4.1 Elementary actions, instrumental practices, and theoretical knowledge

This chapter is concerned with an analysis of the small body of texts usually referred to as the Mohist Canon

When we call a historical cultural activity ‘science’, we usually justify this by identifying certain features of the activity as in some way ‘scientific’. This practice may relate to such things as the recognition and systematic observation of regularities in the physical world, the explanation of such regularities by causal reasoning

One of the ways to characterize theoretical knowledge is by recognizing that it is not directly related to practical problems. Theoretical knowledge may build upon knowledge from practical experience, but it is not pursued with the direct aim of solving practical problems. Somewhat aphoristically one may say that, while the purpose of practical knowledge is the control of action, the aim of theoretical knowledge is the control of knowledge itself. Theoretical knowledge emerges from the reflection on externally represented knowledge. Spoken language

In addition to theoretical knowledge there are of course other forms of knowledge. We may distinguish elementary and instrumental knowledge, both of which in some sense precede theoretical knowledge. These different forms of knowledge are distinct in their sources, their inner structure, and their modes of transmission. Elementary knowledge is ontogenetically

The relation between space and matter specifically does not first occur in the realm of theoretical reflection but appears as an inherent part of pre-theoretical thinking as a kind of elementary knowledge. In fact, conceptions of space and conceptions of material objects and the relation between the two co-evolve, and in this process space and objects become distinct from each other only gradually. As an illustration of this gradual process of separation consider the experiment in which the Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget

They’re far apart.

But after the investigator has put a cigar box between the two objects, the child says:

It isn’t far, because there’s a wall.

According to this child’s conception, only the ‘empty’

From experiments of this kind, Piaget

Piaget

The structures of elementary and instrumental knowledge do not necessarily find general and consistent expression at the level of linguistic representation. That only comes with theoretical reflection, which entails generality and consistency, giving rise to the appearance and use of abstract terms. Theoretical knowledge may thus be described as emerging from the systematic reflection on external representations of knowledge whereby the knowledge represented may be elementary, instrumental, or itself theoretical. We may distinguish different branches of theoretical knowledge according to form and representational type of the knowledge reflected upon. The systematic reflection on linguistic representations of elementary knowledge, for instance, brings about a branch of theoretical knowledge that may be described as philosophy of space, time, and matter, a prominent example being Aristotle’s Physics

Since external representation of knowledge is a universal

Consider philosophical reflections on spatial concepts, which are the focus of this chapter. As evidenced by the various cultural techniques for spatial orientation and their linguistic representation, including the representation of spatial knowledge in mythologies

Did then theoretical thinking about space emerge only once in history and then survive as a tradition? Or did it come about several times independently and was only accidentally influenced by earlier instances of spatial thinking? More broadly we may ask the following questions of the long-term development of spatial knowledge:

What are the social, material, and intellectual conditions for the emergence of theoretical knowledge on space?

To what extent is later thinking informed by the emergence of a tradition of such theoretical knowledge in antiquity?

To what extent are similar structures in theoretical thinking on space the result of the influence of a single tradition, be it diachronically in a single culture or be it across cultures, and to what extent are such similarities an independent consequence of elementary and instrumental forms of thinking?

What are the social, material, and intellectual conditions for the survival and perpetuation of a tradition of theoretical knowledge?

These are grand questions and addressing them obviously presupposes the comparison of different historical instances on theoretical thinking about space. In particular, historical instances that may be argued to be uninfluenced by the ancient Greek precedent are valuable objects of study in this context. Such instances are very hard to find. Traditions of theoretical reflection of ancient India

4.2 The Mohist Canon

The Mohist Canon is contained in four of the seventy-one chapters that make up the Mohist corpus, known generally simply as the Mozi. The corpus itself is a compilation of texts, perhaps of disparate origins, that dates in its transmitted form to about 300 BCE. Several centuries later it is ascribed by Han period scholars to what they identify as a ‘Mohist school’. The period of the late fifth, fourth and third centuries BCE, known historically as the Warring States Period, is distinguished for the richness of its intellectual ferment and for its growing social and political instability. Numerous texts from this period document the extensive concerns with what we would call social or moral philosophy. To the extent that these texts can be seen as constituting ‘schools’ of thought, they reveal how individual members of the learned classes competed for the attention of rulers across the land and for the consequent status that such attention promised. Argument, disputation and debate, aimed at influencing the ruling elite in matters of both political efficacy and social ethics, was the predominant enterprise of the day. Among these competing factions one group in particular, known traditionally as the Dialecticians (biànzhě 辯者), chose to argue from a perspective of logical

The Mohist Canon deals directly with, among other things, spatial concepts and matters of mechanics

Among sources from ancient China

The first two chapters of the Mohist Canon contain about 180 very short passages, the Canons proper, here designated ‘C’. Two further chapters contain passages that were recognized by Liang Qichao, among others, in the early 1920s to be Explanations, here designated ‘E’, matching the Canons.7 An Explanation is linked to its Canon by means of a head character, i.e., the first character of both canon and explanation is the same. The identity of head character in ‘C’ and ‘E’ turned out to be a crucial clue to the overall structure of the text. A Canon together with its co-ordinated Explanation we call a section. In our numbering of sections we follow Graham.8

4.3 Magnitude, filling out, and interstice

Our analysis starts with section A 55.9

A 55

C: 厚,有所大也。

E: 厚:惟端無所大。

C: hòu ‘having magnitude’ means that there is something in relation to which it (i.e., the thing that has magnitude) is bigger.

E: hòu ‘having magnitude’: Only an end-point has nothing in relation to which it is bigger.

