5.1 Introduction

Among the means of

In the context of this paper some of the effects and consequences of notational systems as

Since the beginning of the Neolithic the vast landmass situated at the intersection of Africa, Asia and Europe has seen important cultural

Initially this system reproduced with a limited set of signs clusters of information, namely the primary significant of the message (not the actual speech-act) to be conveyed. Over time it underwent a process of controlled intrinsic (internal) extension and modification, aimed at adapting the tool to the ever-changing needs of different cultures and societies. Parameters such as ergonomics, the avoidance of ambiguity and velocity, among others, must have played an important role in this process. Whereas these parameters are difficult to assess, another parameter’s consequences were more straightforward:

5.2 Writing, Language, and Kulturtechnik

Within Mediterranean antiquity and even beyond, two more-or-less opposed attitudes toward writing and

Another assumption, which has had a strong influence on the analytic perspective adopted in most investigations of writing, is the idea that

These three ways of writing [i.e.logographic, syllabic, alphabetic, ECK] correspond almost exactly to three different stages according to which one can consider men gathered into nation. The depicting of objects is appropriate to a savage people; signs of words and of propositions, to a barbaric people, and the alphabet to civilized people. Rousseau 1966, 17

The claimed relation between

Meanwhile the rather limited perception of writing as a system confined to the encoding of phonological strings14 is intensively discussed and a significantly broader perspective on the relation(s) between speech and writing has been developed. The rather narrow analytical framework of earlier investigations, focusing mainly on encoding (rather than decoding) has been significantly enlarged by shifting focus to the aspect of “reading” as an important, or even the most significant access to the parameters governing writing systems of all kinds Olson 1996. David R. Olson summarizes these outcomes as follows:

First, writing is not the transcription of speech but rather provides a conceptual model for that speech. […] Second, the history of scripts is not, contrary to the common view, the history of failed attempts and partial successes toward theinvention of the alphabet, but rather the by-product of attempts to use a script for a language for which it is ill suited. Third, the models of language provided by our scripts are both what is acquired in the process of learning to read and write and what is employed in thinking about language; writing is in principle metalinguistics.15

I will be returning to the issue of

The perspective that Olson and others have adopted here was reinforced when the semantic range of the term “writing” itself came under discussion. The so-called non-linguistic, second-order aspects have been recognized as central to the operative potential of writing. Consequently language-neutral and iconographic aspects have complemented the language-based concept of writing. Aesthetic and perceptual aspects came into focus. The capability of (any) writing system to record speech more or less adequately is but one perspective to be looked at. In addition to transcribing speech, several other aspects of writing systems can be delineated as follows: (1) The

The overall configuration of these aspects suggests a notion of writing that allows for a multi-perspectival profile, that is, a profile not restricted to the usual interpretation of writing as just another denotationally specified format for the phonological components of

On the contrary, although the discovery of some of its principal elements (representation as the most important) might have occurred accidentally, its constitution as a system is always the consequence of intentional coordination. This holds true not only for de novo scripts, but also for the introduction of (newly invented or existing) scripts within a given society. (Cancik-Kirschbaum and Johnson forthcoming forthcoming)

At the same time writing incorporates a potentially creative force, insofar as it can take on a leading role in the creation or internal development of cultural segments (or subsystems), such as religion, law, politics, economics, and so forth. But one must bear in mind, at the same time, that once writing has determined parts or even the entirety of these social spheres, other traditions will have been transformed, suppressed, or even forgotten. That is to say, the creative process associated with the implementation of a written tradition is inevitably linked to process of selection with regard to the existing repertoire of knowledge.

5.3 Writing and Textuality: Different Levels of Representation of Knowledge

In the Ancient Near East, writing as a means of graphic communication originates within the sphere of bureaucracy and economic

Seals, potters’ marks, painting and craft ornamentation, tokens, bullae, numerical tablets, and other designs – these must be seen as parallelsystems of communication. Michalowski 1990, 59

Multiple technical and conceptual stimuli—some of which certainly elude us—seem to coincide in the formation of a new

Early Mesopotamia and its adjacent regions furnish detailed, although evidence of the pristine establishment of several writing systems. The process of adapting writing systems to particular languages has repeatedly taken place between the third and the first millennium BCE, as various civilizations adopted the

