14.1 Introduction

One of the least appreciated yet most amazing categories within the photographic discourse are “duplicates” or doubles. Duplicates are not identical, as is often thought, but they are almost identical copies. This understanding of the term is more prevalent today, as we have been becoming more captivated by a material point of view categorizing each photographic copy as an original autonomous object, a unique record of its own history, instead of as a plain bearer of photogenic information. Joan M. Schwartz defines duplicates aptly as “multiple original photographic documents, based on the same image, but made at various times, for diverse purposes and different audiences” (Schwartz 1995, 46). Nonetheless, while bearing in mind the complexity and relativity of the term “duplicate,” I believe that it serves our present purposes quite well.1

The potential of duplicates can be very well explored in eight photographs by Andreas Groll (1812–1872) from the collection of the Institute of Art History (IAH) of the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague. This paper aims to demonstrate that duplicates can be a valuable and irreplaceable source of knowledge, able to rewrite an established narrative order. I argue that they can serve as a perfect means to learn about production, distribution, as well as past and present reception and application of photographs in both specific and general contexts. Also, I argue that one should always ask “whether” to discard the doubles, rather than “how” or “when” as can sometimes be heard even from promoters of the “photo-object” approach that stresses the importance of material uniqueness of each photograph (Caraffa 2011, 23).

In the first part, I will introduce the origins and the image content of the pictures in question. Then I will look at some of the material aspects and specific qualities of the eight photographs as individual objects. In the third and the fourth sections, I elucidate two periods of time when our “doubles” came together for the first time ever and actually turned into a series, and as such became a subject of research. I will conclude with reflections about the need and the consequences of our knowledge of duplicate photographs with regard to a specific case on the one hand, and to the common history of photography on the other.

14.2 The image: the town hall in Prague’s Old Town

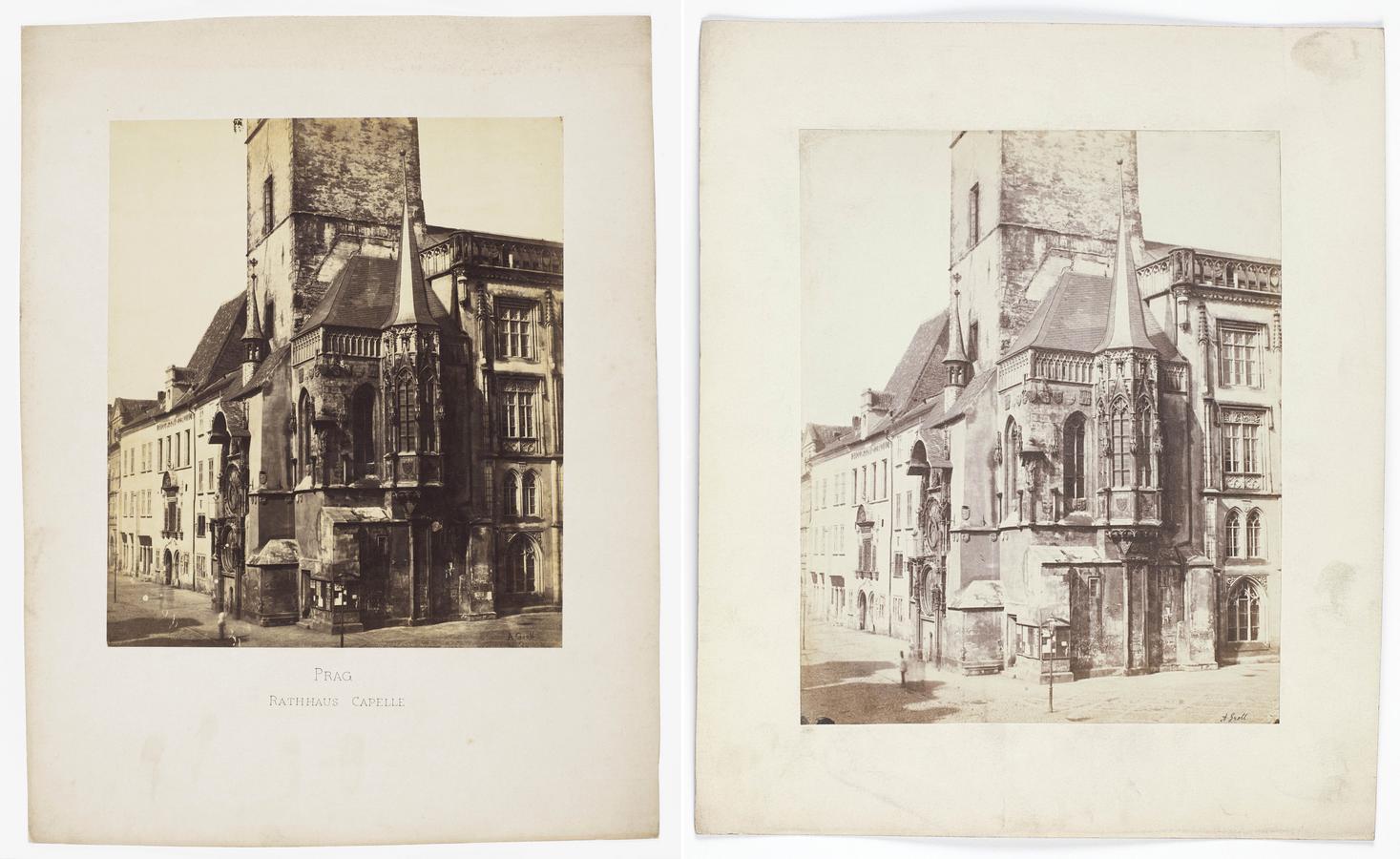

Fig. 1: The series of eight photographs of the town hall in Prague’s Old Town by Andreas Groll, 1856, Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. nos. 572–579, photo: Petra Trnková.

The eight photographs in question (see Fig. 1), which were created by Groll in the 1850s–1860s, depict one of the best known and most recorded edifices in Prague—the town hall in the Old Town with its famous astronomical clock. If we look at guide books and prints of the period, we will see that the popularity of this eminent building and its picturesque surroundings among tourists dates back at least to the early nineteenth century. Tourists were not the only ones enchanted, however. Since the building served as authentic evidence of the famous past of the Bohemian capital, it also attracted attention from ciceroni as well as scientists—archaeologists and historians of architecture—throughout the whole nineteenth century.

