5.1 Introduction

Our present discussion on cosmological models and epistemologies is a comparison of the different argumentative strategies employed by Aristotle

The epistemological distance between the two main ‘authorities’ of classical cosmology

In spite of this well known criticism of Ptolemy’s ‘abstract mathematics’, it was commonly assumed that his conceptions could be traced back to an essentially Aristotelian cosmology

Before we confront the arguments for geocentricism in Ptolemy and Aristotle, we shall clarify the meaning that we attach to some particularly relevant termini. ‘Cosmology’

Moreover, we shall not assume the term ‘physics’ in the modern sense, but rather in a restricted Aristotelian meaning

5.2 Aristotle

It might be useful to remember that the extant works of the so-called corpus Aristotelicum are generally considered to be the notes of the lectures which the philosopher held at the Lyceum and were later edited by his followers. These writings often resulted from the collection of short treatises, therefore titles are often only labels attached to miscellaneous writings on closely related subjects. This is the case with De caelo ) and II (or

) and II (or

) on the universe as a whole and its parts, book III (or

) on the universe as a whole and its parts, book III (or

) on sublunary elements, and book IV (or

) on sublunary elements, and book IV (or

) on lightness and heaviness. Some scholars pointed out that Chapters 13 and 14 of the second book are apparently a juxtaposition which occurred when De caelo

) on lightness and heaviness. Some scholars pointed out that Chapters 13 and 14 of the second book are apparently a juxtaposition which occurred when De caelo

Aristotle’s confrontation with the cosmologies of his predecessors

In the ‘monograph’ on the Earth, as we might call De caelo

1Pseudo-argument concerning the finiteness of the universe: Aristotle firstly observes that most of those who hold the universe to be finite place the Earth at its center, with the exception of the Pythagoreans

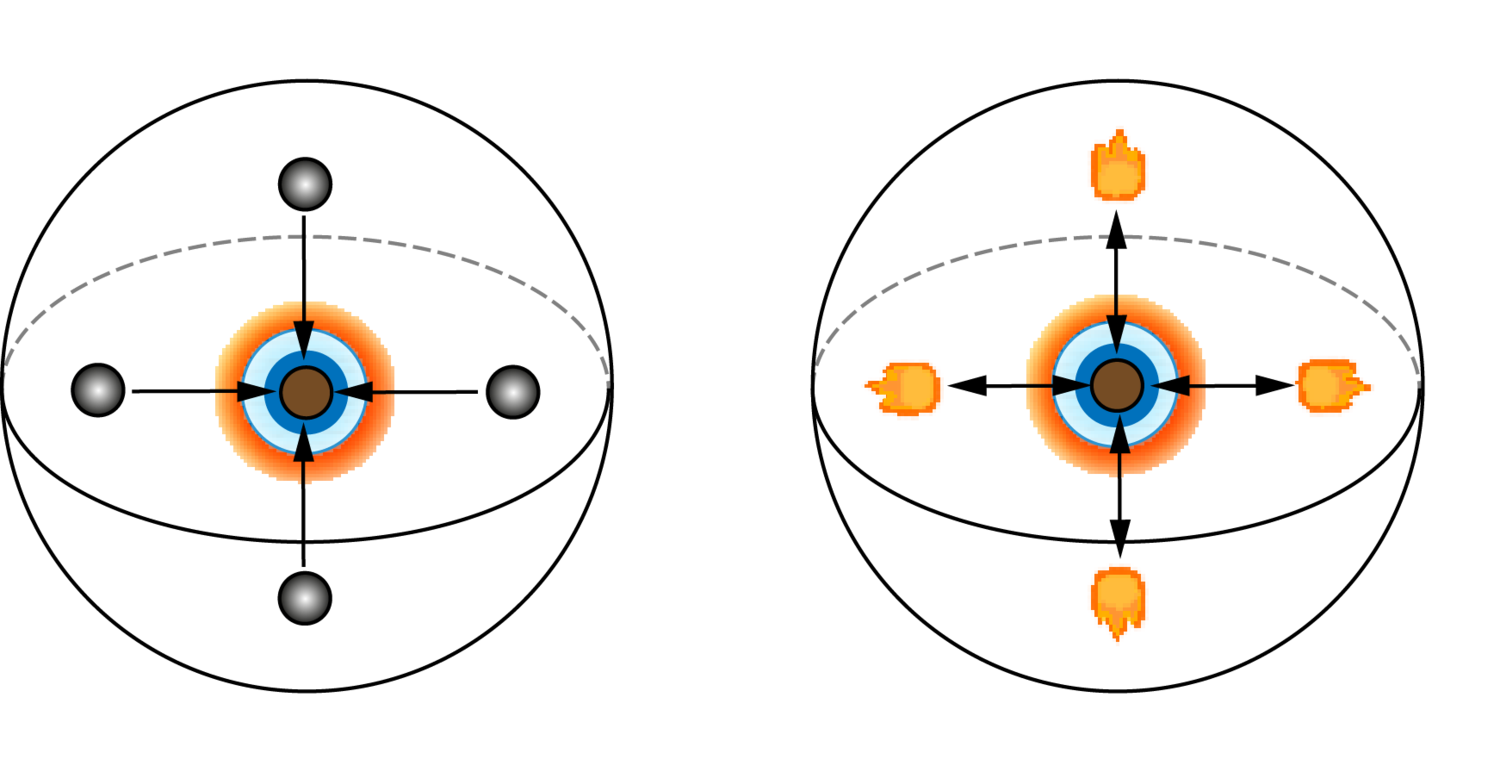

2Argument concerning the fall of bodies:14

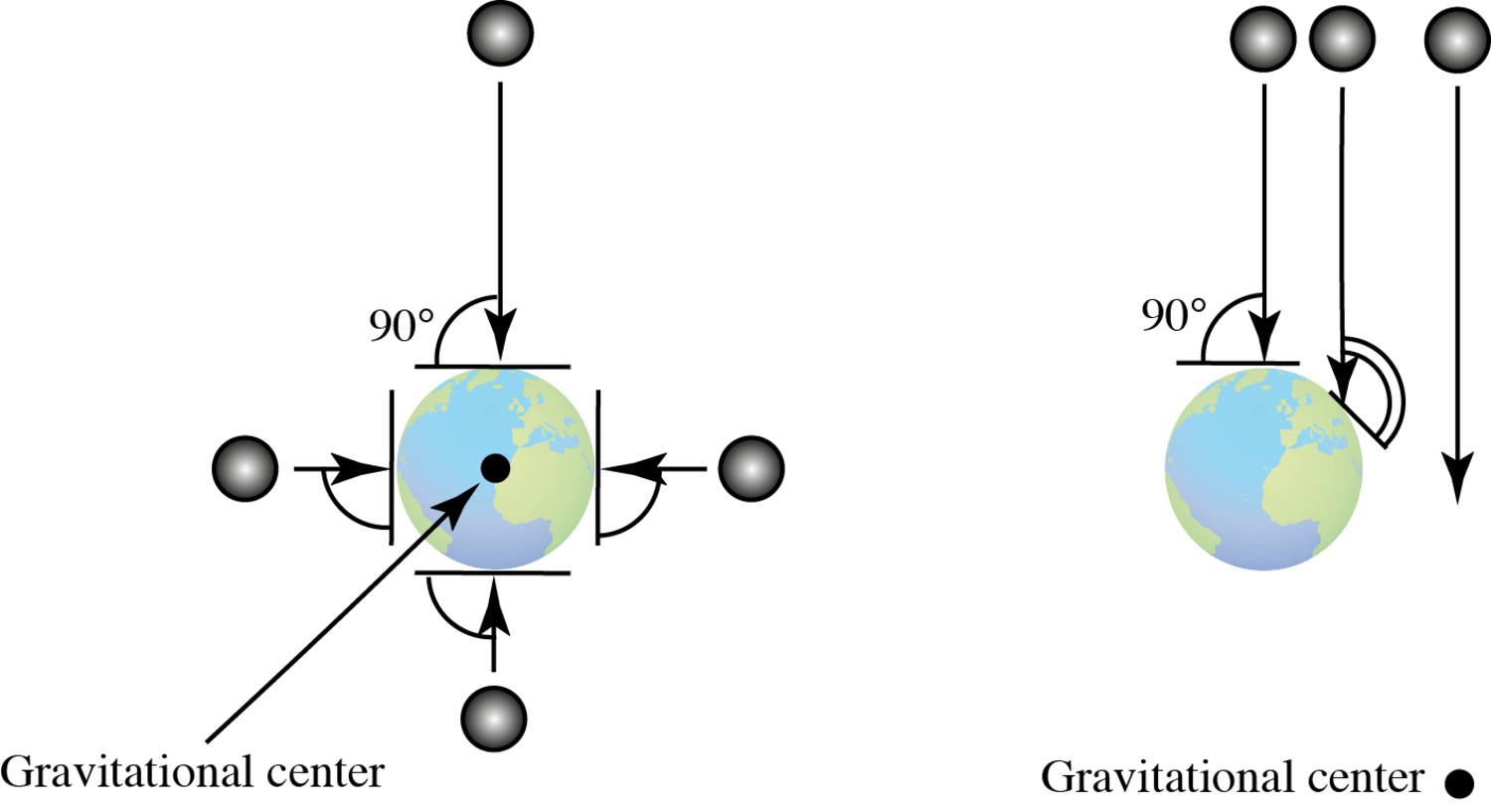

Aristotle argues for the centrality and the position of the Earth based on consideration of the fall of bodies (see Fig. 5.1, left). He assumes that a bigger body falls faster than a smaller one. If the Earth were removed from its central position, he says, it would reach its point of origin very quickly, as a consequence of its huge dimensions. This argument is remarkable for two reasons. First, it seems to be based on a petitio principii. In fact, if the fall of heavy bodies towards the center of the Earth serves as an argument for its cosmological centrality, it is already assumed that the center of gravity and the cosmological center are one and the same. But this coincidence, i.e., the centrality of the Earth (as an element as well as an astronomical body), is precisely what has to be demonstrated. Second, it assumes that the bigger a body is, the faster it travels downwards, an assumption which is supported by empirical evidence only under certain circumstances such as, for instance, when the shape of a falling body and the friction of the medium significantly influence its fall. This argument (which was already questioned in antiquity by atomist

3Pseudo-argument concerning creation:18 Aristotle remarks that those who hold that the cosmos had an origin also believe that the Earth agglomerated at its center. Aristotle not only disagrees on the assumption of a “creation” or “origin” of the world (an issue on which he does not expand here), but also rejects the argument. If one assumed with Empedocles that the various parts of the Earth were brought together by a vortex, one would ignore the fact that up and down have an ontological and epistemological priority over motion. In other words, space determinations should precede spatial displacements:19 “Nor, again, are heavy and light defined by the vortex: rather, heavy and light things existed first, and then the motion caused them to go either to the centre or the surface. Light and heavy, then, were there before the vortex arose […]. In an infinite space