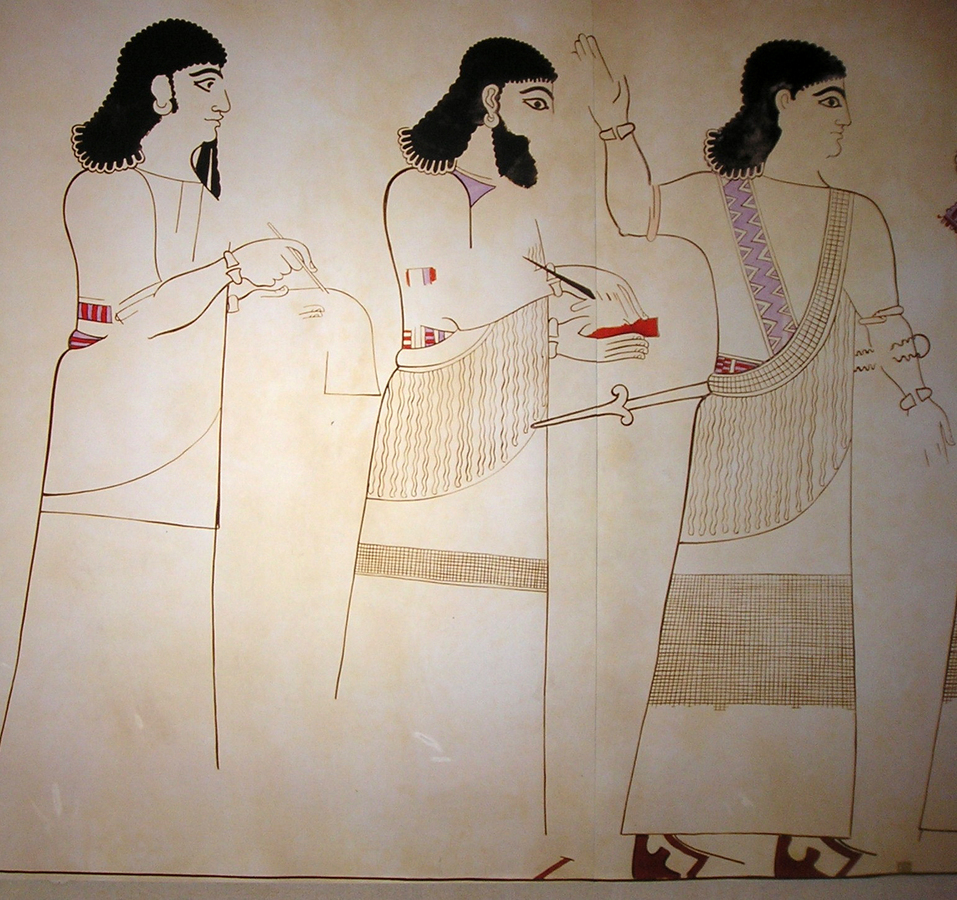

Fig. 5.1: Assyrian scribe writing Akkadian in

The actual history of all these different writing systems—whether cuneiform, linear, or hieroglyphic—can be taken one representation of the globalization of knowledge, namely knowing “how to write.” Indirectly they are linked to

The process of transmission takes on a special nuance if seen within the vital sphere of cultural contact. The transfer of a writing system together with its didactic material on the one hand, and the transformation of the system in order to adapt it to the concrete needs of the receiving community on the other hand, fostered an awareness of linguistics and grammatical thought. These became explicit not only in

Once writing has been installed as a system of recording, following orthographic norms and conventions, the adaptation to the manifold chaos of language and speech-act is obviously achieved by direct usage. As to the incentives that may at first have stimulated this widening of the primary disposition of the recording system one can only speculate. To an important degree, they are based on conditions that have been observed for such processes leading to expanded use in later epochs:

particular demands on the recording of proper names (personal names, place names)

of terms and designations in a foreign language

a widening of the sphere in which writing is used, that is, a widening of the circle of users as well as of specific contexts of usage (literature!)

the presence of several languages side by side as a phenomenon of limited “processes of globalization”

the elimination of ambiguities and orthographies prone to misunderstanding.

Be this as it may, in Mesopotamia the implementation of new “manners of writing” is evidently regulated by the alternate play of availability and need. This process led to a situation, masterfully described by Piotr Michalowski:

The early history of cuneiform might be characterized as one of an uneasy adaptation of an autonomous communication system to accommodate natural language. By the middle of the third millennium the new system was capable of representing full utterances, but it was still something of a mnemonic device to the extent that no attempt was made to represent with precision all aspects of language. Only kernel elements were noted, and these were not inscribed in the order in which they were read. Thus a verb, which in later writing might have numerous affixes, would only carry one or two prefixes. The reader was expected to provide the missing elements and to unscramble the signs into their proper sequence. The graphic elements needed for fairly accurate phonological representation of Sumerian language were all in place, […] but that was not the goal of the recording system. Michalowski 1994, 25

By the second quarter of the third millennium, this process seems to have reached a certain optimum: the proportion of

Despite the obvious capability to write texts entirely phonetically […] the resistance to a purely phonetic orthography which would have greatly simplified these writing systems suggests that certain ideological biases in favour of traditional logophonetic writing were working against Gelb’s ‘principle of economy aiming at the expression of linguistic forms by the smallest possible number of signs.’ Cooper 2004, 91

An interesting situation arises toward the end of the cuneiform cultures, more precisely, in Hellenistic times. For centuries past,