Hòu, which in everyday language means ‘thick’ (in the sense of a material, physical dimension), here implies spatial magnitude and is turned into an abstract term that can be used in other definitions or explanations. Thus, a later section reads:

A 65

C: 盈,莫不有也。

E: 盈:無盈無厚。於尺無所往而不得二。

C: yíng ‘being filled out’ is nowhere not having something.

E: yíng ‘being filled out’: Where there is no filling out there is no magnitude. On the measuring rod

The archaeological evidence for the measuring rod

In this section, the material aspect of the measuring rod

A 66

C: 堅白,不相外也。

E: 堅白:異處不相盈。相非是相外也。

C: jiān bái ‘hard-and-white’ is neither excluding the other.

E: jiān bái ‘hard-and-white’: (Attributes in general) when occurring in different places

The term excluding (wài 外) is to be understood primarily in terms of spatial exclusion but it also implies logical

As A 65 above suggests, the Mohist notion of space entails a dichotomy

A 62

C: 有間,不及中也。

E: 有間:謂夾之者也。

C: yǒu jiān ‘having an interstice’ is (the sides) not joining at the center.

E: yǒu jiān ‘having an interstice’: refers to what flanks it (i.e., what flanks the interstice).

This section refers not simply to an ‘interstice’ (that is what we find in A 63), but to the object(s) in relation to which the interstice occurs. This may seem to be in some respects a subtle distinction, but it appears to be for the Mohist important.

A 63

C: 間,不及旁也。

E: 間:謂所夾者也。尺前於區穴而後於端,不夾於端與區穴。及及非齊之及 也。

C: jiān ‘interstice’ is not reaching to the sides.

E: jiān ‘interstice’: refers to what is flanked. Measurements

To be able to speak of an ‘interstice’ you need two flanking objects that are comparable in their capacity to be identified as boundaries of the interstice. Measuring from an outline with a measuring rod

The two sections A 62 and A 63 are complementary descriptions of the occurrence of an interstice and what defines an interstice. What remains to be described is the substance of an interstice, and for that the Mohists invoke a concrete example:

A 64

C: 櫨,間虛也。

E: 櫨:虛也者兩木之間,謂其無木者也。

C: lú ‘king-post’, the interstices are empty

E: lú ‘king-post’: What is empty

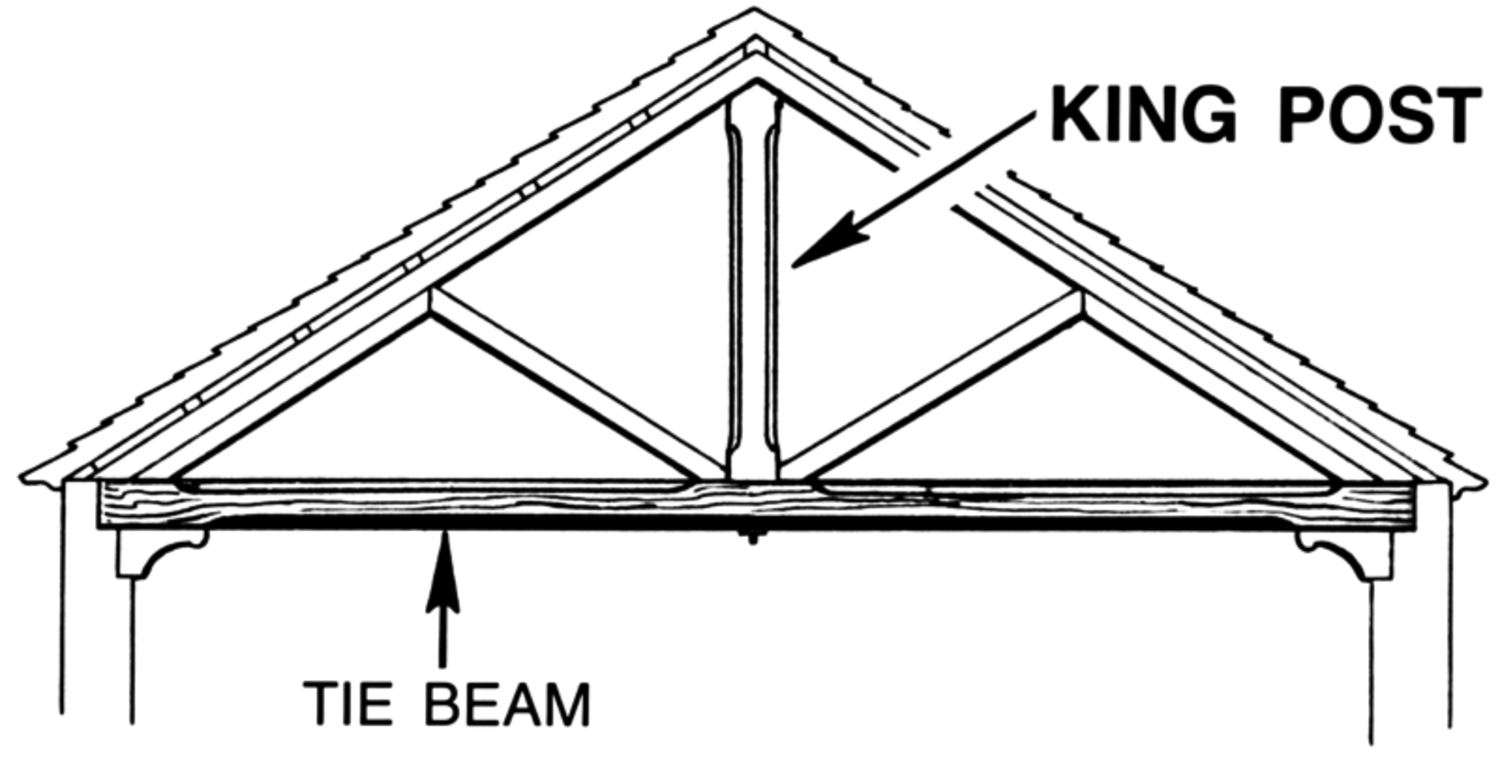

The word lú 櫨 means a kind of ‘rectangular piece of wood mounted on top of a pillar, as used, e.g., in the construction of a roof beam’, what is technically known as a ‘king-post’. It may be defined as “a structural member running vertically between the apex and base of a triangular roof truss” (see figure 4.1).12

