Konrad of Megenberg

Undoubtedly, Konrad had to take the standard subjects grammatica, logica, philosophia naturalis, philosophia moralis and mathematica. In this context, he certainly came across Sphera mundi

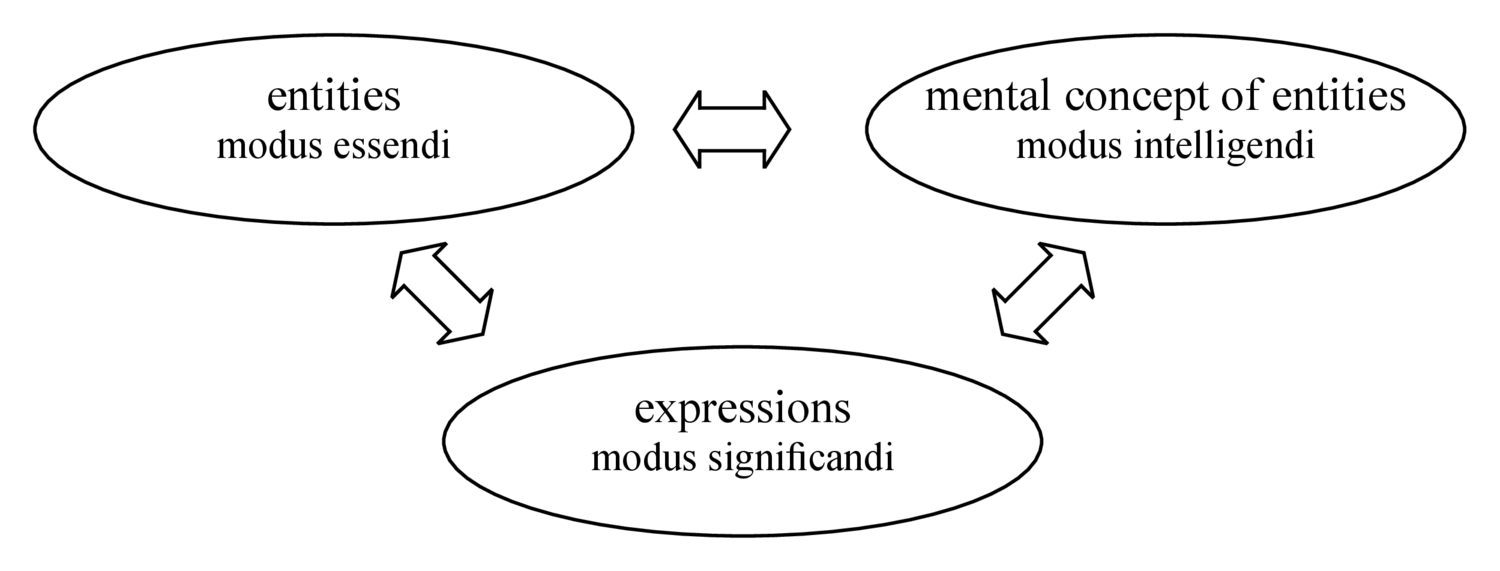

Erfurt was a stronghold of modistic grammar, which is a special kind of realistic language theory

It is not intended here to explain the modistic concept in detail, but we have to consider that Konrad of Megenberg

1330 Konrad relocated to the Sorbonne in Paris where he soon finished his studies in philosophy and obtained the degree of magister actu regens not later than 1343. He was therefore obliged to lecture at the artistic faculty for two years but went on to teach there for eight years and at the same time studied theology.8 In 1343, he became schoolmaster of St. Stefan’s school in Vienna, which is closely involved with the origins of the later prominent university. Five years later, in 1348, he changed to Regensburg and was appointed canon; he also worked as priest at the cathedral of St. Ulrich from 1359 up to 1363. In Regensburg, where he died in 1374, Konrad finished or produced most of his approximately 25 works. The subjects are diverse: theology, canon law, moral philosophy, political science

The first of these is Die deutsche Sphaera

To recapitulate: Konrad had already been working as a tutor or teacher

Concerning language, Konrad had a highly reflected point of view which was ingrained in modistic language theory

Die deutsche Sphaera

While the Latin terminology was already well developed, there was none in German that Konrad could use in his translations. This means that Konrad had to decide how to transfer the Latin, especially the termini technici, into German.

The method verbum e verbo

Fig. 4.2: Comparison between the two translation methods.

