Chapter structure

- 4.1 Introduction

- 4.2 Terminology and Ideology

- 4.3 Inverting Kroeber’s Stimulus Diffusion Model: From Polemics to Applied Science

- 4.4 A Eurasian Problem: Western Influences in the Development of Chinese Metallurgy

- 4.5 New Perspectives on an Old Problem

- 4.6 Perspectives on the Study of Technology Transfer in Eurasian Metallurgy

- 4.7 Fellow Travelers in Eurasian Transfers

- 4.8 Conclusions

- References

- Footnotes

4.1 Introduction

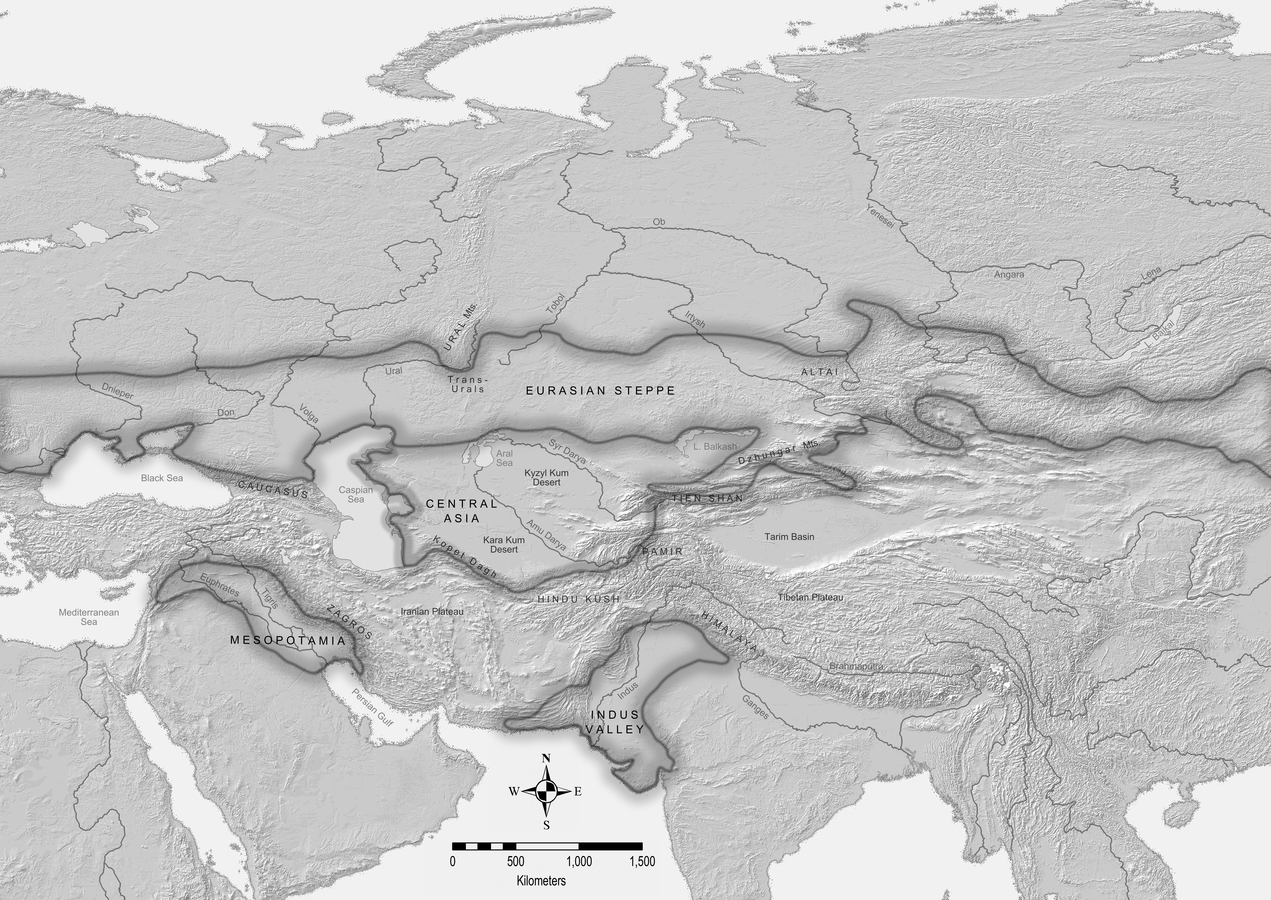

The pre-modern transfer of knowledge within Eurasia had to contend with a complex set of both physical and mental obstacles. Deserts, mountains and oceans had to be crossed, but so too did

Fig. 4.1: Map of Eurasia showing the regions of greatest relevance to this chapter Frachetti and Rouse 2012, Fig. 36.1. With kind permission of the authors.

