This paper considers the material dynamics on the edge of the archive. It argues that photographic practices form the ecosystem of the archive or museum, simultaneously maintaining, reproducing, and disturbing the hierarchies of value and categories that have created collections and performed photographs as certain kinds of things. However, these remain invisible practices, non-collections beyond the boundary of the archive, yet equally significant as epistemological and thus historical and cultural players.

Many years ago, working through the miscellaneous archaeological layers of the photograph collections at Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, I came across a brown envelope containing multiple resin-coated prints, probably dating from about 1960. The images were of historical photographs in the collection there. There seemed no rhyme or reason to them. The subject matter was very diverse but the groups of prints were all identical in and of themselves, the same number of prints for each image and they all had holes punched in their left-hand sides. The envelope carried some sort of caption, perhaps a date, and each photograph was just given a number (no description) which again I did not recognize as anything meaningful. Then it suddenly dawned on me. These were photographs that had been used as examination questions, these new material objects were the result of careful selection in the demonstration of some anthropological or ethnographic question or other.

Yet these photographs are material objects with an intended longevity of some sort, with a purpose, for an audience, within a disciplinary framework. Certainly, nobody had thrown them out. They told us something about that framework and something of the social activity of the image that they reproduced and projected across a dispersed plain of meaning. The photographs cannot simply be reduced to just “copies,” mere simulacra or duplicates, because they had a clear epistemological purpose in their own right. However, these photographs were there but not there, materially present, previously dynamic, yet intellectually invisible. They were outside the hierarchical structures that render some things preservable and others not. The fact that the brown envelope of photographs in the Pitt Rivers Museum cannot now be located, but I am sure is there, somewhere, rather reinforces the argument I wish to pursue here.

The experience of encountering these photographic prints sowed the seeds of a question which I have pondered ever since. How do we think about the material presence of photographs which are clearly active in the epistemological infrastructure of both a collection and its discipline, but are not recognized as of it in material terms? This paper is not about collecting policy or descriptive practices. There is a huge literature on these topics, and archivists and curators are trained rigorously in appraisal, acquisition, and disposal. Rather it represents some thoughts about the assumptions and hierarchies of value that shape the very existence of collections. Consequently, it is intended as a heuristic device to bring our categories of analysis to the surface.

The idea of analyzing collections and disciplinary infrastructures has become intellectually fashionable of late. It aligns with the increasing analytical emphasis on photographs, not as singular objects but as assemblages in social and institutional contexts, as sets of social relationships. But how is that assemblage of photographs constituted as a conceptual entity? Where is it located in institutional hierarchies? What are its boundaries? And what happens at those boundaries? Such questions are important because the current interest in the materiality, biography, multiple forms, and fluidity of the collection cannot be contained merely in the study of what has been institutionalized and managed as “the collection.” The collection is instead also located in the photographic actions around it, which continually activate that collection over a network of multiple performances that are materially present but institutionally invisible.

Before I develop this argument further, a few definitions are necessary. Rather than the term “archive,” I shall use “collection”—an assemblage of objects (including the digital) which encompasses here both museums and archives, although it should be noted that they have different agendas and the way they police their boundaries might be differently positioned in terms of material objects. But the processes that concern me are effectively identical over the territory. I also want to avoid “archive” in its more metaphorical usages that have been spawned by Derrida’s arguments in Archive Fever (Derrida 1996). While they resonate within my discussion, they are not my concern here.