But there was at least one interesting attempt at a transfer of the cuneiform materials into a different writing system in order to maintain access to certain aspects of the cuneiform tradition. The so-called Graeco-Babylonica are a case in point.28 They are documents that transcribe texts from the

Writing is closely associated with the term text, referring to both the outer format as such, as well as to the inner structure, the fabric, the tissue of words and meanings. But textuality and the use of writing do not principally coincide as they pertain to different descriptive systems Ehlich 2007. De facto Egypt as well as Mesopotamia point to a multimedial textual concept, thus allowing for “texts” even in the earliest phases of writing Morenz 2007. Protocuneiform and archaic cuneiform documents represent in fact virtually open texts in

5.4 Literacy and the Material Aspects of Writing

Another perspective, too rarely adopted, has been recently highlighted by K. Lamberg-Karlowsky. Our attitude toward the role of writing is heavily biased by the particular nature of our evidence, the textual record itself being its main object of study and source of knowing. But it should be kept in mind that, although evidence seems to suggest a high degree of acceptance for cuneiform script (and its derivatives) many peoples did in fact renounce such a take-over. This especially holds true for the initial phase of literacy in the Ancient Near East:

With the exception of a single region […] every settlement ‘colonized’ by the literate i.e. during the so-called Uruk-expansion refused to adopt the written tablet as a communicative device. […] All indigenous communities exposed toliteracy, whether the Proto-Elamite culture on the Iranian Plateau, the Uruk in northern Mesopotamia and Anatolia, or the Egyptian in the Levant, refused to assimilate and adopt the written sign as a communication device. It is perhaps difficult for us to accept that writing, a technology which we highly prize, would be self-consciously avoided. Perhaps this is why shelves of books discuss the origin, function, and nature of writing, while the apparent avoidance of becoming literate is all but ignored. Lamberg-Karlovsky 2003, 63

Although it may seem to be a quite difficult undertaking to estimate the degree of literacy in Ancient Near Eastern societies, some general observations may be drawn from the available evidence-differing from time to time and from region to region. Thus it can be shown that one has to account not only for a generally restricted number of

Literacy then is not a constantly growing feature of Ancient Near Eastern civilizations and thus cannot be seen as a factor enabling or even fostering the process of the globalization of knowledge. On the contrary, the level of the use of writing varies on all scales, from the micro-level of individuals to the macro-level of entire societies. The oscillation between varying degrees of literacy is well known from other historical periods, but the closest parallels to the Ancient Near Eastern situations are offered by medieval Europe. From the eleventh century onwards, for example, a close connection between new approaches to doing business and literacy can be observed: the growth of literacy is a consequence of the production and retention of records, as well as an increasingly dense network of referential uses of written record Clanchy 1979.

But what about the consequences of a given implementation of script-based communication within a society, which to a large extent bases its system mainly on forms of oral communication? How does such a scriptural turn influence the authority of the spoken word?32

The transition fromlanguage as sound to writing as symbol is the same as the transition from voice to text and from chief to king. There is a relationship between authorship and authority. Writing is the isolating symbol of power. It isolates the literate and the powerful from those who are illiterate. In virtually every case in which writing is invented, it is not the author but the institutional context of authorship that yields the power. Initially, wherever one finds writing, the author is anonymous – a tool of administrative power directed by a central authority. Lamberg-Karlovsky 2003, 64–65

Being a tool as well as a sign of power and authority, writing must—especially in premodern societies—maintain itself in opposition to competing modes of representation, transmission, authority, and so forth. It has to continually prove its societal value. Some intriguing insights concerning the economic side of the implementation of writing in a society can be gained by means of a simple modification of the central theme of Coulmas’ book on

“Writing is an Asset”: Writing and Money in the Development of National Economics (chap. 2)

The Value of Writing: Factors of an Economic Profile of Writing (chap. 3)

Writing-related Expenditures of Government and Business (chap. 4)

Writing Careers: Economic Determinants of

Economy in Writing: Economic Aspects of the Writing System (chap. 6)

Writing Adaption: Differentiation and Integration (chap. 7)

It becomes immediately clear that the entanglement of economic interests and the role of writing are to be considered as important a factor as the globalization of knowledge, not only with regard to modern periods, but also to premodern times! Although these perspectives cannot be elaborated within this paper, I should like to point at least here to the institutional as well as to the institutionalized character of early writing, which not only has its bearing on obvious aspects such as the standardization of the system, but also on the content and extension of the knowledge encoded therein: the training of scribes becomes central to the formation and tradition of culturally relevant bodies of knowledge. However, at the same time, the fields of scribal engagement were thus shaped, controlled, and determined. Within their

The establishment of writing as a tool of documentation has had another direct impact on the overall organization of societies’ knowledge. The tablets written had to be stored and methods found for the systematic organization of the written record. Management of the written record was an essential activity within the sphere of