4Argument concerning lightness and heaviness:20 The priority of the theory of natural places

Fig. 5.1: Left: the center of the sublunary world as ‘gravitational’ center

Aristotle’s presentation of his own views

Chapter II,14 deals essentially with Aristotle’s own views. It begins with considerations concerning terrestrial immobility:22 “For ourselves, let us first state whether it [the Earth] is in motion or at rest.” In fact, some thinkers believed that the Earth was a celestial body among others and other philosophers held that it was at the center but rotated about its own axis. As Aristotle already remarked, the former theory belonged to the Pythagoreans

1Argument concerning the categorization of motion:23 Aristotle objects to the geokinetic theories of the Pythagoreans

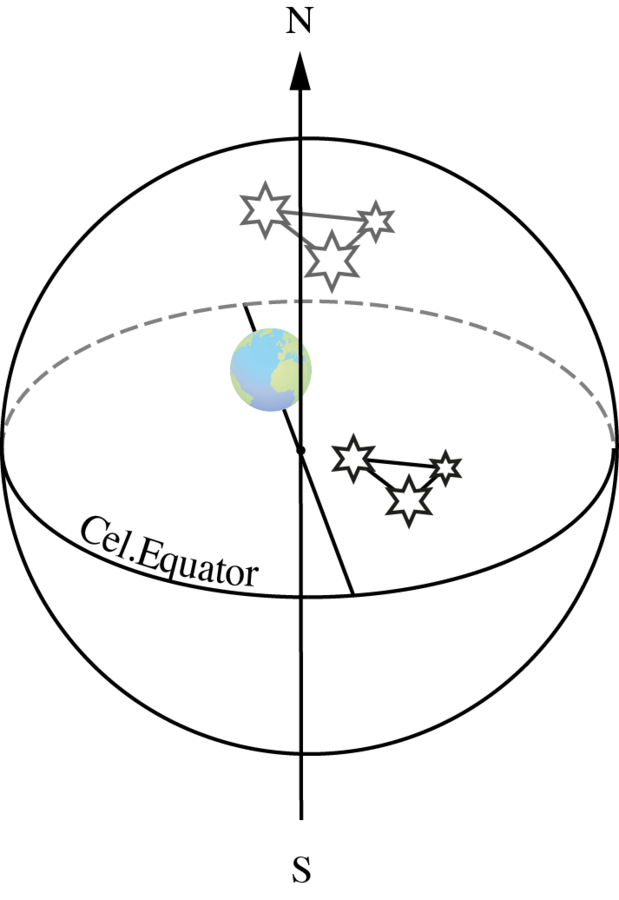

2Argument concerning the rise and setting of stars:24 Aristotle remarks that the terrestrial motion would affect celestial appearances, in particular the fixed stars. This argument is in striking conflict with Aristotle’s previous observation that the Pythagoreans

Following Plato

To sum up, the general meaning of Aristotle’s argument from the rising and setting of the stars is clear, but not its details. It should be additionally noted that this argument is not based on terrestrial physics, as usual, but rather on astronomical considerations.

3Argument from the identity of gravitational and cosmological center

Fig. 5.2: Right: Earth as a gravitational center

4Argument concerning objects thrown upwards: Aristotle adds a remark concerning objects thrown upwards. They will always come back to the ground in a straight line:29 “To our previous reasons we may add that heavy objects, if thrown forcibly upwards in a straight line, come back to their starting-place, even if the force hurls them to an unlimited distance.”

5Argument concerning the simplicity of motion:30 This is a reworking of considerations on natural places

6Confirmation from mathematical astronomy: Mathematical astronomy receives very little acknowledgment from Aristotle. Its role is merely to confirm his views based on mainly physical arguments. As he writes in the conclusion of his defense of the centrality and immobility of the Earth:31 “This belief finds further support in the assertions of mathematicians

about astronomy: that is, the observed phenomena – the shifting of the figure by which the arrangement of the stars is defined – are consistent with the hypothesis that the Earth lies at the centre. This may conclude our account of the situation and the rest or motion of the Earth.”

This argument would later be developed by Ptolemy

Fig. 5.3: Argument concerning mathematical astronomy. The angular distances between the stars

5.3 Ptolemy

[…] the first two divisions of theoretical philosophy should rather be called guesswork than knowledge, theology because of its completely invisible and ungraspable nature, physics because of the unstable and unclear nature of matter; hence there is no hope that philosophers will ever be agreed about them; and that only mathematics can provide sure and unshakeable knowledge to its devotees, provided one approaches it rigorously.

Ptolemy organizes his discussion of mathematical constructs modeling cosmic order along these lines. His basic principles – geocentrism, sphericity of the Earth

Ptolemy’s thorough discussion is organized according to the following scheme (Almagest

1that the heavens move like a sphere;

2that the Earth, taken as a whole, is also sensibly spherical

3that the Earth is in the middle of the heavens;

4that the Earth has the ratio of a point to the heavens;

5that the Earth does not have any motion from place to place;

6that there are two different primary motions in the heavens.

In the following we will discuss the argumentation used by Ptolemy in relation to the first five points.

The last point distinguishes between the daily rotation of the celestial sphere “which carries everything from east to west” (first primary motion) and the motion of Sun, Moon and planets

The heavens move like a sphere

Let us emphasize that the statement that “the heavens move like a sphere” was considered by Ptolemy to be logically equivalent to the statement that “the stars’ trajectories are circular in shape” and vice versa, only because for him the stars were thought to be fixed on the celestial sphere.34

The arguments proposed in the Almagest

They saw that the Sun, Moon and other stars were carried from east to west along circles which were always parallel to each other, that they began to rise up from below the Earth itself, as it were, gradually got up high, then kept on going round in similar fashion and getting lower, until, falling to Earth, so to speak, they vanished completely, then after remaining invisible for some time, again rose afresh and set; and [they saw] that the periods of these [motions], and also the places of rising and settings, were, on the whole, fixed and the same.

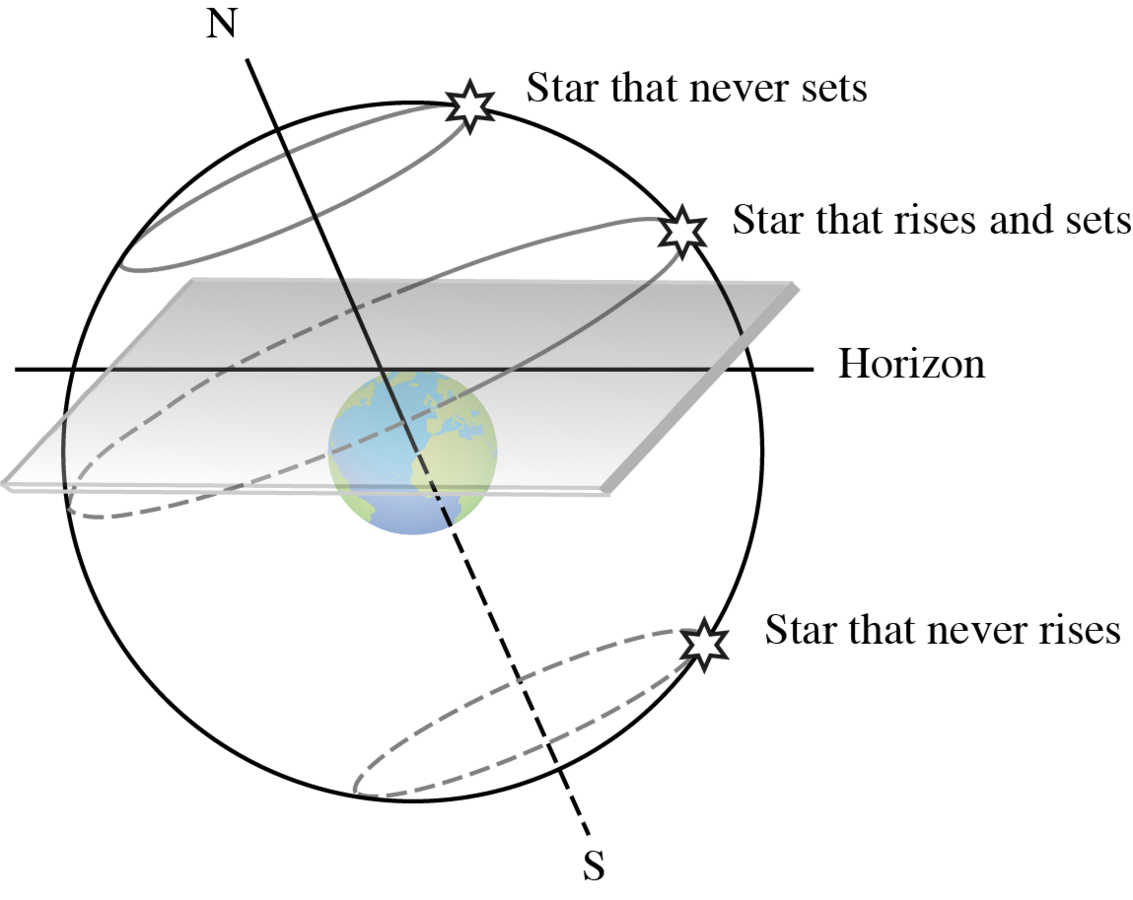

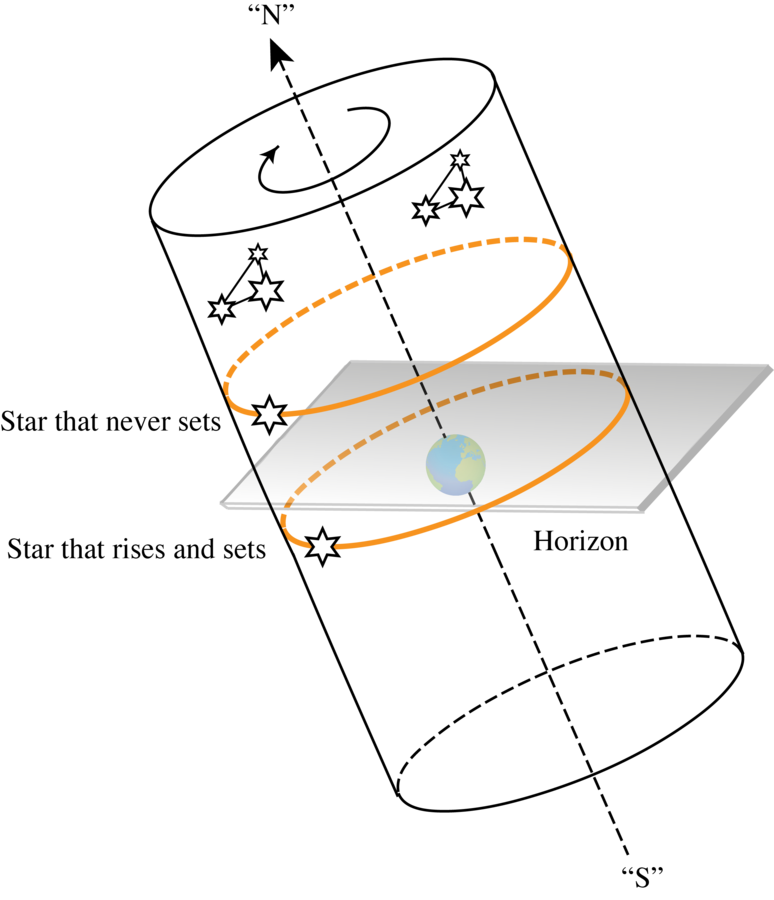

Ptolemy further qualifies the observational evidence for the revolution of always-visible stars and the motion of partly invisible stars. The observational arguments concerning the former, that

their motion is circular and always takes place about one and the same center;

that point becomes the pole of the heavenly sphere for observers;

and those stars which are closer to the pole revolve on smaller circles;

and concerning the latter, that:

those stars that are near the always-visible stars remain invisible for a short time;

and those further away remain invisible for a long time in proportion to their distance

are visualized in Fig. 5.4.