3.1 Collections and non-collections

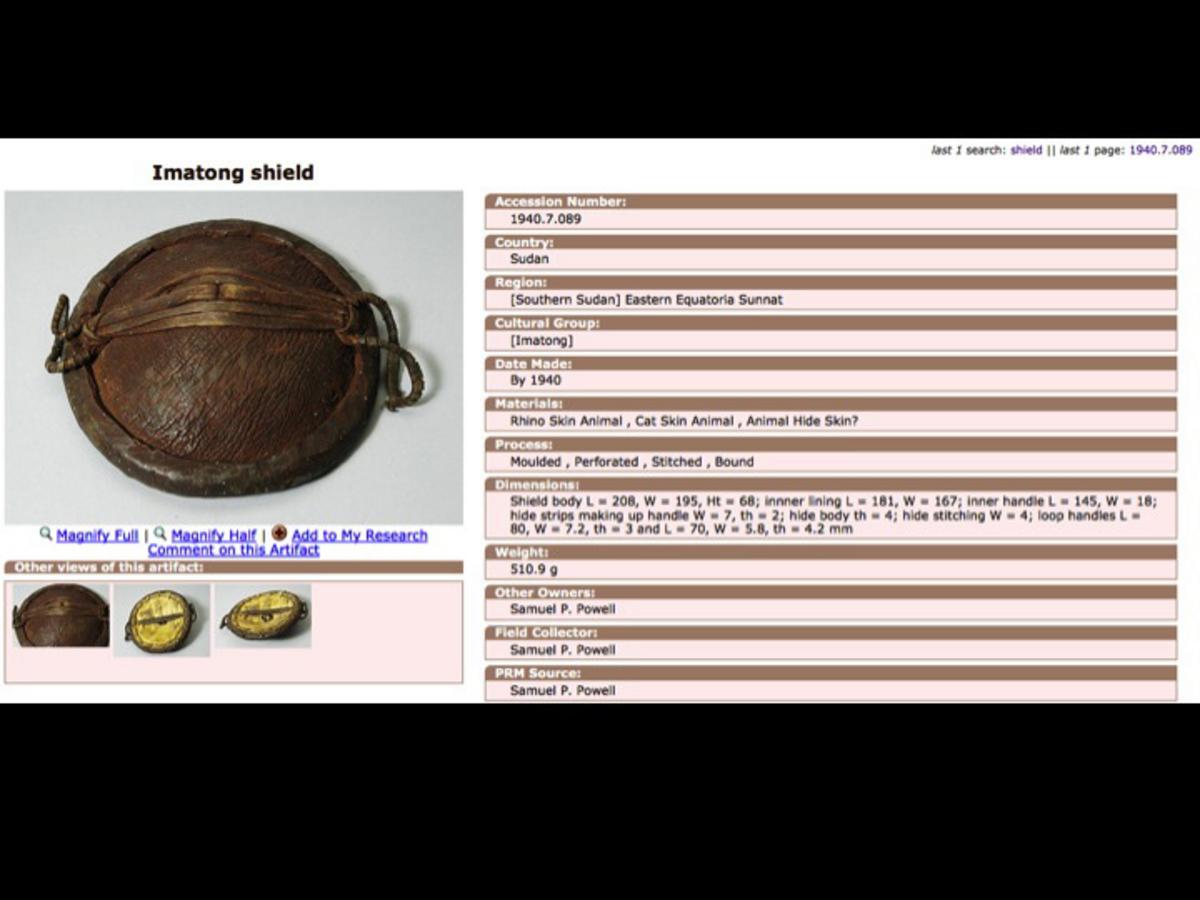

I am now going to consider the processes that designate photographs as “collections” or “non-collections.”1 Photographs are the only class of museum object that is simultaneously a collectable item (a significant object) and a tool of management (used to record and present objects within the museum from conservation reports to websites), whether we are considering the 1860s or contemporary uses. This is compounded by a slippage of language between “photograph” (a thing) and photography (a process or activity). These ambiguous and dichotomous relations are manifested through these “collections” and “non-collections.” That is, between, on the one hand, a sharply articulated material presence defined through institutional relevance, whether it be as art object or acknowledged collected items, for instance, in anthropology museums such as Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford or Musée du quai Branly in Paris (see Fig. 1). On the other hand is the non-collection—those myriads of historically located material photographic practices which exist in institutions but are not “collections.” If they are acknowledged, they often exist in a hierarchical relationship and are sequestrated to the margins of curatorial practice and kept, that is located, as “archives” or “related documents.” They are seen as servicing “real” collections, and understood as merely supporting, or providing information about, for instance, how ethnographic objects were worn, or the details of archaeological sites. Many more are sequestrated physically in service departments—photographic studios, design studios, and so forth—separated from the main business of “collecting.”

Fig. 1: Collections © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

However, these are vitally important photographs. In them resides the history of intersecting institutional and disciplinary epistemologies; they are what Lorraine Daston calls epistemic images (Daston 2015, 13–35). Yet they are not understood as such in their own right. This also translates into hierarchies of skill within institutions, with certain formative skills, such as photographic skills, being, again, invisible. This was neatly demonstrated in a conference question-time exchange with a senior keeper at a major German museum a few years ago. When I asked how the curatorial team planned the actual photography of objects for their impressive virtual gallery I was told dismissively: “We didn’t, that is a purely technical matter.” It seems that nobody had asked the intellectual question how do photographs change objects?

I have pondered the position I have just outlined for many years, as I watch institutions at work as user, curator, and commentator. Consequently, I shall now consider the implications of the material parameters of the collection and material and conceptual ambiguities at those boundaries as the material presence and practice of photographs in institutions are negotiated. I shall tackle this from three perspectives which overlap and mutually inform one another. First is the concept of ecosystem which, drawing on ideas of network or meshwork, has been applied increasingly to institutional processes and practices. Second are what I am calling “thought-landscapes” and maintenance of institutional categories. These are constituted through what might be described as “second-order epistemologies” perhaps, characterized by a dense genealogy of assumptions. These assumptions police the boundaries and purify the collections and the value systems that sustain them (Edwards 2017). I am especially concerned with the differential visibility which determines the categories and hierarchies of value. Thirdly, and finally, I shall look at agitation at the boundaries—because boundaries are transformative spaces where both dangerous and productive things can happen.

Underlying my argument are two key papers which offer useful ways to think about the questions I have outlined. First is Marilyn Strathern’s 1996 essay “Cutting the Network” (Strathern 1996, 517–535) in which she discusses the relationship between the concept of the hybrid and the network. If a network is a socially expanded hybrid, then hybrids are condensed networks—and what are the conditions of its stasis or stabilization? Where does obligation within a network end? This concept works well in determining the complex relations between collections and non-collections. Second, I draw on Christopher Pinney’s 2005 essay “Things Happen” (Pinney 2005, 256–272) which asks from what moment we can say an object comes and to what extent the presences and work of things, here photographs, emerge from multiple realms and moments that are manifested through multiple and temporally dispersed material forms and that confront historical and cultural assumptions and categories.