The Mohist has recourse to this everyday object to illustrate the relation between an interstice and the material frame that forms it. This takes the understanding of ‘interstice’ one step beyond the descriptions of A 62 and A 63 in that it explicitly recognizes the interstice as ‘empty’

4.4 Spatial extent and duration

We begin with the Mohists’ definition of ‘spatial extent’.

A 41

C: 宇,彌異所也。

E: 宇:東西蒙南北。

C: yǔ ‘spatial extent’ is spanning over different places

E: yǔ ‘spatial extent’: east-and-west entails north-and-south.

What we translate as ‘spatial extent’ is in its more traditional context usually understood as ‘celestial canopy’, a word that generally carries cosmological overtones. Its concrete meaning is ‘eaves’ of a building, or more particularly, the space defined by the eaves. The sense of east-and-west “entailing” north-and-south is that the two directional spans are not separated from each other as independent manifestations of space, but are rather two different aspects or perspectives of a single comprehensive spatial extent.13

The verb mí 彌 here meaning ‘to span, spread (over, out, through)’ with respect to space, is used in a parallel way in the Canon line of section A 40 jiǔ 久 ‘temporal duration’, i.e., ‘temporal extent’, the section that immediately precedes this one in the original Mohist order, given here next.

A 40

C: 久,彌異時也。

E: 久:今古合旦暮。

C: jiǔ ‘enduring’ is spanning different times.

E: jiǔ ‘enduring’: ‘present’ and ‘past’ match ‘dawn’ and ‘dusk’.

Just as yǔ 宇 ‘spatial extent’ is expressed in A 41 as a ‘span’ stretching from one extreme to the other, so this section refers to the extension, or ‘span’, of time of a specific duration, here illustrated by the example of ‘past’ and ‘present’ as an abstract representation of the duration of time correlated with ‘dawn’ and ‘dusk’ as a concrete representation. Sections A 41 and A 40 seen in tandem suggest that the general sense of mí ‘to span, spread (over, out, through)’ is applicable both to space and to time.

The close relation that the Mohist sees between spatial extent and temporal duration also becomes clear in other sections. In particular, space and time are related in discussions of motion and rest.

A 50

C: 止,以久也。

E: 止 : 無久之不止,當牛非馬。若矢過楹。有久之不止,當馬非馬。若人過梁。

C: zhǐ ‘remaining fixed’ means thereby enduring.

E: zhǐ ‘remaining fixed’: The not-remaining-fixed that lacks duration corresponds to ‘ox/non-horse’; like an arrow passing a pillar. The not-remaining fixed that has duration corresponds to ‘horse/non-horse’; like a person passing across a bridge.

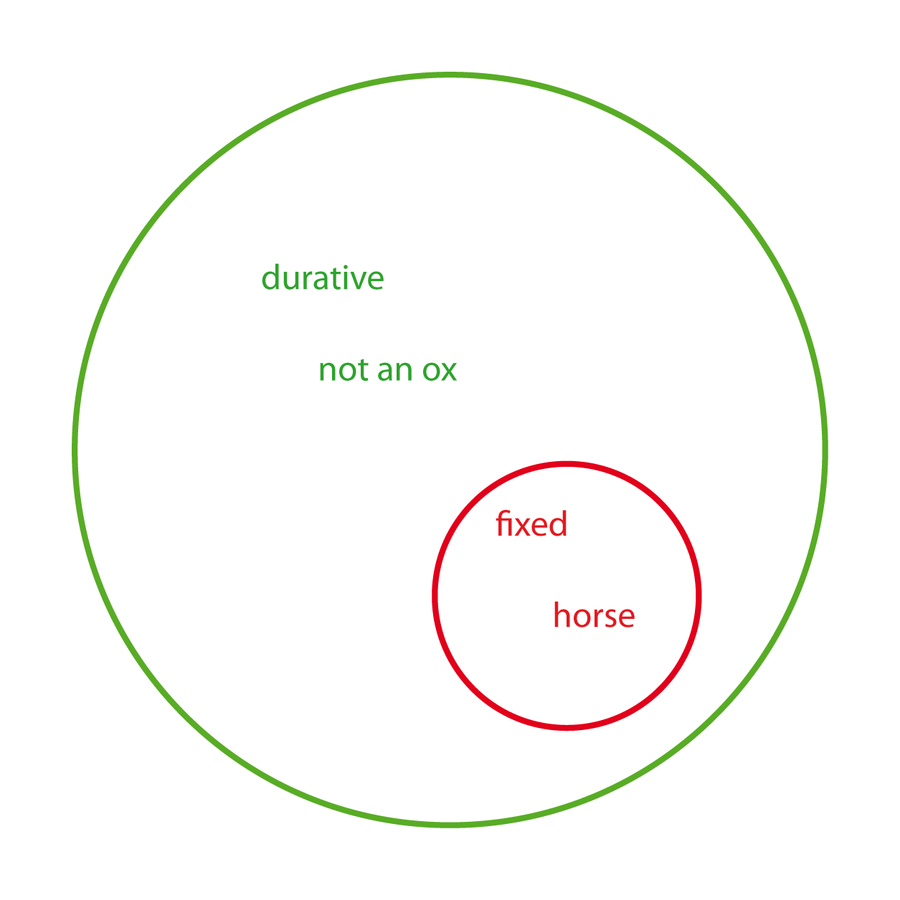

‘Remaining fixed’ means ‘fixed in place

Fig. 4.2: The relation between fixed and durative illustrated in terms of the set relation between ‘horse’ and ‘not an ox’.

