7.1 A fortunate find

A visit to the photo archive at the Kunsthistorisches Institut (KHI) in Florence’s Via dei Servi. The year is 2014. I am working on Photographic Interleavings and conducting research on self-reflective picture-in-picture examples from the field of photography. For this purpose, I take down from the shelf the slipcase dealing with the architecture of the Palazzo Capponi-Incontri in Florence, the former home of the KHI’s photographic collection. I find exterior and interior views of the building. This architectural shell of the photography collection found its way as a photographic representation into the archival box, which in turn makes up, together with other boxes, the collection that the institute’s Fototeca, or photo library, contains in its interior: a kind of inward eversion has occurred, and a mise en abyme of the triad of representation, photographic objects, and their containers.

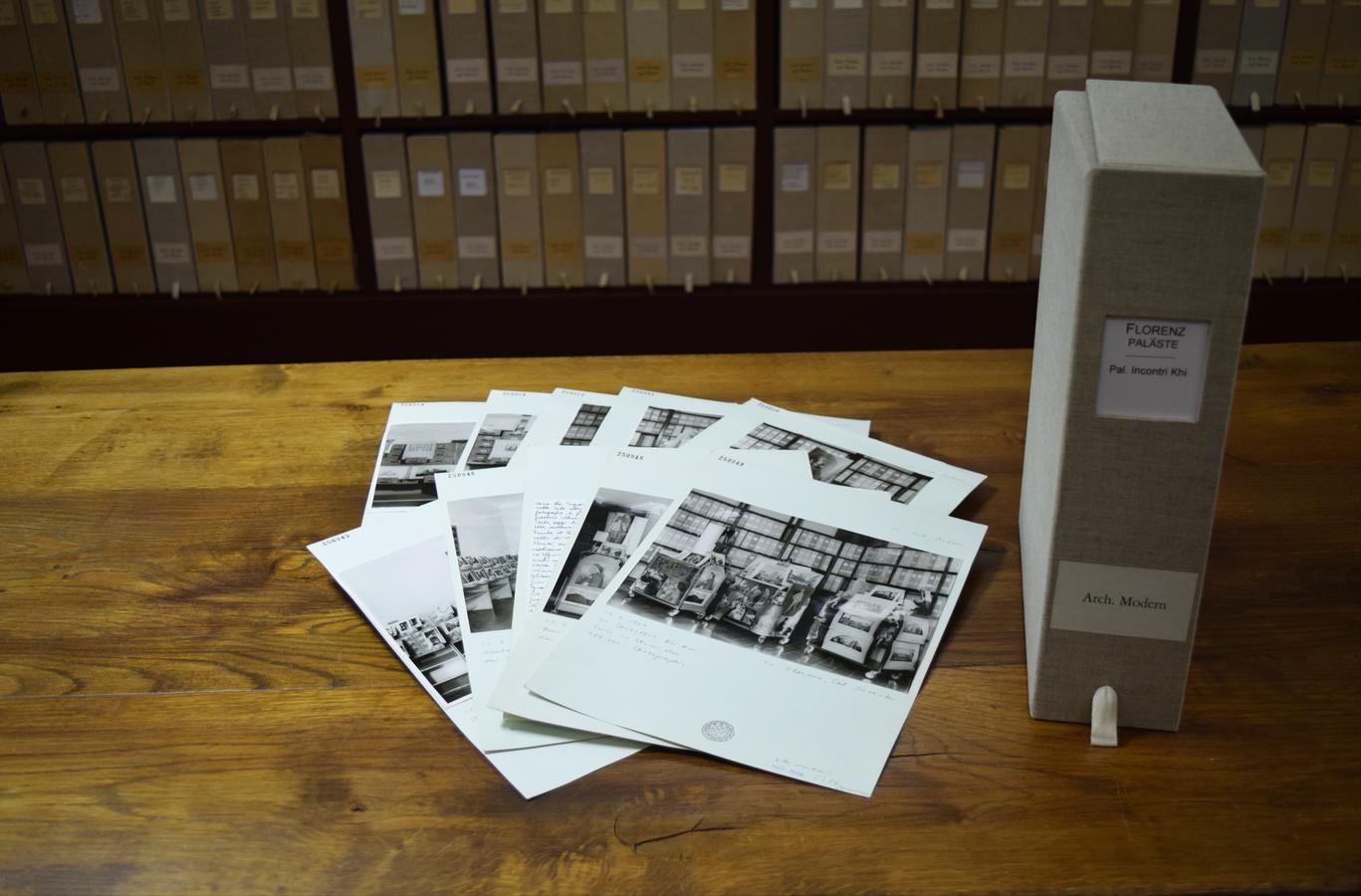

Fig. 1: Box with the Photographs of the Triumph of Photography in the Fototeca, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

Aside from this architectonic self-representation of the Fototeca situated in the official archive that is open to the outside world for the purpose of scholarly research, there is another more historiographic and internal form of self-representation. It is found in a plastic binder with assorted photographs taken at special occasions that took place at the KHI Florence. They often involve celebrations or the visits of important people, all unrelated to everyday life at the institute. The general public does not have access to this binder, which in its own way can be equated to a random collection of pictures that is close to the genre of the family photo album.

However, my fortunate discovery, which raised my questions concerning photographic interleaving onto a different plane and shifted my perspective to problems of materiality, the objectness and handling of photography and archives, was made in the above-mentioned official slipcase. It contained a bundle of photographs that, at first sight, did not appear to directly correspond to the category of the interior or exterior architecture of the Palazzo Capponi-Incontri. In fact, it seemed in some ways to have more in common with a private photo album dealing with the history of the Kunsthistorisches Institut. What I found were ten black and white photographs mounted on cardboard (see Fig. 1). They were taken on June 20, 1969 at the in-house celebration marking the acquisition of the institute’s 250,000th photograph.