Fig. 2: Non-Collections. Management Photographs © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Behind this are, of course, much wider questions which are beyond the scope of this essay and which in any case have been well chewed over. How institutions make objects one kind of thing or another? How epistemologies translate into location and into category and to what extent categories might be sustained or challenged over time? It is now a museological commonplace that institutions create certain ways of seeing that make, translate, and consolidate objects as certain kinds of things—“the museum effect.” As art historian Svetlana Alpers stated, “everything in a museum [here my collection] is put under the pressure of a way of seeing” (Alpers 1991, 29).2 This establishes the parameters of interest and quality of attention given because institutions are, as Gillian Rose has noted, “groups of statements which structure the way a thing is thought” (Rose 2001, 136). Photographs thus become disciplinary roadways that, as Mary Morgan has put it, “facilitate the travelling of facts, but at the same time, like rails, they may also limit the range and possibilities for travel” (Morgan 2011, 31). However, for all this scholarship on the categories of and practices related to collections, remarkably little attention has been given to photographs despite, or perhaps because of, their ubiquity. Yet photographs present us with perhaps the most perplexing kind of object, being, with equal epistemological force and symbiotic power, both collections and “non-collections.”

3.2 Ecosystem

Fig. 3: The Shop: National Gallery, London, photo: Elizabeth Edwards.

I turn first to the idea of collection/non-collection as an ecosystem. An ecosystem might be defined as a barely perceptible yet palpably present network of finely balanced, yet vital, sets of interconnections, dependencies, benefits, and threats. It sustains a particular environment expressed through practices, materialities, hierarchies, and values (Edwards and Lien 2014, 4–5). The various manifestations of photographs in institutions are such an ecosystem. As I have already noted, photographic manifestations do not simply stop at the discrete material object but they spawn a mass of material objects that make meaning around the discrete object (see Fig. 2). There are accession photographs, conservation photographs, loan and condition report photographs, research photographs and all are historically located. There is an extent to which the museum object becomes a sum of its parts (which we must remember includes photographs). Photographs in the institutional ecosystem also exist, in material forms, as multiple originals: negatives, prints, digital scans, lantern slides, 35mm transparencies, publication prints—copies of copies, copies of copies of copies, a vast network of dependencies. As Malraux commented, photography became the organizing device which establishes the vast heterogeneity of the collection to a single perfect similitude3 (see Fig. 3). The apotheosis is perhaps the museum shop, where all objects are reduced to a series of consumable photographs, gathered around the collection, and spread across innumerable forms.

Thus, the photographic ecosystem is arguably the expanded instrument through which things, objects, can show themselves. Photographs mediate both existence and experience—consequently, the role of the ecosystem is “not simply instrumental but hermeneutic,” defining thought-landscapes, as materialities create their own force fields in a mesh of possibilities (Domanska 2006, 172; Pinney 2005, 261).

Despite the network of dependencies that feeds and stabilizes the values of museums and archives, these are made up of intersecting epistemologies that cluster around “the object” in different ways. They may “look” the same in representational terms, carrying a seductive visual equivalence that elides the work of material nuance. In many instances, non-collections of photographs look very like “collection” photographs themselves, merely with a different material form—traces of traces of traces. But, at the same time, there are historical layers to the representational practices around photographs themselves within the institutional ecosystem. These are significant because they track shifts in evaluation and the making of meaning. For instance, at the V&A, the first postcards, or non-collection photographs, produced for sale from photographs in the “collections,” were produced (and apparently sold, for they are reprinted) as hard, high contrast, glossy black and white prints, with no sense of the material qualities of the object.4 Meanings are dispersed through multiple material performances. The assumption is that these photographs are series of disaggregated forms that can be rendered collections or non-collections. However, all material players in the ecosystem are subject to the careful negotiated balance of meaning and practice. I would argue that we are looking at a dispersed flow of related objects that make meanings within a common discourse and ecosystem, some of which are deemed ephemeral, while some are preserved. Yet all carry forms of agency, effect, performativity, and power.

Perhaps they can be characterized as what anthropologist Alfred Gell has described as a “distributed object,” in that there is a surface coherence—here, that of photography—but is comprised of multiple objects with different microhistories and subject to different forms of evaluation over space and time (Gell 1998, 221). Of course, the different strands of practice forming these microhistories constitute the ecosystem. As I have noted, those processes are often invisible—as is much of an ecosystem—below the metaphorical waterline. But these repetitions constitute hybrids of complex epistemologies and value systems at the intersection of different knowledge systems which sustain institutions.

3.3 Categories

I shall now turn to the way in which ecosystems translate into categories of action and process, as photographs are controlled by the imposition of patterns of saliency and visibility. How do institutional thought-landscapes manifest themselves as categories and hierarchies of value which translate and fragment the ecosystem into collections and non-collections? All history is texted by the pattern of its archiving; of course, it was ever thus. But given the expanded base of photographic study, where does this leave us in the potential infinity of the network? Strathern’s concept of “cutting the network,” the perceived limits of relational action, can be used to account for the way in which some sets of ecosystem relationships are deemed no longer valid or even desirable. Yet if we are to write our institutional ethnographies, our histories of material practice, our biographies of objects, this ecosystem is central—the relations between collections and non-collections have historiographical impact. Consequently, one must ask: what are the actions of such categories?

Categories are, as Michel Foucault has famously argued, an epistemological apparatus that constitute political, social, and moral discourses. Categories allow a thing, here a photograph, “to pass over in its entirety into the discourse that receives it” (Foucault 1970, 135). Categories have ideological origins, and their consequences become naturalized within institutional practices and agendas and resonate through them long after their apparent demise. This is again familiar analytical territory, but it is worth restating.