The use of writing enables the logical disciplining of thought Stetter 1990, 279. This at first glance somewhat banal observation is easily understandable with regard to the level of content. But of no less importance is the impact of the materiality of writing on the generation of new knowledge as well as on the reorganization and redirection of existing fields. It is the scriptural mediation of thought that is inevitably linked to the external format as well as to the internal organization of a writing system. Spatiality is a particular characteristic of writing (whereas language is not spatial, but at best linear!) thus extending the possibilities of the latter. The formal criteria, the aesthetic profile of a text, the metapragmatics of writing35 is a domain of knowledge in its own right, transferred within the practice of writing. Its effects can be observed not only in the development of previously unknown formats such as tables, which allow for a two-dimensional presentation of information. But also the subtle technical changes such as the shifting ergonomics of writing itself are to be taken into consideration. The morph (form), the external features of a writing system, to a certain extent directly condition its applicability, for example, with regards to the velocity of writing and reading. These relate, for example, to the possibility of multiplying texts, thus producing multiple sets of one and the same record, or making text easily available. Even the development of cursive writing styles follows from the ever increasing necessity of writing huge amounts of texts, which do not serve monumental or ceremonial purposes. Rationalization of the process of writing is often shaped by the demands of speech-related writing. On the other hand the graphic organization of written text relates to its perception. So, for instance, writing in scriptura continua is not only difficult for modern readers, but testifies to the tradition of reading as an oral activity Saenger 1994. The relation between language and writing may, according to the respective system, necessitate the conveyance of secondary information, for instance, modes, stress, intonation, even the indication of word boundaries, the end of phrases, and so forth. Thus many writing systems develop diagrammatical elements to render phenomena, which are not or cannot be represented on the sign-level (graphematic) itself, such as spatial distribution to mark word-boundaries, punctuation, to mark the end of phrases or the mode of speech (exclamation! request? citation “”), or segmentation of paragraphs to mark contextual boundaries Raible 1991a; these translate semantic macrostructures of texts, as well as microstructures of a spoken situation Frank 1993.

Besides

Within the long-lasting process of the globalization of knowledge writing as a dynamic, yet at the same time systematically controlled

as a media for the exchange, transfer, and storage of all sorts of knowledge

as a dimensional extension of cognitive facilities

as a shaper of thought, stimulating paths of reflection and articulation

as giving/limiting/excluding access to certain domains of knowledge

as affecting and transforming societies as a whole.

On different scales and within differing contexts they are concerned with the

References

Assmann, Jan (1992). Das kulturelle Gedächtnis: Schrift, Erinnerung und politische Identität in frühen Hochkulturen. Munich: Beck.

Astington, J.W., D.R. Olson (1990). Metacognitive and Metalinguistic Language. Applied Psychology 39: 77-87

Bandt, Cordula (2007). Der Traktat “Vom Mysterium der Buchstaben”: Kritischer Text mit Einführung, Übersetzung und Anmerkungen. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Blossfeld, Hans-Peter, Heather Hofmeister (2006). Globalization, Uncertainity and Women's Careers: An International Comparison. Northhampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Busi, Giulio (2001). The Grammatical Classification of Hebrew Letters as a Mystical Tool. In: Indigenous Grammar across Cultures Ed. by Hannes Kniffka. Frankfurt am Main: Lang 347-364

Cancik-Kirschbaum, Eva (2005). Beschreiben, Erklären, Deuten: Ein Beispiel für die Operationalisierung von Schrift im alten Zweistromland. In: Schrift: Kulturtechnik zwischen Auge, Hand und Maschine Ed. by Gernot Grube, Werner Kogge, W. K.. Reihe Kulturtechnik. Munich: Fink 399-411

- (2006). Der Anfang aller Schreibkunst ist der Keil. In: Die Geburt des Vokalalphabets aus dem Geist der Poesie: Schrift, Zahl und Ton im Medienverbund Ed. by Wolfgang Ernst, Friedrich Kittler. Reihe Kulturtechnik. Munich: Fink 121-149

- (2012). Phänomene von Schriftbildlichkeit in der keilschriftlichen Schreibkultur. In: Schriftbildlichkeit. Wahrnehmbarkeit, Materialität und Operativität von Notationen Ed. by S. Krämer, E. Cancik-Kirschbaum, E. CK.. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag 101-121

Cancik-Kirschbaum, Eva, Grégory Chambon (2006). Les caractères en formes de coins: le cas du cunéiform. Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale 100(1): 13-40

- (forthcoming). Les caractères en forme de coins 2: l'écriture cunéiforme comme phénomène historique en Mésopotamie et en Europe au XIXe siècle ap. J.-C.. Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale

Cancik-Kirschbaum, Eva, John Cale Johnson (forthcoming). The Megapragmatics of Writing: The Example of Cuneiform..

