1.1 FA-Perg34-0002

The archive of the Antikensammlung (Museum of Classical Antiquities), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, holds a large collection of photographs relating to the archaeological excavations conducted by this and other institutions since the 1870s. Here we find a photograph that is worth examining in some detail (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Upper body of a colossal double statue from the Red Hall in Pergamon, unidentified photographer, 1900, albumen print on cardboard mount, 16.8 x 23 cm (photo), 25.2 x 33.4 cm (cardboard), Antikensammlung, SMB, inv. no. FA-Perg34-0002.

It is an albumen print (16.8 x 23 cm), evidently derived from two negatives placed side by side, in other words, two separate photographs, printed together, that show the same archaeological find, apparently the torso of a colossal double-sided statue, viewed from two different angles. The albumen print is mounted on cardboard (25.2 x 33.4 cm), originally blue, but now much yellowed by age; like a palimpsest, it is liberally covered with inscriptions, stamps, annotations, and numbers, some superimposed, in different scripts, media, and colors.

One of the stamps, “Pergamon,” above the photograph to the right, enables us to connect this object with the excavations conducted, in successive campaigns, by German archaeologists in this ancient Greek city in Asia Minor, now Turkey, then the Ottoman Empire; and the inscription “Perg. 1900” to the left evidently refers to the place and date of the photograph. The photograph is in the archive of the Antikensammlung, but the circular stamp in the center of the card mount to the right is from the Kaiserlich Deutsches Archaeologisches Institut Central-Direction Berlin (head office of the Imperial German Archaeological Institute in Berlin). Both the support and the photograph bear numerous signs of wear and tear, and the bottom right-hand corner of the mount is torn off.

Let us take the cardboard in our hands and observe the photograph in close-up, perhaps moving it back and forth under a raking light. On the left-hand side, above the archaeological find, there is a whitish stain on the photographic print, now turned grey by the passage of time, evidently resulting from a retouch to the positive. On the right-hand half of the photograph, immediately above the marble torso, the darkened stain of a similar retouch has partially flaked off, allowing the image of the bust of a child to resurface. The bust in question, however, is not part of the sculpture, but that of a real-life child who seems to be emerging from inside the torso. If we look again more closely at the image on the left, we will glimpse, underneath the retouch, the head and pigtail of the same child.

Among the various annotations on the mount, close to the top left-hand corner, is a pencil inscription “FA-Perg34-0002.” This number identifies the photograph and will be used below as a shorthand name for the image in question; it was added to the mount in 2016 by our colleagues Petra Wodtke and Victoria Kant at the Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, in the context of the collaborative project “Photo-Objects. Photographs as (Research) Objects in Archaeology, Ethnology and Art History,” of which the present publication is a spin-off. We will return to this project below.

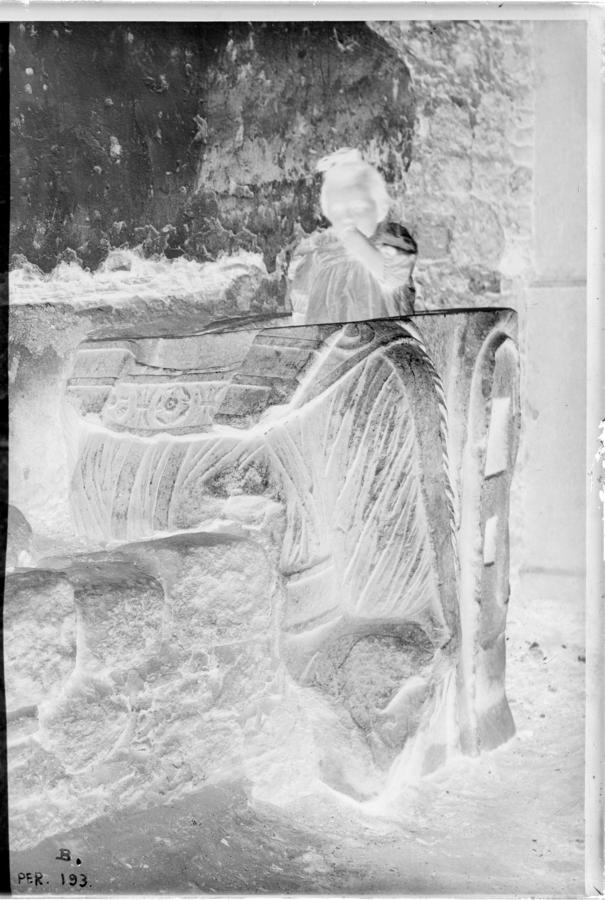

Another example of the same photograph but without the retouches, and with the child clearly visible in both views, is also preserved in the Antikensammlung on a similar card mount, although this one is devoid of inscriptions (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Upper body of a colossal double statue from the Red Hall in Pergamon, unidentified photographer, 1900, albumen print on cardboard mount, 17,1 x 23,3 cm (photo), 24.4 x 30.8 cm (cardboard), Antikensammlung, SMB, inv. no. FA-Perg34-0003.

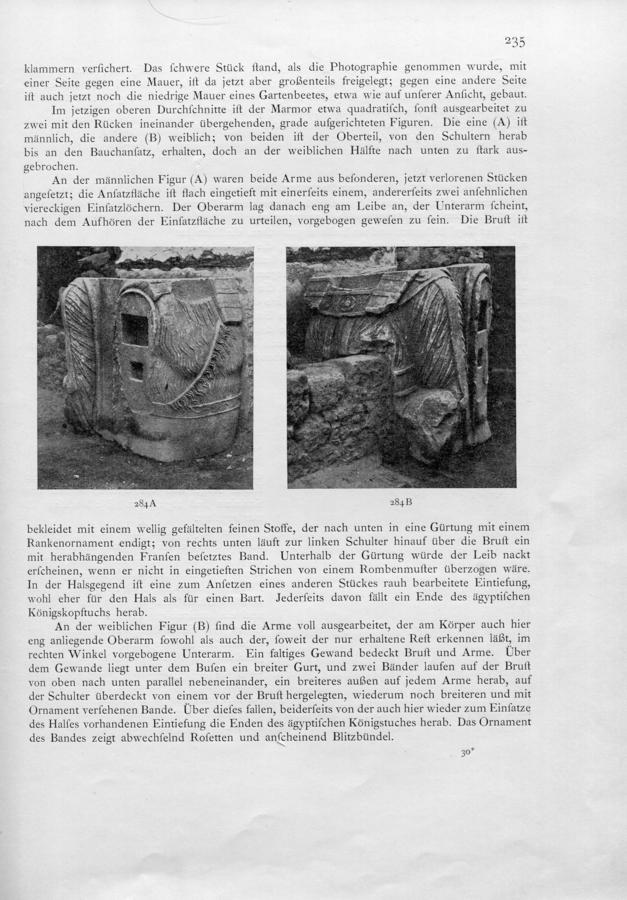

The working copy was evidently the other retouched photograph (see Fig. 1) and the successive annotations were placed on the card mount of this. Some of these annotations, together with the penciled lines and arrows on the card mount to the right and left of the photograph marked “0,12” and the long penciled bracket above the image, define a portion of the photograph, clearly in preparation for its reproduction in a publication. Indeed, the inscriptions “Perg. VII 2, Abb. 284 A” and “Abb. 284 B” written in ink below the two images in Fig. 1 refer to illustrations in the publication of the excavations of Pergamon, more precisely to volume 7, part 2, of the Altertümer von Pergamon, the monumental edition documenting the results of the campaigns (Winter 1908), and in particular figs. 284 A & B on p. 235 (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Alexander Conze, entry no. 284, “Torso,” in Winter (1908, 234–236, here 235).