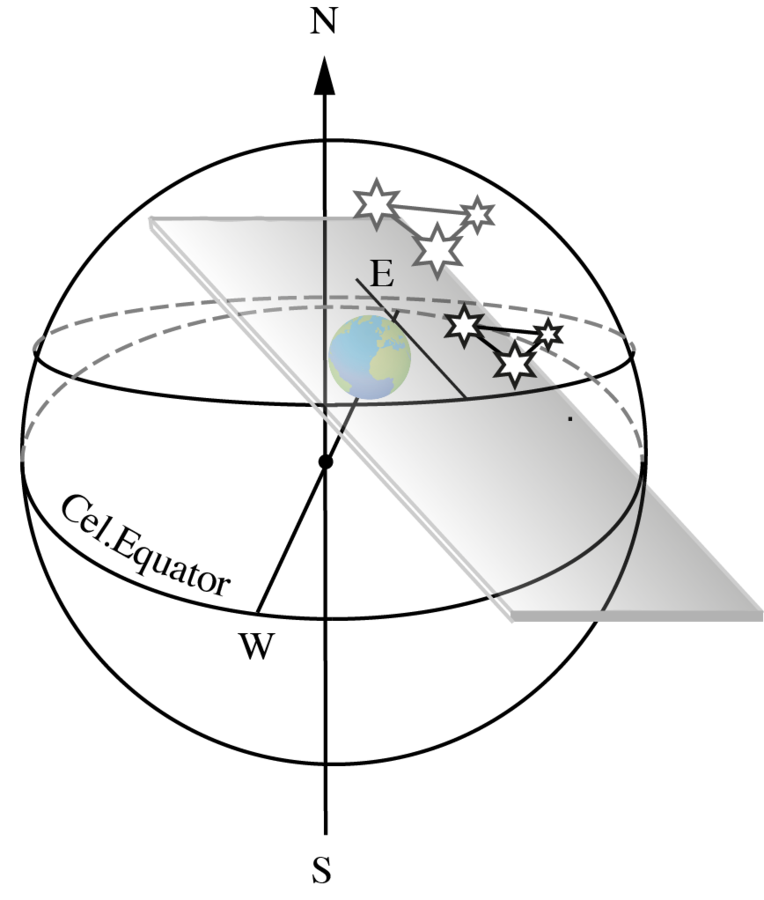

Fig. 5.4: Always-visible stars and stars that rise and set at a given geographical position. Here and in the following we will depict the horizon plane drawn at an observer’s position by a grey shadowed surface.

Obviously, these arguments are of ‘local’ geographical character: they can be put forward after just two nights of observations, without comparison to observational data from different places

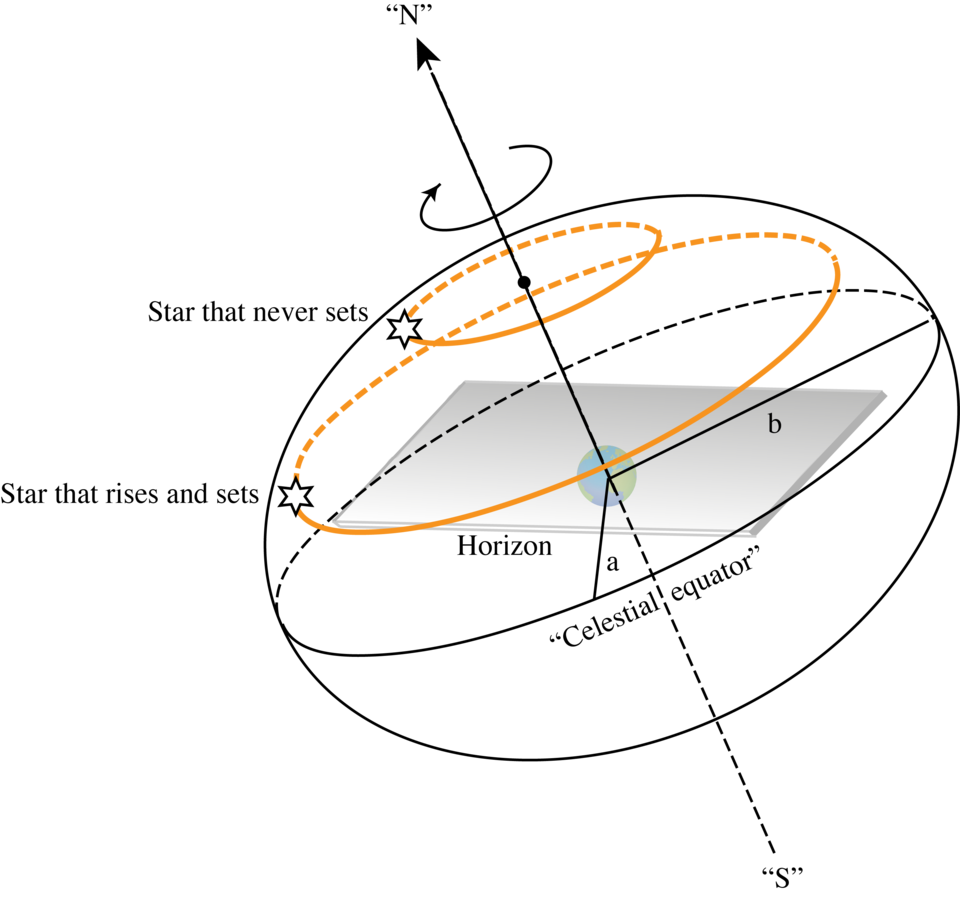

Discussing the consequences of these observational facts on astronomical knowledge, Ptolemy stresses that “absolutely all phenomena are in contradiction to the alternative notions which have been propounded.”38 It is interesting to note how deeply the paradigm of the sphericity of the cosmos

Fig. 5.5: Observational effects in the ‘cylindrical universe’. The stars’ visible trajectories are concentric circles; the local horizon defines the different sets of always-visible stars and stars that rise and set. The mutual distances between stars

The other possible mathematical solution overlooked by Ptolemy is a rotational three-axis ellipsoid. For the special sort of ellipsoid with two equal axes rotating about the remaining axis, the observational effects will be the same as in the spherical universe

Fig. 5.6: Observational effects in the ‘ellipsoidal universe’. Fixed stars lie on the surface of an ellipsoid with two equal axes (

As alternative hypotheses accounting for the visible paths of the stars, Ptolemy mentions only the untenable opinion (perhaps held by Xenophanes)40 that stellar motions might occur in a straight line towards infinity

“[…] What device could one conceive which would cause each of them [stars] to appear to begin their motion from the same starting-point every day?”

“How could the stars turn back if their motion is towards infinity

“[…] If they did turn back, how could this not be obvious?”

In this case “[…] they must gradually diminish in size until they disappear, whereas, on the contrary, they are seen to be greater at the very moment of their disappearance […]”

The first three counter-arguments have a touch of ‘commonsense’ reasoning or a purely rhetorical character. The last argument is totally fabricated: Ptolemy himself refers to this phenomenon a couple of lines later as being caused “by the exhalations of moisture surrounding the Earth being interposed between the place from which we observe and the heavenly bodies.”42

Additionally, Ptolemy refers to another hypothesis which he regards as “completely absurd,” namely, that “the stars are kindled as they rise out of the Earth and are extinguished again as they fall to Earth.”43 Nevertheless, he discusses this issue thoroughly.44 Not only the necessity of cosmic order should rule this hypothesis out – because otherwise “the strict order in their size and number, their intervals, positions and periods could be restored by such a random and chance process” (in fact, the process need not necessarily be “random”) – but also some other objections of special interest are proposed. Ptolemy mentions that, if this were the case, then

“[…] One whole area of the Earth has a kindling nature, and another an extinguishing one, or rather that the same part [of the Earth] kindles for one set of observers and extinguishes for another set; and that the same stars are already kindled or extinguished for some observers, while they are not yet for others […]”

For the stars which are ever-visible in certain regions and are partly-visible at others, one should admit “that stars which are kindled and extinguished for some observers never undergo this process for other observers.”

These counter-arguments are really of ‘global’ geographical character: they can be put forward only through comparison of observational information gained at different geographical localities.

Ptolemy also presents some arguments from mathematical astronomy for the sphericity of the cosmos

“[…] If one assumes any motion whatever, except spherical, for the heavenly bodies, it necessarily follows that their distances

“[…] Since of different shapes having an equal boundary those with more angles are greater [in area or volume], the circle is greater than [all other] surfaces, and the sphere greater than [all other] solids,46 [likewise] the heavens are greater than all other bodies.”