Scientific language in medieval translations based on Latin could be described as a “funciolect” of vernacular, which has its own vocabulary

To give some examples: Konrad called the sun’s orbit (ecliptic) scheinprecher, “shine destroyer,” because an eclipse of sun or moon can only happen if the moon crosses this line.13 He named the equator ebennechter, “equinoxer,” because the sun touches this circle twice, when day and night are equally long.14 The horizon he termed as augenender, “eye ender,” because it limits the view.15

Often Konrad offered two or more German terms for one Latin word to clarify an issue, such as halphimel or halpwerld, “half sky” or “half world,” for hemisphere. And the other way around, he used one German word for different Latin

We can assert that Konrad’s terms are really suggestive but his terminology is still quite far from what we expect of scientific terminology from a modern point of view: it is not precisely defined, which would otherwise enable brief and accurate communication. But this is not what Konrad aimed for; he simply wanted to render the text in understandable German.

Let us compare Konrad’s expressions with other cosmological and astrological texts. John of Sacrobosco’s

Even after having compared Konrad’s terminology with those of randomly chosen astronomical codices of the fifteenth century, such as Codex Vindobonensis 3055

Let us now take a closer look at The Book of Nature

Ein wirdig weibes chron,

in welhem claid man die anſicht

so ſint ir tugendleichev werch an chainem end verhandelt.

[...]

Sam tuͤ div edel chunſt:

in welher ſprach man sei durch chift,

doch iſt ſi unverhawen an ir ſelben mit den zungen.

[...]

div red ſchol vnuerſchetet ſein, mit clarheit ſchon vmbſchlungen.

Konrad claimed to be entirely in accordance with the modistic grammar theory

An explanation could be provided by taking a closer look at Konrad’s manner of working, using the example of nomia rerum with which almost every article in The Book of Nature begins. Two cases can be distinguished: the name of an entity either exists in vernacular or it does not.

In the first case, Konrad’s endeavor is to find the correct German equivalent to identify the treated object. To give a basic example: Thaurus haizzt ochſ (Taurus means ochſ, bull).21 Often he used a signal formula like haizzt ze daͤutſch... (that means in German) (III.A.32), which has the function to mark the beginning of a translation of nomina propria

Der ſchaur haizzt in anderr daͤutſch der hagel. (KvM, II.20)

“ſchaur,” the hail, is called “hagel” in a different dialect.

Der chranwitpaum haizt in meinr muͤterleichen dæutſch ein wechalter. (IV.A.20)

“chranwitpaum,” the juniper, is called “wechalter” in my mother tongue.

Ich Megenbergær waͤn, daz deu wurtz, die etzſwa merretich haizt vnd anderſwa chren, radix haizzet ze latein. (V.68)

I, Megenbergær, guess, that the root, which is called somewhere “merretich,” horseradish, and elsewhere “chren,” is named “radix” in Latin.

By giving such alternatives, Konrad enabled his translation to be spread more widely than in just an area where a certain German variety with special nomina propria was used. We can ascertain that manuscripts of The Book of Nature that were written in the eastern upper German area often keep all variants in the text, whereas in those written in other regions frequently only one variant is chosen or even replaced by a name of the own variety.23 This kind of adaption was necessary both to make the text understandable for users and to market it in different areas.

In the second case, there are no existing nomina propria

Nv moͤhſtu ſprechen zuͦ mir: Du nenneſt mir vil tier mit chriechiſchen worten, die ſchoͤlſt du mir zuͦ dauͤtſch nennen oder du bringſt daz lateiniſch puͤch niht reht ze dauͤtſch. Dez antwuͤrt ich dir vnd ſprich, daz div tier vnd andriv dinch, die in dauͤtſchen landen niht ſind, niht dauͤtscher namen habent. Darvmb tuͤſt du mir vnreht. (III.A.19)

Now you will say: You call many animals with Greek or Latinwords; you should use German terms, otherwise your translation from the Latin book is not acceptable. I answer to this, that animals and other things, which do not exist in German countries, have no German names. So you wrong me.

Konrad was determined to bring the Latin

Von dem killen. Kylion oder killon [...] daz mag ein kill haizzen. (III.C.13)

About kill. Kylion or killon, a fabulous marine animal, can be called “kill.”

In the next example, he did the same but added the German name for easier identification:

Tortuca haizt ein tortuk [...] vnd haizzend ez etlich dæutſch læut ein ſchiltchroten. (III.E.33)

Tortuca means “toruk” [...] and many Germans call it “ſchiltchroten,” turtle.

The next example given seems to be of the same type:

Tarans haizt ein tarant. (III.E.34)

Tarans, tarantula, is called “tarant.”

