptions in the Juchen and Allied Scripts. In: Actes du Onzième Congrès International des Orientalistes. 2. section: langues et archéologie de l’Extrême Orient. Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 11–35.

Coblin, W. South (1979). A New Study of the Pai-lang Songs. Tsing Hua Journal of Chinese Studies 12(1):179–216.

– (2007). A Handbook of ‘Phags-pa Chinese. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Daniels, Peter (1990). Fundamentals of Grammatology. Journal of the American Oriental Society 110(4):727–31.

Dien, Albert E. (2003). Observations Concerning the Tomb of Master Shi. Bulletin of the Asia Institute, n.s. 17:105–15.

Dunnell, Ruth (1994). The Hsi Hsia. In: The Cambridge History of China Vol. 6. Ed. by Denis Twitchett and Herbert Franke. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chap. 2, 154–214.

Eberhard, Wolfram (1952). Conquerors and Rulers, Social Forces in Medieval China. Leiden: Brill.

Gu gong bo wu yuan 故宮博物院 (1957). Yu zhi Wu ti Qing wen jian 御製五體清文鑑 (Imperially Commissioned Qing Pentaglot Dictionary). Beijing: Minzu.

Hao Shusheng 郝樹生 and Zhang Defang 張德芳, eds. (2009). Xuan-quan Han jian yanjiu 懸泉漢簡研究 (A Study of the Xuan-quan Han Wooden Slips). Lanzhou: Gansu wenhua.

Harrison, K. D. (2007). When Languages Die: The Extinction of the World’s Languages and the Erosion of Human Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Henning, W. B. (1938). Argi and the “Tocharians”. Bulletin of the School of Oriental (and African) Studies 9(3):545–71.

– (1948). The Date of the Ancient Sogdian Letters. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 12(3–4):601–15.

Hill, N. W. (forthcoming). Songs of the Bailang. Bulletin de l‘Ecole fran çaise d‘Extr ême-Orient.

Hu Pingsheng 胡平生 and Zhang Defang 張德芳, eds. (2001). Dun-huang Xuan-quan Han jian shi cui 敦煌懸泉漢簡釋粹 (Selected Notes on the Dun-huang Xuan-quan Han Wooden Slips). Shanghai: Shanghai guji.

Hyman, Malcolm (2006). Of Glyphs and Glottography. Language & Communication 26:231–49.

Kahane, Henry and Renée Kahane (1976). Lingua Franca: the Story of a Term. Romance Philology 1:25–41.

Ligeti, Louis (1950). Mots de civilisation de Haute Asie en transcription chinoise. Acta Orientalia Hungarica 1:141–88.

Lin Meicun (1991). A Kharosthī Inscription from Chang-an. In: Papers in Honour of Professor Dr. Ji Xianlin on the Occasion of his Eightieth Birthday. Ed. by Li Zheng and Jiang Zhongxin. Nanchang: Jiangxi Renmin, 119–31.

Luo Changpei and Cai Meibiao (2004). Basiba zi yu Yuan dai Han yu 八思巴字與元代漢語. Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue.

Luo Zhenyu 羅振玉 (1934). Liao ling shi ke ji lu 遼陵石刻集錄 (Collection of Stone Stele Inscriptions from Liao Dynasty Tombs). Fengtian: Fengtian Sheng gong shu.

Maenchen-Helfen, Otto (1948). History in Linguistics. Journal of the American Oriental Society 68(2):120–24.

– (1955). Pseudo-Huns. Central Asiatic Journal 1(2):101–6.

Norman, Jerry (2014). A Comprehensive Manchu-English Dictionary. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Ostler, N. (2010). The Last Lingua Franca: English until the Return of Babel. London: Harper Collins.

Pelliot, Paul (1927). “Šūl” ou Sarag? Journal Asiatique 211:138–41.

Pines, Yuri (2005). Beasts or Humans: Pre-imperial Origins of the ‘Sino-Barbarian’ Dichotomy. In: Mongols, Turks and Others: Eurasian Nomads and the Sedentary World. Ed. by Reuven Amitai and Michel Biran. Leiden: Brill, 59–102.

Poppe, Nicholas and John Krueger (1957). The Mongolian Monuments in HP’AGS-PA Script. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1963). The Consonantal System of Old Chinese, part II. Asia Major, n.s. 9(2):206–65.