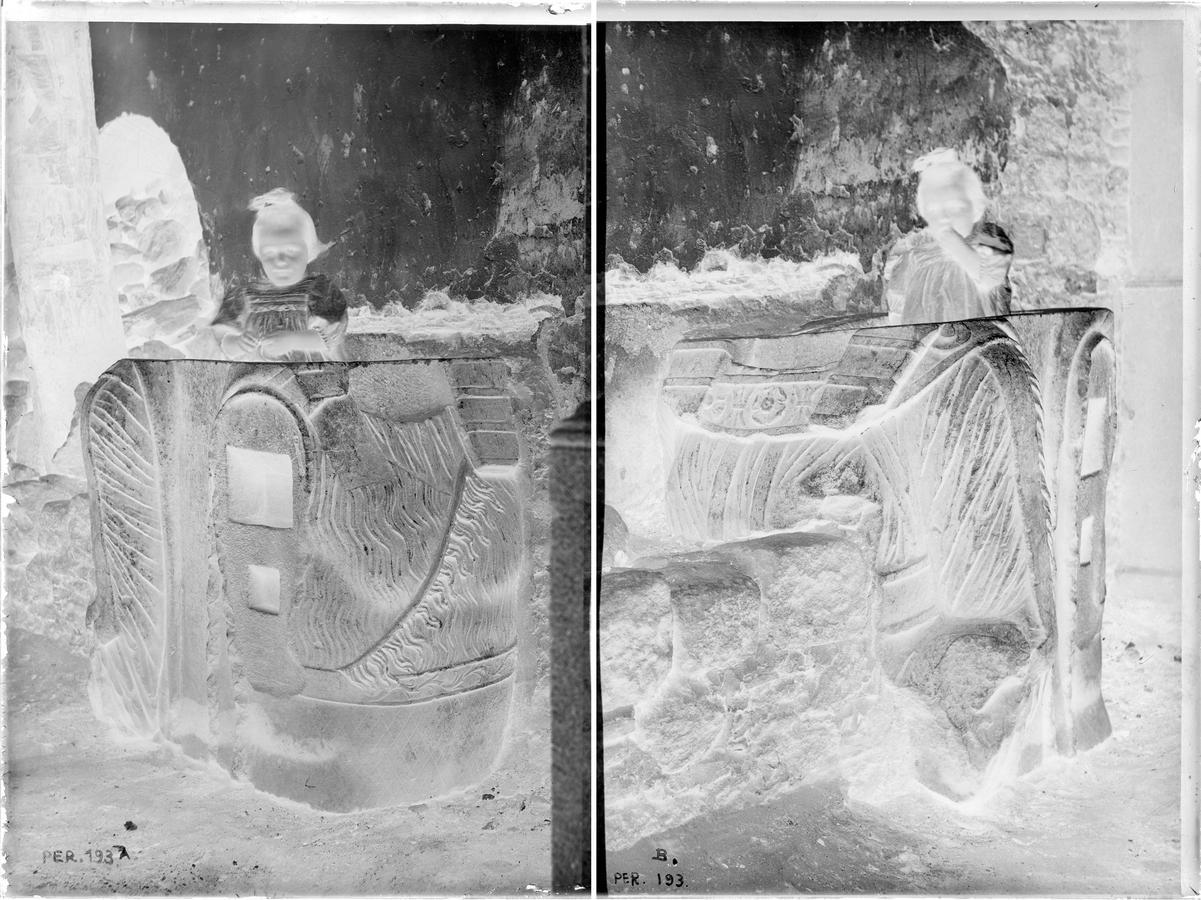

Let us briefly recapitulate some historical data relating to the German exploration of the site (Hübner 2004; Kästner 2011). The first systematic excavations at Pergamon were conducted by the Königlich Preußische Museen, now the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, with annual campaigns between 1878 and 1886. Alexander Conze, who as Director of the Antique Sculpture Collection (subsequently Antikensammlung) in Berlin had initiated the excavations, was appointed General Secretary of the Archäologisches Institut des Deutschen Reiches (subsequently Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, DAI) in 1887. In this new position, Conze initiated the second period of campaigns in Pergamon (1900–1911), which was conducted under the aegis of the DAI (Athens section). The negatives of the two views are consequently in the archive of the DAI in Athens (see Fig. 4 and 5, side by side in Hyperimage).

Fig. 4: Negative of the photograph in figs. 1 and 2, left part, 18 x 24 cm (glass plate), Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Athens, inv.no.D-DAI-ATH-Pergamon-0193A.

Fig. 5: Negative of the photograph in figs. 1 and 2, right part, 18 x 24 cm (glass plate), Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Athens, inv.no.D-DAI-ATH-Pergamon-0193B.

The key role played by Conze and the DAI also explains the above-mentioned stamp “Kaiserlich Deutsches Archaeologisches Institut Central-Direction Berlin”: in its journey from Pergamon to the Antikensammlung, this photo-object probably passed over his desk.1 Institutional history and personal histories are intertwined: both left their traces on the photo-object.

Fig. hicollage1_1

This second period of excavation campaigns, directed on site by Wilhelm Dörpfeld, also entailed inspections of the surrounding territory of ancient Pergamon and, in particular, the modern town of Bergama at the foot of the Acropolis. Here, in the Greek quarter, in the house of a certain Johannis Kaiserli, the torso of a colossal double-sided statue was documented in 1900. According to the owner of the house, the statue came from the complex of the “Red Basilica” (in Turkish: Kızıl Avlu), originally a temple of the Hadrianic period dedicated to Egyptian deities.2 The torso was published, as we have seen, in volume 7, part 2, of the Altertümer von Pergamon (Winter 1908, 234–236), illustrated by the two photographs described above (see Figs. 1 and 2). Both the annotations on the mount and the 1908 publication, which are the sources for all the information presented here, state that the cavity in the torso (the one in which the child was placed at the time the photograph was taken) is modern; it had been hollowed out of the sculpture to convert it into a water tub. We have no information on the identity of the child—perhaps a child or grandchild of Johannis Kaiserli? We know that for the excavation campaign of 1900–1901 the photographer Rudolf Rohrer joined the team in Pergamon (Hübner 2004; Krumme 2008),3 but it is also known that Dörpfeld himself very often picked up the camera and used it himself (Klamm 2017, 226), so the “authorship” of the photograph remains uncertain.

If we were to limit ourselves to examining this photograph as a purely referential image of the object represented, we would have to agree with Daniel Arasse that “on n’y voit rien” (Arasse 2000). Only if we consider FA-Perg34-0002 together with its mount and all its annotations and traces as a material object—indeed, a photo-object—that exists in space and time, and in social and cultural contexts, does its epistemological potential unfold (Caraffa 2011). Analyzing its technique, materials, and form, deciphering its inscriptions, linking this photo-object with others, and studying it more widely in relation to institutional history, archival and academic practices, and, not least, the history of the individuals involved, their interests and their affects—these are just some of the actions afforded by FA-Perg34-0002. Immersing ourselves in the world of FA-Perg34-0002, among other things, would paint a more precise picture of the undoubtedly asymmetrical relations that existed between the human actors involved, conditioned by the latently colonial context of the excavations.

From my point of view, its potential also consists in being able to test the methodological tools offered by the material approach in photography studies. As an art historian, I deliberately chose to open this publication by commenting on a photograph associated with another academic discipline, in this case, archaeology, and coming from another photographic archive and not from the Photothek of which I am in charge. FA-Perg34-0002 had already been identified as a particularly eloquent photo-object, in the true sense of the word, since it has a lot to tell us if we are willing to listen to what it has to say and do not limit ourselves to its visual content. In fact, the image had already been included in the KHI’s online exhibition Into the Archive4, which was one of the first outputs of our collaborative project. The program of the conference “Photo-Objects. On the Materiality of Photographs and Photo Archives in the Humanities and Sciences”5 (the contributions to which form the basis of this publication) was conceived as a kind of facsimile of FA-Perg34-0002.

1.2 Photo-Objects

All these steps in the process, right down to the potted history of the image I have presented above, have contributed to the construction of a new narrative around FA-Perg34-0002. Photo-objects are dynamic and unstable not only in their historical but also in their current dimension, and everything we do or say about them will make a further contribution to their formation and transformation. The material traces on and of this photo-object will continue to be studied and to shed new light, and new clues will no doubt emerge from the archive of the Antikensammlung to help us reconstruct the “photography complex” of FA-Perg34-0002 (Hevia 2009). But this close reading should in the meantime help us to introduce the premises and objectives of the project “Photo-Objects. Photographs as (Research) Objects in Archaeology, Ethnology, and Art History”: photographs are not only images, but also historically shaped three-dimensional objects. They have a physical presence, bear traces of handling and use, and circulate in social, political, and institutional networks. Beyond their visual content, they have to be acknowledged as material “actors,” not only indexically representing the objects they reproduce but also playing a crucial role in the processes of meaning-making within scientific practices. Thus, photographs lead a double existence as both pictures of objects and material objects in their own right.