However, tarant was not created by Konrad of Megenberg

Onocratulus mag ze dauͤtſch ein anchraͤtel gehaizzen. (III.B.54)

Onocratulus, the white pelican, can be called “anchraͤtel” in German.

Pellicanus haizt nach der aigenchait der latein grabhauͤtel. (III.B.55)

Pellicanus is called according to his properties in Latin “grabhauͤtel,” grey skinned/skinny.

Implicitly, Konrad dissected the Latin

In other cases, he tried to create new words, which were accurately related to the properties of an entity that was being described:

Concha oder coclea haiſt ein ſnek vnd iſt ze dæutſch als vil gesprochen als ein flæchlink oder ein eytlink, wan ſo der mon ab nimt, ſo werdent ir ſchaln flach hol vnd eytel.

Concha or coclea is called ſnek and it means in German something like “flæchlink,” plainling, or “eytlink,” vainling, because if the moon wanes, its scallops become plain, hollow, and vain.

Another example is the name of the animal denckfuezz (III.C.5) (leftfoot), which has a small right and a big left foot. In these cases, Konrad tried to combine German words in a new way to clarify the foreign name. We call this method loan creation

We see a different but related type, when Konrad used the common German word merjuncfrawe (III.C.18), mermaid, for a marine animal Scilla, because they both have fabulous properties and live in water. The established word has obtained a new meaning; therefore this kind of type is called loan meaning

Konrad’s ambition to create new nomina propria in cases of missing German terms could be explained by the fact that in the Latin

There are many articles in The Book of Nature

Gladiolus haizzet ſlaten chraut vnd haizzt aigenleichen nach der latein swertlinch oder swertchravt darvmb, daz es an ſiner geſtalt iſt ſam ein ſwertes chling. (V.42)

Gladiolus is called “ſlaten chraut” and is actually named according to Latin “swertlinch” or “swertchravt,” “swordling” or “sword herb,” because it is formed like a blade of a sword.

Whereas the astronomical terms

From all this examples, we see that Konrad tried to find adequate German words to denominate and characterize the entities given in The Book of Nature. If no nomina propria existed, he used, as in Die deutsche Sphaera,

References

Bartelink, G. J. M., ed. (1980). Hieronymus—Liber de optimo genere interpretandi (epistula 57): Ein Kommentar. Mnemosyne, bibliotheca classica Batava, Supplementum 61. Leiden: Brill.

Berend, N. (1999). Konrad von Megenbergs “Buch der Natur” (1350): Schriftsprachliche Varianten im Deutsch des 14. Jahrhunderts als Ausdruck für regionales Sprachbewußtsein und dessen Reflexion. In: Das Fr ühneuhochdeutsche als sprachgeschichtliche Epoche: Werner Besch zum 70. Geburtstag. Ed. by W. Hoffmann, J. Macha, K. J. Mattheier, H.-J. Solms, and K. Wegera. Frankfurt a. M.: Lang.

Betz, W. (1944). Die Lehnbildungen und der abendländische Sprachausgleich. Beitr äge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur 67:275–302.

Brendel, B., R. Frisch, S. Moser, and N. R. Wolf, eds. (1997). Wort- und Begriffsbildung in frühneuhochdeutscher Wissensliteratur. Substantivische Affixbildung. Wissensliteratur im Mittelalter 26. Wiesbaden: Reichert.

Deschler, J.-P. (1977). Die astronomische Terminologie Konrads von Megenberg. Ein Beitrag zur mittelalterlichen Fachprosa. Bern; Frankfurt a. M.: Lang.

Gardt, A. (1999). Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaft in Deutschland: Vom Mittelalter bis ins 20. Jahrhundert. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Gottschall, D. (2004). Konrad von Megenbergs Buch von den nat ürlichen Dingen. Ein Dokument deutschsprachiger Albertus-Magnus-Rezeption im 14. Jahrhundert. Studien und Texte zur Geschichte des Mittelalters 83. Boston: Leiden.

Heinfogel, K. (1981). Sphaera materialis. Text und Kommentar. Ed. by F. B. Brévart. Göppinger Arbeiten zur Germanistik 325. Göppingen: Kümmerle.

Köbler, G. (1993). W örterbuch des althochdeutschen Sprachschatzes. Ed. by 4. Paderborn; München: Schöningh.

Konrad von Megenberg (1973–1984). Werke: Ökonomik. Ed. by S. Krüger. Monumenta Germaniae historica 3. Staatsschriften des späteren Mittelalters 5, 1–3. Stuttgart: Anton Hiersemann.