Cavigneaux, A. (1989). L'écriture et la réflexion linguistique en Mésopotamie. In: Histoire des idées linguistiques, tome 1: La naissance des métalangages en Orient et Occident Ed. by Sylvain Auroux. Philosophie et langage. Liège: Mardaga 99-118

Clanchy, Michael T. (1979). From Memory to Written Record: England 1066–1307. London: Arnold.

Cooper, Jerrold S. (2004). Babylonian Beginnings: The Origin of Cuneiform Writing System in Comparative Perspective. In: The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process Ed. by Stephen D. Houston. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 71-99

Coulmas, Florian (1992). Language and Economy. Oxford: Blackwell.

Damerow, Peter (1999). The Origins of Writing as a Problem of Historical Epistemology. Preprint 114. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science.

- (2007). The Material Culture of Calculation. In: Mathematisation and Demathematisation Ed. by Uwe Gellert, Eva Jablonka. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers 19-56

DeFrancis, John (1989). Visible Speech: The Diverse Oneness of Writing Systems. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

DeVries, Keith (2007). The Date of the Destruction Level at Gordion: Imports and the Local Sequence. In: Anatolien Iron Ages 6. The Proceedings of the Sixth Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium held at Eskiçehir, 16–20 August 2004 Ancient Near Eastern Studies. Leuven: Peeters 80-101

Diringer, David (1948). The Alphabet: A Key to the History of Mankind. New York: Philosophical Library.

Ehlich, Konrad (1980). Schriftentwicklung als gesellschaftliches Problemlösen. Zeitschrift für Semiotik 2(1,2): 335-359

- (2007). Textualität und Schriftlichkeit. In: Was ist ein Text?: Alttestamentliche, ägyptologische und altorientalistische Perspektiven Ed. by Ludwig D. Morenz, Stefan Schorch. Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft / Beihefte. Berlin: de Gruyter 3-17

Eisenberg, Peter (1989). Die Grammatikalisierung der Schrift: Zum Verhältnis von silbischer und morphematischer Struktur im Deutschen. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Germanistenverbandes 36: 20-29

Englund, Robert K. (1998). Texts from the Late Uruk Period. In: Mesopotamien: Späturuk-Zeit und Frühdynastische Zeit Ed. by Pascal Attinger, Markus Wäfler. Annäherungen. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 15-233

Finkel, Irving (2010). Strange Byways in Cuneiform Writing. In: The Idea of Writing. Play and Complexity Ed. by Alex Voogt, Finkel de. Leiden: Brill 9-25

Frank, Barbara (1993). Zur Entwicklung der graphischen Präsentation mittelalterlicher Texte. Osnabrücker Beiträge zur Sprachtheorie 47: 60-81

Frede, Dorothea, Brad Inwood (2005). Language and Learning: Philosophy of Language in the Hellenistic Age. Proceedings of the Ninth Symposium Hellenisticum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gaur, Albertine (1987). A History of Writing. London: British Library.

Gelb, Ignace J. (1963). A Study of Writing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Geller, M. J. (1997). The Last Wedge. Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 87(1): 43-95

Glassner, Jean-Jacques (2003). The Invention of the Cuneiform: Writing in Sumer. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Goldwasser, Orly (1995). From Icon to Metaphor: Studies in the Semiotics of the Hieroglyphs. Fribourg, Switzerland: University Press.

Goody, Jack (1986). The Logic of Writing and the Organization of Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goody, Jack, Ian Watt (1963). The Consequences of Literacy. Comparative Studies in Society and History 5(3): 304-345

Gramelsberger, Gabriele (2001) Semiotik und Simulation: Fortführung der Schrift ins Dynamische. Entwurf einer Symboltheorie der numerischen Simulation und ihrer Visualisierung. Doctoral Thesis. Berlin: Freie Universität.

Greenstein, E. L. (1984). The Phonology of the Akkadian Syllable Structure. Afroasiatic Linguistics 9(1): 1-71

Grube, Gernot, Werner Kogge, W. K. (2005). Schrift: Kulturtechnik zwischen Auge, Hand und Maschine. Munich: Fink.

Gumbrecht, Hans Ulrich, Karl Ludwig Pfeiffer (1988). Materialities of Communication. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Halverson, John (1992). Goody and the Implosion of the Literacy Thesis. Man 27(2): 301-317

Harris, Roy (1989). How Does Writing Restructure Thought?. Language and Communication 9(2–3): 99-106

Havelock, Eric Alfred (1976). Origins of Western Literacy: Four Lectures Delivered at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, Toronto, March 25–28, 1974. Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

- (1982). The Literate Revolution in Greece and Its Cultural Consequences. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Herriman, M.L. (1986). Metalinguistic Awareness and the Growth of Literacy. In: Literacy, Society and Schooling: A Reader Ed. by Suzanne DeCastell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Houston, Stephen D. (2004). The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hunger, Hermann (1968). Babylonische und assyrische Kolophone. Kevelaer: Butzon und Bercker.