“No other hypothesis can explain how sundial constructions produce correct results […]”

In fact, the first argument refers to the constancy of the stars’ mutual distances

The second counter-argument is of a curiously mixed nature: a correct mathematical result intermingled with a still-naive interpretation of an extremal principle – a future tradition which survived until Leibniz

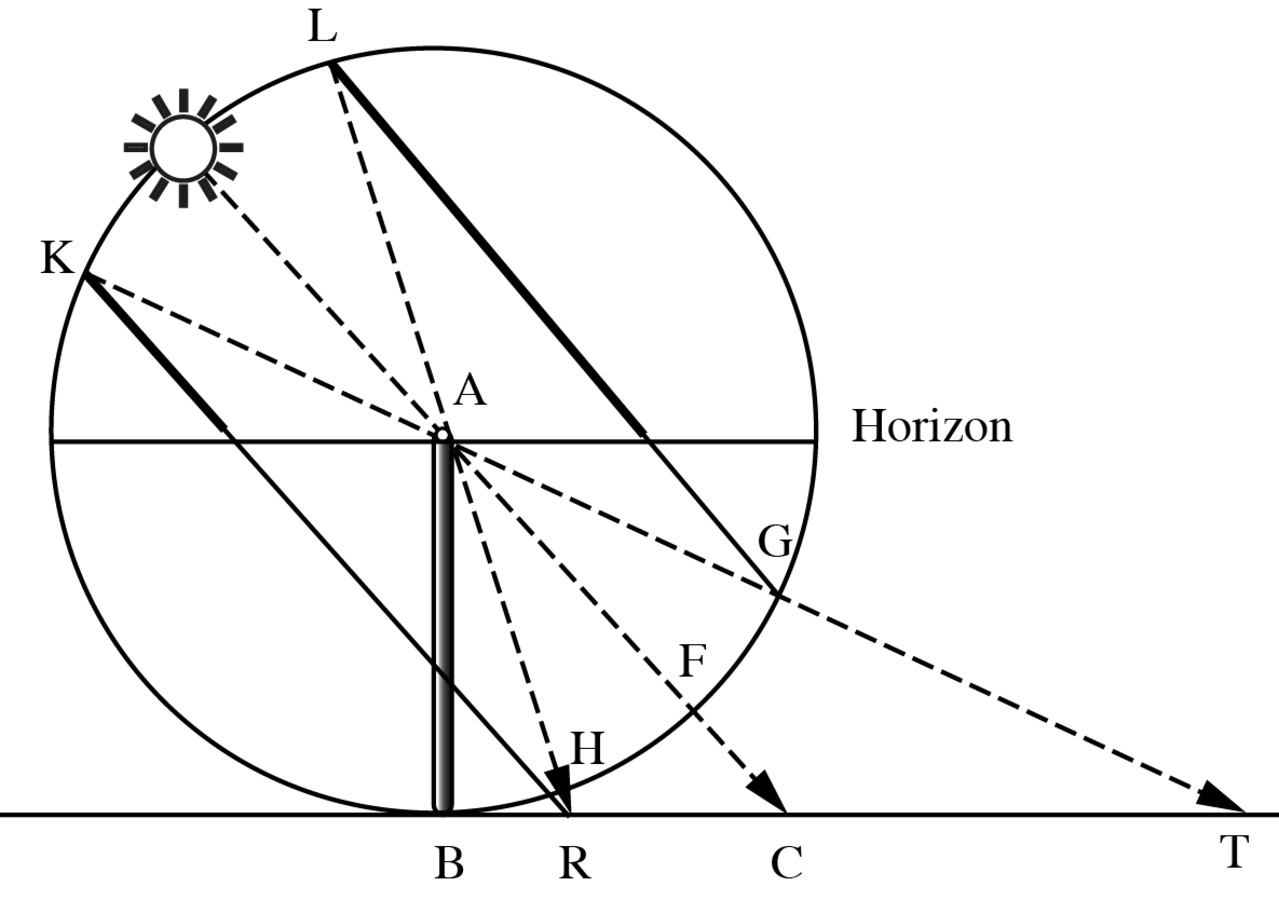

How basic the concept of celestial sphere was for sundial constructions is widely discussed in the literature:47 astronomical calculations with gnomons

marks the end of the shadow at summer solstice; point

marks the end of the shadow at summer solstice; point

marks the winter solstice. Bisecting the arc

marks the winter solstice. Bisecting the arc

and marking this point with

and marking this point with

one gets the point of equinox

one gets the point of equinox

at the prolongation of the line

at the prolongation of the line

. Obliquity of the ecliptic is depicted by the angle

. Obliquity of the ecliptic is depicted by the angle

.

.Fig. 5.7: The gnomon marks the end of the shadow at summer solstice; point

marks the end of the shadow at summer solstice; point

marks the winter solstice. Bisecting the arc

marks the winter solstice. Bisecting the arc

and marking this point with

and marking this point with

one gets the point of equinox

one gets the point of equinox

at the prolongation of the line

at the prolongation of the line

. Obliquity of the ecliptic is depicted by the angle

. Obliquity of the ecliptic is depicted by the angle

.

.

For completeness and to show the actual path of Ptolemy’s argumentation, we will list the arguments which he himself classifies as ‘physical’:

“[…] The motion of the heavenly bodies is the most unhampered and free of all motions; and freest motion belongs among plane figures to the circle and among solid shapes to the sphere […]”

“[…] The aether

“[…] Nature formed all earthly and corruptible bodies out of shapes which are round but of unlike parts, but all aetherical

The Earth, taken as a whole, is sensibly spherical

The arguments aimed at demonstrating the sphericity of the Earth were widely known in Antiquity and are repeated by Ptolemy; the specification “taken as a whole” should indicate that one ignores the local irregularities of the Earth’s surface. For the sake of completeness, Ptolemy also considers some other possible forms for the Earth (concave, plane, of polygonal shape, cylindrical) and shows which astronomical evidence would rule out these cases.

5.3.1 The Earth is in the middle of the heavens

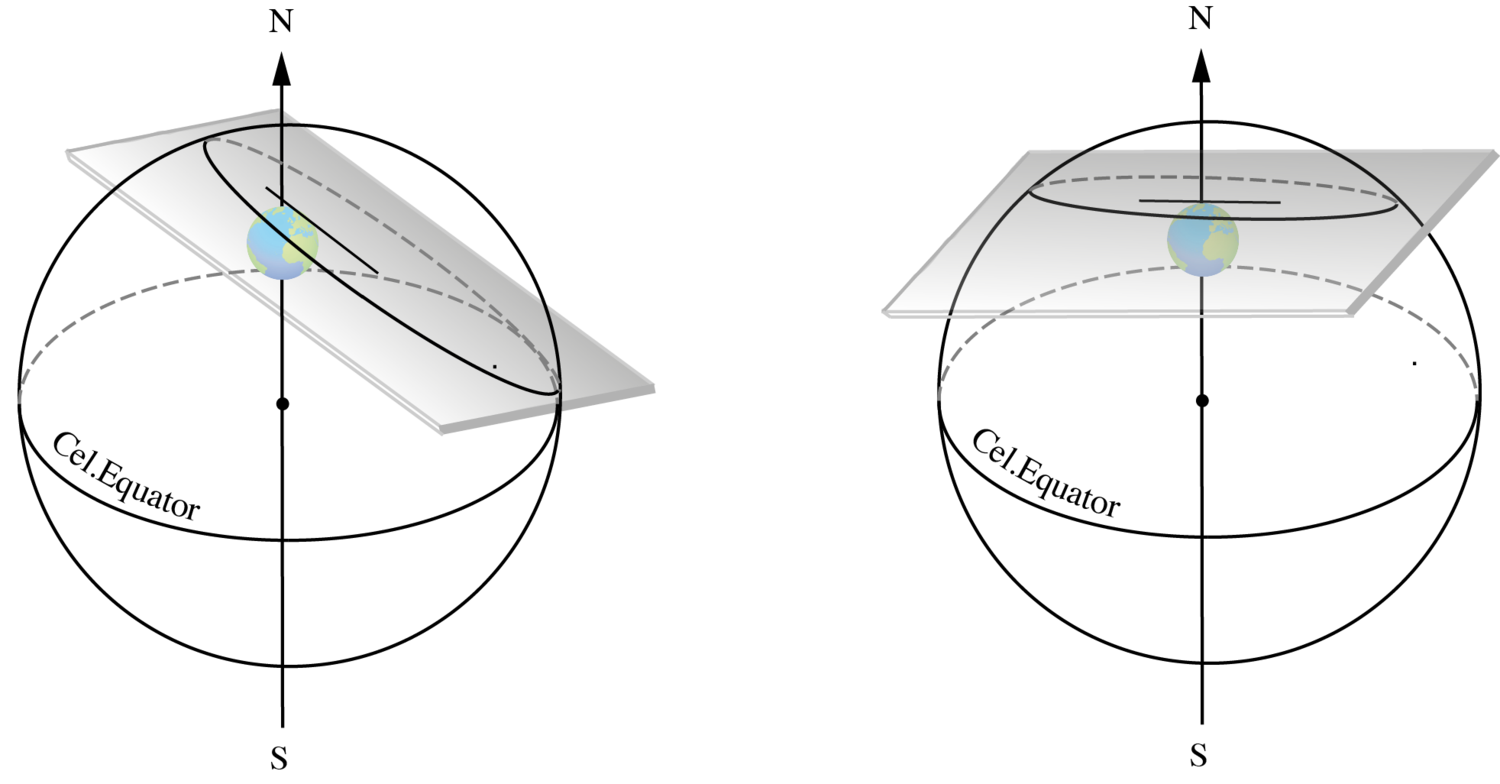

Ptolemy treats geocentrism and enlists a series of astronomical arguments in favor of this thesis in Alamagest I,5. Ptolemy tries to consider all other possible cosmological arrangements with an eccentric Earth and rules them out on the basis of pure observations. The alternatives are the following:

1that the Earth is not on the axis [of the universe] but equidistant from both poles,

2it is on the axis but removed towards one of the poles,

3it is neither on the axis nor equidistant from both poles.

Let us consider the first case. Two possible positions for the Earth are given in Fig. 5.8.

Fig. 5.8: First case: the Earth is equidistant from both poles – two possible locations.