– (2003). Das “Buch der Natur”, II: Kritischer Text nach den Handschriften. Ed. by R. Luff and G. Steer. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Koopmann, C. (2016). Konrad von Megenberg (1309–1374): Weltbild und naturwissenschaftlicher Wortschatz im Buch der Natur. Göppinger Arbeiten zur Germanistik 785. Göppingen: Kümmerle.

Krüger, S. (1971–1973). Krise der Zeit als Ursache der Pest? Der Traktat De mortalitate in Alamannia des Konrad von Megenberg. In: Festschrift f ür Hermann Heimpel zum 70. Geburtstag am 19. September 1971. Ed. by Max-Planck-Institut für Geschichte. 36. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 839–883.

Lorenz, S. (1989). Studium generale Erfordense: zum Erfurter Schulleben im 13. und 14. Jahrhundert. Stuttgart: Hiersemann.

Nischik, T.-M. (1989). ... und haizt ze däutsch ... : Zur Übertragung lateinischer nomina rerum im “Buch der Natur” des Konrad von Megenberg. In: Festschrift f ür Herbert Kolb zu seinem 65. Geburtstag. Ed. by K. Matzel and H.-G. Roloff unter Mitarbeit von B. Haupt und H. Weddige. Bern u.a.: Lang, 494–511.

Scholz, M. G. (1992). Quellenkritik und Sprachkompetenz im “Buch der Natur” des Konrad von Megenberg. In: Festschrift Walter Haug und Burghart Wachinger. Ed. by J. Janota, P. Sappler, and F. Schanze. Tübingen: Niemeyer, 925–941.

Schuler, H. (1982). Lehnpr ägungen in Konrads von Megenberg Traktat “von der sel”: Untersuchunges zum mittelhochdeutschen theologischen und philosophischen Wortschatz. Münchner Germanistische Beiträge 29. München: Wilhelm Fink.

Thomas von Erfurt (1972). Grammatica Speculative. Ed. by G. L. Bursill-Hall. London: Longman.

Wolf, K. (2011). Astronomie für Laien? Neue Überlegungen zu den Primärrezipienten der “Deutschen Sphaera” Konrads von Megenberg. In: Konrad von Megenberg (1309–1374): ein spätmittelalterlicher “Enzyklop ädist” im europ äischen Kontext. Ed. by E. Feistner. Jahrbuch der Oswald von Wolkenstein-Gesellschaft 18 (2010/2011). Wiesbaden: Reichert, 313–325.

Wolf, N. R. (1987). Wortbildungen in wissenschaftlichen Texten. Zeitschrift f ür deutsche Philologie 106:137–149.

Footnotes

See Gottschall (2004, 25–31).

See Lorenz 1989.

See Gardt (1999, 25–38).

See Gottschall (2004, 36–37).

See Gottschall (2004, 75–76).

The third text often ascribed to Konrad is the tractatus Von der sel, written in 1359. It is a translation of chapters 2–7 of Batholomäus Anglicus’ (ca. 1190–ca. 1250) De proprietatibus rerum. The text can only be found in the second version of Buch der Natur. It is arguable whether Konrad was the redactor and even translator of this text, therefore I will not treat Von der sel. Dagmar Gottschall (2004, 21–22) gives convincing arguments concerning the style of translation which cast Konrad’s authorship into doubt. See further Schuler (1982).

See Wolf (2011, 313–318). See further Koopmann (2016, 9–15).

The division of those two methods was already reflected in the ancient world; the Church Father Hieronymus also made this determination in De optimo genere interpretandi, which was written in 415 CE. See Hieronymus (1980).

See Deschler (1977, 305). See also Das Deutsche Wörterbuch von Jacob und Wilhelm Grimm, sub voce “Wiesebaum”: http://woerterbuchnetz.de/DWB/, accessed May 22, 2017.

Konrad von Megenberg (2003, III.A.63), in the follow quoted/cited with roman numbers.

See Berend (1999, 51–53).

An examination of affix-based word formations in The Book of Nature is contained in Brendel et al. (1997).

Referring to Werner Betz’s terminology, this kind of transfer is called “Lehnübersetzung.”

In Betz’s terminology “Lehnschöpfung.”

According to Betz’s terminology it is called “Lehnbedeutung.” For further examples for all those mentioned types, see Scholz (1992, 931).

It seems that Konrad rebuilt the i-umlaut, which changed the long u into the long ü before i, and whose process was already terminated in Old High German times. Besides, he used diphthongization, which changes the long ü to eu in the early New High German period. The ending of the Latin word was left out. This way of adaption is quite remarkable because Konrad used a phonologic pattern with the i-umlaut that was no longer active in his time. See Nischik (1989, 504).