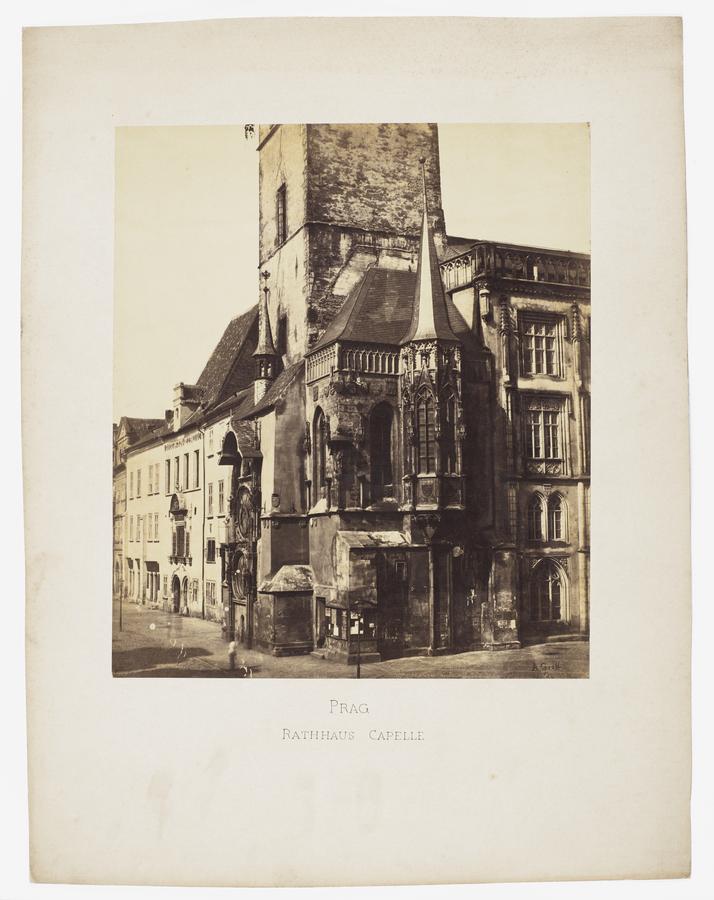

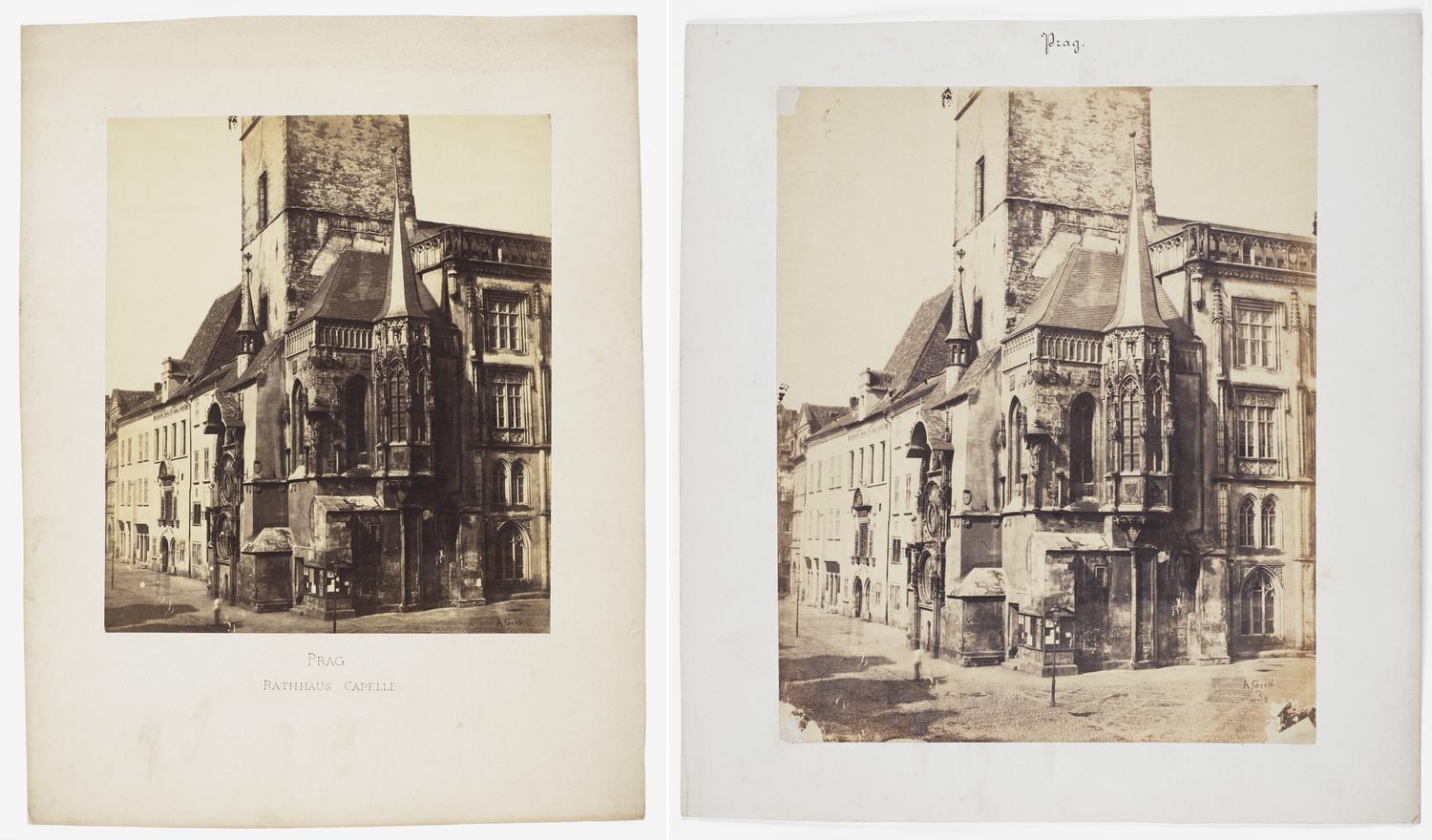

Fig. 2: The town hall in Prague’s Old Town, Andreas Groll, 1856, albumen print, 27 × 23 cm (photo), 42 × 32.3 cm (cardboard), Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. no. 572, photo: Vlado Bohdan / Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences.

Judging by the image content, the eight photographs could certainly be perceived as a precious souvenir of a trip to Bohemia from around 1860, whether from a tourist’s or an expert’s point of view; this becomes obvious particularly if we focus on the nicest of the eight copies (see Fig. 2). However, in the other “almost identical” cases of the series, particularly inv.no.579 (see Fig. 3), this interpretation would be hardly satisfactory.