Perhaps the root of photographs’ uncertainty in institutions is their ambiguity in the key areas of disciplinary-value hierarchy—uniqueness, preciousness, significance, and material specificity. Photographs, as we have noted, exist as multiple originals. With the exception of daguerreotypes, tintypes, polaroids, and a few other single-image technologies, this multiplicity is a defining characterization of the medium. Consequently, a range of museums can hold historical and contemporaneous prints of a photograph by, for instance, Talbot, or Alinari, and still legitimately claim to hold an “original.” As I have noted, however, photographs spawn further originals, which also reside in institutions, for instance, negatives, multiple prints, lantern slides, copy and mediated prints (details, crops, enlargements), and even the born-digital. All have legitimate claims to be “original historical objects.” Thus, as I noted earlier, the very physical identity is ambiguous in institutional terms as the “originality” and “significance” of “a photograph” might be dispersed across many related but discrete objects. As Pinney has asked, “from what moment does this object come?” (Pinney 2005). Good question. The ubiquity of forms challenges the hierarchies of value and the categories that sustain them. What is a multiple original, what is a reproduction, and when does it become historically significant? Categories shape the conditions under which the ecosystem becomes visible.

Different kinds of institutions have, of course, different sets of boundaries between “collections” and “non-collections.” “Archives” are more inclusive conceptually and materially than “art galleries,” for instance, and within this, objects are subjected to different levels of intellectual control. But there is nonetheless a general pattern to non-collections. They exist in a hierarchical relationship with other classes of objects and are often sequestrated to the margins of curatorial practice and kept, that is, located, as “archives,” that is, outside the value systems of “collections.” And there are categories within non-collections, those that are recognized as having historical significance and are now subject to considerable historical analysis. For example, most anthropology archives now come into this category and are recognized as being “collections” even if this remains contested in some quarters. Yet the presence of photographs is perhaps not seen as dynamic within institutions. Once, in conversation with a social history curator who I knew had 35,000 glass plates of local interest in his collection, I asked how he thought about the photographs in relation to the rest of the collection. His answer was, “Well we don’t really, they are just there.”

Fig. 4: Non-Collections, photo: Elizabeth Edwards.

However, equally important are the massive photographic non-collections (see Fig. 4), as I have suggested, scattered through institutions, that cluster around institutional practice and track concepts of significance within the institution—that vast heterogeneity that André Malraux noted (Malraux 1965). The history of institutions is vested in their non-collections, which are often unlisted, cataloged—just there, but represent an enormous force of epistemological performance. They are nonetheless subject to categories that perform a form of purification on which institutional identities, and indeed integrity, depends. Consequently, most non-collections are marked by their intellectual invisibility.

These categories are played out in everyday institutional practices. For instance, the dominant form of photographic collecting for “art collections” has been the print. This relates to the discourses of modernist curatorship and the fine print, the final act of photographic production. Conversely, negatives are not perceived as having aesthetic value in and of themselves. Thus, negatives, like other “functional” forms such as lantern slides, tend to be marginalized as archives, as supporting objects of higher hierarchical value. For instance, Damarice Amao has described the practical and conceptual challenges to the core assumptions of photographic collecting practices when the photographic work of surrealist artist Eli Lotar was acquired by the Georges Pompidou Centre not as prints but as unremarkable boxes of negatives (Amao 2015, 231–245).5 Glenn Willumson, writing in 2004, argued that stereocards had been largely excluded from writing on “the history of photography” because not only were they “commercial” and mass-produced but their small, questionable print quality made them “unexhibitable” in terms of gallery aesthetics (Willumson 2004, 84–99). This situation has only changed with more widely available digital display technologies (see Fig. 5), more “cultural history” and material approaches to photography, which have brought stereocards into a more active institutional dynamic, for instance, at the Tate Britain’s 2014 exhibition, The Poor Man’s Picture Gallery.6 I shall return to the question about how things change category later.

Fig. 5: Cultural Histories as Collection Tate Britain, photo: Elizabeth Edwards.

The flow of photographs across categories in their multiple and hybrid forms within the ecosystem has to be managed to maintain the boundaries between collections and non-collections, to establish the purity of the photographic. As Douglas Crimp notes, the “fatal error” for museums, especially those invested in photography, is to admit the very thing that constitutes it (Crimp 1993, 56).

3.4 Blurred boundaries

Finally, I turn to the boundaries which have been too much assumed through my account. It is very easy to reify boundaries, and institutions have a tendency towards a rhetorical reinforcement of the boundaries, so that they can then claim to push against them when the need for some excitement is felt, for instance, the fascination of the art world with what they term “vernacular” photographs.

