14.1 Introduction

It has been commonly the case that while discussing the transmission of the sciences to regions outside Europe there is ample reference to

The history of the transmission of scientific ideas from

The attempts to answer these questions set a new framework for the discussion of the “local” in history of science. How does the “local” integrate into the “universal”? Through which processes were local intellectual and institutional contexts incorporated into the dominant scientific ideal? What was the role of the local cultural traditions in the building of a uniform European scientific culture? Historians dealing with these questions aim at promoting the study of local issues avoiding the pitfalls of the received heroic accounts. They also aim at exchanging information and methodological contemplations in order to examine to what extent the “view from the periphery” might bring a new perspective to the history of science in general.1

In what follows we shall present the development of

14.2 Historical Background

In the eighteenth-century Balkans various social formations started coming into existence as a result of the intricate historical process prompted by the decline of the

Immediately after the fall of the city in 1453, Sultan Mohammed II appointed Georgios Gennadios (ca. 1400–1472) the new Patriarch of the Orthodox Church and provided him with a written “privilege” that granted the Christian authorities jurisdiction over many aspects of the religious and civil life of the Christian populations of the Balkans and Asia Minor. The Sultan’s decision was a highly symbolic gesture aiming to respond to the complications related, on the one hand, to the

One of the most important consequences of this arrangement was that it allowed the Patriarchate to ascertain control over the educational activities of these populations. For a long time, however, education was very poor, since its basic aim was the (re)production of medium rank clergy. According to all (but to be sure, quite limited) extant evidence Psimmenos 1988, 174, the school curricula of the sixteenth century included

The physiognomy of education and the respective features of intellectual life were further defined by the subsequent social developments in the Ottoman Balkans. The early eighteenth century witnessed the emergence of the Phanariots, a group of Greek-speaking noblemen who simultaneously served at the court of the Ecumenical Patriarchate (situated in the Phanari region of Constantinople, hence the name Phanariots) and of the Ottoman