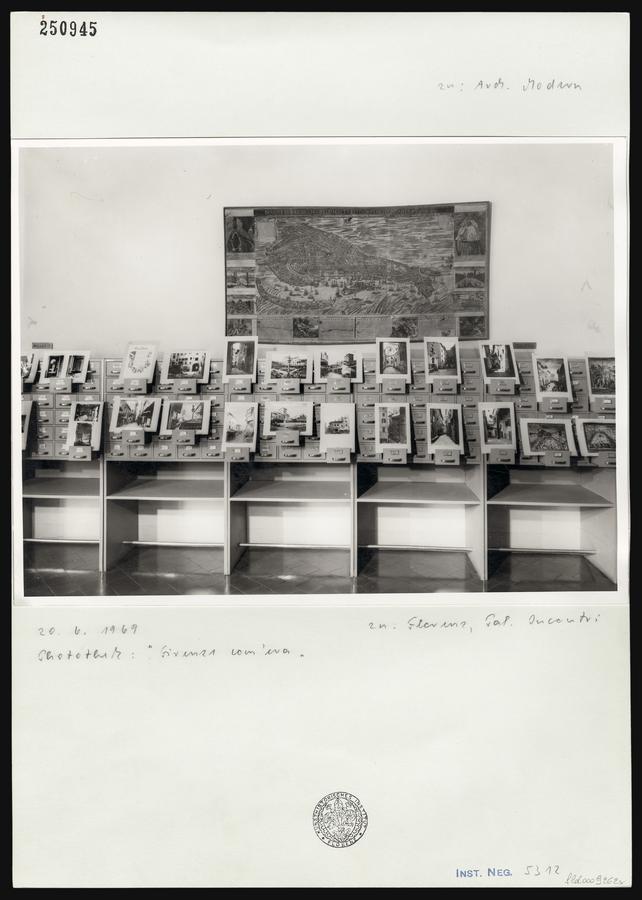

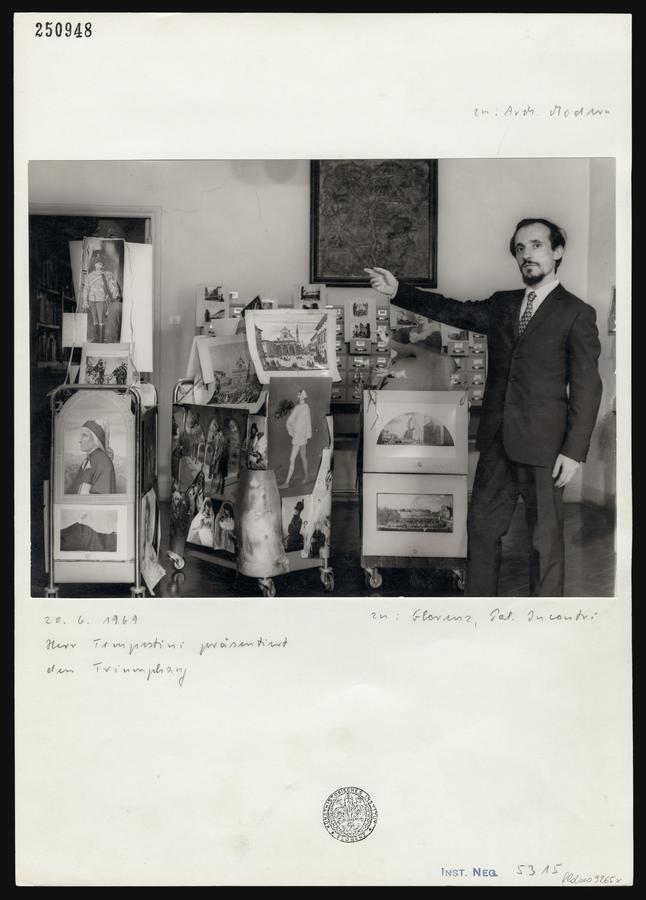

Fig. 2: Exhibition of mounted photographs of the Triumph of Photography in the Fototeca: Firenze com’era, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

We see with these photos two ephemeral presentation modalities used to celebrate a selection of the Fototeca’s photos. In both cases, we are confronted with picture-in-picture representations that, however, vary in terms of space-time structure and inform us about different ways of dealing with photographic objects.

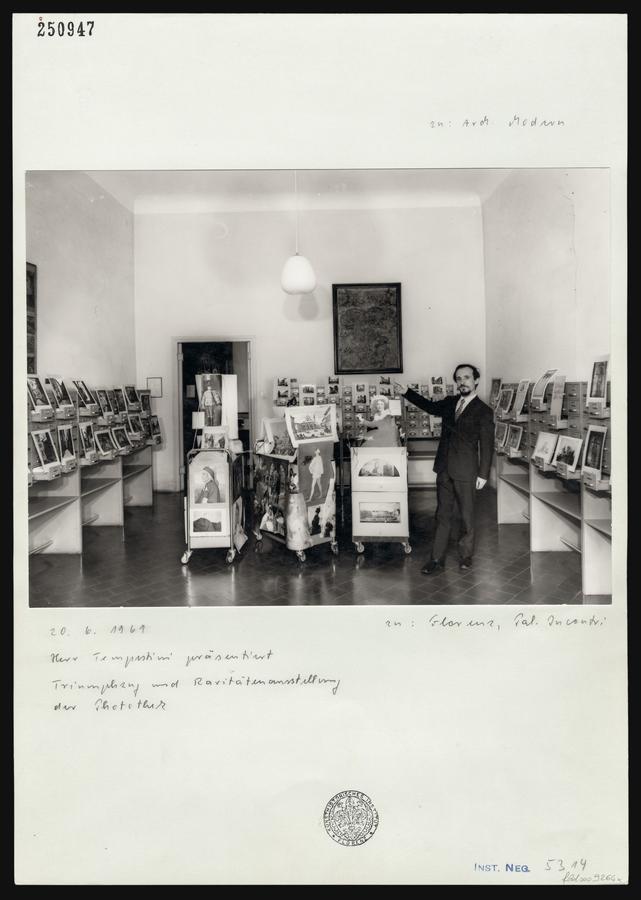

Fig. 3: Anchise Tempestini presenting the Triumph of Photography in the Fototeca, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