The “Photo-Objects” project, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), was coordinated by the Photothek at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, Max Planck Institute (represented by myself and Julia Bärnighausen), and partnered with the Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Martin Maischberger and Petra Wodtke), the photographic collection at the Kunstbibliothek (Art Library’s Photographic Collection), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Ludger Derenthal and Stefanie Klamm), as well as at the Institut für Europäische Ethnologie (Institute for European Ethnology), Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (Wolfgang Kaschuba and Franka Schneider). The focus of the three-year project (March 2015 to March 2018) was on techniques and practices of scholarly work on and with photographs from a transdisciplinary viewpoint. The project involved four different photo archives and photographic corpora: the photographic documentation of applied arts with a focus on art trade at the Florentine Photothek; the documentation of works of art and monuments in architectural photographs from the US and Europe around 1900 at the Kunstbibliothek’s photographic collection in Berlin; archaeological excavation campaigns in Asia Minor and their photographic documentation at the Collection of Classical Antiquities (the corpus to which FA-Perg34-0002 belongs); and ethnographic photographs of the Hahne-Niehoff-Archiv at the Institut für Europäische Ethnologie.

The premises and aims of the project were also discussed during the conference “Photo-Objects. On the Materiality of Photographs and Photo Archives in the Humanities and Sciences,” held at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz in February 2017.6 Of course, the use of photographs as research materials is not a practice limited to art history, archaeology, and ethnology. Most scientific and scholarly disciplines rapidly adopted photography as an important research tool to document everything from excavation sites, costumes, and artworks in museums to snowflakes under a microscope. It was through photographs that these objects of research were detached from their original surroundings, converted into standardized and transportable formats, newly contextualized, and made comparable. In particular, the material qualities of photographs have shaped their adoption in the various disciplines by affording certain types of use. Thanks to the ways in which photographs were handled or processed, and the inscriptions or annotations on their mounts, photo-objects could be classified according to specific taxonomies and stored in files, boxes, cabinets, and shelves; thus, they were made applicable to the sciences and humanities.

Concurrently, the rhetoric of the presumed neutrality of photography as a chemical-mechanical process fed the notion of photographs as evidence, satisfying the positivistic demand for “objectivity.” The formation, development, and definition of many academic disciplines is therefore inconceivable without photography. These processes were encouraged by the foundation of specialized photo-archives as interfaces of technology and science. Since the second half of the nineteenth century, enormous masses of documentary photographs have been gradually accumulated in universities, research institutes, and museums (Mitman and Wilder 2016). These archives were and still are laboratories of scientific thought, where the humanities and sciences have developed their methods and practices. Here, objects of all kinds are part of a dynamic and material system of knowledge, interacting with and reacting to each other—from photo-objects in their various manifestations to storage facilities, card catalogs, inventory books, reference lists, prints, and illustrated publications. The network of interactions also comprises human agents such as photographers, archivists, and researchers.

The papers presented at the conference in Florence and now forming the basis of this publication have the material approach as their common denominator. They make use of this shared approach in order to analyze the epistemological potential of analog and digital photographs and photo archives in the humanities and sciences from a comparative viewpoint. Taking the material aspects of photographic practices as their starting point, the papers deal with the circulation and distribution of photographs, the construction of methods through the handling and use of photographs in the various disciplines, the arrangement, classification, and working processes in place in photo archives, as well as photographs in different institutions (i.e., archives, museums, research institutes, and laboratories). The conference was an occasion for us to test and discuss our ideas with colleagues from various disciplines. Moreover, this publication also represents an opportunity to briefly sum up the state of the art of research on photography and materiality from a critical and self-reflexive perspective.

1.3 Photography and materiality

The material approach in photography studies is relatively recent; it only began to be developed in the 1990s. The first seminal publications appeared in the sphere of British anthropology (Edwards 1992) and are linked to the need to come to terms with the colonial legacies of the discipline. Some underlying ideas had been formulated in the 1980s in the context of the material turn (Miller 1987; 1998). This stimulated the serious consideration of the physical and material aspects of photographs, including their forms of presentation and archival storage. The phenomenological approach of the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (Bourdieu 1965; 1990 as well as Bourdieu 1972; 1977) has also had a fundamental impact. “The physicality of the photograph is not articulated by those consuming it. It constitutes part of the unarticulated ‘habitus’, that daily praxis within the material world, a ‘household ecology of signs’ in which social actions take place” (Edwards 1999, 234 quoting Bourdieu 1977). The material aspects, consequently, cannot be separated from social practices and cultural expectations—for instance, the expectation of “objectivity” with regard to documentary photographs collected as research tools in the context of a particular discipline. A leading methodological approach to addressing issues such as this has been the biographical model with the idea of a “social life of things,” which can be traced back to the studies of Appadurai (1986) and Kopytoff (1986): a thing cannot be reduced or confined to a single moment of its existence (for example, the instant of the shutter’s click) but must be considered within a continuous and fluid process of production, exchange, and consumption.

Tracing the “concrete historical circulation” of artifacts enables us to reconstruct their changing “meanings […] inscribed in their forms, their uses, their trajectories” in space and time (Appadurai 1986, 5).7 By recognizing that objects have a life of their own and hence play an active role in social relations, the biographical model indirectly led to the concept of the agency of objects later elaborated by Alfred Gell (1998). According to Gell, visual artifacts exercise agency through an “enchantment of technology” (1992) which permits them to enter into relations with persons by arousing feelings of love, desire, hate, or fear. These ideas were effectively applied to photographs by Christopher Pinney (1997) and Elizabeth Edwards (1999; 2001). Another substantial contribution came from a different route, from the field of historical geography and Canadian archive studies, in particular thanks to the work of Joan M. Schwartz (1995). Deborah Poole (1997) introduced the notion of “visual economy” to describe the global circulation of images as commodities. Geoffrey Batchen (1997, 2) was among the first to confront art historians with the idea that “the photograph is an image that can also have volume, opacity, tactility, and a physical presence in the world.” A phase of consolidation roughly between 2000 and 2005 helped to diffuse this material approach beyond the confines of disciplines and Western academia.8 Studies on photography and materiality are currently flourishing and rapidly growing, as shown by the incredible number of abstracts we received in response to our call for papers on “Photo-Objects.”

I have attempted elsewhere (Caraffa forthcoming) to provide a broad historical and critical discussion of the material approach in photography studies as well as a more exhaustive survey of recent contributions;9 many more besides are cited in the papers included in the present volume. It may be worthwhile to extend the picture by recalling that photography and materiality studies are by definition transdisciplinary, albeit rooted in material culture studies, and so they should be considered against a wider cultural backdrop.

Indeed, in the same years during the 1980s in which the material turn was taking shape, a series of studies and approaches from different disciplines began to challenge some canonical concepts that had characterized photography studies up until this point. In the late 1970s, postmodern critics had started questioning the existence of a single photographic meaning and highlighting the intrinsic ambiguity of photography (Crimp 1989; Solomon-Godeau 1984).10 Attention, however, was still focused largely on art photography. Authors such as John Tagg (1988), Victor Burgin (1982), Allan Sekula (1982; 1989), John Berger (1974; 1980), and Martha Rosler (1989) widened its scope by subjecting all photographic cultural production—including mass media, documentary photography, and other regulatory social practices—to an overall critique. These studies helped pave the way for the material approach, anticipating one of its benefits, namely, that of overcoming the conventional hierarchies of photographic value based on uniqueness and authoriality.

This idea of photographs as unique art works, which excludes a major part of the actual photographic production, is rooted both in museum systems and in art historical academia. Consequently, within the field of art history, it was particularly necessary to prepare the ground for a different consideration of (photographic) images: not only expressions of the artistic intentionality of an author but also active entities in society. One of the seminal studies in this direction was by Baxandall (1972), who showed that the public addressed by Italian Renaissance painters was able to decipher their works thanks to a series of shared social experiences.