The text’s image of “an arrow passing a pillar” is intended to represent the conjunction of ‘not being fixed’ and at the same time ‘not being durative’, since clearly a flying arrow is moving and just as clearly its passing a stationary point, here the ‘pillar’, is perceived as momentary and therefore not durative. Similarly, the image of a person crossing a bridge is just as obviously ‘not fixed’, and also clearly ‘durative’. These two images, together with the original canon statement, represent all logically

The relation between spatial extent and motion is further illustrated in B 13:

B 13

C: 宇或徙,說在長。

E: 宇:長,徙而又處宇。

C: spatial extent, (allows for) a shifting about somewhere. The explanation lies with ‘expanding’.

E: yǔ ‘spatial extent’: as something expands and shifts about it then will occupy further spatial extent.

Space is here associated with a capacity for movement in some direction or another. This shows that spatial extent is not only spanning over different places

B 14

C: 宇久不堅白,說在<?>。

E: 宇:南北在旦,又在暮。宇徙久。

C: (The relation between) spatial extent and temporal duration is not of the hard-and-white type. The explanation lies with <?>.

E: yǔ ‘spatial extent’: South and north exist in relation to the dawn and also exist in relation to dusk. Within spatial extent, shifting about (entails) temporal duration.

The hard-and-white relation type (jiān bái 堅白) is defined as that relation in which one attribute may occur or not independently of the other (see above). But spatial extent exists in connection with the period of the dawn, and again separately in relation to the period of dusk. Furthermore, spatial extent is defined as that which allows for a shifting about (see B 13 above), and because shifting about entails temporal duration, spatial extent therefore has a dependent relation to temporal duration. So ‘spatial extent’ and ‘temporal duration’ are not independent attributes, but are inherently linked. Thus they are not of the hard-and-white type. Yet there is a hard-and-white type relation that holds between temporal and spatial concepts, as the following section shows.

B 15

C: 無久與宇堅白,說在因。

E: 無:堅得白必相盈也。

C: (The relation between) ‘being without duration’ and spatial extent is of the hard-and-white type. The explanation lies with the criterion.

E: wú: When the hard entails the white, each necessarily fills out the other.

The Explanation states that the hard-and-white relation type means that the two attributes are mutually pervasive, each attribute filling out the other, i.e., each is co-incident with (but independent of) the other. The fact of being mutually pervasive is the criterion referred to in the Canon. The relation between the absence of temporal duration, i.e., being temporally punctual, and spatial extent is said to be of this type. Section B 14 has just made clear that the relation between yǔ 宇 ‘spatial extent’ and jiǔ 久 ‘temporal duration’ is not of the hard-and-white type. We now have in a sense the complement to that, the relation between a ‘point in time’ (wú jiǔ 無久 ‘being without duration’) and yǔ 宇 ‘spatial extent’, which is said to be of the hard-and-white type. This implies that a single point in time is conceived of as filling out the whole of space, and in this respect the criterion of being mutually pervasive is met, yet neither of the two is contingent on the other; there is no dependent relation between spatial extent and a moment in time. At each moment in time there is a spatial extent being filled out by it and filling it out, somewhat anachronistically we may term them spaces of simultaneity. Different spaces of simultaneity (for instance the one existing at dawn and the one existing at dusk) are related by the shifting from one to the other, which entails duration, thereby establishing a dependent relation between temporal duration and spatial extent (B 14).

B 16

C: 在諸其所然,未然者。說在於是。

E: 在:堯善治,自今在諸古也。自古在之今,則堯不能治也。

C: Locating something in relation to where (temporally) it is properly so, or where (temporally) it has not yet become so. The explanation lies with being in relation to this (appropriate or inappropriate time).

E: zài ‘locating’: “Yao is good at keeping order.” This is, from a present perspective, locating it in the past. If one were, looking from a past perspective, to locate it in the present, then it would mean that Yao is not able to keep order.

The point seems to be that there is a non-arbitrary relation between events and time. Events are spatial occurrences and by the same token they occur over time. Therefore they are characterized as having both a ‘spatial extent’ (yǔ 宇) and ‘temporal duration’ (jiǔ 久), and this pairing is, according to B 14, not of the hard-and-white type. This means that the two features ‘spatial extent’ and ‘temporal duration’ as they pertain to events (such as Yao keeping order) are dependent in some way each on the other; events are temporally contingent and therefore are not independent of the time in which they occur; thus the example regarding Yao. When located in the proper time he is good at keeping order (an event that is historically recognized, even if legendary from a modern perspective), located in an inappropriate time, he is unable.

4.5 Instruments and arrangements

As the mention of the measuring rod

A 58

C: 圜,一中同長也。

E: 圜:規寫 也。

也。

C: yuán ‘circle’ implies (from) a single center, being of the same length.

E: yuán ‘circle’: When drawing

‘To be of the same length’ and ‘center’ are defined in sections A 53 and A 54, respectively:15

A 53

C: 同長,以正相盡也。

E: 同:楗與框之同長也正。

C: tóng cháng ‘being of the same length’ means that by being laid straight (next to each other) each exhausts the other.

E: tóng ‘the same’: A door barrier-post and a door frame being of the same length is (an example of) being straight.

A 54

C: 中,同長也。

E: 中:自是往,相若也。

C: zhōng ‘center’ implies being of the same length.