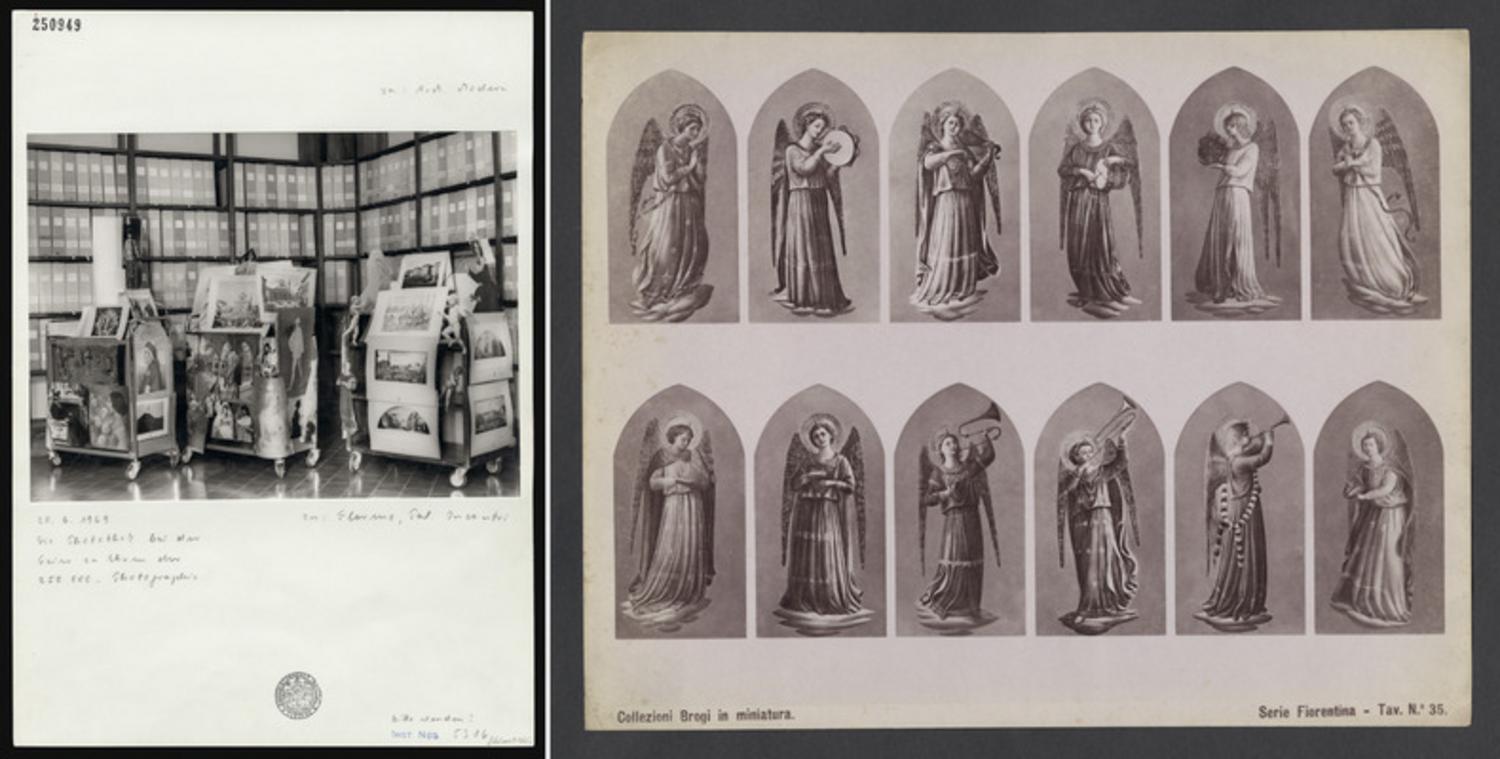

The first group (see Fig. 2) concerns photographs from the collection’s holdings that were filed in open drawers of the Fototeca’s catalog cabinets. According to the labels inscribed on the cardboards of the mounted photos by the then head of the photograph collection, Dr. Irene Hueck, they involve Sehenswürdigkeiten, that is, points of interest or historic sites, Rariora und Curiosa, that is, rarities and curiosities, as well as Ehrwürdige Aufnahmen, that is, venerable photographs of the archive. It cannot be established from the photographs whether these largely architectonic depictions pertain to the categories of the reference catalog or whether they were randomly filed there. However, their unusual presentation in the drawers of the wooden cabinets and within the neutral space of the catalog room integrates them into a visual order suggesting systematic classification, regularity, and clarity through the frontality with which the prints are lined up in a paratactic structure opposite the camera. Based on the arrangement of paintings in museums, at the same time, it fits in with registry and reference structures. In other words, it primarily addresses our comparative and systematic sense of sight. The presentation also underscores the two-dimensionality of a photograph as a plane and static object in front of us, suggesting to the beholder a contemplative or inquiring observation. Summa summarum and as a picture-in-picture, the whole arrangement makes us reflect upon the prevailing archival and museological systematization as a normative code of reception.