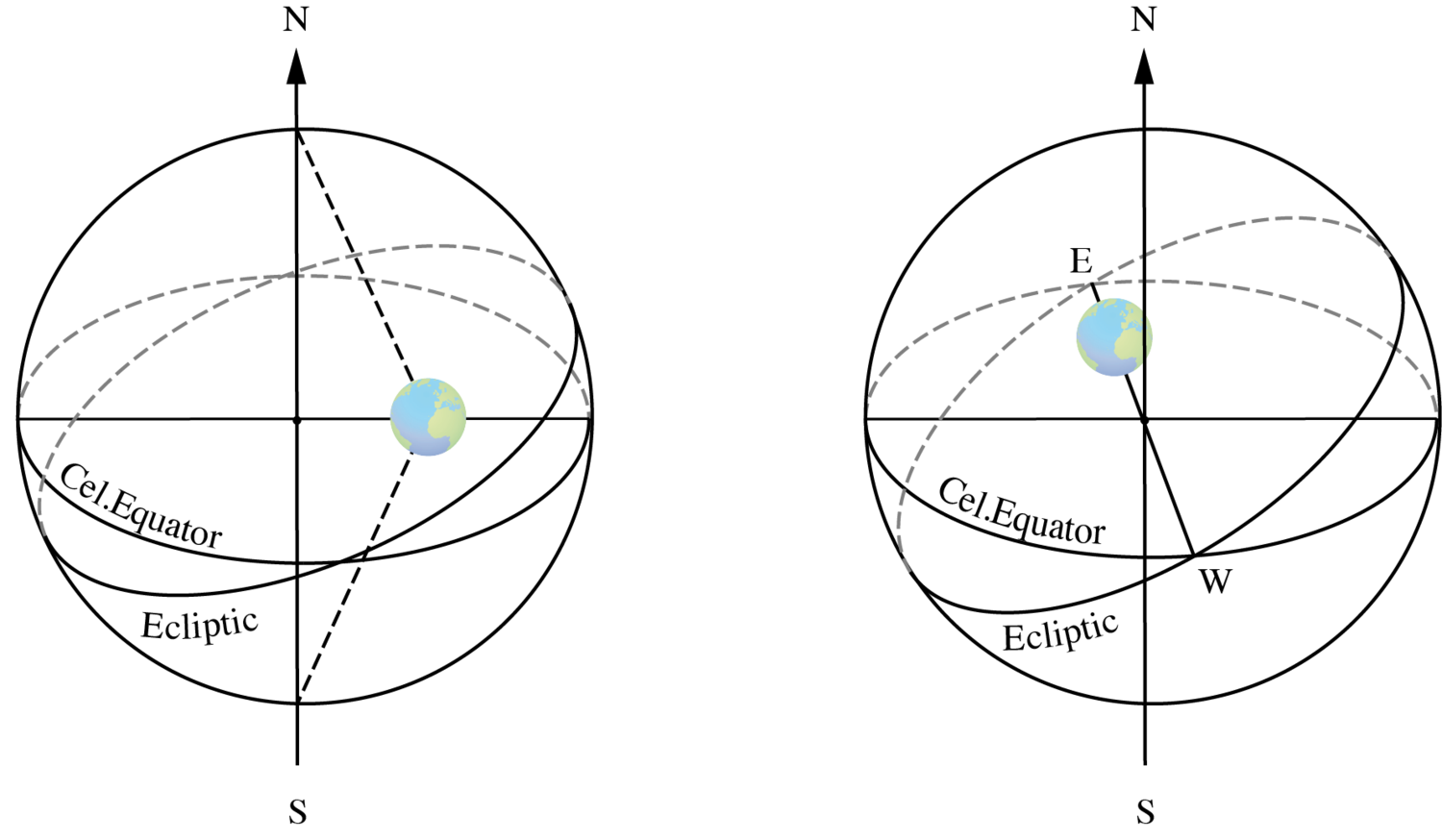

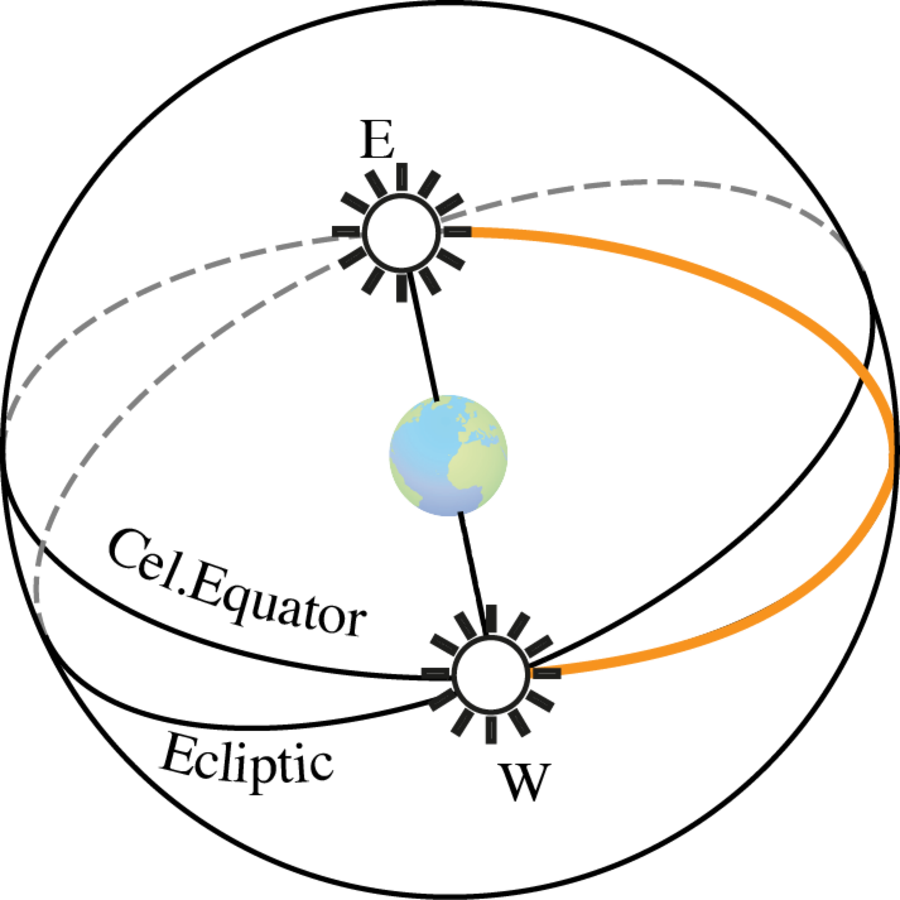

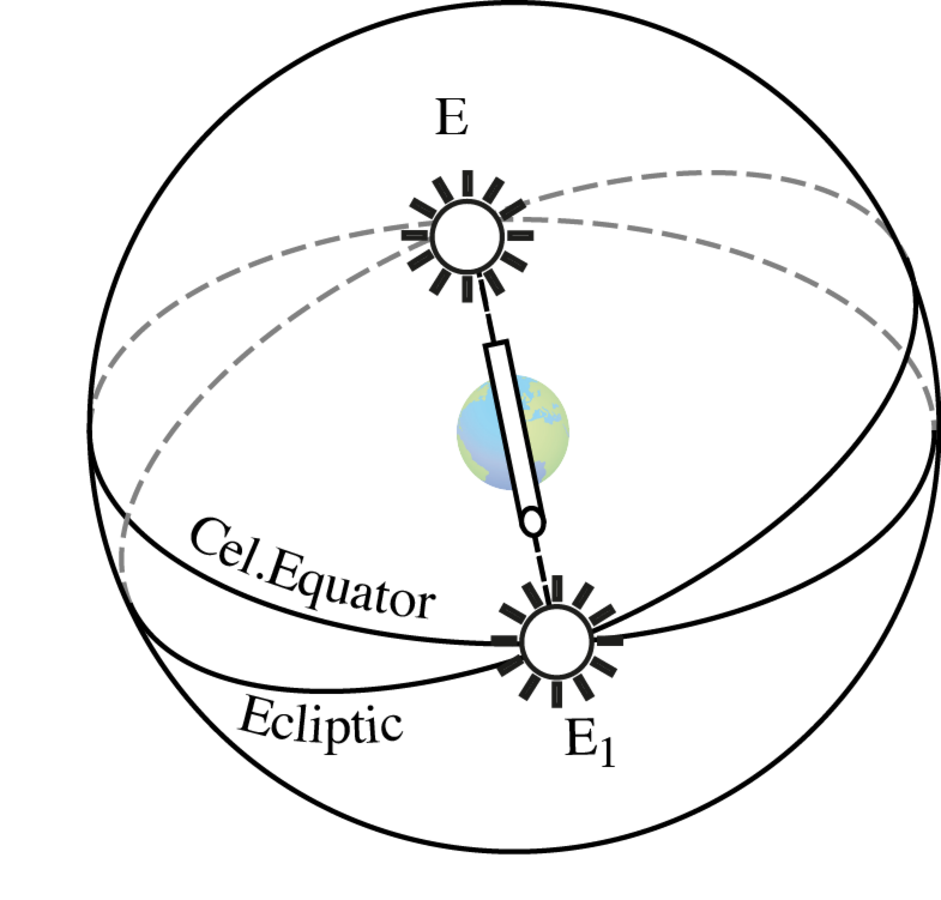

In order to understand Ptolemy’s arguments, it is useful to recall that only if the Earth is in the center of the celestial sphere will the Sun rise for any observer exactly at the east point and set at the west point only twice a year, namely at equinoctials.48 The equinox is defined as a day when the Sun’s declination

, that is, the Sun’s trajectory lies on the celestial equator, and the length of the day is equal to the length of the night (see Fig. 5.9).

, that is, the Sun’s trajectory lies on the celestial equator, and the length of the day is equal to the length of the night (see Fig. 5.9).

and the visible path of the Sun coincides with the celestial equator.

The Sun rises directly in the east and sets directly in the westerly direction for every observer on the Earth’s surface. Here and in the following, we will depict the visible path of the Sun above the horizon plane with a thick line.

and the visible path of the Sun coincides with the celestial equator.

The Sun rises directly in the east and sets directly in the westerly direction for every observer on the Earth’s surface. Here and in the following, we will depict the visible path of the Sun above the horizon plane with a thick line.Fig. 5.9: Equinox: the Sun’s declination

and the visible path of the Sun coincides with the celestial equator.

The Sun rises directly in the east and sets directly in the westerly direction for every observer on the Earth’s surface. Here and in the following, we will depict the visible path of the Sun above the horizon plane with a thick line.

and the visible path of the Sun coincides with the celestial equator.

The Sun rises directly in the east and sets directly in the westerly direction for every observer on the Earth’s surface. Here and in the following, we will depict the visible path of the Sun above the horizon plane with a thick line.

Ptolemy argues:49

If the image [the Earth] removed towards the zenith or the nadir of some observer,50 then, if he were at sphaera recta, he would never experience equinox, since the horizon would always divide the heavens into two unequal parts, one above and one below the Earth; if he were at sphaera obliqua, either, again, equinox would never occur at all, or [if it did occur], it would not be at a position halfway between summer and winter solstices, since these intervals would necessarily be unequal, because the equator, which is the greatest of all parallel circles drawn about the poles of the [daily] motion, would no longer be bisected by the horizon; instead [the horizon would bisect] one of the circles parallel to the equator, either to the north or to the south of it. Yet absolutely everyone agrees that these intervals are equal everywhere on Earth, since [everywhere] the increment of the longest day over the equinoctial day at the summer solstice is equal to the decrement of the shortest day from the equinoctial day at the winter solstice.