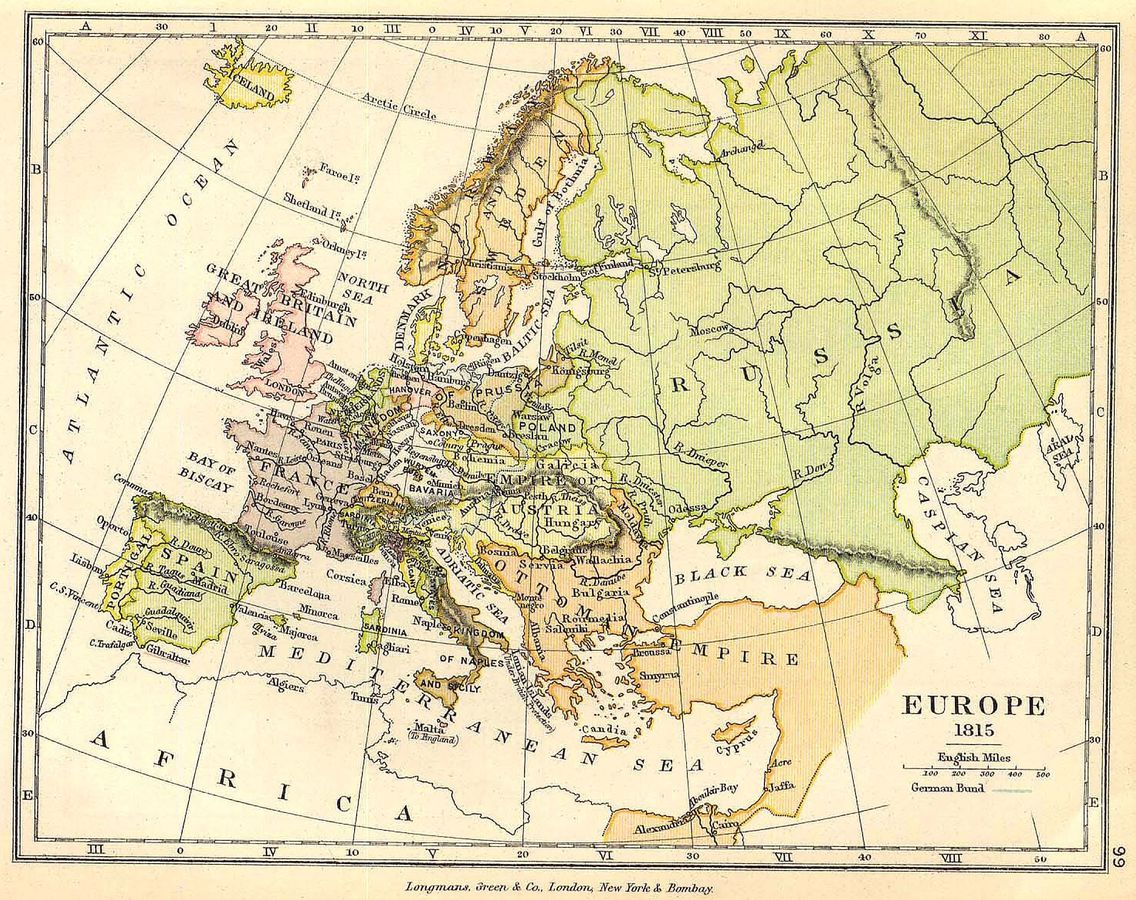

Fig. 14.2: Europe has always been a changing landscape. So too were the flows of knowledge that shaped

At the same time, another social group sought to secure its share in the distribution of social and economic power among the Orthodox populations of the Balkans. It was the group of wealthy craftsmen and merchants of Epirus, western Macedonia and Thessaly. The area had a long tradition in commercial and handicraft activities, but it also comprised the most important

All these developments did not alter, of course, the basic features of educational activities and, most importantly, the predominance of the Church in educational matters. Both Christian faith and Greek-speaking education, the two elements that unified such different groups as the Phanariots of Constantinople, the Vlach merchants of Epirus, the Greek fraternity of Venice, the Greek-speaking immigrants of central Europe and the

From the outset of the eighteenth century, Greek-speaking scholars began to disperse throughout Europe, and Padua ceased to be the almost exclusive place to study. They also began to travel to the German states, the Low Countries, Russia, the

14.3 Newtonianism in the Greek Intellectual Context

The introduction of Newtonian ideas into the Greek intellectual space took place basically in the second half of the eighteenth century. During that period, a great number of

Many eighteenth-century Greek-speaking scholars spent a significant period of time in important European universities. As already mentioned, since the seventeenth century, the dominant tradition was to attend the university of Padua and, to a much lesser extent, other Italian universities. As the decades went by, though, one can observe a shift toward German universities, as well as a turn of the intellectual focus toward German-speaking centers: Vienna, Leipzig, Jena and Halle. In either case, Greek-speaking scholars had the opportunity to be actual witnesses of various discussions and disputes concerning a number of issues in

How is one to assess the receptiveness of Greek intellectual life toward the

One issue that has actually puzzled historians about the intellectual attitude of eighteenth-century scholars is their views on experiment. In the eighteenth century,

Similar things hold concerning the mathematization of

The ambiguous relationship of Greek-speaking scholars with

14.4 Centers and Peripheries

Τhe agenda of most historians who study eighteenth-century Greek intellectual life draws heavily upon the idea of transfer.

The above scheme conveniently served for many years the fields of economic and political theory. Serious problems emerge, however, when it is used as a historiographic scheme. The last thirty years history of science witnessed the emergence of a whole thematic area, which is known as reception studies. The purpose of most works produced in this area has been to examine the spread of the scientific and technological attainments in areas that did not originally participate in the shaping of the respective ideas and practices. The term “reception studies” is often used to denote that there is something (a science, a scientific theory, a technological innovation) which was formed in a certain social and intellectual environment (a center of scientific or technological production) and, thanks to its inherent dynamics (its explanatory efficiency, its emancipating power, its undeniable usefulness), spreads in other environments, very different from the one where it first appeared. A significant number of historical works have been produced according to this model: The spread of the scientific ideas of the Enlightenment in the

The kind of scientific activity that was eventually established in the receiving environment is usually described as the outcome of such confrontations. In many cases the confrontation was resolved either through institutional initiatives—the establishment of academies, universities or laboratories, which accommodated the new scientific activity—or thanks to certain social developments that favored the establishment of the scientific community and the respective interest groups, which took advantage of the new science.9 In other cases, the confrontation spanned a long period of social imbalance and came to an end only thanks to a deep social transformation.10 In almost all cases, however, the stake is the same: The extent to which the particular confrontation favored or inhibited the establishment of a new science or the extent to which it resulted in the distortion of its principles during the transfer from the place of its birth to the receiving environment.