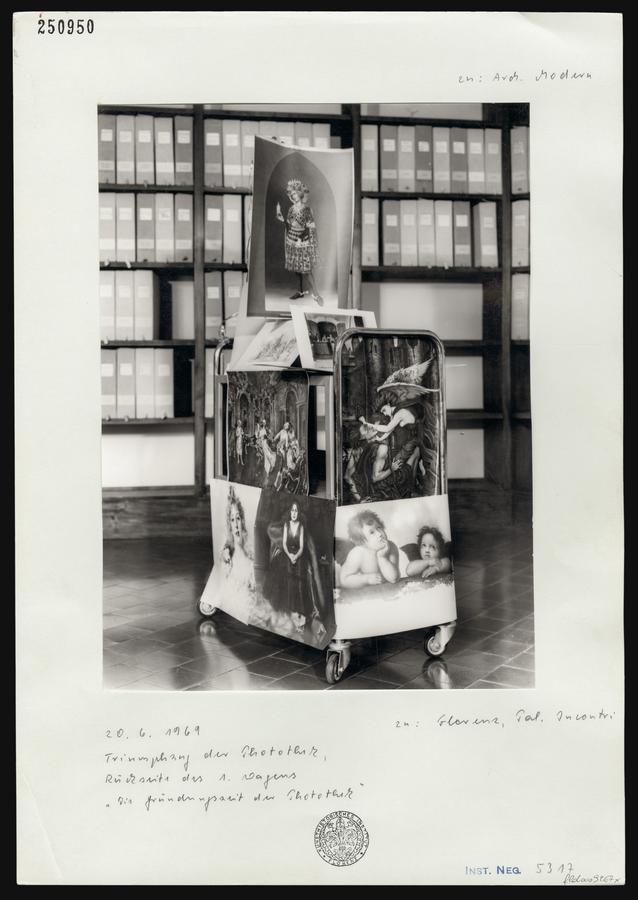

By contrast, the second manner of dealing with the photographs in the Florentine archive (see Fig. 3) involves the festive procession format of the type that enjoyed great popularity in Florence during the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Photos from the archive were mounted on three carrelli, the trolleys used to transport books in the library and photograph boxes in the Fototeca,1 and then paraded across the entire length of the Fototeca on the second floor of the Palazzo Capponi-Incontri past a small invited circle of “institute staff members, scholarship holders, and regular visitors.”2 The photos make the handling of the photographs comprehensible as an act of bricolage. They show that the pictures have been cropped, folded, pasted on top of each other and applied to the frames of the carrelli. Unlike their systematized formation in the catalog cabinets, the photos on the carrelli evoke a reception that is more in accordance with an imagined sense of touch. It directs our attention more to the three-dimensionality of the configurations that invoke a physical reenactment. In short, the photo sculptures of the Florentine procession with their character of an associative collage represent a haptic and affective individual access, that is, a “wild” approach to the archive.

Taking a closer look at the photos in this triumphal procession of photography, I would like to examine in particular the three central ways of dealing with the archive’s photos that they offer. These are actions of recombination, of setting in motion, and of performance. These primary means of handling the photo objects in turn bring about methods of displaying that recall the ars combinatoria of the assemblage, the kinesis of the procession and the performativity of theatrical declamation. My hypothesis is that it involves invitations for a playful handling of the photos that open up a meta-level of reflection about photographic objects as actors and agencies in the fields of archives, exhibitions, and performances. I also wish to show that this incentive for a “wild” approach to the photos has an explosive quality, jeopardizing and desacralizing both the official and unofficial instruction guidelines for the use of the photographic archive;3 or, put positively, that the triumphal procession of photography in the Fototeca blasts the boundaries of the archive to such an extent that it opens up for us paths of a non-intentional, ludic, artistic, and poetic means of dealing with the photo objects.

7.2 Assemblage and inset image: forms of material and the deictic autopoiesis of photography

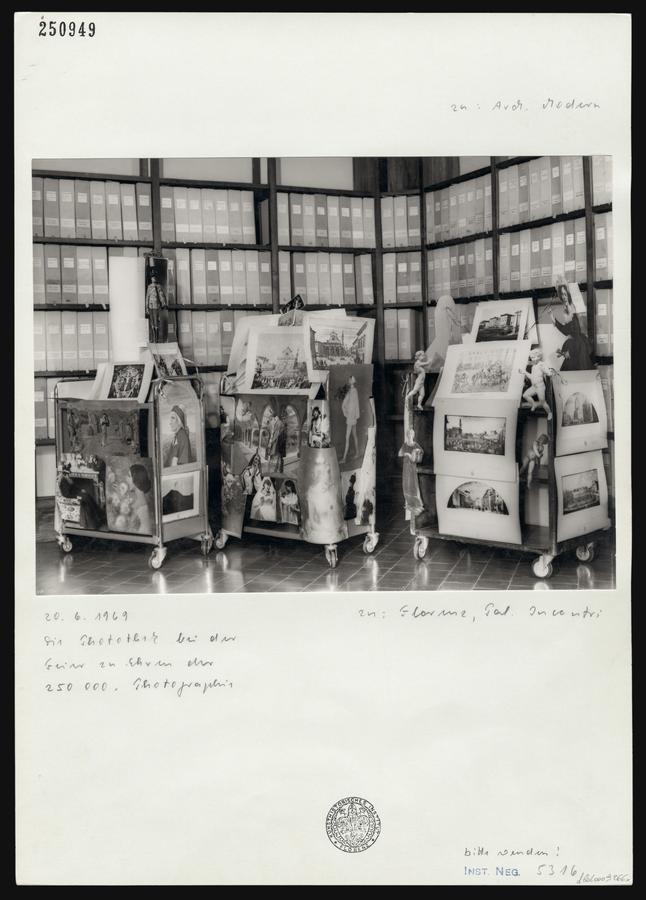

Fig. 4: Mounted Photographs of the Triumph of Photography in the Fototeca, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

If we take a closer look at the materials and pictorial contents of the three “processional wagons,” we notice how heterogeneous they are: the first wagon (see Fig. 4), dedicated to the Founding Time of the Fototeca, has a full-length picture of Umberto I at the top, Italy’s king during the very first years of the archive, then the large-format photographic reproduction by the Brogi company of the Dante portrait attributed to Giotto in the Bargello, Florence, and, at the foot of the carrello, a photograph of the active Mount Vesuvius, the 1906 eruption of which was one of its most powerful in 250 years. Also by Brogi, we see a very different genre on the side of the carrello, namely the reproduction of an elegiac portrait of a woman with a bouquet of flowers bearing the sentimental title Fior di Mestizia (Flower of Melancholy) that corresponds to the ideal of womanhood around 1900.

Fig. 5: The Triumph of Photography in the Fototeca: Wagon 1, Founding Time of the Fototeca, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

On the other side of the wagon (see Fig. 5), the reproduction of the struggle between an angel and a person possessed by the devil in the style of the Pre-Raphaelites is placed above the large-scale photograph of the winged cherubs at the bottom of the Sistine Madonna. With a kitsch touch, the putti appear to be observing the heroic scene from below, lending it a comic note. On the other side, two portraits of women from Brogi’s Gallery of Beauties encounter the moralizing genre painting of a boisterous dancing scene in an excessive Rococo style. Above them towers the isolated figure of one of the three Kings from Gentile da Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi in the Uffizi Gallery. What resembles wild potpourri is in fact only held together by the very loose ties to the Founding Time of the Kunsthistorisches Institut, as it says in the inscriptions of the photos on the cardboard.4

Fig. 6: The Triumph of Photography in the Fototeca: Wagon 2, Firenze com’era, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

No less heterogeneous are the materials and representations from the second wagon (see Fig. 6), which was concerned with Firenze com’era (Florence as it was). Crowned by an engraving by the Parisian Lemercier company showing a view of Florence as seen from the Porta San Niccolò is a large-format photograph of the sculpture hall in the Uffizi in the center, flanked by staged photos of folkloristic genre figures and masquerade scenes.