– (1970). The Wu-sun and Sakas and the Yüeh-chih Migration. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 33(1):154–60.

– (1991). Lexicon of Reconstructed Pronunciation in Early Middle Chinese, Late Middle Chinese, and Early Mandarin. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Salomon, Richard (2007). Gāndhārī in the Worlds of India, Iran, and Central Asia. Bulletin of the Asia Institute, n.s. 21.

Shiratori, Kurakichi (1902). Über die Sprache des Hiung-nu Stammes und der Tung-hu Stämme. Bulletin de l’Academie Imperiale des Sciences de St-Petersbourg 5(2):1–33.

Sims-Williams, Nicholas (2005). Towards a New Edition of the Sogdian Ancient Letters: Ancient Letter 1. In: Les Sogdiens en Chine. Ed. by Étienne de la Vaissière and É. Trombert. Paris: École française d’Extrême-Orient, 181–93.

Söderblom Saarela, Mårten (2014). The Manchu Script and Information Management: Some Aspects of Qing China’s Great Encounter with Alphabetic Literacy. In: Rethinking East Asian Languages, Vernaculars, and Literacies, 1000–1919. Ed. by Benjamin Elman. Leiden: Brill, 169–197.

Sun Fuxi (2005). Investigations on the Chinese Version of the Sino-Sogdian Bilingual Inscription of the Tomb of Lord Shi. In: Les Sogdiens en Chine. Ed. by Étienne de la Vaissière and É. Trombert. Paris: École française d’Extrême-Orient.

Teggart, Frederick J. (1939). Rome and China. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Vaissière, Étienne de la (2005a). Huns et Xiongnu. Central Asiatic Journal 49(1): 3–26.

– (2005b). Sogdian Traders: A History. Ed. by trans. James Ward. Leiden: Brill.

Vovin, Alexander (2000). Did the Xiong-nu Speak a Yeniseian Language? Central Asiatic Journal 44(1):87–104.

Vovin, Alexander, Edward Vajda, and Étienne de la Vaissière (2016). Who Were the *kjet (羯) and What Language Did They Speak? Journal Asiatique 304(1):125–144.

Wild, Norman (1945). Materials for the Study of the Ssu Yi Kuan 四夷 (譯) 館 (Bureau of Tranlsators). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 11(3):617–40.

Wright, Arthur F. (1948). FO-T‘U-TENG 佛圖澄, A Biography. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 11:321–71.

Footnotes

For a precise linguistic history of the term lingua franca, see H. and R. Kahane (1976, 25–41). For a more recent, popular discussion of the term as it applies to English in the twenty-first century, with substantial historical background, see Ostler (2010).

The linguistically best-informed analytical survey of language contact in pre-imperial China is “The Role of Language in Early Chinese Constructions of Ethnic Identity” by Wolfgang Behr (2010). Behr observes at the outset of his paper that “early interactions with other languages” are “all but invisible in the early literature” Behr (2010, 568).

Wolfgang Behr, writing about linguistic and the matter of ‘translation’ in ancient China, says “direct or indirect references to the extraordinary linguistic diversity in Ancient China are surprisingly few” Behr (2004, 180). The linguistic diversity in ancient China can be called “extraordinary” not only because of the archaeologically and historically inferable presence of a multitude of different languages, but also because from transmitted Chinese historical records we know names and have summary descriptive accounts of people and states that are presumed to be non-Chinese, but we have, as Behr notes, precious little real linguistic data.

Extant transmitted versions show considerable variation between 于 and 於 in their multiple occurrences in this passage, two characters that are usually assumed to be allographs for the word yú “in relation to” by the time of the Mencius text.