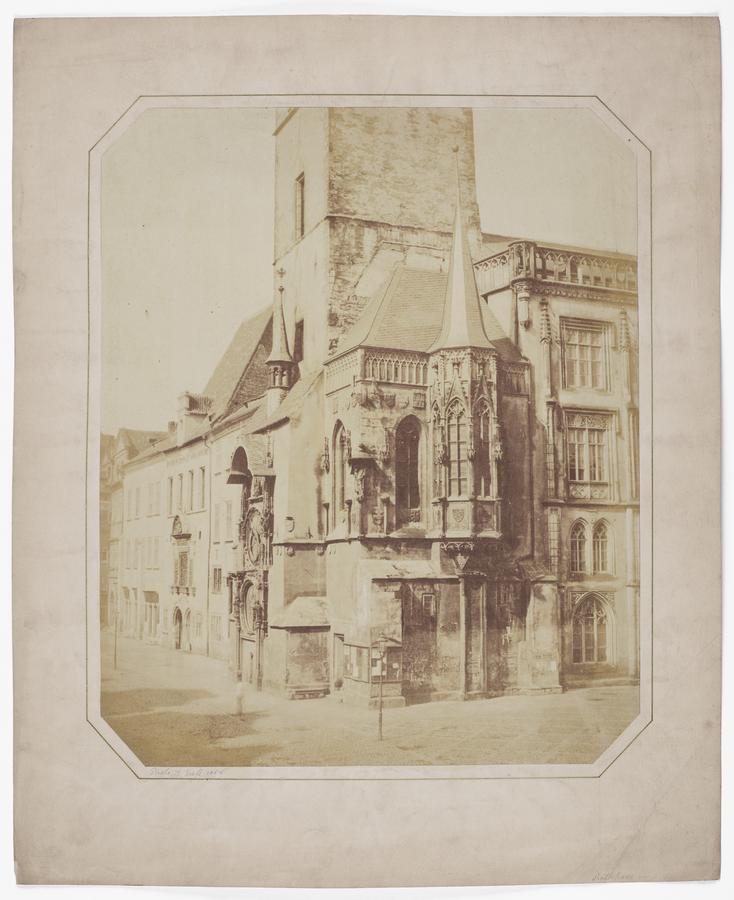

Fig. 3: The town hall in Prague’s Old Town, Andreas Groll, 1856, albumen print, 27 × 21.3 cm (photo), 27.8 × 22 cm (cardboard), Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. no. 579, photo: Vlado Bohdan / Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences.

There is no direct evidence of the photograph’s original purpose, such as bills, letters, or other documents which would lead directly to its initiator or commissioner. However, drawing on our present knowledge of Groll’s work, it is possible to presume that it was commissioned by the Austrian state office for the monument preservation called the Central Commission for Research and Preservation of Monuments (Zentralkommission zur Erforschung und Erhaltung der Baudenkmale, see Trnková 2015, 237–245). The office, established in Vienna in 1850, aimed first and foremost to identify, record, and bring attention to monuments which were—according to its criteria—worth studying and preserving (Frodl 1988). The city of Prague with its splendid late Gothic architecture was one of the places, along with Vienna and Kutná Hora (Central Bohemia), that received special attention.

Directed by the prominent figure of the Vienna School of Art History Rudolf Eitelberger von Edelberg (1817–1885),2 the Commission very soon engaged photographers (both laymen and professionals) to help document selected monuments. They were particularly engaged in recording the state of buildings prior to renovation. Groll, who from the very beginning of his career specialized quite systematically in architectural photography rather than portraiture, was among the very first photographers involved in the mission (Faber 2015a, 30–32, 53–57).