The other side also presents a mixture of different materials and genres (see the middle wagon in Fig. 4). An engraving of the Piazza Santa Croce on the occasion of the erection of the Dante statue on May 14, 1865 is to be seen above a large photograph of the cloisters at the monastery of San Marco. At the bottom, figures of a nun and folkloric women overlap the photo of the cloister while the de-contextualized full-length figure of Cimabue seems to be marching in the direction of the San Marco monastery on his left. Above it towers an engraving of the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata. At the edges of the carrello, large and mid-format Brogi depictions of women with titles such as The Spring of Life or Interrupted Reading overlap Cimabue’s portrait. The dense interweavings of these large and small, cropped and bent photographs evoke a general narrative that at the same time leads our eyes into an art historical mise en abyme.

Fig. 7: The Triumph of Photography in the Fototeca: Wagon 3, Florentine Festivals, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

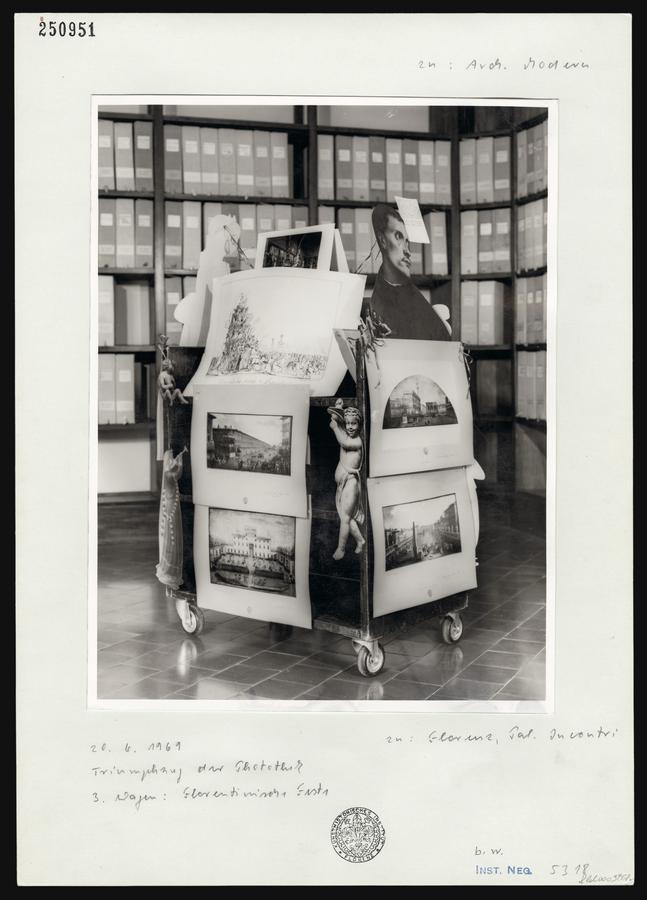

The final wagon (see Fig. 7) is dedicated to a profoundly Florentine theme, namely, the opulent early modern processions that took place in the city to mark secular and religious occasions and which the triumphal procession of photography looks back at as precursors. For the most part, views of sites in the city known for such celebrations are mounted on the carrello, particularly the Piazza Santa Croce, where the populace was provided entertainment in the form of horse races and tournaments as well as Calcio Fiorentino,5 an early form of football, and water sports. But the illustrations also include images from later periods such as the engraving from 1791 of a wild horse race at the city of Prato or the lithograph of a triumphal wagon of Jupiter that was constructed for a performance in Florence’s Teatro della Pergola on January 6, 1838.

Fig. hicollage7_1

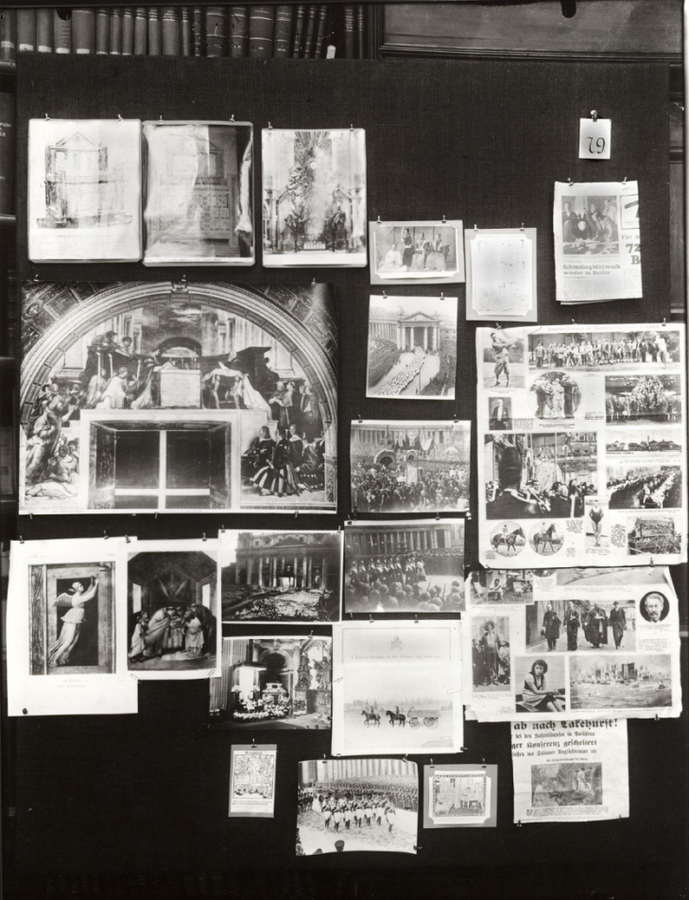

On the reverse (see the right wagon in Fig. 4) further sites of Florentine festivities, for example, a horse race on the Piazza Santa Maria Novella or a cavalcade on the Piazza della Signoria, are crowned by the self-portrait of Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun painted in 1790 during her Italian exile. The in part very detailed vedute with meticulous small staffage figures are counteracted on the edges of the carrello by large cut-out reproductions of cherubs and angels whose gestures seem to render homage to the procession of photographs on the final wagon. They not only function as a means of material cohesion between the mounted views of the city of Florence but also as an iconographic hinge between the representational levels of the processions in the illustrations and the June 1969 triumphal procession of photography in the Fototeca (see Fig. 8, compare in Hyperimage the fourth angel from left on upper row with the three front prints on right wagon in Fig. 4).