The enormity of the Eurasian landmass, not to mention the multiplicity of linguistic and cultural entities inhabiting it, have rarely, if ever, been viewed by archaeologists as insurmountable impediments to long-range contacts between the many cultures inhabiting it in antiquity. Journals such as Eurasia Septentrionalis Antiqua: Journal for East European and North-Asiatic Archaeology and Ethnography (1927–1938), published by the Finnish Society of Archaeology, or the more recent Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia: An international journal of comparative studies in history and archaeology (established 1995) bear witness to the fact that archaeologists have been thinking on an inter-continental scale for many, many years. Nor have such studies been limited to discussions of shared art styles or artifact types. The possibility that

4.2 Terminology and Ideology

Several years after Childe delivered his lecture, the American anthropologist Alfred Louis Kroeber published a very different paper on what he termed

The consequence is that we have here what from one angle is nothing else than an invention. Superficially it is a “parallel,” in the technical language of ethnology. However, it is equally significant that the invention, although original so far as Europeans were concerned, was not really independent. Kroeber 1940, 2

In this context Kroeber’s views anticipated those of the eminent MIT metallurgist Cyril Stanley Smith who, almost forty years later, stressed the importance of studying “why a society will not absorb things into which it is brought into contact,” observing:

A human culture, existing at the apex of a long chain of historical selectivity cannot easily incorporate large chunks of another, though occasionally small things can seep in without opposition and later interact to form a nucleus that can grow by rearranging the connections between things already present. Smith 1977, 84–85

Viewpoints like Kroeber’s (and later Smith’s) became increasingly unpopular during the 1960s and 1970s as

It was not just theoretical underpinnings that were to blame for the increasingly geographically narrow views of archaeologists. Combined with an attitudinal prejudice against anything that smacked of

[…] no one wanted to draw far-reaching conclusions or to develop wide-ranging theories. This is in keeping with the spirit of the times: we are in an age of cautious and detailed specialization, an age suspicious of hypothetical speculation and the “great theory.” […] Theories based upon influences from outside a given archaeological culture, theories using traditional ideas aboutmigration and diffusion, are now anathema to most prehistorians and field archaeologists. […] In this sense it could be said that everyone systematically ignored the theme of the symposium, and indeed such charges were made during the course of the meeting. In defense, I believe that most scholars would agree that we are simply not in a position to discuss the influence of East upon West or vice versa […] We are still too busy trying to figure out what was going on in a particular area to worry about the possibility of cross-cultural contacts. Muhly 1981, 126–127

Many archaeologists and ancient historians working today would probably agree with Muhly as they continue, thirty years on, “trying to figure out what was going on.” Yet it could be argued that focusing on the concrete outcomes of technological praxis—for example, harvested cultivars, decorated weaponry, or painted pottery, whether at the macroscopic or the microscopic level—is neither the only nor the best way of investigating intercultural contact and

4.3 Inverting Kroeber’s Stimulus Diffusion Model: From Polemics to Applied Science

In his discussion of

Style is the manifest expression, on the behavioral level, of cultural patterning that is usually neither cognitively known nor even knowable by members of a cultural community except by scientists who may have analysed successfully their own cultural patterns or those of other cultures. Lechtman 1977, 4

Although these concepts are applicable to any sort of

4.4 A Eurasian Problem: Western Influences in the Development of Chinese Metallurgy

Nineteenth-century scholars, including the Assyriologist W. St. Chad Boscawen (1854–1913),