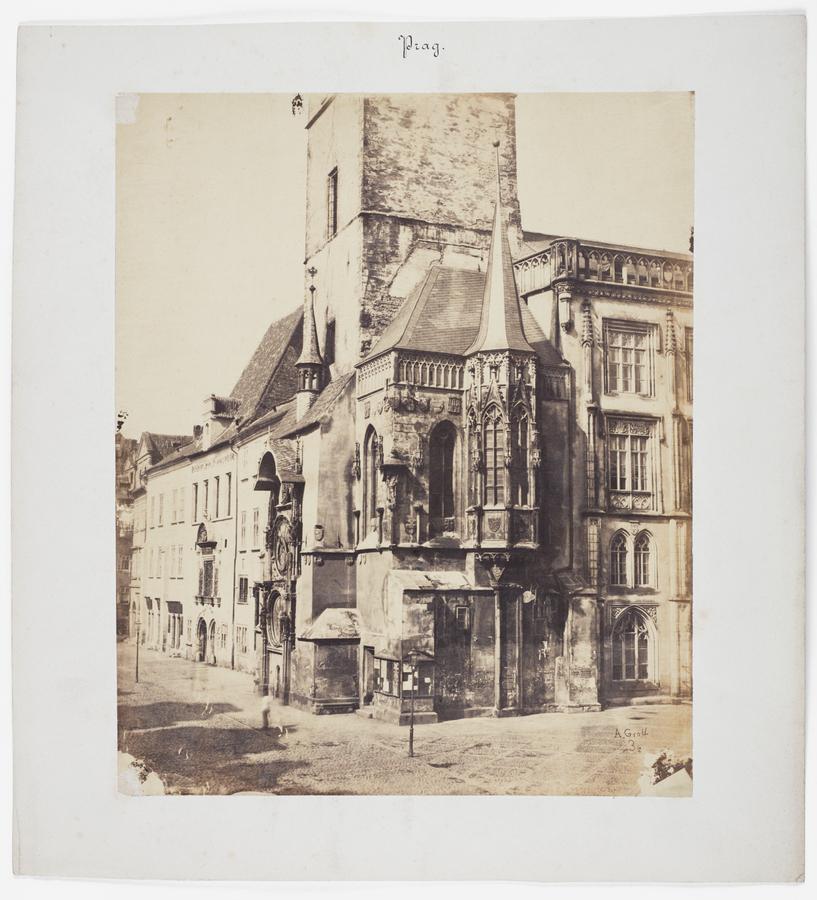

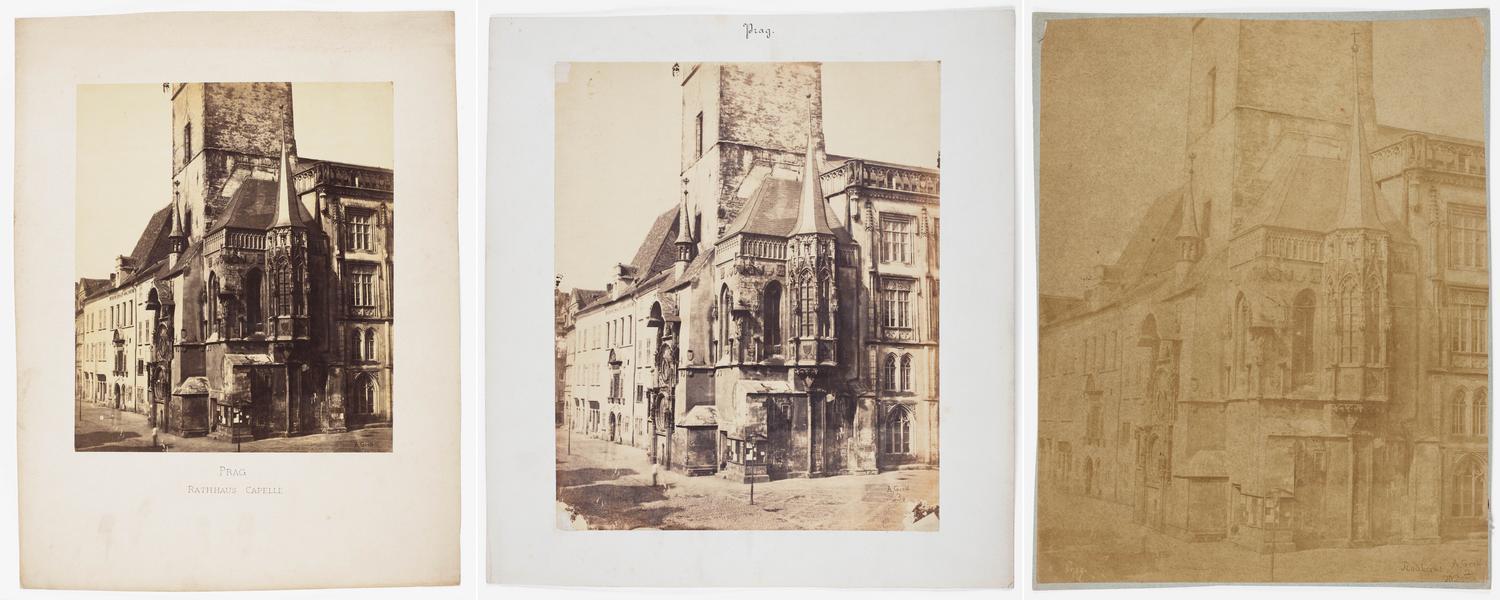

Fig. 4: “Photo A. Groll 1856.” The town hall in Prague’s Old Town, Andreas Groll, 1856, albumenized salted paper print, 28.4 × 23.2 cm (photo), 37.6 × 30.5 cm (cardboard), Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. no. 576, photo: Vlado Bohdan / Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences.

Judging by his own signature and the dates (see Fig. 4) inscribed in pencil on some of his works, Groll came to Prague for the first time to photograph the local medieval architecture no later than in 1856. As well as being a touristic attraction, the town hall was then also a subject of a long-lasting controversy between the Central Commission and the city administration, with each asserting an opposite conception of monument conservation and the building’s “architectural” future, particularly when it came to the southern frontage.3

In the early 1850s, the south wing (see the left-hand side of Fig. 2) was regarded as the most authentic part of the whole building complex, perfectly reflecting the Bohemian kingdom’s greatest eras of the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries. Consequently, the south wing became the central theme of discussions surrounding the building’s appropriate appearance. The municipality was pushing ahead the plan to adapt the building by emphasizing putatively “Bohemian”—and from a certain point in time also “Czech”—character. On the other hand, the state—in this case represented by the vicegerency, the Central Commission and its deputy Johann Erasmus Wocel—favored conservation of the building complex in its current state over reconstruction or the supposedly ideal adaptation.

Groll photographed this complex several times, from different angles and for more than one reason. On his visit in 1856, rather than on the most discussed and controversial south part of the building, he focused on the east wing and on the south-east corner, specifically the oriel window of the chapel (see Fig. 2) situated on the upper floor. The fact that Groll did not just take another picture of a popular tourist attraction is evident from the photographer’s stock catalog from 1864, which lists the photograph as the “Town hall chapel” (see Groll 1865). In the 1850s, oriel windows, usually the most authentic parts of Gothic buildings, attracted the particular attention of many archaeologists (historians and art historians), including conservators from the Viennese Central Commission for Research and Preservation of Monuments, and photography, next to more prevalent drawing and measuring, proved to be an excellent means to record such ornate and rather extensive architectural details. For similar reasons, the photographs were valued also by architects, particularly the proponents of historicism, for whom such an aide-mémoire never expired. This explains why there have been so many copies of Groll’s photographs preserved in local collections, especially in museums and institutions involved in monument care, as well as architects’ estates.

14.3 Eight photographs as individual objects

Without trying to impugn the importance of other aspects of Groll’s production, or to deconstruct the only recently revised narrative (Faber 2015b), I believe we need to look as closely as possible at the material issues connected to his doubles; just as we do when studying old masters’ paintings. I would like to draw attention to a few selected features that emerge when we examine the eight photographs as individual objects. They are capable of shifting ideas not only about Groll and photographic production in his era but also about the current photo collection management and our understanding of the history of photography in a much broader context. The following findings and comments are based primarily on careful and recurring observations of the photographs’ material qualities.4