Fig. 8: Collezione Brogi in miniatura, Serie Fiorentina, Plate No. 35, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

This brief survey demonstrates how contingent the materials and pictorial contents of the triumphal procession of the Fototeca were despite the topics assigned to each of the wagons. In particular, large-format duplicates from the areas of Christian iconography and folkloristic genre pictures were selected that came from the old holdings of the commercial Brogi company, which were acquired for the Fototeca in 1966.6 In the process, photographs were used that were already far removed from their original pictorial context in Brogi’s compilation and then in part de-contextualized again by the actors of the Fototeca’s triumphal procession who cropped them.

It is precisely this heightened de-contextualization that allows the entirely new contingent arrangement of the photos on the carrelli. Historical details in iconic art now come into contact with folkloristic genre scenes, photographic reproductions of city views with kitschy (partly photographic) portraits of women, damaged prints with meticulously mounted, inscribed, and numbered photographs. Cropped angels, nuns, and artists encounter majesties, and museum galleries full of splendorous Renaissance sculptures find themselves situated right next door to a cluttered Rococo interior full of burlesque dancers. In short, the sole materially and visually stringent principle seems to be the juxtaposition of opposites—and that is a decidedly anti-archival principle.

However, another principle is effectuated in the photographs of the Florentine procession that is no less significant in the call for a playful ars combinatoria. I refer here to the picture-in-picture process that stimulates viewers to reflect on photographic mediality and materiality. The framing images make us aware of the object character of the photos within the pictures and vice versa.7 Consequently, the picture-in-picture interleavings undermine the coding of photographs as transparent evidential media and pure carriers of information for which they are often employed as archival source material. The indexical pointer of photography, its “there, that’s it” (Barthes 1984, 41), is transformed into a representation of precisely this deictic gesture (Sykora et al. 2016). In the case of the photographic interleavings, we are concerned with a medial mise en abyme that draws our attention to the reproductive character of the photos. On the other hand, the photographic layerings provide information on the different steps of their material handling as art historical source material, decorative objects for a festive performance, objects of archival classification or scholarly presentation. We synchronously see primary black-and-white pictures of artworks that were then used for the playful procession of photography, captured for the institute by a professional photographer. His photos were then mounted on cardboard, numbered, labeled, and classified by the head of the Fototeca at the time on July 17, 1969, cataloged in a database in 1993, and digitized in 2017. They were then shown to conference participants during my lecture on February 15, 2017, and are now available to readers of this publication.

Yet the photographs not only reference their object character through their complex framing but also demonstrate their materiality themselves. The surfaces and edges of many of the photographs are plainly visible. Scratches and incision marks where the figures are cropped clearly demonstrate the material limits of the pictures, making the limits of the photographic representations and the white reverse of the prints visible and giving a comment on the state of the photo’s material history and aging processes. It is precisely this damage to the photo objects and the spaces that open up between them that, however, tempt us to syntagmatically bypass the material and temporal gaps or mentally supplement the sections hidden by superimpositions. Such traces of non-archival handling open up for us the potential of a different way of dealing with the photos. It enables an epistemic practice that is particularly suited to discoveries: the optical unconscious identified by Walter Benjamin, that is, the unobserved details and surprising connections that unintentionally found their way into the photograph, are more easily visible in these kind of non-hermetic, broken up image arrangements and to a more vagabonding gaze rather than one that is burdened by codes and conventions.8

Fig. 9: Aby Warburg’s Picture Atlas Mnemosyne, 1927–1929, Plate 79, Warburg Institute Archive London.

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

Such an epistemic procedure strikingly resembles Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne picture atlas (see Fig. 9), the principle of which was also presented by the Hamburg scholar to an interested audience at the Florentine Institute on the occasion of a visit in October 1927. His presentation was based on a group of images of Medici festivities as depicted on the Valois Tapestries in the Uffizi (Mazzucco 2013). Following the founding of the KHI in the late nineteenth century, Warburg was one of those who not only favored the establishment of a library there but also a photo archive. As is well known, Warburg made use of his own image collection as a resource for representing the psychological influence of classical antiquity on the visualization of emotions in the Renaissance. Proceeding from this evolutionary perspective, he attempted to develop a general achronological cultural history of basic psychological formations, which, however, proved to be an unsolvable contradiction. But

while Warburg’s aspirations for an almost universal cultural theory culminated in an evolutionary history of the ‘formation and influence of expressive values’, the picture panels represent an autonomous experimental form in its own right based on the montage of the pictures on the panels, due to interpicturality (in conformity with intertextuality) and the possibilities for an endless reconfiguration of the respective constellations, through which the picture panels receive the character of an ars combinatoria. (Treml, Weigel, and Ladwig 2010, 614)

Warburg certainly also applied this to the picture collection at the KHI when he stated during his 1927 Florence lecture: “The Institute is not an instrument symbolising possession, but one epitomising musicality. Anyone who dares to may play on it.” (Warburg 1927–1928, 4) After 1924, he himself developed this combinatory approach into a method:

Not only did he continuously arrange and re-arrange the photographs on the screens, he also cut up the photographs of the screens, trying out new configurations on a separate sheet of paper. With both the photographs on and of the screens, Warburg continued to keep his argument in flux, constructing, de-constructing and re-constructing, but never bringing the project to a close. (Rumberg 2011, 249)

In the process, Warburg preferred the arrangement on vertical panels or hung screens to presentations that lay flat. The constantly rearranged pictorial configurations encompassing engravings, photographic reproductions of artworks, and clippings from illustrated magazines can be comprehended as a pictorial procedure (Rumberg 2011, 249) in which the images show themselves to the viewer like on a cinema screen and then withdraw again (Sierek 2007). The photographs that Warburg had made of the panels—like those on the Florentine cardboards showing the carrelli—not only served as an aide-mémoire and as a means of preserving an ephemeral pictorial arrangement but also an instruction to show the photos in the future again and again in different variations. This means that a repeated performance is inherent to both their materiality and configuration. Philippe-Alain Michaud’s statement about Warburg’s ways of dealing with his picture panels can therefore be transferred to the photos of the Florentine procession:

In this sense, it is based on a cinematic mode of thought, one that, by using figures, aims not at articulating meanings but as producing effects. […] The essence of the cinema resides not in images but in the relation among images, and the dynamic impulse, or movement, is born of this relationship. (Michaud 2004, 278, 282)

With reference to the triumphal procession of photos in the Fototeca, this indicates that their specific kinetic potential did not unfold solely during the brief occurrence that took place on June 20, 1969. Like their precursors, that is, the drawings and paintings depicting the early modern Florentine triumphal processions, their mediality of immobilization is instead turned into an agency of permanent performability. For although each

artistic fixation with its limitation to the visual appears deficient as opposed to the attractiveness of an ‘event’ that claims all the senses […] that which seems to mean a loss of authenticity is reversed into a triumph over the short-livedness of the factual performance. […] To the extent, namely, that the visualization of the triumphal intention releases the event from its ties to time and place, its effectiveness is optimised. […] The transportable triumph remains activatable wherever and whenever the need arises. (Kimpel 2001, 110)

7.3 Whimsical archons

This does not mean, however, that we can ignore the event and the actors of the plot in which the photos have a share. These actors in the procession are already present in the framing photos through the selection and montage of the photo objects on the carrelli. Moreover, a very special actor is the focus of attention in two of the photographs: Anchise Tempestini, the Fototeca’s research assistant, can be seen next to the three triumphal wagons, pointing in their direction with the gesture of a curator or street ballad singer (see Fig. 10 in Hyperimage). Through this demonstrative gesture of the archon, the deictic self-disclosure of the photo objects by means of their materiality and picture-in-picture interleaving attains a further quality: that of a theatrical staging.

In fact, Tempestini composed a long poem for the themes of each wagon in the rhythmic tradition of the canzoni accompanying the festive Florentine processions of the Renaissance, which he recited to the audience (see Fig. 11 in Hyperimage). The historical canzoni were intended to explain the meaning of the pictorial complexities on the wagons but, to outsiders, the performances remained “rather abstract, so that they had to use their imagination in order to interpret what they saw on the wagons” (Carew-Reid 1993, 110).9 This also applies to Tempestini’s poems, which were certainly more comprehensible for the procession visitors of June 1969 than they are for us. But his praise of Florence, of the KHI, and of photography were also understood as visual components of the procession and intended to last, which is illustrated by the fact that Tempestini wrote this praise by hand and attached his words between the photographs on the carrelli. Moreover, his texts were meticulously mounted on the back of the cardboards with the photos and placed in the same archive slipcase as the photographs, unfolding their witticism there not only thanks to their ingenious allusions but also because of the pseudo-seriousness of their archival preservation and presentation.

7.4 Conclusion

With the performance of the triumphal procession of photography, its photographic recording, and the whimsical reflection of archival procedure, the participants have not only considerably expanded their use of photography for in-house celebrations10 but also their professional handling of archival material. This effect can readily be transferred to our reception. If we, along with Gillian Rose and Elizabeth Edwards, posit that “the researcher is ‘produced’ by the agency of the photographs and of the archive” (Edwards 2011, 53), then the group of photographs from June 20, 1969 is not only a curious find that directs our attention retrospectively to an unruly practice in the center of the archive but also contains a forward-looking promise for us scholarly users of the Florentine photo archive: If we take the combinatory, material agency of the photos literally and take up their exceptional use through their archons during the 1969 triumphal procession, we can attain a form of freedom in our access to archives such as the Fototeca; in other words, when we twist and turn the photographic objects playfully until stray aspects flare up in a colorful kaleidoscope marked by material breaches, cuts, and scratches, a photographic autopoiesis may unfold that perhaps leads us in the direction of a “gayer science.”

7.5 List of Figures

• Fig. 1: Box with the photographs of the Triumph of Photography in the Fototeca, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, photo: Julia Bärnighausen, August 2017.

• Fig. 2: The Triumph of Photography in the Fototeca: Firenze com’era, 1969, unknown photographer, silver gelatin print, 18 x 24 (photo), 34 x 24 cm (cardboard), inv. no. 250945, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

• Fig. 3: Anchise Tempestini presenting the Triumph of Photography in the Fototeca: Firenze com’era, 1969, unknown photographer, silver gelatin print, 17 x 22.8 cm (photo), 34 x 24 cm (cardboard), inv. no. 250947, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

• Fig. 4: The Triumph of Photography in the Fototeca, 1969, unknown photographer, silver gelatin print, 17 x 22.6 cm (photo), 34 x 24 cm (cardboard), inv. no. 250949, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

• Fig. 5: The Triumph of Photography in the Fototeca: Wagon 1, Founding Time of the Fototeca, 1969, unknown photographer, silver gelatin print, 23 x 17 cm (photo), 34 x 24 cm (cardboard), inv. no. 250952, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

• Fig. 6: Mounted Photograph of the Triumph of Photography in the Fototeca: Wagon 2, Firenze com’era, 1969, unknown photographer, silver gelatin print, 23.9 x 18.1 cm (photo), 34 x 24 cm (cardboard), inv. no. 250952, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

• Fig. 7: Mounted Photograph of the Triumph of Photography in the Fototeca: Wagon 3, Florentine Festivals, 1969, unknown photographer, silver gelatin print, 23.9 x 18.1 cm (photo), 34 x 24 cm (cardboard), inv. no. 250951, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

• Fig. 8: Collezione Brogi in miniatura, serie fiorentina, plate no. 35, albumen print, 19.5 x 24.7 cm, inv. no. 616642, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

• Fig. 9: Aby Warburg. The Mnemosyne Atlas, October 1929: Mass. Devouring of God. Bolsena, Botticelli. Paganism in the Church. Miracle of the Bleeding Host. Transubstantiation. Italian Criminal Before the Last Rites, panel 79, Warburg Institute Archive, Warburg Institute London.

• Fig. 10 (in Hyperimage only): Mounted Photograph of Anchise Tempestini presenting the Triumph of Photography in the Fototeca, 1969, unknown photographer, silver gelatin print, 17 x 23 cm (photo), 34 x 24 cm (cardboard), size, inv. no. 250948, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

• Fig. 11 (in Hyperimage only): Mounted text handwritten by Anchise Tempestini, 1969, two sheets of 15.3 x 10.8 cm each, verso of inv. no. 250947, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut.