Innis, Harold A. (1950). Empire and Communications. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Koch, Peter, Wulf Oesterreicher (1996). Schriftlichkeit und Sprache. In: Schrift und Schriftlichkeit (Writing and Its Use): Ein interdisziplinäres Handbuch Ed. by Hartmut Günther, Otto Ludwig. Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft. Berlin: De Gruyter 587-604

Krämer, Sybille (1997). Schrift und Episteme am Beispiel Descartes'. In: Schrift, Medien, Kognition: Über die Exteriorität des Geistes Ed. by Peter Koch, Sybille Krämer. Probleme der Semiotik. Tübingen: Stauffenburg-Verlag 105-126

Krämer, Sybille, Horst Bredekamp (2003). Bild, Schrift, Zahl. Munich: Fink-Verlag.

Krebernik, Manfred (2002). Von Zählsymbolen zur Keilschrift. In: Materialität und Medialität von Schrift Ed. by Erika Greber, Konrad Ehlich, K. E.. Schrift und Bild in Bewegung. Bielefeld: Aisthesis-Verlag 51-71

Lamberg-Karlovsky, C. C. (2003). To Write or Not to Write. In: Culture through Objects: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of P. R. S. Moorey Ed. by Timothy F. Potts, Michael Roaf, M. R.. Griffith Institute Publications. Oxford: Griffith Institute 59-75

Lévy-Bruhl, Lucien (1923). Primitive Mentality. London: George AllenUnwin.

Lloyd, Geoffrey (1983). Science, Folklore and Ideology: Studies in the Life Sciences in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Macdonald, M. C. A. (2005). Literacy in an Oral Environment. In: Writing and Ancient Near Eastern Society: Papers in Honour of Alan R. Millard Ed. by Piotr Bienkowski. Library of Hebrew Bible / Old Testament Studies. New York: TT Clark 49-118

Maul, St. M. (1999). Das Wort im Worte. Orthographie und Etymologie als hermeneutische Verfahren babylonischer Gelehrter. In: Commentaries - Kommentare Ed. by Glenn Most. Aporemata. Kritische Studien zur Philologiegeschichte. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 1-18

McLuhan, Marshall (1962). The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Mersch, Dieter (2000). Jenseits von Schrift: Die Performativität der Stimme. Dialektik: Zeitschrift für Kulturphilosophie

- (2002). Was sich zeigt: Materialität, Präsenz, Ereignis. Munich: Fink.

Michalowski, Piotr (1990). Early Mesopotamian Communicative Systems: Art, Literature, and Writing. In: Investigating Artistic Environments in the Ancient Near East: [Essays Presented at a Symposium Held in April 1988 at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery] Ed. by Ann Clyburn Gunter. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution 53-69

- (1994). Writing and Literacy in Early States: A Mesopotamianist Perspective. In: Literacy: Interdisciplinary Conversations Ed. by Deborah Keller-Cohen. Cresscill: Hampton Press 49-70

Morenz, Ludwig D. (2004). Bild-Buchstaben und symbolische Zeichen: Die Herausbildung der Schrift in der hohen Kultur Altägyptens. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- (2007). Wie die Schrift zu Text wurde: Ein komplexer medialer, mentalitäts- und sozialgeschichtlicher Prozeß. In: Was ist ein Text?: Alttestamentliche, ägyptologische und altorientalistische Perspektiven Ed. by Ludwig D. Morenz, Stefan Schorch. Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft / Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. Berlin: de Gruyter 18-46

Nissen, Hans Jörg, Peter Damerow, P. D. (1993). Archaic Bookkeeping: Early Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Olson, David R. (1996). Towards a Psychology of Literacy: On the Relations Between Speech and Writing. Cognition 60(1): 83-104

Ong, Walter J. (1982). Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London: Methuen.

Pedersén, Olof (1998). Archives and Libraries in the Ancient Near East, 1500–300 B.C. Bethseda, MD: CDL Press.

Petterson, John Sören (1996). Grammatological Studies: Writing and Its Relation to Speech. Uppsala: Uppsala University, Department of Linguistics.

Pongratz-Leisten, Beate (1999). Herrschaftswissen in Mesopotamien: Formen der Kommunikation zwischen Gott und König im 2. und 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Helsinki: Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project.

Postgate, Nicholas, Tao Wang, T. W. (1995). The Evidence for Early Writing: Utilitarian or Ceremonial?. Antiquity 69(264): 459-480

Raible, Wolfgang (1991a). Die Semiotik der Textgestalt: Erscheinungsformen und Folgen eines kulturellen Evolutionsprozesses. Heidelberg: Winter.

- (1991b). Zur Entwicklung von Alphabetschrift-Systemen: is fecit cui prodest; vorgetragen am 21. April 1990. Heidelberg: Winter.