Briefly stated, there exist wildly divergent views on the extent to which Chinese

such as thebronze ceremonial vessels […] like nothing in the West […] There are, however, other bronze artifacts from Anyang which are of convincingly Western type, namely helmets (cf. Early Dynastic forms in Mesopotamia), socketed celts of European Late Bronze Age type, and socketed spearheads with two loops for binding, like those occurring in Europe in the Middle Bronze Age. Ward 1954, 138

Two years later Max Loehr argued very strongly for external, Western influence on the earliest development of

Contrast these positions with that of Ho Ping-Ti two decades later. In an unabashed apologia for the independence of Chinese civilization, Ho rejected any suggestion of foreign influence from the West; argued for the autochthonous origins of “the primitive copper

It is clearly true thatmetallurgy did not creep slowly and continuously into China from its boundaries, but, taking a world view, can we be sure that the nuclear suggestion did not come from somewhere else by a route that left no record of its passage? Bernard gives a world map on page 16, which combines his own data with those of Colin Renfrew, who has argued strongly for similar independence of the earliest metallurgical developments in the Balkans. The map shows no fewer than six “independent regions of early metallurgy,” with China the last of all to appear. This reviewer, while granting that technical elaboration occurs differently in different locations, finds it impossible to believe that the basic ideas of metallurgy were so easy to come by ad nuovo. It is incredibly difficult to invent anything really new, while information, albeit garbled and incomplete, is easily carried by travelers. Does transmission have to leave a record? […] On a very detailed scale, there would be little evidence beyond intangible style for links between the sites noted in China itself. One must take into account the stage of development involved in a transfer, the stage both of the technological details and of the receiving culture. Rather than postulating independent invention, it seems to me that the interesting questions concern how, with many nuclei in the air, a strong culture can incorporate into its own fabric as compatible only very few of the things it hears of, while resisting most suggestions that come to it from continuing if superficial contacts with neighboring and sometimes remote peoples. Regardless of whether the first idea of making and shaping metals arose spontaneously in China or came from outside by a barrier passing process akin to quantum-mechanical tunneling, there can be no question that the subsequent development of metallurgy was indigenous. The furnaces, the crucibles, the molds, and the almost exclusive dependence on casting, even of iron when it appears, all bear the unique stamp of that great civilization.3

In 1993 Donald Wagner leapt to the defense of Ho, Bernard and Sato, launching a determined attack against

The anti-diffusionists cannot hope to provide the sort of positive proof that the diffusionists may, under fortunate circumstances, be able to provide. It is therefore incumbent on the diffusionists to provide positive empirical evidence. Broad untestable opinions […] are not useful in a scientific discussion. Wagner 1993, 33

The polemical positions adopted in this debate are obvious. Full of post-colonial outrage, one camp is morally affronted by the very notion that a civilization the size of China should owe anything to outside influence, while some hard-nosed metallurgists and historians of science cannot let go of the sneaking suspicion that somewhere along the line, the esoteric, technical lore of

4.5 New Perspectives on an Old Problem

Mei’s research has isolated two important sets of external linkages in the earliest copper and

The second and, in my view, far more important source of linkages is with the

Mei has conclusively demonstrated the infiltration of

Where might such complex technology have originated? The predominance of true

The original stimulus formetallurgy and metalworking in the Andronovo community came from the west, from the region where the productive centers of the CMP (Circum-Pontic Metallurgical Province), which was in collapse, or the workshops of the CMP-EAMP (Eurasian Metallurgical Province). Chernykh 1992, 214

Other metals besides

gave them access to Inner Asia via the ancient ‘Fur Route,’ a complex trading network that crossed Eurasia long before the opening of the more southerly ‘Silk Route.’ The Fur Route ran in an eastward direction north of the fiftieth parallel from the Caspian Sea to southern Siberia, and then southward to ancient China and its border areas via the Amur Valley. The existence of this route explains the presence in Hebei of an Andronovan type of funnel-shaped earring. Bunker 1993, 31

As Joseph Needham wrote in 1964:

I believe that the longer the time which has elapsed between the first successful achievement of an art or invention in one place and its appearance in another, the more difficult it is to entertain the idea of a purely independent invention. Needham 1964, 403

Although he was referring to the much later, westward diffusion to Europe, via Iran, of Chinese

In the future, additional technical studies that throw light on the precise techniques used by the earliest metallurgists in