7.6 References

Agamben, Giorgio (2005). Profanierungen. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Barthes, Roland (1984). Camera Lucida. London: Fontana Paperbooks.

Bredekamp, Horst (2002). Florentiner Fußball. Die Renaissance der Spiele. Frankfurt a. M.

Caraffa, Costanza (2011). From Photo Libraries to Photo Archives: On the Epistemological Potential of Art-Historical Photo Collections. In: Photo Archives and the Photographic Memory of Art History. Ed. by Costanza Caraffa. Berlin and Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 11–44.

Carew-Reid, Nicole (1993). Les F êtes Florentines au temps de Lorenzo il Magnifico. Paris: Olschki.

Dercks, Ute (2013). Ulrich Middeldorf Prior to Emigration: The Photothek of the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz (1928-1935). Art Libraries Journal 28(4):29–36.

– (2014). ‘And because the use of the photographic device is impossible without a proper card catalogue’: The Typological-Stylistic Arrangement and the Subject Cross-Reference Index of the KHI’s Photothek (1897-1930s). Visual Resources: An International Journal of Documentation 30(3):181–200.

Edwards, Elizabeth (2011). Photographs: Material Form and the Dynamic Archive. In: Photo Archives and the Photographic Memory of Art History. Ed. by Costanza Caraffa. Berlin and Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 47–56.

Hubert, Hans (1997). Das kunsthistorische Institut in Florenz. Florence.

Kimpel, Harald (2001). Der Triumph im Kopf: Imaginäre Umzüge als Ansichtssachen. In: Triumphz üge: Paraden durch Raum und Zeit. Ed. by Harald Kimpel and Johanna Werckmeister. Marburg: Jonas Verlag, 110–127.

Levi-Strauss, Claude (1966). The Savage Mind. London: The University of Chicago Press.

Mazzucco, Katia (2013). Bild und Wort dans la conf érence d’Aby Warburg sur les tapisseries Valois: methode pour une Bildwissenschaft. url: https://journals.openedition.org/imagesrevues/2972 (visited on October 1, 2016).

Medina Lasansky, Diana (2004). The Renaissance Perfected: Architecture, Spectacle, and Tourism in Fascist Italy. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Michaud, Philippe-Alain (2004). Crossing the Frontiers: Mnemosyne Between Art History and Cinema. In: Aby Warburg and the Image in Motion. Ed. by Plippe-Alain Michaud. New York: Zone Books, 277–291.

Pollock, Griselda (2011). Aby Warburg and Mnemosyne: Photographic aide-mémoire, Optical Unconscious and Philosophy. In: Photo Archives and the Photographic Memory of Art History. Ed. by Costanza Caraffa. Berlin and Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 73–97.

Rumberg, Per (2011). Aby Warburg and the Anatomy of Art History. In: Photo Archives and the Photographic Memory of Art History. Ed. by Costanza Caraffa. Berlin and Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 241–252.

Sierek, Karl (2007). Foto, Kino und Computer: Aby Warburg als Medientheoretiker. Hamburg: Philo Fine Arts.

Stoichita, Victor I. (1997). The Self-Aware Image: An Insight Into Early Modern Meta-Painting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sykora, Katharina, Kristin Schrader, Dietmar Kohler, Natascha Pohlmann, and Daniel Bühler, eds. (2016). Valenzen fotografischen Zeigens. Kromsdorf and Weimar: Jonas Verlag.

Treml, Martin, Sigrid Weigel, and Perdita Ladwig, eds. (2010). Aby Warburg: Werke in einem Band. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Warburg, Aby (1927–1928). Untitled. Kunsthistorisches Institut Florenz: Jahresbericht 1927/28.

Footnotes

See information from Dr. Irene Hueck, e-mail correspondence, October 14, 2016.

See information from Dr. Irene Hueck, e-mail correspondence, October 14, 2016.

I employ the term “wild act” in reference to Claude Lévi-Strauss’s “savage mind” (Levi-Strauss 1966) and base my use of the word desacralization on Giorgio Agamben’s notion of profanization, insofar as the “holy,” which is suited as a vessel of collective cultural memory, is not destroyed in the process of desacralization but remains preserved as a strong reference (Agamben 2005).

The time frame of the founding phase of the KHI is not precisely delineated to the extent that preliminary stages of a semi-public collection can be traced back to an initiative of independent scholars in the late 1880s. The Verein zur Förderung des KHI Florenz was founded in 1898 and given a new charter and structure in 1903 that was based on mixed public and private financing and organizationally supported by a central and a local committee (Hubert 1997, 189). The establishment of a photo collection was planned from the outset: “the foundation consisted of circa 3000 photographs assembled by Herrmann Ulmann and made available in 1898 to the Institut following his death.” Translation from Hubert 1997, 125. See also Dercks 2013 and Dercks 2014.

Calcio fiorentino was played between 1530 und 1739. According to Bredekamp (2002, 9), however, it was part of the collective memory in Florence throughout the nineteenth century. In 1930, Calcio was “redesigned” under Mussolini. According to Medina Lasansky (2004, 64–69), in particular, the remodeling of the parade (corteo) was a fascist reinvention. I would like to thank Costanza Caraffa, head of the photo library at the KHI in Florence, for this information.

See information from Dr. Irene Hueck, e-mail correspondence, October 14, 2016, Caraffa 2011, 11–44, 21ff.

I borrow the terms “inset image” (Einsatzbild) and “framing image” (Umgebungsbild) from Stoichita (1997).

See Griselda Pollock’s thoughts on the optical unconscious—based on Walter Benjamin—as a paradoxical characteristic of photographs, i.e., the phenomena and their relationships that are unintentionally encompassed in the image and latently preserved there to later ostensibly offer themselves for decoding to the analytical eye of the viewer (Pollock 2011).

“Des chants et des poèmes étaient censés expliquer le sens des structures triomphales. Leurs textes étaient cependant écrits en fonction de valeurs et de notions souvent abstraites pour les non-initiés, qui devaient plutôt user de leur imagination pour interpréter ce qu’ils voyaeint sur les chars.”

Irene Hueck mentions that her predecessor, Dr. Eva Brües, had already invited the entire staff of the institute to the Fototeca in 1964 on the occasion of the stamping of the 200,000th photograph (see information from Dr. Irene Hueck, e-mail correspondence, October 14, 2016).