E: zhōng ‘center’: extensions starting from this match one another.

The above definition of a circle (A 58) goes hand-in-hand with that of a rectangle in A 59 following.

A 59

C: 方,匡隅四雜也。

E: 方:矩見 也。

也。

C: fāng ‘rectangle’ implies that the frame corners number four and are closed up.

E: fāng ‘rectangle’: When drawing

The Canon would seem to allow for any kind of quadrangle; only the Explanation by virtue of invoking the carpenter’s square excludes all such that do not consist of only right angles. In normal parlance, of course, both the word fāng 方 and the word kuāng 匡 ‘square-frame basket’ would only be used for rectangles.

In several sections on spatial arrangements of objects, the concept of a dimensionless end-point, which is introduced in section A 61, plays a constitutive role.16

A 61

C: 端,體之無厚而最前者也。

E: [null.]

C: duān ‘end-point’ is the element that, having no magnitude, comes foremost.

E: [null.]

Not only do we have the notion of a dimensionless point, but that notion is analytically identified as a part of a network of specialized terminology, as the following passage illustrates.

A 2

C: 體,分於兼也。

E: 體:若二之一,尺之端也。

C: tĭ ‘element’ is a part of a composite whole.

E: tĭ ‘element’: like one of two; an end-point on a measuring rod

A tǐ 體 ‘element’ is not just an accidental or random part of a whole, like a piece of broken chalk, but is a ‘separable component’ of an analyzable whole. The word tǐ is cognate with the word lǐ 豊 ‘ritual vessel’ and by extension with homophonous lǐ 禮 ‘ritual, ceremony’. The semantic implication is that just as a lǐ 豊 ‘ritual vessel’ is a meaningful physical component with a precise, well-defined position and function in a lǐ 禮 ‘ritual or ceremonial performance’ (cf. zhì  ‘the proper order or sequence of ritual vessels in a ceremonial performance’), so a tǐ 體 ‘element’ is a meaningful component in any composite whole, whether concrete or abstract, of a quotidian, non-ceremonial nature.

‘the proper order or sequence of ritual vessels in a ceremonial performance’), so a tǐ 體 ‘element’ is a meaningful component in any composite whole, whether concrete or abstract, of a quotidian, non-ceremonial nature.

The Mohists recognize four different linear relations illustrated by the arrangement of two measuring rods

A 60

C: 倍,為二也。

E: 倍:二,尺與尺俱去一端,是無同也。

C: bèi ‘doubling’ is making two.

E: bèi ‘doubling’: ‘two’ means a measuring rod

The general notion of ‘doubling’ is illustrated very concretely in linear terms by explaining that two identical measuring rods

A 67

C: 攖,相得也。

E: 攖:尺與尺俱不盡,端與端俱盡,尺與端或盡或不盡。堅白之攖相盡,體 攖不相盡。

C: yīng ‘overlapping’ means each entailing the other.

E: yīng ‘overlapping’: is when a measuring rod

This section shows tǐ 體 ‘element’ as part of the Mohist’s specialized terminology used to establish a distinction between two different kinds of ‘overlapping’. The first example of the Explanation depicts ‘overlapping’ in the most straightforward way, one thing partially coinciding with another. The ‘overlapping’ of independent and coinciding attributes, i.e., attributes of a jiān bái type by contrast must by definition be exhaustive because they “fill out” each other, just as the overlapping of two end-points will be exhaustive. Similarly, the two elements (tĭ 體) referred to in the last phrase of the Explanation must be elements of a single object, and their overlapping corresponds to the overlapping of the two measuring rods

A 68

C: 仳,有以相攖,有不相攖也。

E: 仳:兩有端而後可。

C: bǐ ‘side-by-side comparing’ means that there is a part where (two things) overlap one with the other and a part where they do not overlap.

E: bǐ ‘side-by-side comparing’: Only when the two have a (coincident) end-point is this possible.

It is possible, of course, to lay two measuring sticks side by side such that they partially overlap and partially do not, but unless they are positioned such that one end of one of them coincides with an end of the other, there is no meaningful comparison. The explanation of the canon here makes it clear that bǐ ‘side-by-side comparing’ must be of this ‘coincident end-point’ type.

A 69

C: 次,無間而不相攖也。

E: 次:端無厚而後可。

C: cì ‘contiguous’ is having no interstice but not overlapping one with the other.

E: cì ‘contiguous’: Only because the end-point has no magnitude is this possible.

This section shows that the notion of contiguity is possible only because end-points are without magnitude, i.e., dimensionless. Were that not the case, there would have to be either an interstice or an overlapping.

Further sections that may well be related to instrumental knowledge are A 52, A 56, and A 57. Their relation to the use of instruments remains a conjecture because there are no extant Explanations to the Canons.

A 52

C: 平,同高也。

E: [null.]

C: píng ‘being level’ means being of the same height.

E: [null.]

While it remains questionable if this passage is related to the use of leveling instruments, the following two passages are probably related to the use of gnomons

A 56

C: 日中,正南也。

E: [null.]

C: rì zhōng ‘the Sun at the center’ is being due south.

E: [null.]

A 57

C: 直,參也。

E: [null.]

C: zhí ‘to be straight’ is to be in alignment.

E: [null.]

In the case of A 56, the ‘center’ refers to the mid-point on the Sun’s trajectory between rising and setting, which would have been determined with a device such as a gnomon

4.6 The epistemic status of Mohist spatial knowledge

We have claimed that the spatial knowledge documented in the Mohist Canon presented in the foregoing sections results from systematic reflections on the linguistic representation of elementary and instrumental knowledge and therefore constitutes a genuine case of theoretical knowledge. Let us now analyze the reflective character of this knowledge in order to corroborate this claim and to understand better how the different forms of knowledge interact and thereby shape the theoretical knowledge.