The concept of the power of images (Freedberg 1989), heralded in a series of art historical studies, was expanded by W. J. T. Mitchell in the sense of a pictorial turn (Mitchell 1994; see also Stafford 1999).11 Postulating the central role of images in culture and society meant highlighting the truly visual, non-textual performances of images, going beyond the linguistic approach to culture that suggested interpreting and “reading” the entire world (and thus also photographs) as a text.12 By posing the significant question “What do pictures want?,” Mitchell (1996; 2005b) arrived at a theory of the agency of images and also insisted on their multisensory nature (Mitchell 2005a): images cannot be reduced to pure opticality (see also Bal 2003). Mitchell’s work influenced and confirmed the path taken by other contemporary studies on photography and materiality. Similarly influential was the German art historian Hans Belting who, in his anthropology of images (Belting 2001; 2011), devoted particular attention to the relationship between images and bodies.

Another important contribution came from the field of visual culture: this concept “implies the possibility of inventing different kinds of historical voices” (Batchen 2008, 127). It encouraged researchers to go beyond the traditional mode of concentrating on single photographers as auteurs and suggested placing the emphasis on photographic practices and genres or the perspectives of the embodied viewer (e.g. Smith 1999; Mirzoeff 2003).13 In the meantime, interest in photographic practices as an industrial and commercial phenomenon (McCauley 1994) had opened the way for considering photographs as commodities and, consequently, social objects. Authors such as Crary (1990) and Mitchell (1992) had highlighted the historical dimension of vision and representation technologies.

During the same period, the advent of digital technology led to a distancing from analog photography, which could now be historicized as a medium of the past. The history of science began to query the link between technologies of representation and the concept of scientific objectivity (Daston and Galison 1992; Tucker 2005; Daston and Galison 2007). At the same time, feminist-oriented studies such as those by Haraway (1991) had even more radically begun questioning the concepts of nature, science, and objectivity, criticizing the separation between humans and non-humans. Terry Cook and Joan M. Schwartz (Schwartz 2002), among others, used Haraway’s conceptual tool of “situated knowledge” to develop a new postmodern archive theory and practice. Their insistence on the archivist’s role as a “historically situated” actor (Schwartz 1995, 62), not as the neutral guardian of the archive, has been of fundamental importance to studies on photography and materiality: photographic archives are places of interaction among various actors (archivists and users) and of technological and professional practices that are not limited to preserving but rather that shape photographic documents and their meanings over time. Stripping photographs of their presumed objectivity is equivalent to putting them back into circulation as autonomous objects within the network of agencies described above.

The intellectual and cultural climate described here was dramatically influenced by actor-network theory (ANT) and assemblage thinking. ANT was developed from the 1970s onward in the context of science, technology, and society studies (STS) (Callon and Latour 1981; Latour 2005). It took as its starting point a critique of the separation between nature, culture, and society based on modern concepts of scientific objectivity and causal determinism. For ANT, there are no discrete and independent entities, but only relational results and effects. The networks are heterogeneous and hybrid, comprised of both human and non-human elements (animals, objects, and the practices of daily life). Each of these exerts an agency (as actor or actant) on which the network’s stability depends. Through their performances, the actors interact among themselves in a process of continuing translation; the networks, in fact, never have a fixed morphology. ANT’s emphasis on processuality is explained in storytelling: the construction of hybrid actor-networks is a narrative of how networks take shape and are stabilized (or perhaps not), engaging new actors, persons, and things.14

The picture traced above cannot claim to be exhaustive. But the reference to networks and storytelling takes us back to the history of FA-Perg34-0002 with which I began this introduction. The network of this photo-object (see Fig. 1) is not limited to the negatives, other positives, and their circulation on printed media (see Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5). It also includes the German archaeologists who documented and studied the torso in Bergama, the photographic techniques and archaeological practices around 1900, as well as Johannis Kaiserli, in whose house the statue was found, and the child playing in the torso’s cavity. The structures of the Antikensammlung and their changes over time, together with the storage and numbering systems, are just as much part of the network as the transformations that occurred within the framework of the “Photo-Objects” project.15

Networks are never stable and always expanding. To come to terms with these processes of continuous expansion and give form to their narratives, it is useful to begin focusing on one knot of the network—in our case, FA-Perg34-0002. It was Elizabeth Edwards (2001, referencing Geertz 1973 and Ginzburg 1993) who programmatically proposed the technique of close reading in the interpretation of photo-objects. Microhistories and close-up views help us grasp what escapes broader analyses; it is a concentration on “little narratives” (Hoskins 1998, 5) which, ultimately, can also tell us a great deal about the big narratives. In this sense, photo-objects like FA-Perg34-0002 also serve as cross-references, pars pro toto, to the archive in which they are preserved and in which an important part of their biography is played out. This dimension is fundamental to our project and is touched upon by many of the papers published here, which take into consideration masses of often anonymous photographs that have gradually accumulated in archives and museums.

Close readings of this kind also serve as a way for many of us to raise the awareness of our political and institutional partners, to whom we can say: “Just look at what extraordinary objects are hidden away in a dusty photo archive!” All the more reason for not shutting them down or getting rid of their holdings—a real risk in the current institutional situation still characterized by the rhetoric of the digital revolution and dematerialization. However, this practice of closely examining selected photo-objects prompts us to reflect on a particular danger that is inherent in the material approach: that of their reduction to museum objects. If we concentrate on individual exceptional photo-objects, our aim should be not to extrapolate them from their archive and place them in a glass case, forgetting the rest. If we do so, we would end up perpetuating the museographic approach that has hitherto fueled the opposite phenomenon, namely, the low visibility of many “functional” photo collections (Edwards and Lien 2014; Edwards and Morton 2015). For this reason, the concept of ecosystem developed by Elizabeth Edwards is extremely useful because it highlights interactions and definitively breaks traditional hierarchies of value.

1.4 The papers in this publication

This leads us to the various contributions to this publication. Elizabeth Edwards, in her introductory essay (Chapter 3), emphasizes the dual nature of photographs as collectable objects at the museum level and as objects dependent on museum management. We therefore find institutionally recognized collections of photographs in museums and in archives, as well as “non-collections” which exist materially but are invisible at the institutional level. Expanding her recent reflections on the concept of photographic ecosystem (Edwards and Lien 2014),16 Edwards offers a perceptive critique of institutional practices nowadays. She points out the current tendency toward the “insurrection” of non-collections. In the final analysis, this insurrection is stimulated by the profusion of recent studies on photography and materiality to which the present publication is also intended to contribute.

With her chapter on the “sciences of the archives,” Lorraine Daston provides the scholarly and historical background to the conference and its publication from the point of view of the history of science (Chapter 4). In the nineteenth century, the universal aspirations and the quest for mechanical objectivity were common to humanities and natural sciences and gave rise to the formation of colossal archives which siphoned off funds and energy from research proper. In her study, Daston concentrates in particular on two monumental archives founded to support Big Science: the paper squeezes of Latin inscriptions of the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum and the astrophotographic glass negative plates of the Carte du Ciel. Following the destinies of these two projects to the present, Daston pinpoints the accidental traces that have in the meantime emerged from these archives and that are able to respond to questions unforeseeable at the time of their formation.

The first section of the publication is headed “Into the Archive.” It is an invitation to continue this immersion in the reality of photographic archives. İdil Çetin offers a lively ethnography in miniature of her doctoral research on photographs of Atatürk (Chapter 5). Her intervention is focused on the experience of the ethnographic self in the non-territory of Turkish state archives. Suryanandini Narain poses the question of what happens when family snapshots leave their natural habitat and take on new connotations in an archive (Chapter 6). Her study examines, inter alia, the various objectives and different degrees of institutional formalization of some Indian archives presented as case studies. The interpretations of photographs they permit are always incomplete. Katharina Sykora reports on a find she made in the holdings of the Photothek of the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz: a group of photographs that document a performance celebrating the 250,000th accession to the Photothek in 1969 (Chapter 7). Sykora methodically reconstructs the event and subtly analyzes the material agency developed on various levels by the photographs and their archons, deducing from them an invitation to scholars of photography to handle their objects of research with equal freedom and creativity.