Among the transcriptions that have been identified with the greatest (though perhaps still not quite complete) confidence are, for example, 樓欄 Lóu-lán < *krro-rran ‘Krorayina’ (Sogd. kr’wr’n), 于闐 Yú-tián < *gwa-ddin ‘Khotan’ (Khot. Hvatäna), 龜茲 Qiū-cí < *ku-dzə ‘Kucha’ (Toch. kuśī), 大宛 Dà-yuăn < **ddahʔwanʔ ‘Tocharia’ and 焉耆 Yān-qí < *ʔan-grij ‘Argi’ (Qarashahr, see Henning (1938, 570–71)). All of these names occur in transmitted Chinese historical texts representing the centuries just before and just after the beginning of the Common Era, though the texts themselves may in some cases have been compiled at somewhat later dates. The identifications given here have been proposed more than once in recent decades and most, if not all, are considered unproblematic, notwithstanding the inevitably imprecise and approximate nature of the proposed Old Chinese pronunciations. A large cache of Han period wooden slips dating from about 100 BCE to about 100 CE was found and excavated in 1990–92 in Xuan-quan 懸泉, a settlement on the trade route just east of Dunhuang 敦煌 in modern Gansu province. These wooden slips name two dozen non-Chinese locales of the “Western Regions,” presumably representing twenty-four distinct “countries” with whom the Han state had contact, including the five given here. By virtue of their early date these wooden-slip manuscript documents represent the earliest attested occurrence of virtually all of these names. I am grateful to Wolfgang Behr (University of Zürich) for drawing my attention to the Xuan-quan manuscript material and providing me with this preliminary information. In particular I have relied on his identifications and Old Chinese reconstructions for some (but not all) of the data for the five names given here. For introductory reports and studies of this discovery, see Hu Pingsheng and Zhang Defang (2001) and Hao Shusheng and Zhang Defang (2009).

Even when a Chinese name can be confidently matched linguistically with the name of a people known from a classical western source, we must be careful not to jump to the conclusion that this automatically tells us either the ethnic or the linguistic identity of the people in question. Names are easily transferred and impressionistically (mis-) applied in such circumstances, e.g., the English name “Gypsy” for a people who have no historical link to Egypt at all, or the indigenous people of the Americas called “Indians,” a name that became utterly conventional for half a millennium, long after it was clear that the name itself was a complete misnomer. For an explicit statement of the problem in the Central Asian context, see Maenchen-Helfen (1948).

Shiji 史記 123 (first c. BCE), Hanshu 漢書 61 (late second c. CE).

See Teggart (1939) for a detailed survey of the extent and importance of trade routes in the period between 58 BCE and CE 107 running between the Roman empire and the Han state. Anticipating his conclusions, Teggart writes in his Preface that “Within [the period 58 BCE to CE 107] every barbarian uprising in Europe followed the outbreak of war either on the eastern frontiers of the Roman empire or in the ‘Western Regions’ [i.e., the far northwest, modern Gansu and Xinjiang provinces] of the Chinese. Moreover, the correspondence in events was discovered to be so precise that, whereas wars in the Roman East were followed uniformly and always by outbreaks in the lower Danube and the Rhine, wars in the eastern T’ien Shan [i.e., Chinese Central Asia] were followed uniformly and always by outbreaks on the Danube between Vienna and Budapest.” (p. vii). To be sure, the Chinese could not have had any real knowledge of the Western extent of the trade routes, but this did not prevent them from indulging a considerable appetite for the luxury goods that reached them through these channels.

The corresponding account in the Hanshu (chap. 61) adds a line claiming that on their way west the Yuezhi had attacked the Sakas, causing the Sakas to flee to the south, and allowing the Yuezhi to occupy their land. Pulleyblank has shown that this is very likely a gratuitous detail added after the fact to the Hanshu’s later account of the Yuezhi migration west and their defeat of Bactria. Sakas are nowhere mentioned in any context in the earlier Shiji text, Pulleyblank (1970).

I am grateful to Ian Chapman (Seattle) for providing me a richly detailed and documented set of notes about recent historiographical and archaeological research on the demise of Graeco-Bactria.

Chinese attitudes toward “non-Chinese barbarians” is to be sure a complex and multifaceted subject and cannot be summarized in a single word. The point here has only to do with the consistent absence of any significant recognition of language differences as pertinent to the social or political world of early China. For a careful survey of the “Chinese and non-Chinese question” from all important perspectives, see Pines (2005).

See Coblin (1979) and Hill (forthcoming).

See Wright (1948). The fó-tú < EMC but-da part of this name is, of course, a transcription of buddha; what the dèng 澄 represents and how it should be read and understood is less clear. The character 澄 itself can be read either chéng < EMC dring or dèng < EMC dəngh. The Gaoseng zhuan biographical account of Fo-tu Deng says that the third character of his name was variously written as 蹬 dèng < EMC dəngh, 磴 or 橙, both dèng < EMC təngh, in addition to the 澄 that has become conventional. It goes on to say that however it was written, it was a transcription of the sounds of an Indic language (fan yin 梵音). These data, though admittedly inconclusive, suggest a preference for the reading dèng rather than chéng for the name, though the latter is the convention usually followed. Here and infra passim Early Middle Chinese reconstructions are taken largely unchanged from Pulleyblank (1991).