- (1999). Kognitive Aspekte des Schreibens: Vorgetragen am 23. November 1996. Heidelberg: Winter.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques (1966). Essay on the Origin of Languages. In: On the Origin of Language: Two Essays Ed. by John H. Moran, Alexander Gode. Milestones of Thought. New York: Ungar 1-74

Rubio (2006). Writing in Another Tongue: Alloglottography in the Ancient Near East. In: Margins of Writing, Origins of Cultures Ed. by S. Sanders. Oriental Institute Seminars. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 33-66

Saenger, Paul (1994). Word Separation and Its Implication for Manuscript Production. In: Rationalisierung der Buchherstellung im Mittelalter und in der frühen Neuzeit: Ergebnisse eines Buchgeschichtlichen Seminars, Wolfenbüttel, 12.–14. November 1990 Ed. by Peter Rück. Elementa diplomatica. Marburg an der Lahnn: Institut für Historische Hilfswissenschaften 41-50

Sass, Benjamin (2005). The Alphabet at the Turn of the Millennium. The West Semitic Akphabet ca. 1150–850 BCE; the Antiquity of Arabian, Greek, and Phrygian Alphabets. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology.

Selz, Gebhard J. (2000). Schrifterfindung als Ausformung eines reflexiven Zeichensystems. Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes 90: 169-200

- (2007). Offene und geschlossene Texte im frühen Mesopotamien: Zu einer Text-Hermeneutik zwischen Individualisierung und Universalisierung. In: Was ist ein Text?: alttestamentliche, ägyptologische und altorientalistische Perspektiven Ed. by Ludwig Morenz, Stefan Schorch. Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft / Beihefte. Berlin: de Gruyter 64-89

Sherrat, Susan (2003). Visible Writing: Questions of Script and Identity in Early Iron Age Greece and Cyprus. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 22(3): 225-242

Silverstein, Michael (1993). Metapragmatic Discourse and Metapragmatic Function. In: Reflexive Language: Reported Speech and Metapragmatics Ed. by John A. Lucy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 33-58

Silverstein, Michael, Greg Urban (1996). The Natural History of Discourse. In: Natural Histories of Discourse Ed. by Michael Silverstein, Greg Urban. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1-17

Soldt, Wilfred H. (2010). The Adaptation of the Cuneiform Script to Foreign Languages. In: The Idea of Writing. Play and Complexity Ed. by Alex Voogt, Finkel de. Leiden: Brill 117-127

Stetter, Christian (1990). Grammatik und Schrift: Überlegungen zu einer Phänomenologie der Syntax. In: Sprachtheorie und Theorie der Sprachwissenschaft: Geschichte und Perspektiven; Festschrift für Rudolf Engler zum 60. Geburtstag Ed. by Ricarda Liver. Tübinger Beiträge zur Linguistik. Tübingen: Narr 272-283

- (1997). Schrift und Sprache. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Streck, M. (2001). Keilschrift und Alphabet. In: Hieroglyphen, Alphabete, Schriftreformen: Studien zu Multiliteralismus, Schriftwechsel und Orthographieneuregelungen Ed. by D. Borchers, F. Kammerzell, F. K.. Ligua Aegyptia Studia monographica. Göttingen: Seminar für Ägyptologie und Koptologie 77-97

Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja (1990). Magic, Science, Religion, and the Scope of Rationality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Trabant, Jürgen (2006). Europäisches Sprachdenken: Von Platon bis Wittgenstein. Munich: Beck.

Veenhof, Klaas Roelof (1986). Cuneiform Archives and Libraries: Papers Read at the 30e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Leiden, 4–8 July 1983. Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul.

Villers, Jürgen (2005). Das Paradigma des Alphabets: Platon und die Schriftbedingtheit der Philosophie. Würzburg: Königshausen und Neumann.

Westenholz, Aage (2007). The Greco-Babyloniaca Once Again. Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie 97(2): 262-313

Whittaker, Gordon (2001). The Dawn of Writing and Phoneticism. In: Hieroglyphen, Alphabete, Schriftformen: Studien zu Multiliteralismus, Schriftwechsel und Orthographieneuregelungen Ed. by Dörte Borchers, Frank Kammerzell, F. K.. Lingua aegyptica / Studia monographica. Göttingen: Seminar für Ägyptologie und Koptologie 11-50

Wilcke, Claus (2000). Wer las und schrieb in Babylonien und Assyrien: Überlegungen zur Literalität im Alten Zweistromland. Munich: Beck.

Footnotes

This chapter has benefited from the critical comments of P. Damerow, M. Hyman, J.C. Johnson, M. Krebernik and G. Selz.

The notions of the term Kulturtechnik adopted here are based on a concept, which guides the research of the Hermann von Helmholtz-Zentrum für Kulturtechnik at Humboldt-University, Berlin, especially the DFG-funded research-group “Bild – Schrift – Zahl” (2001–2007). See Krämer and Bredekamp 2003, esp. the introduction; furthermore Grube et.al. 2005.