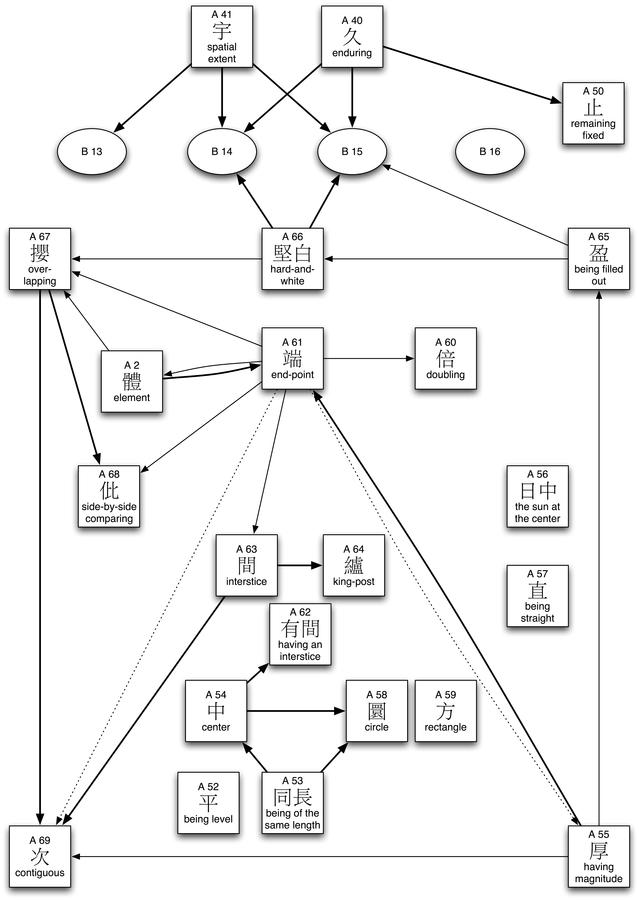

First of all, the representation of knowledge in the Mohist Canon clearly documents second order knowledge, i.e., knowledge resulting from reflections on the representation of knowledge. Thus, the majority of sections we encountered can be identified as definitions, statements that delineate the meaning of specific terms, which are then consistently used. The network of defined terms used in the sections discussed in this chapter is shown in Figure 4.3.

Fig. 4.3: Terminological relations between sections on space, time and matter. Definitions are represented by squares, propositions by ovals. A bold arrow indicates that a defined term is used in the Canon of another section, a thin arrow that it is used in the Explanation. Dotted arrows indicate that the occurrence of the term is only conjectural.

By their participation in a network of definitions, the terms become technical and, to different degrees, abstract. This is an important aspect of the transformation of meaning that takes place when concepts structuring elementary and instrumental knowledge are transferred to the realm of theoretical knowledge. While fundamental aspects of the relevant cognitive structures may be preserved in such transformations, theoretical knowledge inevitably brings about meanings alien to elementary and instrumental knowledge.

Let us, by way of example, look more closely on the relation of space and matter. As explained in the introductory section, within elementary knowledge, space and matter are inherently related ideas. Spatial concepts such as that of distance

How does the relation between space and matter translate into theoretical knowledge? In the case of the Mohist Canon, we have a pair of concepts, hòu 厚 ‘having magnitude’ (being extended) and yíng 盈 ‘filling out’, that consistently differentiate the material and the spatial aspects of bodies. These are the terms defined in sections A 55 and A 65. While we have seen that the distinction between spatial and material aspects of bodies emerges in elementary knowledge, the systematic separation of the two and the reflection on their relation is clearly an aspect of theoretical thinking. Thus, the Explanation provided for the definition of ‘having magnitude’ refers to the duān 端 ‘end-point’, a theoretical entity defined in section A 61. And the Explanation for the definition of ‘being filled out’ (A 65) shows that magnitude is an inherent feature of physical objects and states that spatial magnitude cannot occur without a material filling out.

In a similar manner, sections A 62 and A 63 differentiate yǒu jiān 有間 ‘having an interstice’ and jiān 間 ‘interstice’. The Explanation for the definition of ‘interstice’ clearly demanding that the flanking things that have the interstice are material: the interstice, which may be gauged by means of a measuring rod

The Mohist statement (A 65) that being filled out is a necessary precondition to having magnitude is reminiscent of Western theories of space and matter that claim that extension is a property of bodies alone, not of an alleged space independent of bodies. In a certain way, all theories that hold that space is nothing but an aspect of body maintain this view. Aristotle

But is the Mohist statement actually referring to such a world view, denying extension where there is no bodily filling? The every-day meaning of the term here translated as ‘magnitude’ (hòu 厚) and defined in A 55, ‘to be thick’, suggests that this is really about the magnitude of material objects, not about the question if the abstraction of extension still makes sense when what is abstracted from are bodies in general. In other words, it appears that the Mohist text is actually concerned with the clarification of the use of words, rather than making a claim about the existence or non-existence of space as an entity independent of bodies. If this interpretation is correct, A 65 merely states that the word ‘magnitude’ applies only where there is body (‘filling out’). This interpretation is corroborated by the fact that a term potentially referring to spatial extension without regarding the bodies filling space is given elsewhere in the text: the ‘spatial extent’ (yǔ 宇) of section A 41. After all, this ‘spatial extent’ is defined as spanning over different places

Correspondingly, the canon A 65 on ‘being filled out’ seems not so much to introduce a universal material plenum, but rather to aim at complementing the immediately preceding canon dealing with the empty

It seems that there was no need for the Mohist to position himself in an argument about whether the world was a plenum or whether a perfect void