Hands serve not only to handle photographic objects but also to perform surgical operations and to work in a conservation laboratory: activities scrutinized in the next section of the book, entitled “Getting One’s Hands Dirty.”17 In contrast to the purely postcolonial approach that characterizes many studies on the photography of the Middle East, Zeynep Çelik invites us to consider an alternative point of view, that of late nineteenth-century modernity in the region (Chapter 8). The album of medical photographs she has studied was produced in Istanbul’s Haseki women’s hospital during the 1890s. The photographic portraits are of women mainly of humble origins, who display the scars on their abdomens and the jars in which the tumors surgically removed from them are preserved. They call into question, among other things, what were considered the conventions for representing women in a Muslim society. Then Omar Nasim analyzes photo-objects in astronomical practices with a focus on their handling within the context of apparatuses (Chapter 9). With the introduction of astrophotography, the apparatus of astronomers has been transformed from a night spent in the observatory to the analysis of the fragile glass plate negatives in one’s own office. Nasim explores the tensions between photo-object and thing using contemporary contradictions such as the removal of historic annotations from negative plates in the field of digitalization campaigns. The material approach is particularly useful because it shifts the focus to the photographic “non-collections” discussed by Edwards (Chapter 3). It is also useful to enter into dialogue with authorial, artistic, and museum photography. In their joint study on the Corridors series by the artist Catherine Yass (Tate London), Haidy Geismar and Pip Laurenson are able to make different epistemologies of the photo-object dialogue with each other in a productive way, from the point of view of both anthropology and conservation (Chapter 10). In the final essay in this section, Christopher Pinney introduces us to the world of the digital circulation of images of sacred cows in India (Chapter 11). Pinney reminds us that the digital is a physical phenomenon in itself. Yet the photographs of Indian cattle have even deeper material implications, including the killing of citizens of Muslim faith accused on social media of having slaughtered cows. The essay shows it is possible to dirty one’s hands even by handling digital photographs.

The question of hierarchies of values is a recurrent theme in this publication. However, some of the papers address this aspect more directly in the section headed “Systems of Value.” Focusing on the Photothèque of the Musée de l’Homme founded in Paris in 1938, Anaïs Mauuarin calls into question the dichotomy generally postulated between agencies responsible for commercializing images and institutions dedicated to the archival storage of photographs for research (Chapter 12). The ethnographic photographs from the Photothèque were considered not only as scholarly evidence, but also as commodities, with consequences for the material arrangement of the collection and the standardization of images. Mauuarin analyzes and interprets the various levels of codification of data on the card mounts in particular, where the scientific value and the commercial value of photographs intersect. Then Lena Holbein examines the photo book Evidence published by Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan in 1977 and the photographic exhibitions linked with this (Chapter 13). The artistic and curatorial strategies of Evidence are revealed as playful ways of turning archival practices upside down, of negating archival conventions; they have the result of underlining the intrinsic value of photographs as images and not as documents or evidence. The different modes of cataloging the photographs then used by Mandel and Sultan in two digital collections show a similar oscillation between intrinsic artistic worth and original documentary value. The question of the value of individual photo-objects is unavoidable in the context of duplicates, as discussed by Petra Trnková in her paper on eight “almost identical” photographs by Andreas Groll showing the town hall in the Old Town of Prague and dating back to the 1850s–1860s (Chapter 14). A detailed analysis of the material qualities of each of the positives is followed by the reconstruction of the collection to which they originally belonged and its institutional vicissitudes. The “rediscovered” present is linked to the contingent fortune of photo-objects in current research, an unstable or precarious one according to Trnková, precisely because it is linked to a system of not wholly canonized values.

This leads us directly to the last section of the publication dedicated to processes of “Canon Formation and Transformation” that occur in photographic archives and in their numerous manifestations, including catalogs. Kelley Wilder applies the material approach to the photographic card indexes in use both in museums and in the commercial sphere—the precursors of digital catalogs (Chapter 15). Catalogs represent the interface between the collection and the public. An encounter or clash between the different materialities of photographs and the complex structures of the textual information that accompanies (or sometimes contradicts) them takes place in the files of these catalogs. Wilder identifies a historical tendency towards the assimilation and interaction of text and image in such catalog entries, which become photo-objects in their own right. It is no coincidence that the commercialization of lantern slides for art historical teaching, pioneered by Bruno Meyer in Germany, began with a printed catalog of 1883. Maria Männig proposes a material history of Meyer’s slides, their production and distribution, and his business interests in marketing them, which ultimately met with little success (Chapter 16). Männig’s contribution places the slides of Meyer and Herman Grimm in the dialectic between “old” and “new” media. The sale catalog, which for Meyer had the status of a scientific publication, prefigures later art historical slide libraries in its systematic arrangement. The most iconic photographs in the history of archaeology certainly include those taken by Howard Burton of the excavations of the tomb of Tutankhamun. However, in the view of Christina Riggs, it is the archive formed by all these photographs (preserved for historical reasons in two only partially overlapping collections in Oxford and New York) that represents the mirror and the founding myth of archaeology (Chapter 17). Riggs traces the history of these two collections right to the digital present. It is archival practices, she underlines, that transport the traces of the structures of power in which the photo-objects were created and used; and in disciplines such as archaeology, the structures in question are those of colonial power.

This series of papers is concluded with the final reflections of Joan M. Schwartz (Afterword). After 25 years of studies on photography and materiality, Schwartz begins by stating that an international interdisciplinary community concerned with photo-objects finally exists: while in other academic contexts, many of the papers would have been at the margins of the scholarly discourse, they found a fitting environment at the conference in Florence and in the present publication. Schwartz rounds off the discussion with some closing remarks on the archival dimension and the scholarly customs that still very often characterize the use and reception of photographs in archives. Researchers should approach photo-objects not only by asking for (visual) answers but also by being prepared to listen to these and to the questions that photographs pose.

1.5 A transdisciplinary approach

Finally, looking back at the joint contribution by Julia Bärnighausen, Stefanie Klamm, Franka Schneider, and Petra Wodtke that opens this publication (Chapter 2), the aim, or at least one of the aims, of this collective study is to express the great potential of the transdisciplinary work conducted as part of the “Photo-Objects” project. Yet the comparative analysis of the processes that take place in such heterogeneous archives—and that give rise to the continuous formation and transformation of photo-objects—always ends up reinforcing their mutable and unstable character. This ought not to be considered a topos, or even a commonplace. Nor should its reiteration be regarded as superfluous, because many members of the scientific community that study and/or use photographs and archives continue to believe that photographs and archives are stable entities. Bärnighausen, Klamm, Schneider, and Wodtke also test the notion of “itinerary” in relation to the idea of a biography of photographic objects.

This attempt is linked to a wider transdisciplinary debate that is in progress in our field of studies. Reflections on the index and on the agency of photo-objects have given rise in recent years to alternative concepts such as that of the “performative index” proposed by Margaret Olin (2012, 69), or of “presence,” on which Elizabeth Edwards (2015; 2016) as well as Haidy Geismar and Christopher Morton (2015) have worked.18 But what about the social lives of photographs? The biographical model derived from Appadurai (1986) and Kopytoff (1986), as we have seen, has been adopted ever since the first studies on photography and materiality (Pinney 1997). Right from the outset, Edwards has fended off a frequent criticism of the biographical model that would entail the death of the object: those photographs “are not dead in the stereotypical cultural graveyard of the museum and archive, but are active as objects and active as ideas in a new phase of their social biography” (Edwards 2001, 14). Proponents of the biographical model often speak of biographies (in the plural) precisely to avoid the idea of a death that must perforce end the life of photographs—a conception that is, moreover, rooted in European Christian culture. Perhaps other cultures have fewer problems with a cyclical view of the biographies of objects.

The wide diffusion of the writings of Latour has more or less directly influenced many authors (Geimer 2010). For instance, James Hevia (2009) derived the notion of the “photography complex” from ANT. Pinney (2005, 266) speaks of trajectories and of compressed performances. Meanwhile, the biographical model has been called into question even by some of its initial supporters, for it suggests linearity and therefore cannot necessarily embrace complex networks of relationships (Edwards and Morton 2015, 9–10). Various proposals for alternative concepts, such as interaction (Knappett 2011), entanglement (Hodder 2012), and itineraries (Hahn and Weiss 2013), have come from the field of material culture studies. In coming to terms with photo-objects and telling their histories, studies of photography and materiality seem to make unprejudiced use of all these expressions and methodological tools.