The passage is often called the “Xiongnu couplet” because of an unwarranted assumption that the language is “Xiongnu.” It is also found in the Jinshu chap. 95 biography of Fo-t’u Deng (Jinshu gouzhu 晉書斠注 95.24b). The Jinshu was compiled in the seventh century, about a hundred years later than the Gaoseng zhuan, and thus while contemporary studies usually cite the Jinshu text, the Gaoseng zhuan text is slightly earlier than the Jinshu text, though the uncertain textual histories of each make it difficult to know which is derivative of which. For this particular passage there are no textual variants between the two texts and therefore either can be used with confidence.

Pulleyblank (1963, 264–265).

Such a heterogeneous structure would be in keeping with the social and political organization of historically well-documented Central Asian Turkic and Mongol peoples from several centuries later. Even the names of some of these later groups suggest this kind of organization, e.g., the Toquz Oguz “Nine Oguz” (Turks), the Dörben Oiyrat “Four Oiyrat” (Mongols, i.e., the “Four Allies,” from Cl. Mong. oyir-a- ‘near to,’ possibly with -d [-t] as a plural suffix, “the nearby ones.” [I am grateful to the late Jerry Norman for details on the Mongolian etymology.]). The Mongolian historical chronicles call the Mongol nation by the term Tabun Önggetü “(People) of the Five Colors.” See Poppe and Krueger (1957, 3). For a discussion of this phenomenon from a sociological perspective, see Eberhard (1952, chap. 4: “Patterns of Nomadic Rule,” 65–88).

Pulleyblank (1963, 246–248). Vovin (2000, 91) points out that linguistic data not available to Pulleyblank in the early 1960s and recent work in reconstructing the history of the Yeniseian languages overall suggest that the name Jie < kät probably does not mean ‘stone,’ but is simply an ethnonym. Basing himself on data from G. Starostin, he allows that as an ethnonym it may be a descendant of Proto-Yeniseian *keʔt ‘person.’

Vaissière (2005b, 119).

Vaissière (2005b, 120) identifies seven Chinese surnames typically taken by Sogdians, each neatly associated with a particular regional origin. The surname Shi 石 in this scheme is matched with Sogdians specifically from the area of Čač. (Chinese shí < EMC dźiajk [“stone”] may in this context in fact have been a transcription of the Sogdian toponym Čač.) De la Vaissière then goes on to point out that it is very much an over-simplification to conclude that a given surname means that the person in question was a Sogdian from whatever place may have been typically identified with that surname. We know from the Chinese sources that Shi Le had the surname Shi, and that he was from Kang-ju, an area very near Čač, but even though these facts fit the neat “one surname - one regional origin” scheme, we cannot simply conclude on this basis alone that Shi Le was a Sogdian, though that possibility is not ruled out.

This attack is also mentioned in the second letter, where Yeh < *ŋap 鄴 is referred to by the Sogdian transcription ‘nkp,’ i.e., ŋapa. See Henning (1948, 609).

In an extensive discussion of the importance of the Sogdian “ancient letters” for establishing the historicity of a vast, well-organized Sogdian mercantile network stretching from the Aral Sea in the west into the heart of China in the east, Étienne de la Vaissière states that the second letter is “one of the essential documents for the history of the 4th century CE, because of the name it gives to the Xiongnu who sacked Luoyang, xwn, the Huns, sixty years before they swept across the borders of the Roman Empire [...]” Vaissière (2005b, 43). In a later, still more detailed examination of the sixty-year old debate over the Xiongnu / Hun equation, he says that in his view the conclusion that the fourth and fifth century Huns of Europe were in fact the Xiongnu of Chinese record of a few centuries earlier is inescapable. He claims that the Sogdian designation xwn is not a generic term for “barbarians,” but refers specifically and exclusively to the Xiongnu.