In conclusion, despite the rejection of the perspectives of

If any culture in the West did convey elements likely to promote metalworking in North-China, it must have been theAndronovo culture. Loehr 1956, 86

4.6 Perspectives on the Study of Technology Transfer in Eurasian Metallurgy

At the

First, achieving anything like a “Eurasian” perspective is incredibly difficult, given the multiplicity of sources, in a multitude of languages, that must be assessed. Archaeologists who have dealt with Central Asian material are acutely aware of the enormous difference in the potential for creative scholarship between the Soviet and the post-Soviet eras. Access to Soviet archaeological literature was extremely difficult for Western scholars prior to the 1980s, when active cooperation with Soviet scholars began a trend which has obviously

At the same time, Chernykh’s horizon ended at the borders of Mongolia and

One can, therefore, only marvel all the more at a scholar like Max Loehr whose prescience in divining the likelihood of an

4.7 Fellow Travelers in Eurasian Transfers

Tin – the sine qua non of

Bactrian camel – it is now clear that the Bactrian camel, which originated in Mongolia (Baotou) and

Fig. 4.2: Herd of Camelus bactrianus in the Nubra Valley, Ladakh, India.Photo: John E. Hill, with kind permission.

Wheat –

Horse – As Jansen et.al. 2002, 10910 stress:

Although there are claims forhorse domestication as early as 4500 BCE for Iberia and the Eurasian steppe, the earliest undisputed evidence are chariot burials dating to c. 2000 BCE from Krivoe Ozero (Sintashta-Petrovka culture) on the Ural steppe.9

Piggott now places the first development of […] chariots within the Timber Grave/Andronovo cultures of south Russia, between the Ural mountains and the Irtysh river and dating to ca. 1700–1400 BCE (calculated from uncalibrated dates which, on the basis of the MASCA 1973 calibration, would be 2060–1600 BCE).Innovations there spread both to the west (as far as Mycenaean Greece) and to the east, where chariot burials from Shang Dynasty China have almost their exact counterparts in those from the waterlogged tombs at Lchashen on Lake Sevan in the Armenian SSR. Muhly 1988, 89

Speaking of these latter finds, which were compared in great detail with Shang-period chariots in China, E. L. Shaughnessy wrote:

If we now compare the technical characteristics of the Chinese and Trans-Caucasian chariots, I think there can be no doubt as to their typological similarity, or even identity. Shaughnessy 1988, 206

Bunker has suggested that the

4.8 Conclusions

The work of Chernykh, Mei and Li, and its evaluation by metallurgists like Pigott, suggest to me very strongly that the pendulum has swung well away from the adamant rejection of

At the present time the available studies of mtDNA from Eurasian populations10 do not include material contemporary with the period of postulated

Of course, on their own such studies do not merely answer old questions, they pose new ones. Did the posited

References

Bennett, Casey C., Frederika A. Kaestle (2006). Reanalysis of Eurasian Population History: Ancient DNA Evidence of Population Affinities. Human Biology 78(4): 413-440

Binford, Lewis R. (1965). Archaeological Systematics and the Study of Culture Process. American Antiquity 31(2): 203-210

Boroffka, N., J. Cierny, J. C., Lutz J., L. J., J. Lutz (2002). Bronze Age Tin from Central Asia: Preliminary Notes. In: Ancient Interactions: East and West in Eurasia Ed. by Katie Boyle, Colin Renfrew, C. R.. Cambridge: McDonald Institute 135-159

Boscawen, W. St. C. (1888). Shen-Nung and Sargon. The Babylonian and Oriental Record 2: 208-209

Bunker, Emma C. (1993). Gold in the Ancient Chinese World: A Cultural Puzzle. Artibus Asiae 53(1/2): 27-50

Cahill, James (1989). Max Loehr (1903–1988). The Journal of Asian Studies 48(1): 240

Caldwell, Joseph R. (1964). Interaction Spheres in Prehistory. In: Hopewellian Studies Ed. by Joseph R. Caldwell, Robert L. Hall. Springfield, Ill.: Illinois State Museum Scientific Papers 134-143

Chang, K. C. (1978). The Origin of Chinese Civilization: A Review. Journal of the American Oriental Society 98(1): 85-91