There is another field that requires us to rid ourselves of many prejudices: namely, the relation between analog and digital. The material approach provides us with many arguments in favor of the preservation of analog photo archives, which cannot be substituted by their digital surrogates. This is argued also in the “Florence Declaration – Recommendations for the Preservation of Analogue Photo Archives”19 launched in 2009.20 Moreover, we need to develop digital tools that do not reduce photographs to their purely visual content but also take account of their materiality. This online publication, entrusted to the Edition Open Access of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, is certainly an occasion to experiment with new digital visualization and interaction tools. Hyperimage (as one way of handling photo-objects in the online publication) was made possible by our colleagues at bitGilde in Berlin. Above all, however, it is essential to extend our attention to the materiality of the digital itself. This is indeed one of the major themes of the future in our postdigital society, ever more mindful of analog processes in which the digital is expressed.

Digital media shape the acts of our memory—individual, familial, and collective (VanDijck 2007; Rose 2010). The digital images that circulate in the social networks have the capacity to impact on people’s lives and to reunite individuals in communities: they are therefore far from “immaterial” (Were and Favero 2013; Miller 2015; Walton 2016). The material approach has highlighted the multisensoriality that characterizes the photographic experience.21 This aspect, together with interaction with the (engendered) body and the gestures connected to producing and using photographs, has also been studied in the digital field (Favero 2014; Frosh 2015). Even without wishing to consider the problem of digital rubbish (Gabrys 2011; Maxwell, Raundalen, and Vestberg 2015), the use of digital photography presupposes the need to avail ourselves of a variety of objects (perhaps increasingly less computer monitors and increasingly more tablets and smartphones, perhaps even digital tables or walls, or even watch screens—but still hardware) whose use is also linked to a specific gestuality. Paolo Favero (2017; 2018) defines the actions performed with digital images as a continuous performance. He definitively deconstructs the idea that the transformations that take place in the digital habitat lead to a progressive “dematerialization”: there is a series of technologies (such as 3D printers and wearable technologies) that will increasingly be used to translate abstract images or ideas into material objects. These technologies transform the relations between the vision, body, and senses to which analog photography has accustomed us. They also question the association between photography and time, since digital photographic practices in the social media no longer appear to register the past; they seem instead to comment on a present in a constant state of becoming (McQuire 2013; Miller 2015; Miller and Sinanan 2017). Some of the papers in this publication address these phenomena.

I would like to conclude with some comments on how our own archives and methodology are adjusting to the transdisciplinary approach. The photographic materials with which we interact in the four photo archives involved in this project are clearly very different in kind. At the outset, we were slightly concerned about this lack of homogeneity, but now we are firmly convinced that it is one of the assets of the project. The transdisciplinary approach produced key results also thanks to the format of what is known as “Tandem-Forschung”: our collaborators periodically organized tandem meetings of two or more scholars at a time, one of whom invites the other to a few days’ immersion in his or her “own” archive.22 The exercise begins as a guided visit and ultimately becomes a shared process. All participants learn about the materials and working methods of the others as well as how to see their own objects of research through the eyes of their colleagues, who each contribute their own ideas. We have thus learned to consider our own work not as something separate from photo-objects, but as a transformative addition to their trajectories. By working on photographs and archives in their materiality, we have strengthened our sensitivity to the connections that bring people closer together in what Edwards (2015, 241) calls “the photographic encounter.”

In the case of the Hahne-Niehoff-Archiv at the Humboldt Universität, the individuals in question are those portrayed and reified in photographs that were intended to serve an ethnology with an explicitly racist stamp. This collection of ethnographic photographs documenting folk festivals in villages in central Germany between the early 1920s and 1945 should prove the continuity of German culture as part of the strongly ideologized scholarly panorama of proto-Nazi and Nazi Germany. This clearly is the most shocking and least innocent of the photographic corpora on which we were working in the framework of this project (while recognizing that no archive is innocent). Apparently, photographs of Baroque mirrors or American domestic architecture or archaeological ruins are far more innocuous—apart from the fact that here, too, human beings may appear, as we have already seen in FA-Perg34-0002 (see Fig. 1). My personal punctum , what makes me uncomfortable about this photograph is not so much the head of the child as the exclamation mark after the words “Das Kind zu tilgen!”: The child is to be erased! But we have learned that all of our photo-objects may be “touching photographs,” as Olin (2012) would call them.

The critical approach that needs to be applied to the Hahne-Niehoff-Archiv has in fact made us far more receptive to the disturbing elements that may crop up even in what, at first sight, may seem the most inoffensive photographs. Pinney (2003, 6; 2008, 2) and Poole (2005, 164) have called it the “noise” and “excess” of photography. Edwards (2001) has spoken of “rawness” and more recently of “abundance” (2015, 237). To the photographic encounter we should add the “archival encounter” (Campt 2012, 20) to which Joan M. Schwartz has contributed so much.23 Photography, materiality, and people encounter each other in the archive, which is simultaneously an orderly and a multitemporal space. It is here that the academic and archival practices of our predecessors and those of the present emerge. Yet affects are also revealed: not least our own affects, which have in turn become part of the project. Affects and the question of positionality were among the components of the exhibition “Unboxing Photographs. Arbeiten im Fotoarchiv” that concluded our project (Berlin, Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, at the Kulturforum, February 16 to May 27, 2018).24

The exhibition itself was not a simple result, but an essential part of our joint research on photo-objects (Lehmann-Brauns, Sichau, and Trischler 2010). In this exhibition we “unboxed” the boxes of photographs in our archives and displayed the daily work practices performed by generations of archivists and not least by us. We attempted to transpose into the exhibition the specific gestuality of the photographic archive (Geismar 2006) and to show, as Gillian Rose (2000) maintains, that it is the archive that “makes” the researcher. In the course of this project, we have learned to have respect for the photo-objects in their (changing) materiality. We hope we were able to convey this to visitors to the exhibition. Only if we respect photographs and are disposed to listen to them (Campt 2017) will these photographs speak to us.

1.6 List of figures

• Fig. 1: Upper body of a colossal double statue from the Red Hall in Pergamon, unidentified photographer, 1900, albumen print on cardboard mount, 16.8 x 23 cm (photo), 25.2 x 33.4 cm (cardboard), Antikensammlung, SMB, inv. no. FA-Perg34-0002.

• Fig. 2: Upper body of a colossal double statue from the Red Hall in Pergamon, unidentified photographer, 1900, albumen print on cardboard mount, 17.1 x 23.3 cm (photo), 24.4 x 30.8 cm (cardboard), Antikensammlung, SMB, inv. no. FA-Perg34-0003.

• Fig. 3: Alexander Conze, entry no. 284, “Torso,” in: Franz Winter (ed.), Altertümer von Pergamon: Die Skulpturen mit Ausnahme des Altarreliefs, vol. 7, 2: (Berlin: 1908), 234–236, here 235.

• Fig. 4: Negative of the photograph in figs. 1 and 2, left half, 18 x 24 cm (glass plate), Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Athens, inv.no.D-DAI-ATH-Pergamon-0193A.

• Fig. 5: Negative of the photograph in figs. 1 and 2, right half, 18 x 24 cm (glass plate), Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Athens, inv.no.D-DAI-ATH-Pergamon-0193B.

1.7 References

Appadurai, Arjun, ed. (1986). The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Arasse, Daniel (2000). On n’y voit rien. Paris: Descriptions.

Baetens, Jan (2007). Photography: The Question of “Interdisciplinarity”. In: Photography Theory. Ed. by James Elkins. London: Routledge, 53–74.

Bal, Mieke (2003). Visual Essentialism and the Object of Visual Culture. Journal of Visual Culture 2(1):5–32.

Bärnighausen, Julia, Costanza Caraffa, Stefanie Klamm, Franka Schneider, and Petra Wodtke (forthcoming). Foto-Objekte: Forschen in arch äologischen, ethnologischen und kunsthistorischen Archiven. Berlin: Kerber Verlag.

Batchen, Geoffrey (1997). Photography’s Objects. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Art Museum.

– (2008). Snapshots: Art History and the Ethnographic Turn. Photographies 1(2): 121–142.

Baxandall, Michael (1972). Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Belting, Hans (2001). Bild-Anthropologie: Entw ürfe für eine Bildwissenschaft. München: Fink.