De la Vaissière shows, whatever the speculative nature of his conclusions, that the subject is both ethnolinguistically and historically complex. The second of the ancient letters, to be sure, seems clearly to attest to the fact that the hostile forces that destroyed Luoyang in 311, called Xiongnu in the Chinese historical records, are called xwn in the Sogdian epistolary account of the same historical event, a name that is essentially indistinguishable from the name that was applied by later western historians to the invaders who threatened the Roman east, plundering Adrianople, in the late fourth century and who ravaged the west in the fifth. While the letter thus establishes a nominal identity of the Xiongnu with the Huns, it all the same tells us little about who the Xiongnu actually were and what, if any, their historical relation with the Huns (still unknown in western sources this early) might have been. De la Vaissière assembles a great deal of textual, archaeological and linguistic data not available to scholars sixty years ago to claim that the case for the historical identity is now as solid as that for the nominal identity. See Vaissière (2005a). But this body of new information, welcome as it is, does not include anything new from the Chinese side, so to speak, about where the Xiongnu came from or who in fact they were. These questions are as unanswerable today as they were in the mid-twentieth century, claims from other quarters about ostensible Warring States period Xiongnu grave sites having been excavated in Mongolia notwithstanding. Until the origin and early history of the Xiongnu in China, and of their interactions with the various peoples of central Asia known only by name from western sources, is clearer than it now is, any conclusion about the proposed historical identity of the Xiongnu with the Huns must continue to remain tentative. For one article among many representative of the nature of the debate of half a century ago, see Maenchen-Helfen (1955).

That portion of Shiji 123 that refers to An-xi 安息 (*ʔʔan-sək = Arsacids, i.e., the Parthians), includes the one important exception to the early Chinese silence regarding foreign scripts. In this account there is a line that says succinctly “they write in horizontal lines on raw-hide as their way for keeping notes and records” (畫革旁行以為書記).

The term “abugida” refers to a kind of script that uses “a basic form for the specific syllable consonant + a particular vowel (in practice always the unmarked a) and modifies it to denote the syllables with other vowels or with no vowel.” See Daniels (1990, 730).

See Vaissière (2005b, 119–57, et passim).

See Dien (2003). The term sabao 薩保 < MC sat-pawx is the Chinese transcription of Sogdian s’rtp’w (itself from Skt. sārthavāha ‘caravan leader, merchant chief’), and refers to the person who came to serve as the community spokesman (p. 109).

For a complete report on this tomb, including photographs and line drawings, see “Xi’an bei Zhou Liangzhou sabao Shi jun mu fajue jianbao” (Brief Report of the Excavation of the Tomb of Master Shi, the sabao of Liang Prefecture of the Northern Zhou, at Xi’an) prepared by the Archaeological Bureau of Xi’an for the Preservation of Cultural Relics (2005).

In the present state of Tungusic historical linguistics, it is difficult to say with any certainty whether Jurchen is the direct precursor of Manchu, the language of the Qing ruling house and court, or whether Manchu and Jurchen should be viewed on a par as members of a kind of dialect continuum. The late Jerry Norman was inclined toward the latter possibility. See Norman (2014, i).

The Tanguts established an independent state in the far northwest in the late tenth century that lasted until the early thirteenth, when it was conquered by the Mongols and became a part of the Mongol dynasty. See Dunnell (1994). While the Mongol court produced official “dynastic” histories for the Liao and Jin states, and of course for the Song, they did not, for whatever reason, compile any similar history for the Tangut state.

In preparing this translation, I have taken advantage of the careful work of Leon Hurvitz in Poppe and Krueger (1957, 5).

The best recent study of the ‘Phags-pa script is Coblin (2007), from which I have benefitted greatly in preparing the present discussion.

Reprinted in a three volume, western-bound, facsimile edition of the copy held in the Palace Museum in Beijing (Gu gong bo wu yuan 故宮博物院 1957). For an extensive discussion of Manchu-Chinese linguistic, orthographic and lexicographical quiddities, see Mårten Söderblom Saarela (2014). I am grateful to Dr. Saarela (Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin) for corrections and elaborations on a previous draft version of this paragraph.

Item (c) in Figure 15.10 is the pronunciation of the Uighur word in Manchu script; it is orthographically equivalent to the transcription of the written Uighur form. I am grateful to Stephen Wadley (Portland [Oregon] State University) and to my former student Yin Yin Tan for confirming this for me.