The discursive context of the Mohist Canon is not so much related to systems of natural philosophy but to rules for consistent reasoning in general. This context is reflected not only in the sections on concepts of knowledge, reasoning, and moral conduct, but also in those on spatial, mechanical, and optical terms.22

In the case of spatial terminology this relation becomes particularly clear from the central role of the term jiān bái 堅白 ‘hard and white’, which is used as a technical term in Warring States disputations. The definition of the term in A 66, in particular, reflects the close entanglement of logical

Besides a concern with the relation between spatial and material concepts, the Mohist text reflects on the relation between the concepts of spatial extent and temporal duration. The Mohist definitions of spatial extent and temporal duration (A 41 and A 40, respectively) are constructed in parallel. The use in both cases of the verb mí 彌 ‘to span, spread (over, out, through)’ clearly indicates that the Mohist conceives of space and time as comparable in that both are extended. The peculiar use of the verb zài 在 ‘to locate’ in a temporal context in B 14 and B 16 underlines this parallelism.

Extension is arguably the most basic structural similarity between space and time.25

More generally, there is strong evidence that a certain parallelism between spatial and temporal concepts is a universal aspect

The Mohist theoretical reflection on the relation between spatial extent and temporal duration again makes use of the concept of ‘hard and white’. Thus, spatial extent and duration are said not to be of the ‘hard and white’ type (B 14). The reason is that they are not independent. Motion is invoked as an argument for this dependence: shifting about implies the occupation of further space (B 13) and takes time (B 14). As a matter of fact, section B 14 seems to suggest the possibility that exemplars of spatial extent can shift through time, viz., the north-south extent from one instant (dawn) in time to another (dusk). Spatial extent and lacking duration, by contrast, are said to be as ‘hard and white’ (B 15), since an instant fills out the spatial extent and vice versa.

While the particular form of the argument is specific to its cultural context, exemplified by the central role of the analytic tool of ‘hard and white’, there are structural commonalities to the spatio-temporal reasoning documented in the Western tradition. The idea that spatial and temporal magnitudes are related by motion, for instance, is also found in ancient Greek philosophy. As an example we may refer to Aristotle’s discussion of the speed of local motion

Despite the parallelism between space and time, there is an asymmetry in their relation as described by the Mohist. It is of spatial extent and lack of duration that the Mohist claims the relation to be of the ‘hard and white’ type, but not of duration and lack of spatial extent. Thus, while one instant in time fills out all spatial extent, the inverse seems not to be the case (a spatial point filling out all of time). Therefore it is instances of spatial extent that shift through time. The asymmetry may be explained by the fact that within spatial extent, motion is conceivable as well as rest. In time, by contrast, there is no rest, spatial extent and all it comprises inevitably move from one instant to the next. This attribute of time, which is not an attribute of space, has been described as transience.30

In his Physics

While the concept of an instant or a ‘now’ has a clear enough sense in elementary thinking, in the realm of theoretical reflection it may become problematic when related to the concepts of motion and rest. In Zeno’s

Just as the the everyday concept of an instant becomes refined in the context of theoretical thinking about motion and rest, the everyday concept of an end-point becomes refined in the context of theoretical thinking about the possible arrangement of measuring rods

In the context of reflections on instrumental knowledge, the Mohist defines further geometrical objects such as the circle or the rectangle. Some of the Mohist geometrical definitions are strikingly reminiscent of parallel definitions in Euclid’s Elements

a plane figure contained by one line such that all the straight lines falling upon it from one point [later called the center] among those lying within the figure are equal to one another[.]

The similarity of this with the Mohist definition of a circle (A 58), definitions that were certainly arrived at independently, may be explained by the similarity of the underlying practical knowledge. In both societies (Warring States China

The near-simultaneous but independent appearance of texts documenting theoretical thinking in Greek and Chinese antiquity raises the question how we might account for this coincidence. Are there identifiable factors that led to this development? This question becomes all the more interesting and all the more consequential when we recognize that the appearance of texts clearly representative of theoretical thinking is a markedly uncommon phenomenon in the ancient world. Whatever form a complete answer to this question might eventually take, here we can observe that both cultures, Greek and Chinese, had thinkers who characteristically constructed paradoxes as inherent parts of their arguments, the Sophists in Greece

Similarities in the independent reflections on spatial concepts in ancient Greece

Another difference we can observe between the Later Mohists’ reflections and their Greek counterparts is that in the Chinese case there seems to be no urge to explain all of nature through certain fundamental principles, mechanisms, or elements, or to formulate encompassing natural philosophies. As concerns possible origins of this disparity between the Aristotelian and the Mohist reflections on spatial terms, the most direct cause appears to be a difference in the timing of the emergence of different types of theoretical debate. In the Greek case, the construction of cosmologies

Finally, a notable difference that renders comparison difficult is the small size of the Chinese text corpus pertinent to theoretical reflections on space. While in Aristotle alone there are whole books devoted to the analysis and discussion of spatial concepts

Bibliography

Aristotle (1983). The Categories. On Interpretation. Prior Analytics. Aristotle in twenty-three volumes. Loeb classical library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

– (1993). The Physics. Aristotle in twenty-three volumes. Loeb classical library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Boltz, William G. (2006). Mechanics in the 'Mohist Canon': Preliminary Textual Questions. In: Studies on Ancient Chinese Scientific and Technical Texts: Proceedings of the 3rd ISACBRST. Ed. by Hans Ulrich Vogel, Christine Moll-Murata, and Gao Xuan. Zhengzhou: Daxiang chubanshe, 32–40.

Boltz, William G. and Matthias Schemmel (2013). The Language of 'Knowledge' and 'Space' in the later Mohist Canon. Preprint 442, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin.