– (2011). An Anthropology of Images: Picture, Medium, Body. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Berger, John (1974). Understanding a Photograph. In: The Look of Things. Ed. by John Berger. London: Viking.

– (1980). Uses of Photography. In: About Looking. Ed. by John Berger. New York: Pantheon Books, 27–63.

Boehm, Gottfried, ed. (1994). Was ist ein Bild? München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag.

Bolter, Jay David and Richard Grusin (1999). Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre, ed. (1965). Un art moyen. Essai sur les usages sociaux de la photographie. Paris: Ed. de Minuit.

– (1972). Esquisse d’une th éorie de la pratique. Paris: Librairie Droz.

– (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

– ed. (1990). Photography: A Middle-brow Art. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Trans. by Shaun Whiteside.

Burgin, Victor, ed. (1982). Thinking Photography. London: Macmillan.

Callon, Michel and Bruno Latour (1981). Unscrewing the Big Leviathan: Or How Actors Macrostructure Reality and How Sociologists Help Them to Do So. In: Advances in Social Theory and Methodology. Ed. by K. Knorr-Cetina and A. V. Cicourel. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 277–303.

Campt, Tina M. (2012). Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

– (2017). Listening to Images. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Caraffa, Costanza (forthcoming). Photographic Itineraries in Time and Space: Photographs as Material Objects. In: Handbook of Photography Studies. Ed. by Gil Pasternak. London / New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

– (2011). From Photo Libraries to Photo Archives: On the Epistemological Potential of Art-Historical Photo Collections. In: Photo Archives and the Photographic Memory of Art History. Ed. by Costanza Caraffa. Berlin and Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 11–44.

– (2017). Manzoni in the Photothek: Photographic Archives as Ecosystems. In: Instant Presence: Representing Art in Photography. Ed. by Hana Buddeus, Vojtěch Lahoda, and Katarína Mašterová. Prague: Artefactum, 122–137.

Conze, Alexander (1902). Vorbericht über die Arbeiten zu Pergamon 1900–1901. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Arch äologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, vol. 27.

Crary, Jonathan (1990). Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Crimp, Douglas (1989). The Museum’s Old/ The Library’s New Subjects. In: The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography. Ed. by R. Bolton. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 3–14.

Daston, Lorraine and Peter Galison (1992). The Image of Objectivity. Representations 40:81–128.

– (2007). Objectivity. New York: Zone Books.

Dennis, Kelly (2009). Benjamin, Atget and the "Readymade" Politics of Postmodern Photography Studies. In: Photography: Theoretical Snapshots. Ed. by J. J. Long, Andrea Noble, and Edward Welch. New York, NY: Routledge, 112–124.

Edwards, Elizabeth, ed. (1992). Anthropology and Photography, 1860–1920. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

– (1999). Photographs as Objects of Memory. In: Material Memories. Ed. by Marius Kwint, Christopher Breward, and Jeremy Aynsley. Oxford: Berg, 221–236.

– (2001). Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums. Oxford and New York: Berg.

– (2005). Photographs and the Sound of History. Visual Anthropology Review 21(1-2): 27–46.

– (2009). Thinking Photography Beyond the Visual. In: Photography: Theoretical Snapshots. Ed. by J. J. Long, Andrea Noble, and Edward Welch. London: Routledge, 31–48.

– (2012). Objects of Affect: Photography Beyond the Image. Annual Review of Anthropology 41:221–234.

– (2016). Der Geschichte ins Antlitz blicken: Fotografie und die Herausforderung der Präsenz. In: Zeigen und/oder Beweisen? Die Fotografie als Kulturtechnik und Medium des Wissens. Ed. by Herta Wolf. Berlin: De Gruyter, 305–326.

Edwards, Elizabeth and Janice Hart, eds. (2004). Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images. London: Routledge.

Edwards, Elizabeth and Sigrid Lien, eds. (2014). Uncertain Images: Museums and the Work of Photographs. Farnham: Ashgate.

Edwards, Elizabeth and Christopher Morton, eds. (2015). Photographs, Museums, Collections: Between Art and Information. London: Bloomsbury.

Favero, Paolo S. H. (2013). Getting Our Hands Dirty (Again): Interactive Documentaries and the Meaning of Images in a Digital Age. Journal of Material Culture 18(3):259–277.

– (2014). Learning to Look Beyond the Frame: Reflections on the Changing Meaning of Images in the Age of Digital Media Practices. Visual Studies 29(2):166–179.

– (2017). The Transparent Photograph: Reflections on the Ontology of Photographs in a Changing Digital Landscape. London: Royal Anthropological Institute.

– (2018). The Present Image. Visible Stories in a Digital Habitat. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Freedberg, David (1989). The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Frosh, Paul (2015). The Gestural Image: The Selfie, Photography Theory and Kinesthetic Sociability. International Journal of Communication 9:1607–1628.

Gabrys, Jennifer (2011). Digital Rubbish: A Natural History of Electronics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Geertz, Clifford (1973). The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books.

Geimer, Peter (2010). Bilder aus Versehen. Hamburg: Philo Fine Arts.

Geismar, Haidy (2006). Malakula: A Photographic Collection. Comparative Studies in Society and History 48(3):520–563.

Geismar, Haidy and Christopher Morton (2015). Reasserting Presence, Reclamation and Desire. Photographies 8(3):253–270.

Gell, Alfred (1992). The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology. In: Anthropology, Art and Aesthetics. Ed. by J. Coote and A. Shelton. Oxford: Clarendon, 40–66.

– (1998). Art and Agency. An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Ginzburg, Carlo (1993). Microhistory: Two or Three Things That I Know about It. Critical Inquiry 20(1):10–35.

Gumbrecht, Hans Ulrich (2004). Production of Presence: What Meaning Cannot Convey. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Hahn, Hans Peter and Hadas Weiss, eds. (2013). Mobility, Meaning and the Transformations of Things: Shifting Contexts of Material Culture through Time and Space. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Haraway, Donna J. (1991). Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. London: Routledge.

Hevia, James L. (2009). The Photography Complex: Exposing Boxer-Era China (1900 – 1901), Making Civilization. In: Photographies East: The Camera and Its Histories in East and Southeast Asia. Ed. by Rosalind C. Morris. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 79–121.

Hodder, Ian (2012). Entangled. An Archaeology of the Relationships between Humans and Things. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Hoskins, Janet (1998). Biographical Objects: How Things Tell the Stories of People’s Lives. London: Routledge.

Hübner, Gerhild (2004). Zu den Anfängen der Photographie in der deutschsprachigen Klassischen Archäologie. Ihre Anwendung während der ersten zwei Jahrzehnte der Pergamongrabung. Istanbuler Mitteilungen 54:83–111.

Huhtamo, Erkki and Jussi Parikka, eds. (2011). Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications. Oakland: University of California Press.

Kästner, Ursula (2011). ‘Ein Werk, so groß und herrlich ... war der Welt wiedergeschenkt!‘: Geschichte der Ausgrabungen in Pergamon bis 1900. In: Pergamon: Panorama der antiken Metropole. Exhib. cat. Antikensammlung der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin. Petersberg: Imhof, 36–44.

Klamm, Stefanie (2017). Bilder des Vergangenen: Visualisierung in der Arch äologie im 19. Jahrhundert—Fotografie, Zeichnung und Abguss. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag.

Knappett, Carl (2011). An Archaeology of Interaction: Network Perspectives on Material Culture and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kopytoff, Igor (1986). The Cultural Biography of Things: Commodification as Process. In: The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Ed. by Arjun Appadurai. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 64–91.

Krumme, Michael (2008). Der Beginn der archäologischen Fotografie am DAI Athen. In: Διεθνές Συνέδριο Αφιερωμένο στον Wilhelm D örpfeld: υπό την Αιγίδα του Υπουργείου Πολιτισμού, Λευκάδα 6-11 Αυγούστου 2006. Ed. by Chara Papadatou-Giannopoulou. Patra: Peri Technōn, 61–78.

Langford, Marta (2001). Suspended Conversations. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Latour, Bruno (2005). Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lehmann-Brauns, Susanne, Christian Sichau, and Helmuth Trischler, eds. (2010). The Exhibition as Product and Generator of Scholarship. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science.