14.5 New Trends in the Historiography of Science

Apparently, these methodological developments set a new ground for the study of

The notion of appropriation is crucial to this approach. The purpose of a

It would thus be interesting to see historians direct their attention less to listing which ideas and theories were successfully transmitted to the local intellectual context, and more to the metamorphoses these ideas underwent through the various stages of assimilation. The specific approach is further justified by the fact that when one refers to the early modern period, the homogeneity of such cognitive enterprises as “Scientific Revolution,” “science,” “physics,” or “Newtonianism” is extremely vague. However, the broad discussion about the

Would it be possible, in light of the above problematique, to develop an alternative interpretation of eighteenth-century Greek scientific thought? And would such an interpretation be of any use to history of science in general? No doubt, Greek-speaking scholars honored the new

Knowledge is the perspicuous understanding of the beings. Partial or individual knowledge results from individual observations or experiments;empirical knowledge results from many such experiments and observations; scientific knowledge, finally, is the knowledge which [on top of these] also includes the reason of the being and can be combined with other such pieces of scientific knowledge.14

Hence, according to this definition, what the moderns did was, at best,

Undoubtedly, the Greek-speaking scholars shared with other European scholars the desire to inaugurate an intellectual enterprise that would meet the current condition of philosophy. The question they faced, though, was not about the acceptance or rejection of a new philosophical system about Nature, but about the way they would revive and broaden the scope of their contemporary philosophy. Some European philosophers took groundbreaking initiatives for setting up the new edifice of philosophy: They conducted experiments aiming to unveil the

Taking this perspective may significantly change our idea about the intellectual attitude of eighteenth-century Greek-speaking scholars toward

14.6 Conclusions

Working on the history of science in the periphery does not mean that one should, primarily, aim to do justice to the unsung heroes of the periphery or to restore the contribution of the peripheral countries to the building of the glorious edifice of modern science. Apparently, an important dimension of the work of historians who deal with local issues relates to the unearthing of unknown sources, and to the discussion of the historical circumstances under which modern science and technology were established in the particular context. At the same time, though, periphery is something more than a historical and geographical demarcation: Periphery is also a historiographic standpoint. For a long time, the standard narrative in history of science and technology used to take the distinction between center and periphery for granted and to focus primarily on the conditions that contributed to the formation of “original” ideas and practices in the centers and, subsequently, on the conditions that boosted or impeded their spread in the peripheries. Recent studies seem to indicate the obsolete character of such approaches and suggest a more detailed investigation into the circumstances that rendered science and technology a global validity. Starting from the periphery—or better, standing on the periphery—might offer a clearer view over the intricate ideological constructs, which accompanied the establishment of science and technology and obscured their socio-political grounding. In many cases, what looked like a complete synthesis when seen from the point of view of the center, was entirely disassembled when it reached the peripheries to become the object of intense philosophical and political consideration.

What did

References

Ahnert, Thomas (2004). Newtonianism in Early Enlightenment Germany, c. 1720 to 1750: Metaphysics and the Critique of Dogmatic Philosophy. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 35(3): 471-491

Basalla, George (1967). The Spread of Western Science. A Three-Stage Model Describes the Introduction of Modern Science into any Non-European Nation. Science 156(3775): 611-622

Baxandall, Michael (1985). Patterns of Intention: On the Historical Explanation of Pictures. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Ben-Zaken, Avner (2004). The Heavens of the Sky and the Heavens of the Heart: The Ottoman Cultural Context for the Introduction of Post-Copernican Astronomy. British Journal for the History of Science 37(1): 1-28

Biagioli, Mario (1993). Galileo, Courtier: The Practice of Science in the Culture of Absolutism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- (1999). The Science Studies Reader. New York: Routledge.