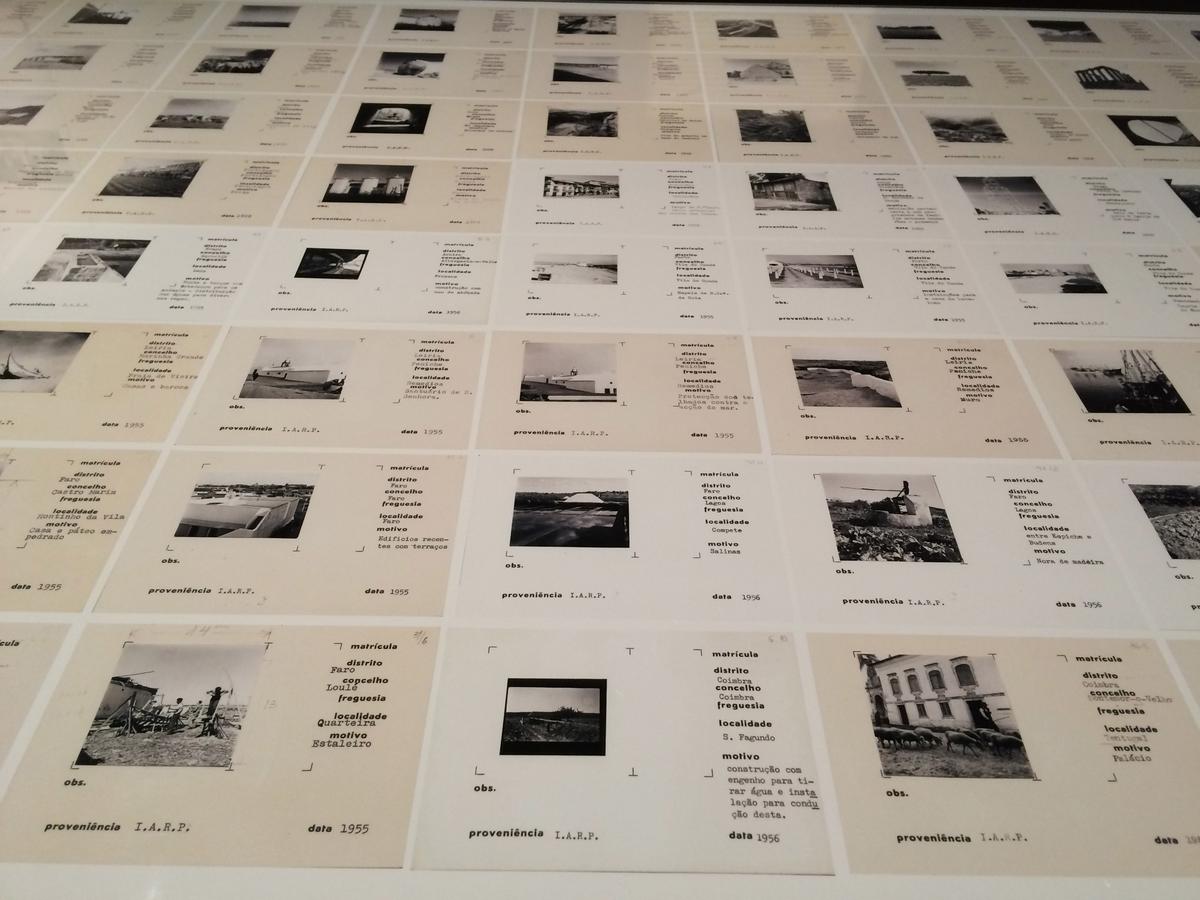

As we have seen, institutional categories intervene in the network of photographic flows and dictate what are collections and what are non-collections. As anthropologist Patricia Spyer has argued, in a way that resonates with my collections/non-collections model, things at boundaries are neither “here” nor “there,” neither fully absent nor unambiguously present (Spyer 1998, 1). Are non-collections invisible or merely unacknowledged objects of terror at the boundary of the unknown? Network as a concept has done much to blur categories, giving off as it does “diverse signals” (Strathern 1996, 520). Tim Ingold’s concept of meshwork is perhaps even more productive, in that relations constitute an interwoven tissue of knots rather than being simply connected (Ingold 2011, 70). What are the categories at work as the borders between collection and non-collection are re-negotiated? For such renegotiations are becoming increasingly frequent as the social, cultural, and material history of photography that I have noted becomes more visible. For instance, the recent exhibition in Lisbon which explored the folkloric survey in mid-twentieth century Portugal through its material/visual archival deposits (see Fig. 6).7

Fig. 6: National Museum of Ethnology, Lisbon, photo: Elizabeth Edwards.