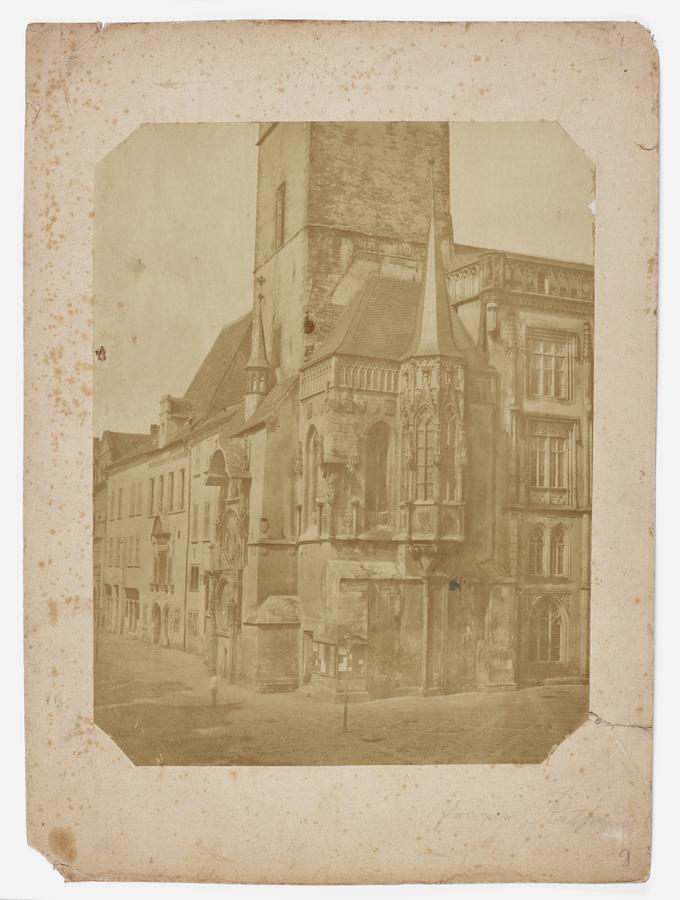

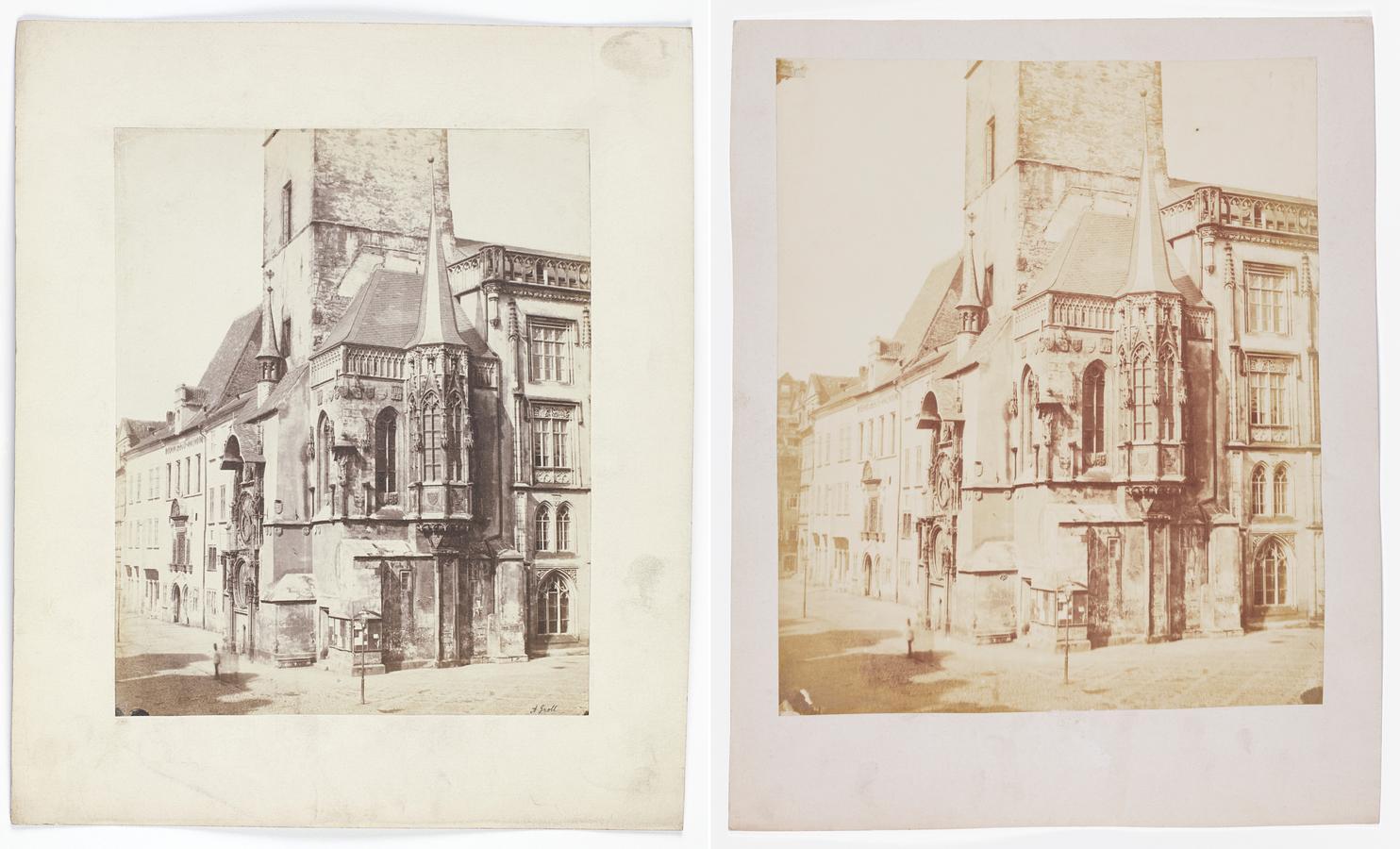

Fig. 5: The town hall in Prague’s Old Town, Andreas Groll, 1856, salted paper print, 27.8 × 22.5 cm (photo), 38 × 32 cm (cardboard), Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. no. 573, photo: Vlado Bohdan / Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences.

Fig. 6: The town hall in Prague’s Old Town, Andreas Groll, 1856, salted paper print, 28.3 × 24 cm (photo), 35 × 28.7 cm (cardboard), Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. no. 575, photo: Vlado Bohdan / Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences.

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. hicollage14_1

The first thing we should look into is the negative. Yet, here, we have to do so by means of the positives because the negative itself is missing, as is often the case. Analyzing the details in all images carefully, we realize that two photographs (see Figs. 5 and 6) in our series were, in fact, printed from a different negative to the rest. This is very clearly evident from the shadows and even more so from the fuzzy, ghost-like figure of a guard standing in front of the town hall; incidentally, these “ghosts” (compare Fig. 2 and 5 in Hyperimage) first sparked my interest in the series. Knowing for certain that Groll exposed—quite expectedly—more than one negative here, we become less prone to believe to the rather common idea of a photographic genius traveling a long way to Prague and climbing up to the top floor of a building with all his heavy photographic equipment to produce just one perfect shot of the town hall.

Another point concerning one of the two negatives—let’s label it “A”—is the complete fuzziness of photograph no. 575 (see Fig. 6). Without being able to see its clearly sharper “twin” image (see Fig. 5) printed from the very same negative, we would tend to see it as the rare calotype rather than a salted paper print from a glass plate negative, which was much more common in Central Europe. The only explanation I can offer here is careless handling of the light sensitive material while printing the positive. Thus, neither is a calotype; one of them was just printed in a slapdash manner.

Other items capable of breaking the “linearity” and traceable in the negative through positives are grit-like stains (see Fig. 4) clearly visible in the bottom right-hand corner of each of the six prints made from the negative “B”. These are most apparent in photograph number 576. This could suggest that the prints, although authentic and signed by the author, might have been produced from a copy negative and not from the original glass plate that Groll exposed in his camera from across the street. In the era of the collodion wet plate process, in particular travelling photographers like Groll were struggling to reduce their costs and alleviate physical hardship by creating a series of “master positives” right on the spot and then “recycling” the expensive glass plate for another shot.

Fig. hicollage14_2

Fig. hicollage14_3

Fig. hicollage14_4

What is perhaps more striking than the details, however, are the differences in the overall appearance of each photograph that may reflect the quality of printing and “postproduction,” and also how the material was treated throughout the next 15 or 16 decades. At first sight, the photographs vary in technology: there are two salted paper prints (see Figs. 5 and 6) of two very distinct colors, three albumenized salted paper prints (compare Fig. 4 with Figs. 7 and 8 in Hyperimage), and three albumen prints (compare Figs. 2, 3 and Fig. 9 in Hyperimage). This implies very clearly a rather long interval between the production of the earliest and of the latest print that could be 15 years or even more: in the first few years of his career, Groll used salted paper; albumenized salted papers were applied for a short period of time in the late 1850s (around 1857–1859); and albumen prints were commonly produced from around 1860 up until the end of the photographer’s career in the late 1960s.