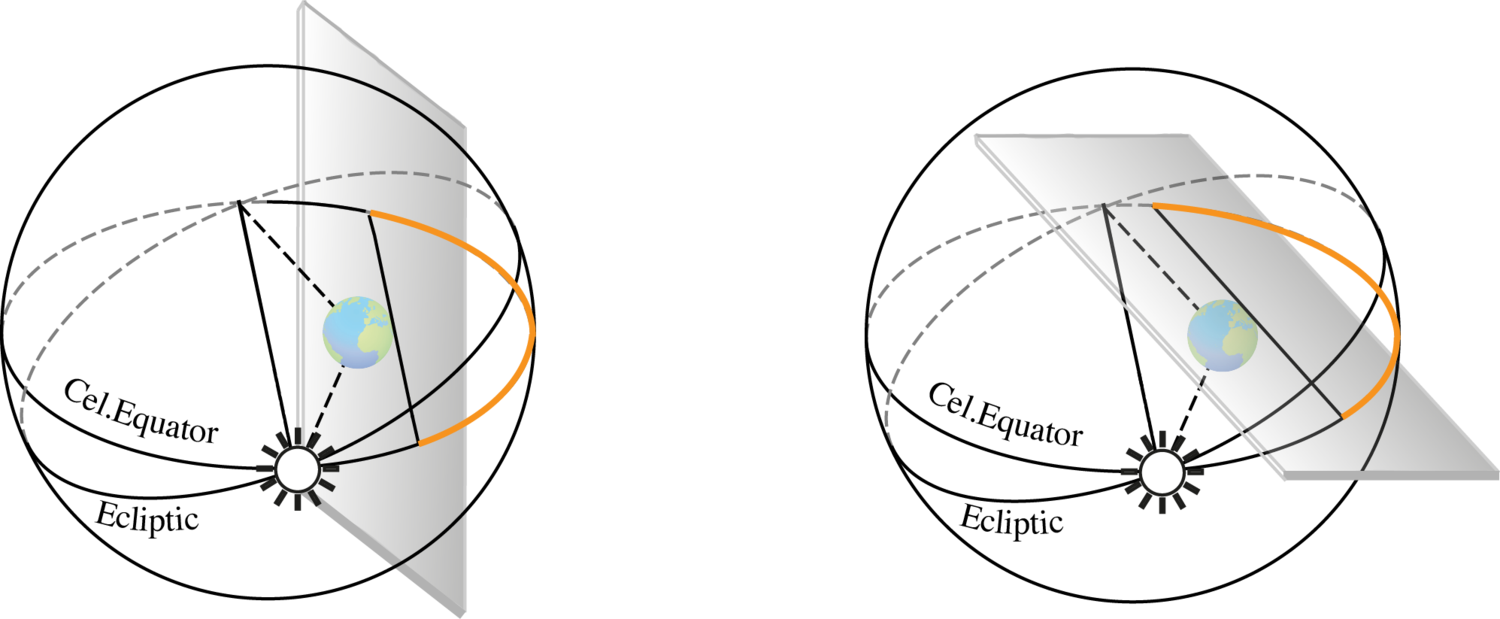

Ptolemy considers separately two possible positions of observation, one at the equator (sphaera recta) and another at an arbitrary latitude (sphaera obliqua). He concludes, in fact, that in both cases one would never experience an equinox, since the horizon would always divide the heavens into two unequal parts. The argumentation is visualized in Fig. 5.10.

. Observational situation at sphaera recta (left) and at sphaera obliqua (right).

. Observational situation at sphaera recta (left) and at sphaera obliqua (right).Fig. 5.10: The Sun’s declination

. Observational situation at sphaera recta (left) and at sphaera obliqua (right).

. Observational situation at sphaera recta (left) and at sphaera obliqua (right).

The completeness of Ptolemy’s analysis of the astronomical consequences of this case can be seen from his remark that it can nevertheless happen that

one observes the same lengths of day and night at sphaera obliqua. But in this case that will occur not at the true equinoctial date when the solar declination

but at some other date (see Fig. 5.11)!

but at some other date (see Fig. 5.11)!

but at some other date with some other Sun’s declination

but at some other date with some other Sun’s declination

.

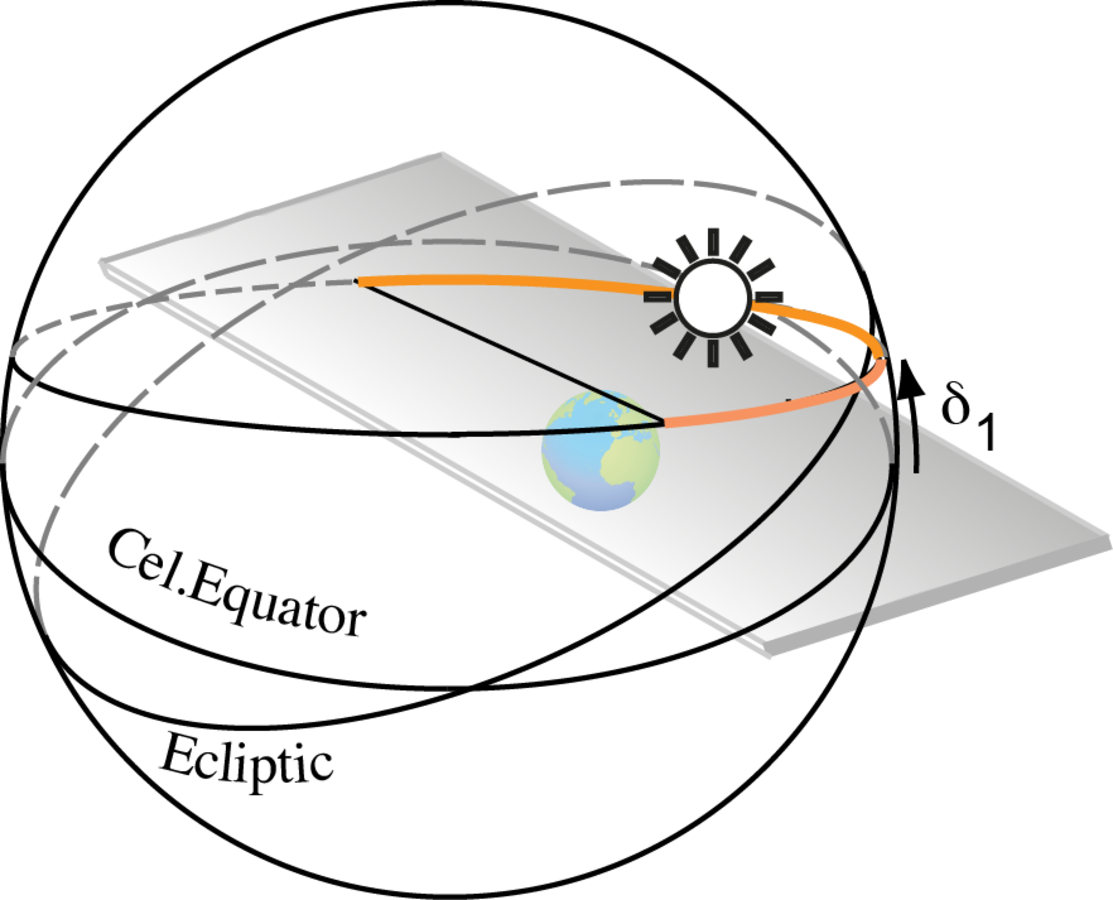

.Fig. 5.11: ‘False equinox’: the Earth is not on the rotational axis of the universe but equidistant from both poles. One can possibly observe the same length of day and night not at the true equinoctial date

but at some other date with some other Sun’s declination

but at some other date with some other Sun’s declination

.

.

The next step in Ptolemy’s analysis is to consider the observational consequences of the Earth’s displacement to the east or to the west. He proposes the following counter-arguments:51

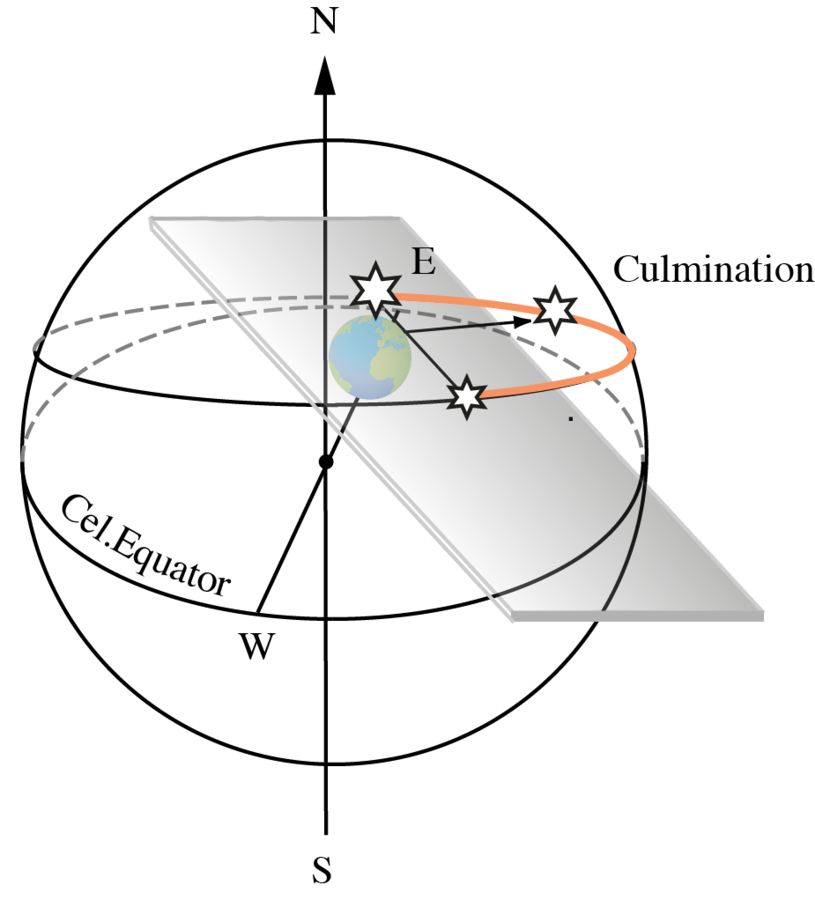

The sizes and distances of the stars

The time-interval from rising to culmination would not be equal to the interval from culmination to setting (see Fig. 5.12).

Fig. 5.12: Displacement in the eastern direction. Stars appear to be bigger in the eastern direction and smaller in the western direction. The peak moment does not lie in the middle of the time-interval between the rising and setting of stars.