Cerruti, Luigi (1999). Dante's Bones. In: The Sciences in the European Periphery During the Enlightenment Ed. by K. Gavroglu. Archimedes: New Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic 95-178

Cicanci, Olga (1986). Le rôle de Vienne dans les rapports économiques et culturels du Sud-Est européens avec le centre de l'Europe. Revue des études sud-est européene 24: 3-16

Cohen, H. Floris (1994). The Scientific Revolution: A Historiographical Inquiry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cohen, I.Bernard, Anne Whitman (1999). Isaac Newton, The Principia. Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. A New Translation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Cueto, Marcos (1989). Andean Biology in Peru: Scientific Styles on the Periphery. ISIS 80(4): 640-658

Cunningham, Andrew, Perry Williams (1993). De-Centring the “Big Picture”: The “Origins of Modern Science” and the Modern Origins of Science. British Journal for the History of Science 26(4): 407-432

Despicht, Nigel (1980). “Center” and “Periphery” in Europe. In: European Studies in Development: New Trends in European Development Studies Ed. by J. De Bandt, P. Mandi, P. M.. London: Macmillan 38-41

Fara, Patricia (2002). Newton: The Making of Genius. London: Macmillan.

Gavroglu, K., M. Patiniotis, M. P., Papanelopoulou M., P. M., F. Papanelopoulou, F. P., Simões F., S. F. (2008). Science and Technology in the European Periphery: Some Historiographical Reflections. History of Science 46(2): 153-175

Gavroglu, Kostas (1995). Οι Επιστήμες στον Νεοελληνικό Διαφωτισμό και Προβλήματα Ερμηνείας τους [The Sciences During the Neohellenic Enlightenment and Problems of their Interpretation]. Νεύσις 3: 75-86

Gavroglu, Kostas, Manolis Patiniotis (2003). Patterns of Appropriation in the Greek Intellectual Life of the 18th Century: Α Case Study on the Notion of Time. In: Revisiting the Foundations of Relativistic Physics: Festschrift in Honor of John Stachel Ed. by A. Ashtekar, R. Cohen, R. C., Howard R., H. R., D. Howard. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic 569-592

Gazis, Anthimos (1799). Γραμματική των Φιλοσοφικών Επιστημών [Grammar of the Philosophical Sciences]. 2 vols. Vienna.

Goodman, David C. (1988). Power and Penury: Government, Technology and Science in Phillip II's Spain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hard, Mikael, Andrew Jamison (1998). The Intellectual Appropriation of Technology: Discourses on Modernity, 1900–1939. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Henderson, George Patrick (1970). The Revival of Greek Thought 1620–1830. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Henry, John (2002). The Scientific Revolution and the Origins of Modern Science. Houndmills: Palgrave.

Hering, Gunnar (1968). Ökumenisches Patriarchat und Europäische Politik, 1620–1638. Wiesbaden: Steiner.

Ihsanoğlu, Ekmeleddin (2004). Science, Technology and Learning in the Ottoman Empire: Western Influence, Local Institutions, and the Transfer of Knowledge. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate, Variorum.

Karas, G., G. Vlachakis, G. V., Karamperopoulos G., K. G., D. Karamperopoulos, D. K., Kastanis D., K. D., N. Kastanis, N. K. (2003). Ιστορία και Φιλοσοφία των Επιστημών στον Ελληνικό Χώρο (17 ος–19 ος αι.) [History and Philosophy of the Sciences in the Greek Space (17th–19th c.)]. Athens: Μεταίχμιο.

Karas, Giannis (1991). Οι Θετικές Επιστήμες στον Ελληνικό Χώρο (15 ος–19 ος Αιώνας) [Positive Sciences in the Greek Space (15th–19th c.)]. Athens: Δαίδαλος, Ι. Ζαχαρόπουλος.

Kodrikas, Panagiotis (1794). Oμιλίαι περί Πληθύος Kόσμων [On the Plurality of Worlds]. Vienna.

Kondylis, Panagiotis (1988). Ο Νεοελληνικός Διαφωτισμός: Οι Φιλοσοφικές Ιδέες [Neo-Hellenic Enlightenment: The Philosophical Ideas]. Athens: Θεμέλιο.

Konstantas, Gregorios (1804). Στοιχεία της Λογικής, Μεταφυσικής και Ηθικής [Elements of Logic, Metaphysics and Ethics]. 4 vols. Venice.

Koumas, Konstantinos (1807). None. 8 vols. Vienna.

Lértora Mendoza, C. A., E. Nicolaidis, E. N. (2000). The Spread of the Scientific Revolution to the European Periphery, Latin America and East Asia. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols Publishers.

Lindqvist, Svante (1993). Center on the Periphery: Historical Aspects of Twentieth-Century Swedish Physics. Canton, MA: Science History Publications.