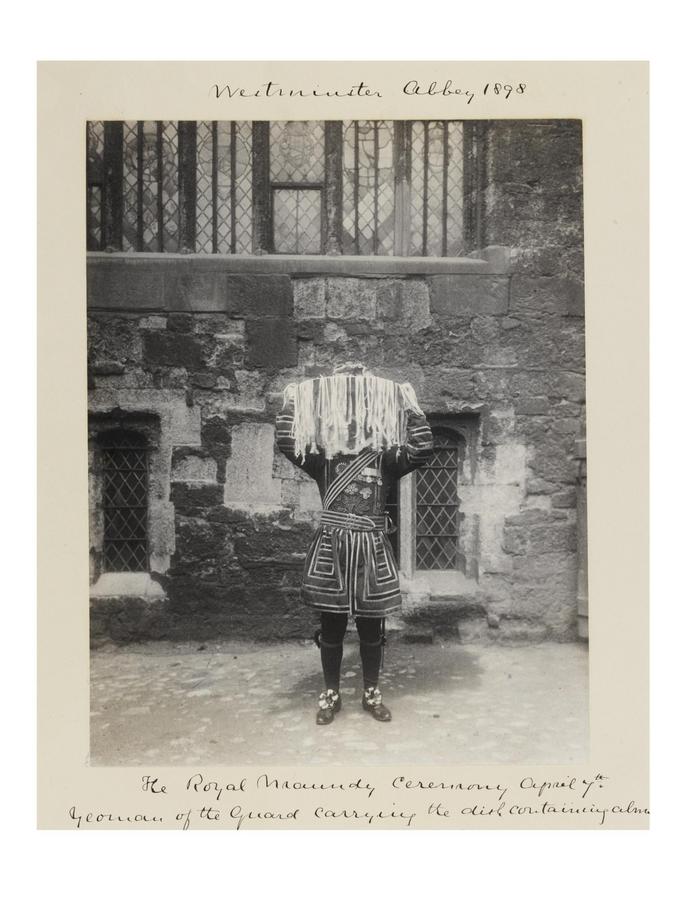

However, while there is this increasing engagement with non-collections, we also have to ask about the terms of that engagement. While there is much important anthropological and sociological work at the edges of the collection engaging precisely with that ambiguity, such as the excellent exhibition in Lisbon, in many cases, I would argue that non-collections are being absorbed, not in terms of expanded categories of analysis, but rather into existing categories of evaluation and analysis. For instance, it is interesting to watch the trajectory of Sir Benjamin Stone’s “record photographs” (see Fig. 7). He is transformed from the rather dull photographer he was through the privileging of single images that appeal to presentist categories, as he becomes, for instance, a proto-surrealist. Of course, objects are constantly reinterpreted, but what is interesting here is that the absorption of non-collections is dependent on their perceived ability to speak to and reinforce extent categories of value rather than disturb those categories.

Fig. 7: Maundy Money, 1898, Sir Benjamin Stone © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Another instance here is the increasing visibility of the V&A Guard Books. The Victoria and Albert Museum (or South Kensington Museum as it was until 1899) was the first UK museum to make photography integral to its museum practice and management, photographing many of the objects in its care from the late 1850s onwards. These photographs were placed in Guard Books, which could be consulted as needed, and indeed prints were sold to the interested public,8 with a second set used as student reference prints in the Library. But they were not “collections,” indeed the idea of collecting photographs as museum objects, beyond a documenting and recording function, was barely recognized until about 1900 (Haworth-Booth and McCauley 1998, 30). So those photographs became “non-collections,” subject to different management practices from “collections.” They were identified only at file level and, spatially separated, kept not in the “collections” but in the Library and then the archive. While increasing interest in the history of the institution has renewed interest in these archival objects, their uneven absorption into the narratives of “the collection” has been interesting. Prints extricated from the Library set, framed on the gallery wall, and privileging the photographer as “artist,” they are translated into precious objects.9 Their significance lies not in their institutional dynamics but in their alignment with established categories of “fine early photography.”

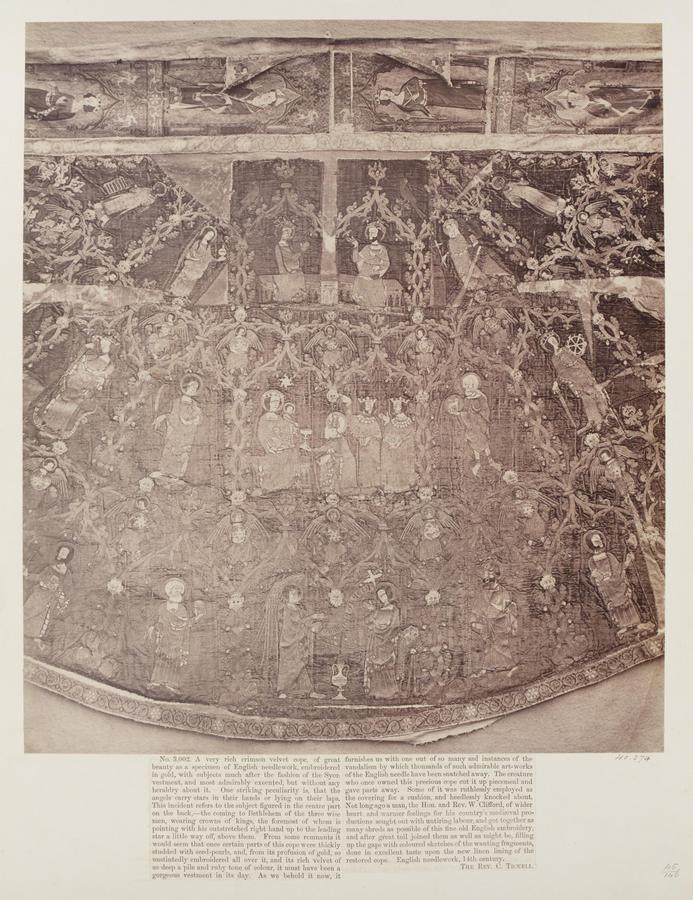

Fig. 8: The Butler Bowden Cope, 1862, Thurston Thompson © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

We can actually observe these agitated boundaries in action. A photograph of the early fourteenth-century Butler-Bowden cope (see Fig. 8) was taken in 1862 by Charles Thurston Thompson who was at the time the South Kensington Museum’s chief photographer. It is a curatorial management record for a loan exhibition: “Specimens Selected from the Special Exhibition of Works on Loan at the South Kensington Museum in 1862.” Yet such is the embeddedness in the ecosystem that the V&A reproduces the photograph in its catalog for its 2016 exhibition Opus Anglicanum on medieval English embroidery, with little sense of time or historicity or the material force field of the photograph as a material object. Indeed, the 1862 text appended to the archival object has been cropped out in the catalog (Browne et al. 2016, 109–10). Arguably, this photograph has become what Pinney has described as “uncontemporaneous,” operating in a network of multiplicity that functions as both similar and different.