Fig. 5.13: Displacement in the eastern direction. The angular distances between the stars

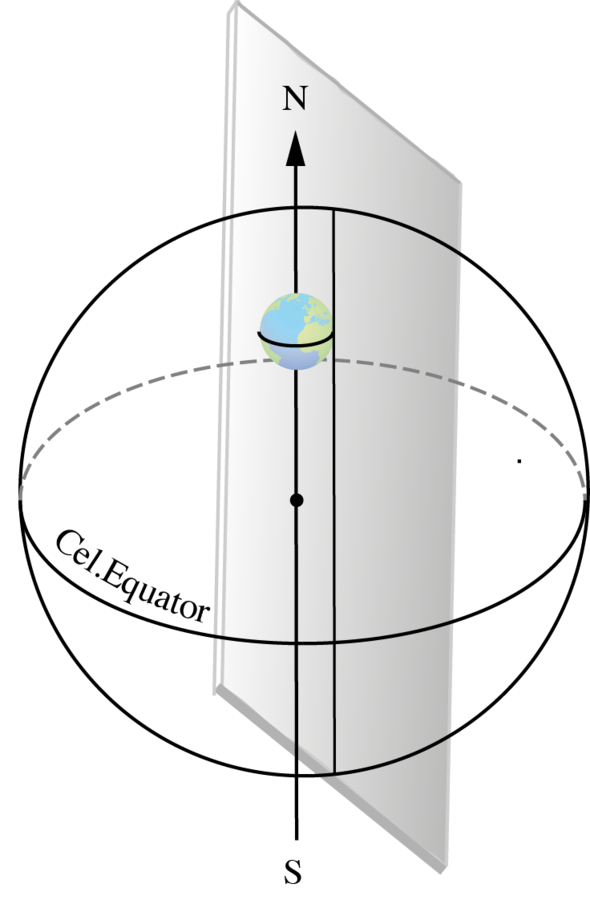

Having considered and ruled out the possible symmetrical displacement of the Earth from the rotational axis of the universe, Ptolemy begins to consider the astronomical consequences of the possible displacement of the Earth in the north-south direction along the rotational axis. He concludes that in this case:52

The plane of the horizon would divide the heavens into unequal parts, different for different latitudes.

The plane of the ecliptic would also be divided by the plane of the horizon into unequal parts; instead the six zodiacal signs are visible above the Earth at all times and places

Only at sphaera recta could the horizon bisect the celestial sphere.

The shadow of the gnomon

Fig. 5.14: Displacement of the Earth along the rotational axis of the universe: the plane of the horizon would divide the heavens into unequal parts, varying for different latitudes.

Fig. 5.15: Displacement of the Earth along the rotational axis of the universe: Only at sphaera recta could the horizon bisect the celestial sphere.

The last (fourth) argument in the list is of special interest:

[…] if the Earth were not situated exactly below the [celestial] equator, but were removed towards the north or south in the direction of one of the poles, the result would be that at the equinoxes the shadow of the gnomon

Actually, this is old ‘evidence’ for geocentricism, which was also used as a proof by Pliny in his Natural History:53

It is demonstrated by dioptra, which affords the most decisive confirmation of the fact, that unless the Earth was in the middle, the days and nights could not be equal; for, at the time of the equinox, the rising and setting of the Sun, are seen on the same line, and the rising of the Sun, at the summer solstice, is on the same line with its setting at the winter solstice; but this could not happen if the Earth was not situated in the centre.

A visualization of the above-mentioned argument for the case of the equinox in Pliny is given in Fig. 5.16.

Fig. 5.16: Pliny’s argument: at equinoxes the sunrise and sunset points can be observed along the same line with a dioptra; therefore, the observer is located at the intersection of two great circles, i.e., one is placed in the middle of the universe.

A similar line of argumentation can be found in Euclid

Let Cancer, at point

in the east, be observed through a dioptra placed at point

in the east, be observed through a dioptra placed at point

, and then through the same dioptra Capricorn will be observed in the west at point

, and then through the same dioptra Capricorn will be observed in the west at point

. Since points

. Since points

are all observed through the dioptra, the line

are all observed through the dioptra, the line

is straight.

is straight.

It should be noted that Cancer and Capricorn as zodiacal signs are not observable as points on the celestial sphere; on the other hand, the position of the Sun at the summer solstice is marked by its entrance into the tropic of Cancer and the longitudinal difference between the two signs is equal to

degrees. That means that Pliny’s argument can simply be a reformulation of the ‘mental observation’55 illustrated by Euclid

degrees. That means that Pliny’s argument can simply be a reformulation of the ‘mental observation’55 illustrated by Euclid

The final reason for the central position of the Earth comes from the observation of the Moon’s eclipses:57

Furthermore, eclipses of the Moon would not be restricted to situations where the Moon is diametrically opposite the Sun (whatever part of the heaven [the luminaries are in]),58 since the Earth would often come between them when they are not diametrically opposite, but at intervals of less than a semi-circle.

Ptolemy does not discuss this argument in detail: in fact, it presupposes that both the Sun and the Moon rotate in circular motion around the center of the cosmos. This is certainly not the case for the more elaborate lunar and solar theories developed in the Almagest

The Earth has the ratio of a point to the heavens

One should emphasize that Ptolemy’s statements considered above are practically all valid only if one neglects the Earth’s size in comparison to the size of the universe. His continual repetition of the word sensibly clearly indicates that he himself was aware of the intrinsic precision of his ‘proofs’. The arguments presented in this section should in fact give the necessary justification of the approximation used in the ‘proofs’ of the previous sections. The following arguments are proposed:59

“the sizes and the distances of the stars

“the gnomons

“the planes drawn through the observer’s lines of sight at any point, which we call ‘horizons’, always bisect the whole heavenly sphere.”

The very nature of astronomical observations, however, limits the precision of these arguments to a perceptible level – a fact which was not lost on Ptolemy. Once more, he has to repeat that “the Earth has, to the senses, the ratio of a point to the distance of the sphere of the so-called fixed stars.”60

What is now missing are the arguments which could rule out the displacements relative to the center of the universe which were of the Earth’s size. Such displacements would not be observable with the precision of naked-eye astronomy but could be monitored in frames of Aristotle’s physics

The Earth does not have any motion from place to place

As we have seen, Ptolemy thinks that geocentrism can be sufficiently demonstrated through astronomical considerations based on geometry and observation up to a perceptible level.

Nevertheless, he does not use the physical arguments against the motion of the Earth in Almagest

One can show by the same arguments [provided in support of the centrality of the Earth] that the Earth cannot have any motion in the aforementioned directions, or even move at all from its position at the center. […] Hence I think it is idle to seek for causes for the motion of objects toward the center, once it has been so clearly established from the actual phenomena that the Earth occupies the middle place in the universe, and that the heavy objects are carried toward the Earth.

Ptolemy, exactly like Aristotle (see Fig. 5.2, right) observes that the fall of heavy bodies toward the center is evident since62 “the direction and path of the motion […] of all bodies possessing weight is always and everywhere at right angles to the rigid plane drawn tangent to the point of impact.” Additionally, Ptolemy reviews a series of physical considerations which he perhaps derived from De caelo

[…] although there is perhaps nothing in the celestial phenomena which would count against that hypothesis, at least from simpler considerations, nevertheless from what would occur here on Earth and in the air, one can see that such a notion is quite ridiculous.

As we have seen, Aristotle

Ptolemy’s arguments against the axial rotation of the Earth (and terrestrial motion in general) became famous after Copernicus’s

5.4 Conclusions and prospects

In the Almagest

Still, to account for these divergent approaches to geocentricism, the classical distinction between mathematical and physical astronomy is not sufficient. Averroes

This separation was still at work in the homocentric cosmologies of the early sixteenth century, as was the case with the Italian Aristotelians

From our analysis it has become clear, however, that Ptolemy’s and Aristotle’s arguments for geocentrism cannot be traced back to the separation between abstract mathematical models and real physical causes (Averroism and scholastic philosophy) nor to the separation of computation and explanation (Osiander

Concerning Ptolemy’s

With regard to virtuous conduct in practical actions and character, this science, above all things, could make men see clearly; from the constancy, order, symmetry and calm which are associated with the divine, it makes its followers lovers of this divine beauty, accustoming them and reforming their natures, as it were, to a similar spiritual state.

A cosmological perspective like that of Ptolemy

The “Aristotelian-Ptolemaic system”

Although the commentators of Aristotle, especially through Averroes

In fact, not only have we often received a crystallized image of Greek knowledge, but we have also relied on works which are themselves great syntheses that overshadow and hide previous debates and multiple viewpoints. Just as Aristotle’s

Bibliography

Aristotle (1986). On the Heavens. Aristotle in twenty-three volumes. Loeb classical library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Barker, Peter and Bernard R. Goldstein (1998). Realism and Instrumentalism in Sixteenth Century Astronomy: A Reappraisal. Perspectives on Science 6(3):232–258.

Beere, Jonathan B. (2003). Counting the Unmoved Movers: Astronomy and Explanation in Aristotle’s ‘Metaphysics’ XII.8. Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie 85:1–20.

al-Bitruji (1952). De motibus celorum. Ed. by Francis J. Carmody. Berkeley: University of California press.

Cassirer, Ernst (1927). Individuum und Kosmos in der Philosophie der Renaissance. Leipzig: Teubner.

Cleary, John J. (1996). Mathematics and Cosmology in Aristotle's Philosophical Development. In: Aristotle's Philosophical Development: Problems and Prospects. Ed. by William Wians. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 193–228.

Di Bono, Mario (1990). Le sfere omocentriche di Giovan Battista Amico nell'astronomia del Cinquecento. Genova: Consiglio nazionale delle ricerche, Centro di studio sulla storia della tecnica.

– (1995). Copernicus, Amico, Fracastoro and Tusi's Device: Observations on the Use and Transmission of a Model. Journal for the History of Astronomy 26.

Dijksterhuis, E. J. (1986). The Mechanization of the World Picture. Pythagoras to Newton. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Duhem, Pierre (1969). To Save the Phenomena: An Essay on the Idea of Physical Theory from Plato to Galileo. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Goldstein, Bernard R. (1997). Saving the Phenomena: The Background to Ptolemy's Planetary Theory. Journal for the History of Astronomy 28:1–12.

Granada, Miguel Angel and Dario Tessicini (2005). Copernicus and Fracastoro: The dedicatory letters to Pope Paul III, the history of astronomy, and the quest for patronage. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 36(431-476).

Heglmeier, Friedrich (1996). Die griechische Astronomie zur Zeit des Aristoteles: Ein neuer Ansatz zu den Sphärenmodellen des Eudoxos und des Kallippos. Antike Naturwissenschaft und ihrer Rezeption 6:51–71.

Jori, Alberto (2009). Erläuterung. In: Über den Himmel. Aristoteles: Werke in deutscher Übersetzung 12. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Kouremenos, Theokritos (2010). Heavenly Stuff: The constitution of the celestial objects and the theory of homocentric spheres in Aristotle's cosmology. Stuttgart: Steiner.

Koyré, Alexandre (1978). Galileo Studies. Atlantic Highlands: Humanities Press.

Lerner, Michel-Pierre (2008). Le monde des sphères, Vol.1: Genèse et triomphe d'une représentation cosmique. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

Lloyd, Geoffrey Ernest Richard (1991). Greek Cosmologies. In: Methods and Problems in Greek Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 141–163.

– (2000). ‘Metaphysics’ Λ 8. In: Aristotle's ‘Metaphysics’ Lambda. Ed. by Michael Frede and David Charles. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 245–273.