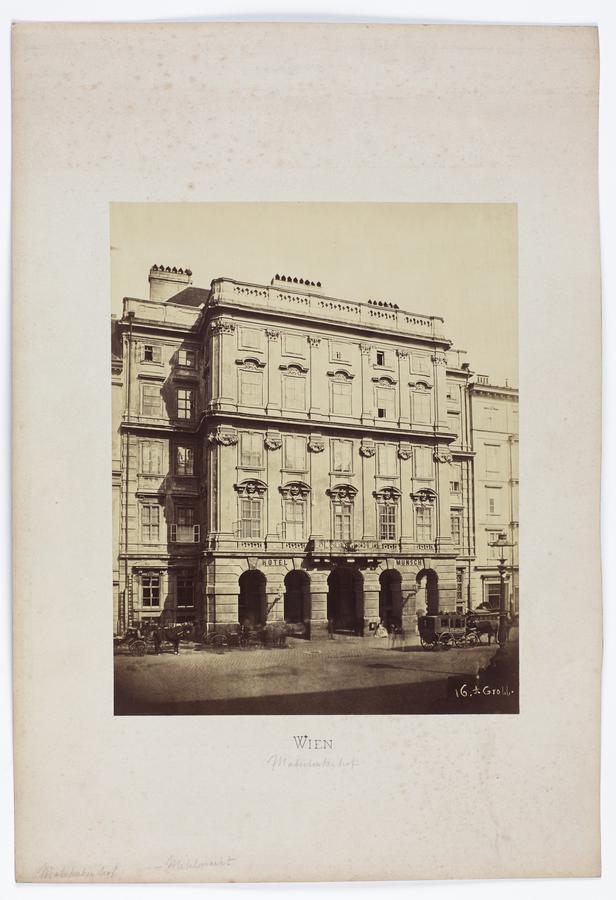

The mounting provides a great deal of information. We can learn a lot from its format, material, color, state of preservation, as well as inscriptions, whether these are made by the author or subsequently by an owner. From this perspective, one photograph inv. no. 572 (see Fig. 2) is particularly noteworthy. Today, it is filed within the series of Groll’s Prague views, specifically in the section regarding the town hall. However, the design of the title, which is inscribed on the front of the cardboard—“Prag Rathhaus Capelle,” suggests quite clearly that the print once used to be part of another coherent pictorial series. Its fragments can actually be found in other parts of the IAH photographic collection, mostly among prints categorized as “Viennese views.” They all have the same layout (see Fig. 10)—the same typography, same ink, a similar quality of print, and are made of the same material, as well as the width of the supporting layer being the same.

Fig. 10: Hotel Munsch, Vienna, Neuer Markt 5, Andreas Groll, after 1866, albumen print, 28.4 × 22.3 cm (photo), 47.3 × 32.3 cm (cardboard), Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. no. 697, photo: Jitka Walterová / Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences.

Fig. hicollage14_5

Fig. hicollage14_6

Fig. hicollage14_7

The only significant difference is the current height of the mounting board. On closer inspection, we can see that the Prague photograph, which used to be part of the same collection as the Viennese views, was for some reason later cropped at the top (compare Fig. 2 to Fig. 10 in Hyperimage). Perhaps this was because of a new owner, or a change to the cataloging system, but definitely due to a need to place this photograph—unlike the Viennese views—in another, much smaller box. This link, detected between the Prague photograph and the Viennese veduta, enables us to identify their former owner (probably the very first one): some of the photographs—or, more specifically, their mount boards—carry handwritten notes and references that lead to the Czech architect Josef Schulz (Noll 1992). Very few people in this region had a better opportunity and reasons to build up their own collection of photographic samples than Schulz: not only was he wealthy enough to purchase photographs from specialized dealers and professional photographers, but from his twenties onward, he also took photographs himself. The “fitted” typography as well as numerous breaks visible on many albumen prints from his collection suggest that Schulz, despite his financial means, favored purchasing cheaper loose prints and having them mounted afterwards over buying rather luxurious, nicely cut and mounted pieces (see Fig. 4) possibly with a photographer’s signature.5

All this, together with appropriate handling and high quality of the print itself, explains why the photograph inv. no. 572 has been so well preserved, unlike the last piece of the Prague series; this image has almost disappeared (see Fig. 3).6 (Speaking about the latter, it should be noted that the whole image—more precisely the architecture—was, for unknown reasons, additionally outlined in pencil.)

The inscriptions referring to the authorship and production are another most relevant source of information, along with image details, mounting, and inscriptions referring to the owner. Two of the eight prints in question were signed “A. Groll” in pencil (see Figs. 4 and 5 in Hyperimage) and thus practically authorized by Groll after being mounted on a standard mount board. Three other photographs, which were quite clearly printed later, received his signature through the negative. This makes them truly interesting, because as such they are carrying more than just a signature. In two cases the inscription reads “A. Groll 3” (see Fig. 2 and Fig. 9 in Hyperimage). But in the one picture, the number “3” is crossed off and replaced by a number “202” together with the word “Radhaus”7 (see Fig. 3). Judging by many other similar cases (including works by the same author), both numbers—“3” and “202”—should theoretically correspond to an item listed in a photographer’s stock catalog. Yet none of them coincide with the only known issue of the catalog from 1864, in which the only photograph matching such an image bears the ordinal number “54” and refers to the negative number “162.” The most likely explanation seems to be the existence of (an)other catalog(s) or reference system(s), unknown today.

A story on its own, when it comes to Groll, is the retouching of negatives and printed copies, as well as other secondary image improvements, such as masking. From a researcher’s point of view, it is precisely this field that makes Andreas Groll’s work so special—the perfect material to learn about nineteenth-century photographic production in a complex manner. Due to considerable fading of his works, all efforts to hide technical mistakes are now foiled, as the dark and almost fadeless retouching ink reveals and sometimes even emphasizes all the imperfections, including the tiniest ones or those caused by the photographer himself. There are plenty of striking examples, particularly when we look at later albumen prints, but I would like to point out just one of them—once again, the last picture in the Prague town hall series. Although accomplished quite carefully, the retouching clearly did not fulfill its purpose in the long term perspective: as a result of this, we can easily see that this print was made from a broken glass plate negative (see Fig. 3). This means that this is the latest piece depicting the town hall that is known at present, if not even the last one produced.8

14.4 (Re)collection #1

It has already been mentioned that the time span between production of the earliest and the latest prints could be up to twenty years. This is quite logical, considering the timeless subject—a historic building. There is no doubt that Groll was able to and perhaps even requested to reuse the negatives, which were originally commissioned (and paid for) by the Central Commission, in his next business. Quite legally, he could go on with printing and selling some of the photographs and series on his own to other clients until the end of his career (cf. Faber 2015a, 74). Photographs like those from Prague were printed in hundreds, if not in thousands, and now can be found in many public and private collections.

The eight photographs of the town hall, now in the collection of the Institute of Art History, came together only in the 1920s–1940s. The man behind it was the Czech art historian Zdeněk Wirth (1878–1961) who had a special interest in nineteenth-century photography. Wirth started his career around 1906 and very soon, as well as being an employee of the Museum of Applied Arts in Prague, he was appointed by the Viennese Central Commission as a regional conservator in Bohemia (Uhlíková 2010). After the break-up of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, he began to become a key figure in the fields of art-historical topography, monument preservation, and cultural administration in Czechoslovakia. He elevated his status even more in 1923, when he became the head of the cultural section at the Czechoslovak Ministry of Education.

Despite his extensive involvement in the state cultural administration, Wirth was able to continue with his own research, often reaching beyond mainstream areas.9 Sometime in the 1920s–1930s, in addition to other research subjects that were rather unorthodox at that time, he became interested in the history of photography, and even within this then marginal field, he selected rather obscure topics, including Andreas Groll. Unfortunately, we do not know what exactly triggered his interest in photography history and when. If it were in the 1930s, he might have been inspired by the work of his Viennese peer Heinrich Schwarz (born in Prague, 1894–1974)—the author of the very first monograph on David Octavius Hill (Schwarz 1931). What is very clear is that Wirth’s research into the history of photography culminated around 1939/1940: firstly, with an extensive exhibition on the photography’s sesquicentennial, and secondly, with a monograph study on Groll, which remained the only publication about this photographer right up until 2015 (Wirth 1939–1940, 361–376; 1939).