Chen, K.-T., Frederik T. Hiebert (1995). The Late Prehistory of Xinjiang in Relation to Its Neighbors. Journal of World Prehistory 9(2): 243-300

Chernykh, E. N. (1992). Ancient Metallurgy in the USSR: The Early Metal Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Childe, V. G. (1937). A Prehistorian's Interpretation of Diffusion. In: Independence, Convergence, and Borrowing in Institutions, Thought, and Art Harvard Tercentenary Publications. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 3-21

Clark, Graheme (1969). World Prehistory: An Outline. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Comas, D., F. Calafell, F. C., Mateu F., M. F., E. Mateu, E. M., Pérez-Lezaun E., PL. E., A. Pérez-Lezaun, A. PL., Bosch A. (1998). Trading Genes along the Silk Road: mtDNA Sequences and the Origin of Central Asian Populations. American Journal of Human Genetics 63(6): 1824-1838

Edkins, Joseph (1871). China's Place in Philology: An Attempt to Show that the Languages of Europe and Asia Have a Common Origin. London: Trübner.

Frachetti, Michael D., Lynne M. Rouse (2012). Central Asia, the Steppe, and the Near East, 2500–1500 BC. In: A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East Ed. by Daniel T. Potts. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell 687-705

Härke, Heinrich (1998). Archaeologists and Migrations: A Problem of Attitude?. Current Anthropology 39(1): 19-45

Hemphill, Brian E., J. P. Mallory (2004). Horse-mounted Invaders from the Russo-Kazakh Steppe or Agricultural Colonists from Western Central Asia? A Craniometric Investigation of the Bronze Age Settlement of Xinjiang. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 124(3): 199-222

Ho, P.-T. (1975). The Cradle of the East: An Inquiry into the Indigenous Origins of Techniques and Ideas of Neolithic and Early Historic China, 5000–1000 B.C. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jansen, Thomas, Peter Forster, P. F., Levine Peter, L. P., Marsha A. Levine, M.A. L., Oelke Marsha A. (2002). Mitochondrial DNA and the Origins of the Domestic Horse. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99(16): 10905-10910

Kaplan, Sidney M. (1957). Review of Loehr, M., Chinese Bronze Age Weapons. American Anthropologist 59(2): 377-379

Kroeber, A. L. (1940). Stimulus Diffusion. American Anthropologist 42(1): 1-20

Lechtman, Heather (1977). Style in Technology - Some Early Thoughts. In: Material Culture, Styles, Organization, and Dynamics of Technology Ed. by Heather Lechtman, Robert S. Merrill. St. Paul, Minn.: West 3-20

Levine, Marsha A. (1999). Botai and the Origins of Horse Domestication. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 18(1): 29-78

Li, S. (2002). The Interaction Between Northwest China and Central Asia During the Second Millenium B.C.: An Archaeological Perspective. In: Ancient Interactions: East and West in Eurasia Ed. by Katie Boyle, Colin Renfrew, C. R.. Cambridge: McDonald Institute 171-182

Lightfoot, K.G., A. Martinez (1995). Frontiers and Boundaries in Archaelolgical Perspective. Annual Review of Anthropology

Linduff, K. M. (2005). How Far East Does the Eurasian Metallurgical Tradition Extend?. Rossijskaya Archaelogia

Loehr, Max (1956). Chinese Bronze Age Weapons: the Werner Jannings Collection in the Chinese National Palace Museum, Peking. Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan Press.

Mei, J., C. Shell, C. S., Li C. (1998). A Metallurgical Study of Early Copper and Bronze Artefacts from Xinjiang, China. Bulletin of the Metals Museum 30: 1-22

Mei, Jianjun (2000). Copper and Bronze Metallurgy in Late Prehistoric Xinjiang: Its Cultural Context and Relationship with Neighbouring Regions. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Mei, Jianjun, Colin Shell (1999). The Existence of Andronovo Cultural Influence in Xinjiang During the 2nd Millenium B.C. Antiquity 73(281): 570

Montelius, Oscar (1899). Der Orient und Europa: Einfluss der orientalischen Cultur auf Europa bis zur Mitte des letzten Jahrtausends v. Chr. Stockholm: Königliche Akademie der schönen Wissenschaften, Geschichte und Alterthumskunde.