Moraux, Paul (1949). Einige Bemerkungen über den Aufbau von Aristoteles' Schrift 'De caelo'. Museum Helveticum 6:157–165.

– (1961). La méthode d'Aristote dans l'étude du ciel 'De Caelo' I 1 - II,12. In: Aristote et les problèmes de méthode. Louvain: Publications universitaires.

Omodeo, Pietro Daniel (2014). Copernicus in the Cultural Debates of the Renaissance: Reception, legacy, transformation. Leiden: Brill.

Panti, Cecilia (2001). Moti, virtù e motori celesti nella cosmologia di Roberto Grossatesta: Studio ed edizione dei trattati ‘De sphera,’ ‘De cometis,’ ‘De motu supercelestium’. Firenze: SISMEL, Ed. del Galluzzo.

Pedersen, Olaf (1974). A Survey of the 'Almagest'. Odense: Odense Press.

Ptolemy (1984). Ptolemy's Almagest. Ed. by Gerald J. Toomer. London: Duckworth.

Reinhold, Erasmus (1551). Prutenicae tabulae coelestium motuum. Tubingae: per Ulricum Morhardum.

Rheticus, Georg Joachim (1959). Narratio prima. In: Three Copernican Treatises. Ed. by Edward Rosen. New York: Dover.

Schiaparelli, G. V. (1875). Le sfere omocentriche di Eudosso, di Calippo e di Aristotele. Pubblicazione del Reale Osservatorio di Brera in Milano 9.

Thorndike, Lynn (1949). The ‘Sphere’ of Sacrobosco and Its Commentators. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Footnotes

The standard reference for this issue is Duhem 1969, although the author’s attempt to interpret the history of physics and astronomy from the perspective of twentieth-century epistemology (in particular conventionalism) is completely outdated. For some criticism of Duhem’s anachronism see for instance Barker and Goldstein 1998. In another paper, Goldstein has convincingly argued that “saving the phenomena” in antiquity, and according to Ptolemy in particular, did not mean limiting astronomical consideration to computational hypotheses as merely conventional. Quite the opposite: it often meant “to seek an underlying orderly reality that can explain the disorderly appearances that are a kind of illusion,” as was the case with Geminus. In the case of Ptolemy, moreover, “the phenomena are ‘real’ and not illusions, for they are the criteria by which the models are judged, not the other way round” (Goldstein 1997, 8).

The classic treatment of this issue is Schiaparelli 1875. For a reassessment, see Heglmeier 1996.

Theokritos Kouremenos has recently argued against Aristotle’s adherence to a homocentric world system of concentric material spheres as the real physical structure of the world (Kouremenos 2010). Be that as it may, relative to the original intentions of Aristotle, the Eudoxan interpretation of his cosmology on the basis of Metaphyisics XII has largely prevailed at least from the Middle Ages onwards. For a discussion of Metaphyisics XII,8, see Beere 2003. See also Lloyd 2000.

See F.J. Carmody’s Introduction to al-Bitruji 1952, in particular Chapter Three “Al-Bitruji in Western Europe, 1217–1531” (pp. 44–38).

Cf. Panti 2001.

Cf. Lloyd 1991, 146: “cosmology in the strictest and fullest sense […]: by the strictest sense I mean a comprehensive view of the cosmos as an ordered whole.”

Reinhold 1551, “Logistice scrupulorum astronomicorum”, f. 1v. For a discussion on this matter, see Omodeo 2014, 104–106.

See Jori 2009, 123.

Moraux 1949, 159: “Wenn wir einige durch Ideenassoziationen eingeleitete Abschweifungen beiseitelassen, so können wir behaupten, daß dieser gut abgewogene Plan die strukturelle Einheit der Bücher A und B beweist. Allem Anschein nach wurden diese Bücher als ein selbständiges Ganzes konzipiert: Ein Zeichen dafür ist, daß die Abhandlung über die Erde (B 13–14) als der letzte Punkt angekündigt wird, der zu besprechen ist, um das vorgesehene Programm abzuschließen.”

De caelo II,13 293 a 19–21. In the following we shall quote from the English translation by Guthrie, Aristotle 1986.

De caelo II,13 293 b 25–30.

De caelo II,13 294 a 11 ff.

De caelo II,13 294 b 32–295 a 2.

Cf. Moraux 1961, 182, n. 10: “Il serait trop long de relever tous les cas où, dans l’étude de l’univers et du ciel, il est fait état des principes de la physique terrestre. Voici pourtant quelques exemples intéressants. Théorie des quatre éléments, des mouvements et des lieux naturels […]. Théorie de la pesanteur et lois mécaniques de la chute des corps […]. Théorie de la génération et de la corruption. Opposition du ‘selon nature’ et ‘contre nature’ ou ‘par violence’. Hylémorphisme […]. Existence de détérminations telles que devant-derriére, droite-gauche, etc., chez les animaux […].”

De caelo I,13 294 a 17–19.

De caelo II,13 295 a 13 ff.

De caelo II,13 295 b 3–9.

De caelo II,13 295 b 10 ff.

De caelo II, 13 295 b 23–25.

De caelo II, 14 296 a 24–25.

De caelo II,14 296 a 25 ff.

De caelo II,14 296 a 34 ff.

De caelo II, 14 296 a 35 – 296 b 6.

De caelo II,14 296 b 6 ff.

De caelo II, 14 296 b 15–16.

De caelo II, 14 296 b 22–25.

De caelo II,14 b 25 ff.

De caelo II, 14 297 a 2–8.

Almagest I H6, p. 46. Here and in the following we will quote from the English translation by Toomer, Ptolemy 1984.

Almagest I H9, p. 48.

In the second book of his Planetary hypotheses, where Ptolemy extends the mathematical models of the Almagest to the physical realm, stars are thought to be fixed not on the spherical shell, but rather between nested spherical shells.

Almagest I H10, p. 48.

Although intuitively clear, these arguments really need some mathematical justification, namely that the intersection between a plane and a sphere is always a circle.

Meteorologica, II, VI, 363 b.

Almagest I H11, p. 48.

The authors would like to thank H. Mendell for a thorough discussion on the cylindrical model in relation to Anaximander.

Aetius II 24.9: “The same philosopher [Xenophanes] maintains that the Sun goes forward ad infinitum, and that it only appears to revolve in a circle owing to its distance.”

Almagest I H11, pp. 48–39.

This explanation is actually incorrect; in his later work (Optics, III 60) this phenomenon, now known as a Ponzo-illusion, is correctly explained as a pure psychological effect.

Aetius II I3, I4, III 2.II: “According to Xenophanes the stars are made of clouds set on fire; they are extinguished each day and are kindled at night like coals, and these happenings constitute their settings and rising respectively.”

Almagest I 3 H12, p. 49.

Almagest I H13, pp. 49–40.

According to Toomer (Ptolemy 1984, 41), these propositions were proved in a work by Zenodorus as early as the second century BCE.

See, for example, D.R. Dicks Early Greek Astronomy to Aristotle, p. 166: “The data are very inaccurate for the latitude of Babylon (particularly the equinoctial and winter solstitial figures), which is not surprising since the underlying assumption seems to be that the length of the shadow increases in arithmetical progression with the height of the Sun […]. Moreover, the results are set out according to a predetermined scheme whereby the solstices and equinoxes are placed arbitrarily on the 15th day of the first, fourth, seventh, and tenth months of a schematic year of twelve months and thirty days each.”

Strictly speaking, the eastern and western directions are defined locally for every observer relative to the local northern direction; for further considerations we will also use a global coordinate system with a northern direction defined through the rotational axis of the cosmos and an east-west direction coinciding with the intersection line between the ecliptic and equatorial plane.

Almagest I H17, p. 41.

Here, Ptolemy explicitly implies that the Earth’s size is negligible in comparison to the distance to the stars; otherwise the Earth would not be equidistant from both poles.

Almagest I H18, p. 42.

Almagest I H18–19, p. 42.

Pliny, Natural History I, Chapter 70.

Euclid, Phaenomena I.

To our knowledge, this kind of observation was, in fact, never made: not only the atmospheric refraction but also a final size of the Sun would make the precision of such ‘proofs’ mathematically invalid.

Almagest I H19, p. 42.

Almagest I H19, p. 42.

That is, at opposition, at full Moon.

Almagest I H21, p. 43.

We can only agree here with Toomer’s comment that the classification ‘so-called’ used for the fixed stars means that for Ptolemy the stars did in fact have a motion – that is, precession.

Almagest I,7 p. 43.

Almagest I, 7 p. 43.

De caelo II, 13.

Almagest I, 7 p. 43.

Almagest I, 7 p. 44.

Ibid.

Almagest H25, p. 45.

We do not agree with Pedersen’s manner of comparing Aristotle’s and Ptolemy’s physics (Pedersen 1974, 43–45). On the one hand, Pedersen uncritically assumes the Aristotelian background of Ptolemy. On the other hand, he interprets Almagest I, 7 anachronistically and extrinsically, using expressions like “an immense pressure of the ether molecules.” On top of this, Pedersen does not distinguish in his discussion between the theory of the central Earth turning about its axis and the heliocentric system. For a better insight into this issue, see Lerner 2008, 63–81, in which Michel-Pierre Lerner discusses what he calls “la critique sévère du systéme astronomique d’Aristote par Ptolémée.” Ptolemy’s criticism of Aristotle’s natural conceptions mainly concerns the properties of the ether and heavenly bodies. Moreover, he rejects Aristotle’s system of concentric spheres in favor of a model in which eccentric and epicycles are not only mathematical tools abstracted from reality, but have physical existence, as emerges from Planetary hypotheses.

Cf. Cleary 1996, 191: “One of Aristotle’s most significant steps in moving beyond Platonism was to replace mathematics with physics as the cosmological science par excellence. However, this does not mean that he rejected mathematics as a science relevant to cosmology, but rather that he subordinated it to physical inquiry.”

Almagest I, 7.

Notably, Koyré not only emphasized the Copernican dependency of physics on cosmology – of the development of a new dynamics on the heliocentric planetary astronomy – but even (and, in our opinion, unduly) generalized this dependency in order to account for the entire evolution of scientific thought from Copernicus to Newton. Cf. Koyré 1978, 131.

Almagest p. 46.

Almagest p. 46.

Almagest p. 46.

Almagest pp. 46–37.

The classic treatment of the complex relationship between microcosm and infinity is Cassirer 1927.

This pluralism has been clearly stressed, among others, by Lloyd 1991, 151: “There is not such a thing as the cosmological theory, of the Greeks. Indeed, one can and must go further: one of the remarkable features of Greek cosmological thought is that for almost every idea that was put forward, the antithetical view was also proposed.” This is what Lloyd calls the “dialectical” character of Greek science.