Makraeos, Sergios (1797). Tρόπαιον εκ της Eλλαδικής Πανοπλίας κατά των Οπαδών του Κοπερνίκου [A Triumph of Greek Armaments against Copernicus' Followers]. Vienna.

- (1816). Eπιτομή Φυσικής Ακροάσεως [Compendium of Physics]. Venice.

Mazower, Mark (2000). The Balkans. London: WeidenfeldNicolson.

Mazzotti, Massimo (1998). The Geometers of God: Mathematics and Reaction in the Kingdom of Naples. ISIS 89(4): 674-701

Misa, Thomas J., Johan Schot (2005). Inventing Europe: Technology and the Hidden Integration of Europe. History and Technology 21(1): 1-19

Nieto-Galan, Augusti (1999). The Images of Science in Modern Spain: Rethinking the “Polémica”. In: The Sciences in the European Periphery During the Enlightenment Ed. by Kostas Gavroglu. Archimedes: New Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic 73-94

Patiniotis, Manolis (2003). Scientific Travels of the Greek Scholars in the 18th Century. In: Travels of Learning. A Geography of Science in Europe Ed. by A. Simões, A. Carneiro, A. C.. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers 47-75

- (2005). Newtonianism. In: Machiavellism to Phrenology Ed. by Maryanne Cline Horowitz. New Dictionary of the History of Ideas. Detroit, Mich.: Charles Scribner's Sons 1632-1638

- (2006). [Book review] Ekmeleddin Ihsanoğlu, . Nuncius 21: 435-436

- (2007). Periphery Reassessed: Eugenios Voulgaris Converses with Isaac Newton. British Journal for the History of Science 40(4): 471-490

Philippidis, Daniel (1803). Eπιτομή Aστρονομίας [Compendium of Astronomy]. 2 vols. Vienna.

Polanco, Xavier (1989). Naissance et développement de la Science-Monde: Production et reproduction des communautés scientifiques en Europe et en Amérique Latine. Paris: Editions de la Découverte/Conseil de l'Europe/UNESCO.

Psimmenos, Nikos (1988). Η Ελληνική Φιλοσοφία από το 1453 ως το 1821, Vol. 1, Η Κυριαρχία του Αριστοτελισμού [Greek Philosophy from 1453 to 1821, Vol. 1, The Predominance of Aristotelianism]. Athens: Γνώση.

Ragep, F. Jamil, Sally P. Ragep, S.P. R. (1996). Tradition, Transmission, Transformation: Proceedings of Two Conferences on Pre-Modern Science Held at the University of Oklahoma. Leiden: Brill.

Rieber, Alfred J. (1995). Politics and Technology in Eighteenth-Century Russia. Science in Context 8(2): 341-368

Rigas, Velestinlis (1790). Φυσικής Απάνθισμα [Florilegium of Physics]. Vienna.

Rupke, Nicolaas (2000). Translation Studies in the History of Science: The Example of “Vestiges”. British Journal for the History of Science 33(2): 209-222

Santesmases, Maria Jesús, Emilio Muñoz (1997). The Scientific Periphery in Spain: The Establishment of a Biomedical Discipline at the Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas, 1956-1967. Minerva 35(1): 27-45

Schaffer, Simon (1989). Glass Works: Newton's Prisms and the Uses of Experiment. In: The Uses of Experiment. Studies in the Natural Sciences Ed. by D. Gooding, T. Pinch, T. P.. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 67-104

Schmitt, Charles B. (1984). Aristotelianism in the Veneto and the Origins of Modern Science: Some Considerations on the Problem of Continuity. In: The Aristotelian Tradition and Renaissance Universities Ed. by Charles B. Schmitt. London: Variorum Reprints 104-123

Schot, Johan, Thomas J. Misa, T.J. M. (2005). Tensions of Europe: The Role of Technology in the Making of Europe..

Selwyn, Percy (1979). Some Thoughts on Cores and Peripheries. In: Underdeveloped Europe: Studies in Core-Periphery Relations Ed. by D. Seers, B. Schaffer, B. S.. Harvester Studies in Development. Hassocks: Harvester Press 37-39

Shapin, Steven, Simon Schaffer (1985). Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle and the Experimental Life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Simões, Ana, Ana Carneiro, A. C. (1999). Constructing Knowledge: Eighteenth-Century Portugal and the New Sciences. In: The Sciences in the European Periphery During the Enlightenment Ed. by K. Gavroglu. Archimedes: New Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic 1-40

Stoianovich, Traian (1960). The Conquering Balkan Orthodox Merchant. Journal of Economic History 20(1): 234-313

Theotokis, Nikiforos (1766). Στοιχεία Φυσικής [Elements of Physics]. Leipzig.