Muhly, James D. (1981). The Origin of Agriculture and Technology - West or East Asia. Technology and Culture 22(1): 125-148

- (1988). Review of Stuart Piggot, The Earliest Wheeled Transport: From the Atlantic Coast to the Caspian Sea. Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research

Needham, Joseph (1964). Chinese Priorities in Cast Iron Metallurgy. Technology and Culture 5(3): 398-404

Parker, E. H. (1883). Chinese and Sanskrit. China Review 12(6): 498-507

Pigott, Vincent C. (2002). Review of Jianjun Mei, Copper and Bronze Metallurgy in Late Prehistoric Xinjiang. Asian Perspectives 41(1): 167-170

Potts, Daniel T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- (2004). Camel Hybridization and the Role of . Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 47(2): 143-165

Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1988). Historical Perspectives on the Introduction of the Chariot into China. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 48(1): 189-237

Sherratt, Andrew (2006). The Trans-Eurasian Exchange: The Prehistory of Chinese Relations with the West. In: Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World Ed. by Victor H. Mair. Perspectives on the Global Past. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press 30-61

Smith, Cyril Stanley (1977). Review of Bernard, N. and Sato, T., Metallurgical Remains of Ancient China; and Ho, P.-T., The Cradle of the East: An Enquiry into the Indigenous Origins of Techniques and Ideas of Neolithic and Early Historic China, 5000–1000 B.C. Technology and Culture 18(1): 80-86

Terrien de Lacouperie, Albert Etienne (1885). Babylonian and Old Chinese Measures. The Academy: A Weekly Review of Literature, Science and Art 28(701): 243-244

- (1894). Western Origin of the Early Chinese Civilisation from 2,300 B. C. to 200 A. D.: Or Chapters on the Elements Derived from the Old Civilisations of West Asia in the Information of the Ancient Chinese Culture. London: Asher.

Thornton, Christopher P., Theodore G. Schurr (2004). Genes, Language and Culture: An Example from the Tarim Basin. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 23(1): 83-106

Trigger, Bruce G. (1989). A History of Archaeological Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wagner, Donald B. (1993). Iron and Steel in Ancient China. Leiden: Brill.

- (1999). The Earliest Use of Iron in China. In: Metals in Antiquity Ed. by Suzanne M. M. Young, A. Mark Pollard, A.M. P., Budd A. Mark. BAR International Series. Oxford: Archaeopress 1-9

Ward, Lauriston (1954). The Relative Chronology of China through the Han Period. In: Relative Chronologies in Old World Archaeology Ed. by Robert W. Ehrich. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 130-144

Wertime, Theodore A. (1964). Asian Influences on European Metallurgy. Technology and Culture 5(3): 391-397

White, Lynn Jr. (1960). Tibet, India and Malaya as Sources of Western Medieval Technology. American Historical Review 65(3): 515-526

Footnotes

For a useful review of the main proponents of diffusionism, see Trigger 1989, 150–160, particularly Oscar Montelius’ ex oriente lux views of European cultural development and its Near Eastern antecedents; cf. Montelius 1899.

See, for example, Edkins 1871; Parker 1883; Terrien de Lacouperie 1885; Boscawen 1888; Terrien de Lacouperie 1894.

Smith 1977, 81–82, cf. Chang 1978.

Cf. Pigott 2002.

Cf. White 1960; Wertime 1964; on Chinese iron, see esp. Wagner 1999.

Cf. Sherratt 2006.

Cf. Linduff 2005 who suggests that even this may be a Eurasian rather than a Chinese invention.

Cf. Levine 1999.

For example, Comas et.al. 1998,Bennett and Kaestle 2006.

Cf. Thornton and Schurr 2004, 93–94, citing mtDNA research by Cui Yinqui at Jilin Univ. suggesting “the earliest mummies of the southern Tarim Basin grouped closely with the modern Sardinian and Basque samples without evidence for any mtDNA contribution from the east.”

They were conducted by Chinese anthropologist K. Han and published in China in the 1980s and early 1990s. For references, see Li 2002, 181.