Wirth’s research into nineteenth-century photography drew greatly from a vast photographic collection which he was able to put together owing to his knowledge, contacts, and influence at the highest political level. Throughout his life, Wirth assembled over one hundred thousand negatives and positives, more than six hundred of which could be associated with Groll.10 He also identified many more photographs in other collections, both in Czechoslovakia and elsewhere.

14.5 (Re)collection #2

After Wirth’s death in 1961, a large part of the photographic collection, along with other visual and written material he gathered throughout his long career, was assigned to the IAH. Arousing little interest, it remained intact there until 2008—uncataloged and mixed with other items such as books, manuscripts, correspondence, and diaries. It became a true sediment of visual knowledge (see Caraffa 2011, 12), a classic example of a forgotten photographic archive with all its attributes, including the cellar as a storage space and the overflow caused by a broken pipeline.

In 2007, the IAH directorate decided to establish an autonomous photographic collection by selecting all photographs from Wirth’s and other art historians’ estates held by the Institute. Up until this point, the photographs “were just there”—as Elizabeth Edwards said concisely with reference to a similar case11—almost untouched for nearly five decades. In an effort to make the photographs known and eventually accessible, very courageous yet rather wild reorganization erupted. Within a short period of time, most of the photographic material was sorted out, removed from boxes, and separated from the rest of the archive.12 The original boxes’ registration numbers, now written in pencil on the back of each photograph, are the mementos of the previous system. In accordance with traditional research interests and methodological approaches of the IAH, all photographs then began to be organized topographically.

Another survey was started only a year later, in summer 2008, now led by a photo historian and aimed to look not only at images but also at photographs as such, and in a much more complex way. For the first time, the photographs from Wirth’s and other art historians’ archives administered by the IAH began to be looked at and actually managed as an autonomous, full-fledged photographic collection (Trnková 2010). Among more than one hundred thousand prints, negatives, and transparencies, over six hundred items connected to Groll emerged. Along with original salted paper and albumen prints, later copies on gelatin paper were also identified, apparently corresponding to Wirth’s publications on the history of photography.

The “decontextualization” accomplished in 2007 completely disrupted the system, which was originally set up by Wirth. Naturally, this also affected Groll’s photographs now scattered over the whole collection, in accordance with the new topographical criteria. But it was not only in the case of Groll that photo-historical value seemed to prevail over art-historical. Rather than tools of art-historical topography, as they had been understood for many decades, the photographs were now recognized as key components of Central European history of photography and so it was decided to put all of Groll’s photographs together. It only transpired later that they were actually put back in the order in which they had been arranged while in Wirth’s possession. With this “once and future” configuration, other relations emerged which have inspired new research topics, including the “duplicates.” Their amount was striking from the very beginning and this simply could not have been ignored.

Here, I would like to mention the Viennese scholar Monika Faber, whose lifelong interest in Groll was known to most of her colleagues by then. She first came to Prague to inspect the “newly found Grolls” in 2009. Amazed at the number of duplicates, triplicates, and suchlike, she said “Why do you have so many?! Let’s swap!” Of course, it was just a hyperbole—an idea impossible to put into practice; and not just because she was a curator of the photographic collection of the Albertina in Vienna at that time. Her spontaneous reaction spoke for itself. Later on, in our joint research on Groll, the duplicates and other multiple copies turned out to be in many ways an irreplaceable source of information about Groll and his work, and also a perfect means to learn about the photographic production of the 1850s and 1860s and not just with regard to Vienna or Prague.

14.6 The need for duplicates

The eight photographs by Groll show how far duplicates can broaden our knowledge of the history of photography, whether it regards one’s photographic career, photographic technology, use and treatment of photographs, conservation of photographic material, collection management, or other relevant aspects. In this case, it also tells a lot about transformations in the relationship between the history of photography and the history of art. In conclusion, I would like to touch upon a few points and ideas which seem most relevant in this specific context.

First, I would like to point out that by happy coincidence, Wirth’s archive was opened in the “era of the photographic object” and a thriving interest in materiality in photography. Had it been earlier, for example in the 1970s and 1980s when the research aimed almost exclusively at the “image,” the “supposedly same” doubles would have been unlikely to survive; particularly at the institute cherishing artistic value of unique pieces above all. In contrast, today’s interest in the history of photography is much more favorable to such “presumably neutral” objects as duplicates.

My second point bears on two crucial concepts bound with photography since its very beginning: reproducibility (or multiplication) and seriality, which are now both undergoing a form of revival within the photographic discourse. These concepts are largely discussed with reference to the omnipresent digitalization, but they are in fact essentially related to the aforementioned materiality. I do not mean to imply that digitalization is in conflict with materiality. Quite the contrary, they can work together: the materiality owes a great deal to digitalization and high resolution of images because the technology has compensated for a conventional magnifying glass, which used to be a tool needed for scanning photographs but now it is utilized routinely only by photo conservators and very little by photo-historians.

Another thing one that can be seen very easily through the duplicates today is how far the IAH collection system, which was set up in 2008–2009, has been affected by our preferences for image beauty, although the primary concepts are topography and the photograph as an object. If the duplicates had been cataloged later or known better, another permutation might have been considered. Most probably, it would have been the chronology (see Fig. 12) instead of the appeal (see Fig. 11).

These are just a few reasons why the questions “Why do you have so many?” or “When to discard the doubles?” are quite irrelevant. Nonetheless, these questions will be coming back like a boomerang, as we will always, at least subconsciously, favor the image over the object; no need to mention saturation of the store rooms, which is a common excuse for eliminating those identical pictures. All this is despite their communicative value, charm, familial relationship (Riggs 2016, 269), own history of each of them, or simply our natural fascination for “twins” or, here, for “octuplets.”

Fig. 11: The series of eight photographs of the town hall in Prague’s Old Town by Andreas Groll, 1856, Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. nos. 572–579.

Fig. 12: The series of eight photographs of the town hall in Prague’s Old Town by Andreas Groll, 1856, Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. nos. 575, 573, 576, 577, 578, 572, 574, 579.

14.7 Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Monika Faber from the Photoinstitut Bonartes in Vienna, whose research into nineteenth-century photography, particularly into the work of the Austrian photographer Andreas Groll, has been a great inspiration to me. Endless discussions with her inspired many of my thoughts and ideas presented in this essay. Also, my thanks go to Jens Gold from the Preus Museum in Horten, who, likely unwittingly, first sparked my interest in a specific series of eight photographs by Groll, which are in the limelight of this study.

14.8 List of figures

• Fig. 1: The series of eight photographs of the town hall in Prague’s Old Town by Andreas Groll, 1856, Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. nos. 572–579, photo: Petra Trnková.

• Fig. 2: The town hall in Prague’s Old Town, Andreas Groll, 1856, albumen print, 27 × 23 cm (photo), 42 × 32.3 cm (cardboard), Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. no. 572, photo: Vlado Bohdan / Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences.