The photograph is on the move, however. If one consulted the online catalog for this photograph early in 2017, the photograph was historically positioned as non-collection. The text read:

Photographs such as these were originally collected by the National Art Library as part of a program to record works of art, architecture and design in the interest of public education, these photographs were valued as records and as source material for students of architecture and design.10

Then we got the blurring of the categories and the movement from non-collection to collection. It continued:

As well as being crucial records of the history of the V&A, and an important element within the National Art Library’s visual encyclopedia, these photographs are also significant artefacts in the history of the art of photography.

However, in February 2017, this description suddenly changed and the photograph of the cope became positioned in terms of the history of institutional practices, which simultaneously obliterated the history of the evaluation and interpretation of this photograph.11 The categories shift almost before our eyes.

Thus, there is a marked tendency for previous “non-collections” to become “collections” because they accord with the dominant discourse of rare early photography or as prehistories of dominant, and indeed, marketable aesthetic. They shift from “use value” to “age value” to employ Rieglian categories (Riegl 1982, 21–51). The network reaches a moment of stasis as institutional hierarchies of value, informed by “age value,” intervene and these ambiguous objects are stabilized within this rhetoric. It is this, not their institutional history, which enabled them to shift category. Arguably, following Pinney, these are “wavy meanings—open to recoding but not anchored to a specific historical moment” (Pinney 2005, 267), but rather to moments of transubstantiation through shifts in nomenclature: from non-collection to collection, from archive to object. But, in this case, there are readings that lack this openness of the object to true transubstantiation into a different kind of thing, to quote “a further unfolding of the complex identity of the central object” (Pinney 2005, 267).

In this paper, I am not suggesting that, as we look at the longevity of something made by deep levels of the ecosystem, any of this is necessarily wrong in bald terms—things happen and things happen to images—it was ever thus. Photographs have always been hostages to their reproducibility and hybrid forms; it is the root of their ambiguity within the institutional ecosystem, and, I suspect, the root of our intellectual fascination with them. But why this is interesting is that it demonstrates the temporal and category complexities of the ecosystem and how the flow of photographs works over multiple perspectives, “uncontemporaneous” flows which are brought into momentary alignment through institutional practice and the categories that sustain it.

Yet as we extend the range of what it is to write photographically centered histories, anthropologies, or sociologies, these questions of institutionalization become more pressing. Because it sometimes appears that institutional practices and historiographical dynamics are moving in different directions or at least pushing on different boundaries or frames. Further, one suspects that as digital asset management takes hold in museums and archives, this will merely reinforce traditional boundaries between “real objects” and their multiple and assorted surrogates as the networks are cut more closely to traditional categories of value. And this represents a major point of danger for material collections. Where do we place the limits on technologies and ideas which “promise to run away with all the old categorical divisions” (Strathern 1996, 519)? At what point does the network cut or stabilize? And to what ends? What will be the price to pay in how we write photographic histories? Because we all know what happens when one starts messing with ecosystems.

3.5 Some closing thoughts

This paper has scratched the surface of some big questions, but ones which resonated through the conference as papers addressed, in some way, the ambiguous formations of the ecosystem. To really grasp how the ecosystem of photographs and photographic practices work in institutions, especially at the putative boundaries of the archive, it may be more appropriate to consider photographs as “densely compressed performances unfolding in unpredictable ways.” It is this that makes them resistant to any particular moment. The energy with which the boundaries of institutions are maintained to counter such insurrection by non-collections rather suggests this to be the case (Pinney 2005, 266–269).

Studies that put photographs (whether analog or digital) at the heart of their analysis of epistemological regimes require a sensitivity to the complete ecosystem of images and practices, a network of multiple material forms and performance of images which make things, including other photographs, what they are. This is not merely a celebration of the margins of categories but an excoriation of boundaries and categories (Strathern 1996, 520) and a study of the tension between pure and hybrid forms which are part of the different epistemological claims. If we think of photographs not simply as material objects but as meshworks of hybrid forms that can accommodate multiple claims upon them and act as a critique of separations, here between collections and non-collections, there is the potential for a refigured understanding of the institutional practices that embed photographs in archives and museums.

The fact remains, however, that the practices of institutional evaluation shape the patterns of historical endeavor. So where do obligations to material forms (including the digital) stop? What is gained and what is lost in shifts in the ecosystem? The historiographical turn that takes photographic studies to multiple and entangled sites of analysis cannot be contained within the material singularity of the image and the archival systems that gave support to it. Instead, it is research which enters the ephemeral spaces of non-collections, which can all too easily become methodological quicksand.

The question is not whether these things happen or not, whether there are collections and non-collections, or even whether it is a good or a bad thing. Rather, it is a question about the modality of the relationship: what is its resonance? What is the media archaeology of institutions and their collections through which epistemic effects are realized and revealed? How do we accommodate what Pinney has called “the alien and haunting presence of things that we have made but might, in their institutional presences, also produce disjunction and incoherence” (Pinney 2005, 256)? Simultaneously, we need to be aware of the submerged institutional categories and the dense genealogies of assumption which, despite our best efforts, continue to intervene in the network of value, creating a stasis in their own image, within the hybrid flows of collections and non-collections.

3.6 List of Figures

• Fig. 1: Collections © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

• Fig. 2: The Shop: National Gallery, London, photo: Elizabeth Edwards.

• Fig. 3: Non-Collections. Management photographs © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

• Fig. 4: Non-Collections, photo: Elizabeth Edwards.

• Fig. 5: Cultural Histories as Collection: Tate Britain, London, photo: Elizabeth Edwards.

• Fig. 6: National Museum of Ethnology, Lisbon, photo: Elizabeth Edwards.