- (1767). Στοιχεία Φυσικής [Elements of Physics]. Leipzig.

Todd, Jan (1993). Science at the Periphery: An Interpretation of Australian Scientific and Technological Dependency and Development prior to 1914. Annals of Science 50(1): 33-58

Tsourkas, Cléobule (1967). Les débuts de l'enseignement philosophique et la libre pensée dans les Balkans: La vie et l'oeuvre de Théophile Corydalée (1570–1646). Thessaloniki: Institute for Balkan Studies.

Vlachakis, Giorgo (1996). Η νευτώνεια Φυσική και η Διάδοσή της στον Ευρύτερο Βαλκανικό Χώρο [Newtonian Physics and its Spread in the Broader Balkan Space]. Athens: Τροχαλία.

Voulgaris, Eugenios (1805a). Tα Aρέσκοντα τοις Φιλοσόφοις [Philosophers' Favorites]. Vienna.

- (1805b). Στοιχεία της Μεταφυσικής [Elements of Metaphysics], 3 parts. Venice.

Wright, David (1996). John Fryer and the Shanghai Polytechnic: Making Space for Science in Nineteenth-Century China. British Journal for the History of Science 29(1): 1-16

Footnotes

Such recent undertakings are STEP (“Science and Technology in the European Periphery”) and the “Tensions of Europe.” The former is a group of historians of science from many European countries (Belgium, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Russia, Turkey, Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Hungary) who study the circulation of scientific knowledge between European centers and peripheries from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. See http://www.uoa.gr/step and Gavroglu et.al. 2008 for a historiographic review. “Tensions of Europe” is a network of historians from seventeen countries who explore transnational European history with a focus on the roles of technology as forces of change. Their main tenet is that examining the European integration through the lens of technology will make visible a bottom-up “hidden integration” and provide a deeper and richer historical understanding of the process. See http://www.tensionsofeurope.eu. Concerning the scope and the historiographic perspective of the group, see Misa and Schot 2005; Schot et.al. 2005.

The unique exception is the two polemical books written by Sergios Makraeos, one criticizing the introduction of the heliocentric system Makraeos 1797 and the other—twenty years later—attempting to restore Aristotelian physics Makraeos 1816. Interestingly enough, the former employs a certain interpretation of the Newtonian concept of central forces in order to prove the instability of the heliocentric system.

Especially Optics. See, for example, Voulgaris 1805b, part 2, 155; Voulgaris 1805a, 38–41

Indicatively: Kondylis 1988; Vlachakis 1996; Karas et.al. 2003.

See, however Schaffer 1989.

See the introduction in Henderson 1970.

This was, for example, the case of Coimbra University and of the Royal Academy of Science in eighteenth-century Portugal Simões et.al. 1999, of the scientific and educational reforms of Peter the Great in eighteenth-century Russia Rieber 1995, and of the Shanghai Polytechnic School, established in the second half of the nineteenth century Wright 1996.

This is to some extent the case of late eighteenth-century Spain (for the diverse views over this period, see Nieto-Galan 1999) and of nineteenth-century Italy Cerruti 1999. Also of special interest to our analysis is the case of the Ottoman Empire, which first came into contact with the Western sciences at the beginning of a long social transformation, which started in the mid-eighteenth century and culminated with the movement of Tanzimat, between 1839 and 1856. On this issue, see Ihsanoğlu 2004 and its review Patiniotis 2006.

Probably the most influential study of this historiographic trend is Shapin and Schaffer 1985. See also Biagioli 1993. The respective bibliography is quite extensive and displays many differentiations. For a comprehensive overview see, among others Biagioli 1999.

See, for example, Cunningham and Williams 1993; Cohen 1994; Henry 2002. On the multiplicity and the diversity of interpretations making up the eighteenth-century European image of Newtonianism, see Patiniotis 2005. For the great variety of social, cultural and symbolic uses of the Newtonian heritage, see Fara 2002.

Karas et.al. 2003, 77; translation and emphasis are the authors’ own.