• Fig. 3: The town hall in Prague’s Old Town, Andreas Groll, 1856, albumen print, 27 × 21.3 cm (photo), 27.8 × 22 cm (cardboard), Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. no. 579, photo: Vlado Bohdan / Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences.

• Fig. 4: The town hall in Prague’s Old Town, Andreas Groll, 1856, albumenized salted paper print, 28.4 × 23.2 cm (photo), 37.6 × 30.5 cm (cardboard), Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. no. 576, photo: Vlado Bohdan / Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences.

• Fig. 5: The town hall in Prague’s Old Town, Andreas Groll, 1856, salted paper print, 27.8 × 22.5 cm (photo), 38 × 32 cm (cardboard), Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. no. 573, photo: Vlado Bohdan / Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences.

• Fig. 6: The town hall in Prague’s Old Town, Andreas Groll, 1856, salted paper print, 28.3 × 24 cm (photo), 35 × 28.7 cm (cardboard), Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. no. 575, photo: Vlado Bohdan / Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences.

• Fig. 7 (in Hyperimage only): The town hall in Prague’s Old Town, Andreas Groll, 1856, albumenized salted paper print, 28.7 × 22.9 cm (photo), 38.6 × 29 cm (cardboard), Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. no. 577, photo: Vlado Bohdan / Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences.

• Fig. 8 (in Hyperimage only): The town hall in Prague’s Old Town, Andreas Groll, 1856, albumenized salted paper print, 27.8 × 22.6 cm (photo), 33.3 × 25 cm (cardboard), Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. no. 578, photo: Vlado Bohdan / Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences.

• Fig. 9 (in Hyperimage only): The town hall in Prague’s Old Town, Andreas Groll, 1856, albumen print, 29.3 × 24 cm (photo), 36 × 33 cm (cardboard), Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. no. 574, photo: Vlado Bohdan / Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences.

• Fig. 10: Hotel Munsch, Vienna, Neuer Markt 5, Andreas Groll, after 1866, albumen print, 28.4 × 22.3 cm (photo), 47.3 × 32.3 cm (cardboard), Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. no. 697, photo: Jitka Walterová / Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences.

• Fig. 11: The series of eight photographs of the town hall in Prague’s Old Town by Andreas Groll, 1856, Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. nos. 572–579.

• Fig. 12: The series of eight photographs of the town hall in Prague’s Old Town by Andreas Groll, 1856, Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences, collection of photographs, inv. nos. 575, 573, 576, 577, 578, 572, 574, 579.

14.9 References

Brückler, Theodor and Ulrike Nimeth (2001). Personenlexikon: Zur Österreichischen Denkmalpflege. Vol. 7. Horn: Berger.

Caraffa, Costanza (2011). From Photo Libraries to Photo Archives: On the Epistemological Potential of Art-Historical Photo Collections. In: Photo Archives and the Photographic Memory of Art History. Ed. by Costanza Caraffa. Berlin and Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 11–44.

Eitelberger, Rudolf von (1863). Der Kupferstich und die Fotografie. Zeitschrift f ür Fotografie und Stereoskopie 7:123–126.

Faber, Monika (2015a). ‘… mit aller Kraft auf die Photographie verlegt …’: Annäherungen an das Berufsbild eines frühen Fotografen. In: Andreas Groll: Wiens erster moderner Fotograf. 1812–1872. Ed. by Monika Faber. Salzburg: Fotohof Edition, 27–95.

– ed. (2015b). Andreas Groll: Wiens erster moderner Fotograf. 1812–1872. Salzburg: Fotohof Edition.

Frodl, Walter (1988). Idee und Verwirklichung: Das Werden der staatlichen Denkmalpflege in Österreich. Wien, Köln, and Graz: Böhlau.

Groll, Andreas (1865). Verlags-Catalog von Andreas Groll, Photograph in Wien. Vienna.

Lachnit, Edwin (2005). Die Wiener Schule der Kunstgeschichte und die Kunst ihrer Zeit: Zum Verhältnis von Methode und Forschungsgegenstand am Beginn der Moderne. Vienna: Böhlau.

Noll, Jindřich (1992). Josef Schulz 1840–1917. Prague: Národní galerie.

Riggs, Christina (2016). Photography and Antiquity in the Archive, or How Howard Carter Moved the Road to the Valley of the Kings. History of Photography 40(3): 267–282.

Roháček, Jiří and Kristina Uhlíková, eds. (2010). Zdeněk Wirth pohledem dnešn í doby. Prague: Artefactum.

Schlosser, Julius von (1934). Die Wiener Schule der Kunstgeschichte: Rückblick auf ein Säkulum deutscher Gelehrtenarbeit in Österreich. Mitteilungen des Instituts f ür Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 13(2):141–228.

Schwartz, Joan M. (1995). We Make Our Tools and Our Tools Make Us: Lessons from Photographs for the Practice, Politics, and Poetics of Diplomatics. Archivaria: The Journal of the Association of Canadian Archivists 40:40–74.

Schwarz, Heinrich (1931). David Octavius Hill: Der Meister der Photographie. Leipzig: Insel-Verlag.

Trnková, Petra, ed. (2010). Oudadate Pix: Revealing a Photographic Archive. Prague: Artefactum.

– (2015). Archäologischer Frühling: Aufnahmen historischer Baudenkmäler in Böhmen. In: Andreas Groll: Wiens erster moderner Fotograf. 1812–1872. Salzburg: Fotohof edition, 237–245.

Uhlíková, Kristina (2010). Zdeněk Wirth, prvn í dvě životn í etapy (1878–1939). Prague: Národní památkový ústav.

Wirth, Zdenĕk (1939–1940). První fotograf Prahy. Uměn í 12:361–376.

Wirth, Zdeněk, ed. (1939). Sto let česk é fotografie 1839–1939. Prague: Umělecko-průmyslové Museum.

Footnotes

With the growing interest in “duplicates” that was observed at the Photo-Objects conference in Florence in 2017, we can expect detailed discussion about terminology, too.

Schlosser 1934, 155–159; Brückler and Nimeth 2001, 58–59; Lachnit 2005. Eitelberger was one of the front promoters of applying photography in art-historical, archaeological and museological practice, see Eitelberger 1863, 123–126.

Groll’s involvement in the discussions is highly unlikely, considering his social status and his field of knowledge.

Unfortunately, I have not had the opportunity to apply more sophisticated methods, such as XRF or FTIR analyses.

Judging by the high standard of the mounting, he must have commissioned a professional mount maker.

The image most probably deteriorated due to poor quality of the mounting material, in particular the adhesive or the supporting layer.

Misspellings like this, notoriously occurring on Groll’s photographs, are very likely due to the author’s lack of proper education, see Faber 2015a, 32–33.

In later years, this practice was in fact nothing unusual in Andreas Groll’s enterprise.

Although he was a graduate of Charles University in Prague in history and bohemistics, Wirth’s practice was more akin to the Vienna School of Art History.

To this day, it remains the second largest collection of photographs by Andreas Groll.

On the IAH archive and its other collections, see Roháček and Uhlíková 2010.