– (forthcoming). Theoretical Knowledge in the Mohist Canon. Berlin: Edition Open Access.

Boroditsky, Lera (2000). Metaphoric structuring: Understanding time through spatial metaphors. Cognition 75(1):1–28.

Casasanto, Daniel and Lera Boroditsky (2008). Time in the mind: Using space to think about time. Cognition 106:579–593.

Descartes, René (1984). Principles of Philosophy. Synthese Historical Library 24. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Euclid (1956). The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements. 2nd edition, revised with additions. Ed. by Heath. New York: Dover.

Evans, Vyvyan (2013). Temporal frames of reference. Cognitive Linguistics 24(3):393–435.

Galton, Antony (2011). Time flies but space does not: Limits to the spatialisation of time. Journal of Pragmatics 43:695–703.

Graham, Angus Charles (1978). Later Mohist Logic, Ethics and Science. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press.

– (1989). Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China. La Salle: Open Court.

Johnston, Ian, ed. (2010). The Mozi: A Complete Translation. New York: Columbia University Press.

Liang Qichao 梁啟超 (1922). Mojing jiaoshi 墨經校釋. Shanghai: Shangwu 商務.

Owen, G. E. L. (1976). Aristotle on time. In: Motion and time, space and matter: interrelations in the history of philosophy and science. Ed. by Peter K. Machamer and Robert G. Turnbull. Columbus: Ohio State Univiversity Press, 3–27.

Piaget, Jean (1946). Le développement de la notion de temps chez l'enfant. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Piaget, Jean, Bärbel Inhelder, and Alina Szeminska (1960). The Child's Conception of Geometry. Digital reprint 2007. Abingdon: Routledge.

Rapp, Christof (2001). Aristoteles zur Einführung. Hamburg: Junius.

Renn, Jürgen and Matthias Schemmel (2006). Mechanics in the Mohist Canon and Its European Counterparts. In: Studies on Ancient Chinese Scientific and Technical Texts: Proceedings of the 3rd ISACBRST. Ed. by Hans Ulrich Vogel, Christine Moll-Murata, and Gao Xuan. Zhengzhou: Daxiang chubanshe, 24–31.

Schiefsky, Mark (2012). The Creation of Second-Order Knowledge in Ancient Greek Science as a Process in the Globalization of Knowledge. In: The Globalization of Knowledge in History. Ed. by Jürgen Renn. Berlin: Edition Open Access, 191–202.

Footnotes

On this issue and the following distinction of forms of knowledge, see the discussion in Chapter 1.

For this third branch, see in particular Chapter 3.

In Han-times (206 BCE – 220 CE) the Dialecticians were retrospectively designated as Nominalists (míngjiā 名家), i.e., as belonging to the ‘School of Names’.

Liang Qichao 梁啟超 1922; Graham 1978, reprint 2003.

Graham 1978. The Chinese text is as established in Boltz and Schemmel forthcoming, and though we are heavily indebted to Graham’s pioneering textual work, our text may sometimes vary from that given in Graham 1978.

The ‘end-point’ (duān 端) occurring in the Explanation line is Graham’s emendation; Graham 1978, 305. Here and in the following, terms that are defined in other sections than the one under consideration are marked in bold face.

See the discussion in Graham 1978, 170–176.

http://dictionary.reference.com accessed 18 October 2013. The image is taken from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:King_post_(PSF).png, last accessed 9 January 2014. We owe the identification of the word lú 櫨 as ‘king post’ to Ian Johnston; Johnston 2010, 428–429.

The question mark (‘<?>’) indicates a defective text.

The term jìn 盡 ‘to be exhaustive’ used in section A 53 is defined in section A 43 (which is not included in this selection) as meaning “that nothing is not so” (莫不然也).

Note that the Chinese term duān 端 is used just as English ‘end-point’, to refer equally to the ‘starting point’ as well as the ‘termination point’ of a line or rod. A rod has two ends, a front end and a back end. Etymologically the word duān in fact suggests a beginning rather than an ending, as is explicitly indicated in this passage.

Section A 2 exemplified a tĭ ‘element’ as an ‘end-point’, yet the overlapping of two end-points cannot be the same thing as the overlapping of two elements, since both elements must belong to a single object, and it is impossible that two end-points of a single object could ever overlap.

Beyond this, cān 參 refers to the three stars of the constellation Orion that in their linear arrangement are identified as Orion’s ‘belt’.

Aristotle Physics IV, 8.

Descartes 1984, 47–48 (Descartes, Principles of Philosophy, Part 2, § 18).

Thus, according to Aristotle’s Categories, for instance, quality and place are two different ways of predicating that which exists; see Rapp 2001, 82.

This becomes clear from Aristotle Physics IV, for instance at 209a, 7–8 (Aristotle 1993, 282).

See, for instance, the recent discussion in Evans 2013. For evidence that the parallelism between space and time is not only a linguistic, but a cognitive, phenomenon, see, for instance, Boroditsky 2000 and Casasanto and Boroditsky 2008.

Aristotle, for instance, describes time and space (place) as quantities related by the fact that they are both continuous, an attribute that presupposes extension; Categories 4b, 24–25 (Aristotle 1983, 36).

Physics 232a, 23 – 232b, 15 (Aristotle 1993, 103–115). See further Physics IV, 11.

Owen 1976, 15; the passage referred to is Physics 219b, 22–33.

Physics 239b, 1–2.

Beyond our concern here with cultures of disputation in China and Greece, such things as political fragmentation and the emergence of city-states, social upheaval and increased social mobility, and the flourishing of arts, crafts, and the technology of warfare all would likely be pertinent to a full account of this development.

On the early Chinese tradition of cosmos-building, see Graham 1989, 315–370.