• Fig. 7: Maundy Money, 1898, Sir Benjamin Stone © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

• Fig. 8: The Butler Bowden Cope, 1862, Thurston Thompson © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

3.7 References

Alpers, Svetlana (1991). The Museum as a Way of Seeing. In: Exhibiting Cultures. The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. Ed. by Ivan Karp and Steven Lavine. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Amao, Damarice (2015). To Collect and Preserve Negatives: The Eli Lotar Collection at the Centre George Pompidou. In: Photographs, Museums, Collections: Between Art and Information. Ed. by Elizabeth Edwards and Christopher Morton. London: Bloomsbury, 231–245.

Browne, Clare, Glyn Davies, M. A. Michael, and Michaela Zöschg (2016). English Medieval Embroidery: Opus Anglicanum. New Haven / London: Yale University Press/V&A.

Crane, Susan A. (2013). The Pictures in the Background: History, Memory and Photography in the Museum. In: Memory and History: Understanding Memory as Source and Subject. Ed. by Joan Tumblety. London: Routledge, 123–140.

Crimp, Douglas (1993). On the Museum’s Ruins. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press.

Daston, Lorraine (2015). Epistemic Images. In: Vision and Its Instruments: Art, Science, and Technology in Early Modern Europe. Ed. by Alina Payne. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 13–35.

Derrida, Jacques (1996). Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Domanska, Ewa (2006). The Return to Things. Archaeologia Polana 44:171–185.

Edwards, Elizabeth (2017). Location, Location: A Polemic of Photographs and Institutional Practices. Science Museum Group Journal 7 (Spring 2017). doi: 10.15180/170709. url: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170709 (visited on August 17, 2019).

Edwards, Elizabeth and Sigrid Lien, eds. (2014). Uncertain Images: Museums and the Work of Photographs. Farnham: Ashgate.

Edwards, Elizabeth and Christopher Morton, eds. (2015). Photographs, Museums, Collections: Between Art and Information. London: Bloomsbury.

Faria, Nuno (2016). Inqu éritos ao Território: Paisagem e Povoamento. Roteiro. Lisbon: Museu Nacional de Etnologia.

Foucault, Michel (1970). The Order of Things. London: Routledge.

Gell, Alfred (1998). Art and Agency. An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hamber, Anthony J. (1996). “A Higher Branch of the Art”: Photographing the Fine Arts in England, 1839-1880. Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach.

Haworth-Booth, Mark and Anne McCauley (1998). The Museum and the Photograph: Collecting Photography at the Victoria and Albert Museum 1853-1900. Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.

Hooper-Greenhill, Eilean (1992). Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge. London: Routledge.

Ingold, Tim (2011). Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kratz, Corinne A. (2011). Rhetorics of Value: Constituting Worth and Meaning through Display. Visual Anthropology Review 27(1):21–48.

Malraux, André (1965). Le Mus ée imaginaire: les voix du silence. Paris: Gallimard.

Morgan, Mary S. (2011). Travelling Facts. In: How Well Do Facts Travel? The Dissemination of Reliable Knowledge. Ed. by Peter Howlett and Mary S. Morgan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pinney, Christopher (2005). Things Happen: Or, From Which Moment Does That Object Come? In: Materiality. Ed. by Daniel Miller. Durham NC: Duke University Press, 256–272.

Riegl, Alois (1982). The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin. Oppositions 25 (Fall 1982):21–51.

Rose, Gillian (2001). Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials. London: Sage.

Spyer, Patricia, ed. (1998). Border Fetishisms: Material Objects in Unstable Spaces. New York and London: Routledge.

Strathern, Marilyn (1996). Cutting the Network. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 2(3):517–535.

Willumson, Glenn (2004). Making Meaning: Displaced Materiality in the Library and Art Museum. In: Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images. Ed. by Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart. London: Routledge, 84–99.

Footnotes

There is an emerging literature in this field which moves beyond the consideration of “art” collections to analyze the entanglement of photographs within museums in particular. See Hamber (1996) and more recently Kratz (2011, 21–48); Crane (2013, 123–140); Edwards and Lien (2014); Edwards and Morton (2015b) as well as essays therein. See also https://www.fotomuseum.ch/en/explore/still-searching/authors/29334_elizabeth_edwards, accessed November 21, 2017.

See also Hooper-Greenhill 1992.

Quoted in Crimp 1993, 54.

V&A Archives A0803. Significantly great care appears to have been taken with the material qualities of other classes of museum object.

Significantly, in 2017, Eli Lotar was the subject of a major exhibition at the Jeu de Paume, Paris, http://www.jeudepaume.org/index2014.php?page=article&idArt=2719, accessed July 19, 2017.

Carol Jacobi: “Tate Painting and the Art of Stereoscopic Photography,” https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/display/bp-spotlight-poor-mans-picture-gallery-victorian-art-and-stereoscopic/essay, accessed November 21, 2017.

See Faria 2016, see also https://mnetnologia.wordpress.com/edicoes-online/, accessed July 19, 2017.

The series of some 900 volumes is at V&A Archives MA/32. The Guard Books are currently being digitized and integrated into institutional histories. I am grateful to Steve Woodhouse for discussing this project with me.

See the 2016/17 exhibition The Camera Exposed, https://www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/the-camera-exposed, accessed July 19, 2017.

This text cannot be verified except in the author’s transcription because it has been removed from the website.

See http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1280324/cast-of-portico-de-la-photograph-cowper-isabel-agnes/, accessed November 21, 2017.