A sound overview of the repeated incidences of invention can be found in Houston 2004, for general information, see Raible 1991b. For an interesting new empirical wrinkle vis-à-vis the early transmission toward the Eastern Aegean, see DeVries 2007, 96–98; the date of transmission is discussed controversially in Sass 2005.

The term “globalization” does not lend itself easily to premodern societies and early civilizations. However, the notion of “global” is relative, to be looked at under the particular emic perspective of a given society. Thus the kings of Sumer and Akkad assumed the titles “king of wholeness, king of the four quarters of the world,” emphasizing their sovereignty as “global.” Moreover, if related to this “scaled globality” the conditions in the Ancient Near East meet in a correspondingly scaled modification the definition in Blossfeld and Hofmeister 2006, 8: “We define globalization by four interrelated structural shifts: (1) the internationalization of markets in terms of labor, capital and goods and decline of national borders (2) intensified competition through deregulation, privatization and liberalization (3) accelerated spread of networks and knowledge via new communication and information (4) the rising importance of world markets and their increasing dependency on random shocks.”

For a critical view, cf. Whittaker 2001.

With regards to the overall success of the technique, this aspect of writing is certainly of utmost relevance. Indeed, linguistic knowledge as most relevant for the creation of a writing system as such is perhaps the earliest form of systematically, but indirectly encoded, knowledge. This holds especially true with regard to early forms of linguistic thought, which become visible in the organizational mode of writing systems Cavigneaux 1989. A typical feature is, for example, the systematics of sign encoding: primary objects (such as animals, goods, and so forth), actions (encoded in verbs such as “to deliver”) and actors (names, titles, functions) vs. less relevant parameters such as modality or aspect. For a (debated) systematic approach as regards Egyptian hieroglyphs, see Goldwasser 1995.

Examples given typically relate to the East Asian and European traditions, but similar concepts can be found in other cultural contexts.

See Diringer 1948; Gelb 1963, 201; Havelock 1982, 11. The effects and outcomes of other successful solutions in the history of writing were generally left aside, or judged to be incomplete forerunners or precursors. With regard to the history of Ancient Near Eastern writing systems, see Michalowski 1990, 57–59; Cancik-Kirschbaum 2005; Cancik-Kirschbaum 2006; Cancik-Kirschbaum and Chambon 2006; see also (Cancik-Kirschbaum and Chambon forthcoming forthcoming).

With varying shifts of emphasis, among others, McLuhan 1962; Goody and Watt 1963; Havelock 1976; Havelock 1982; Ong 1982; Goody 1986; Halverson 1992.

Such as Lévy-Bruhl 1923; Lloyd 1983; Tambiah 1990.

See Innis 1950; McLuhan 1962; Havelock 1982.

A sound overview is given in Olson 1996, chap. 3.

See, for example, Gaur 1987; Harris 1989.

See Olson 1996, 89; see furthermore Herriman 1986; Astington and Olson 1990.

See Maul 1999; further on the role of sign-shapes and understanding, see Finkel 2010.

Difficulties arise with the metaphorical use of “writing” as, for example, with “genome sequences (and the relevant terminology (transcriptase …)” and other fields).

The acknowledgment of both the linguistic-discursive and the iconic-operative aspects of writing has considerable consequences as regards the analysis of the genesis of writing systems Cancik-Kirschbaum 2012.

It goes without saying that this special field is itself part of and was shaped according to the outlines of its supporting cultural background, by its perception of the world and its governing principles, see Selz 2000, 171.

The so-called alphabetic technique co-existed with the traditional systems of writing and finally replaced them.

Translation, see Rubio 2006, 38–39.

Cf. for example, Soldt 2010.

So, for instance, morphematic (that is, focusing on the semantic identity of a word) writing conventions in alphabetical or syllabic systems will heavily influence phonetic adequacy. The recent orthographic reform of German, for example, made use of that principle. For instance, the word for the stem of a plant used to be spelled STENGEL, but this has been changed to STÄNGEL to clearly designate its etymological derivation form “STANGE” (tiny pole). But the phonetic reality is that we all articulate the |e| rather than the |ä|. On the other hand, syllabic or phonographic renderings of originally morphophonemically structured writings (typically, logogramms, one word = one sign) may considerably hinder the process of perceptive understanding.

See Geller 1997; Westenholz 2007.

See Wilcke 2000; Macdonald 2005.

See Assmann 1992; Raible 1999.

For a systematic approach, see Wilcke 2000.

The role of “materiality” with regard to early textual culture as Ancient Near Eastern societies still remains to be investigated. But the range of possible implications is illustrated, for instance, in Gumbrecht and Pfeiffer 1988.

A representative collection and overview is given in Hunger 1968.

See Veenhof 1986; Pedersén 1998.

The term is prominent in anthropological linguistics, but not in grammatology, see Silverstein 1993.