Maxwell, Richard, Jon Raundalen, and Nina Lager Vestberg, eds. (2015). Media and the Ecological Crisis. London: Routledge.

McCauley, Elisabeth Anne (1994). Industrial Madness: Commercial Photography in Paris, 1848 –1871. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

McQuire, Scott (2013). Photography’s Afterlife: Documentary Images and the Operational Archive. Journal of Material Culture 18(3):223–241.

Miller, Daniel (1987). Material Culture and Mass Consumption. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

– ed. (1998). Material Cultures: Why Some Things Matter. London: UCL Press.

– (2015). Photography in the Age of Snapchat. London: Royal Anthropological Institute.

Miller, Daniel and Jolynna Sinanan (2017). Visualising Facebook. London: UCL Press.

Mirzoeff, Nicolas (2003). The Shadow and the Substance: Photography and Indexicality in American Photography. In: Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self. Ed. by Coco Fusco and Brian Wallis. New York: International Center for Photography / Harry N. Abrams, 111–128.

Mitchell, W. J. T. (1994). Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

– (1996). What Do Pictures “Really” Want? October 77:71–82.

– (2005a). There Are No Visual Media. Journal of Visual Culture 4(2):257–266.

– (2005b). What Do Pictures Want?: The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Mitchell, William J. T. (1992). The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mitman, Gregg and Kelley Wilder, eds. (2016). Documenting the World: Film, Photography, and the Scientific Record. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Olin, Margaret (2012). Touching Photographs. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Pinney, Christopher (1997). Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographs. London: Reaktion Books.

– (2003). Introduction. In: Photography’s Other Histories. Ed. by Christopher Pinney and Nicolas Peterson. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1–16.

– (2004). “Photos of the Gods.” The Printed Image and Political Struggle in India. London: Reaktion Books.

– (2005). Things Happen: Or, From Which Moment Does That Object Come? In: Materiality. Ed. by Daniel Miller. Durham NC: Duke University Press, 256–272.

– (2006). Four Types of Visual Culture. In: Handbook of Material Culture. Ed. by Christopher Tilley, Keane Webb, Susanne Küchler, Mike Rowlands, and Patricia Spyer. London: Sage, 131–144.

– (2008). The Coming of Photography in India. London: British Library.

Pinney, Christopher and Nicolas Peterson, eds. (2003). Photography’s Other Histories. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Poole, Deborah (1997). Vision, Race and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

– (2005). An Excess of Description: Ethnography, Race, and Visual Technologies. Annual Review of Anthropology 34:159–179.

Rose, Gillian (2000). Practising Photography: An Archive, a Study, Some Photographs and a Researcher. Journal of Historical Geography 26:555–571.

– (2010). Doing Family Photography: The Domestic, The Public and The Politics of Sentiment. Farnham: Ashgate.

Rosler, Martha (1989). in, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography). In: The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography. Ed. by Richard Bolton. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 303–341.

Ruchatz, Jens (2012). Kontexte der Präsentation. Zur Materialität und Medialität des fotografischen Bildes. Fotogeschichte 124:19–28.

Sandweiss, Martha A. (2007). Image and Artifact: The Photograph as Evidence in the Digital Age. The Journal of American History 94(1):193–202.

Sassoon, Joanna (2004). Photographic Materiality in the Age of Digital Reproduction. In: Photographs, Objects, Histories. Ed. by Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart. London: Routledge, 186–202.

Schlehe, Judith and Sita Hidayah (2014). Transcultural Ethnography: Reciprocity in Indonesian-German Tandem Research. In: Methodology and Research Practice in Southeast Asian Studies. Ed. by Mikko Huotari, Jürgen Rüland, and Judith Schlehe. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 253–272.

Schneider, Franka (2019). Tandemforschung im Foto-Archiv: Ein Bericht aus dem interdisziplinären Projekt “Foto-Objekte”. In: Zusammen arbeiten: Praktiken der Koordination und Kooperation in kollaborativen Prozessen. Ed. by Stefan Groth and Christian Ritter. Bielefeld: transcript, 135–163.

Schneider, Franka, Julia Bärnighausen, Stefanie Klamm, and Petra Wodtke (2017). Die Materialität des punctum: Zum Potential ko-laborativer Objekt- und Sammlungsanalysen in Foto-Archiven. In: Eine Fotografie: Über die transdisziplinären Möglichkeiten der Bildforschung. Ed. by Irene Ziehe and Ulrich Hägele. Münster: Waxmann, 217–241.

Schwartz, Joan M. (1995). We Make Our Tools and Our Tools Make Us: Lessons from Photographs for the Practice, Politics, and Poetics of Diplomatics. Archivaria: The Journal of the Association of Canadian Archivists 40:40–74.

– (2002). Coming to Terms with Photographs: Descriptive Standards, Linguistic ‘Othering,’ and the Margins of Archivy. Archivaria: The Journal of the Association of Canadian Archivists 54:142–171.

– (2011). The Archival Garden: Photographic Plantings, Interpretive Choices, and Alternative Narratives. In: Controlling the Past: Documenting Society and Institutions. Ed. by Terry Cook. Chicago, IL: Society of American Archivists, 69–110.

– (2012). ‘To Speak Again With a Full Distinct Voice’: Diplomatics, Archives, and Photographs. In: Archivi fotografici: spazi del sapere, luoghi della ricerca. Ed. by Costanza Caraffa and Tiziana Serena. Rome: Carocci Editore, 7–24.

Schwartz, Joan M. and James Ryan, eds. (2003). Picturing Place: Photography and the Geographical Imagination. London: I. B. Tauris.

Sekula, Allan (1982). On the Inventions of Photographic Meaning. In: Thinking Photography. Ed. by Victor Burgin. London: Macmillan, 84–109.

– (1989). The Body and the Archive. In: The Contest of Meaning. Critical Histories of Photography. Ed. by Richard Bolton. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 343–389.

Smith, Shawn Michelle (1999). American Archives: Gender, Race, and Class in Visual Culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Solomon-Godeau, Abigail (1984). Photography after Art Photography: Gender, Genre, History. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Stafford, Barbara M. (1999). Visual Analogy: Consciousness as the Art of Connecting. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Tagg, John (1988). The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photography and Histories. London: Macmillan.

Tucker, Jennifer (2005). Nature Exposed: Photography as Eyewitness in Victorian Science. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

VanDijck, Jose (2007). Mediated Memories in the Digital Age. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Walton, Shireen (2016). Photographic Truth in Motion: The Case of Iranian Photoblogs. London: Royal Anthropological Institute.

Were, Graeme and Paolo Favero, eds. (2013). Imaging Digital Lives: Participation, Politics and Identity in Indigenous, Diaspora, and Marginal Communities. 18(3). Special Issue of Journal of Material Culture.

Winter, Franz, ed. (1908). Altert ümer von Pergamon, Vol. 7,2: Die Skulpturen mit Ausnahme des Altarreliefs. Berlin.

Wright, Christopher (2013). The Echo of Things: The Lives of Photographs in the Solomon Islands. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Footnotes

The DAI (now the German Archaeological Institute’s Istanbul Section, established in 1929) still remains responsible for the excavations of Pergamon. I am very grateful to Stefanie Klamm, Martin Maischberger, and Petra Wodtke for their advice and valuable suggestions while I was writing this paragraph.

The “Red Basilica” was recently restored and reconstructed, with the reinstallation of, inter alia, pieces such as the torso from our photograph.

See also Conze 1902, 6.

http://photothek.khi.fi.it/documents/oau/00000303?Language=en, accessed August 14, 2019.

https://www.khi.fi.it/pdf/veranstaltungen/20170215_photo-objects.pdf, accessed August 14, 2019.

See the complete program of the conference on https://www.khi.fi.it/pdf/veranstaltungen/20170215_photo-objects.pdf, accessed August 14, 2019.

Similarly influential was actor-network theory, which is also discussed later in this essay.

In such seminal publications as Schwartz and Ryan 2003; Pinney and Peterson 2003; Edwards and Hart 2004.

See also Edwards 2012; Ruchatz 2012.

See Dennis 2009.

On the prevalence of literary and linguistic methods and theories aimed at ‘reading’ photographic images like a text, see Baetens 2007.

On visual studies from the standpoint of material culture studies, see Pinney 2006.

Further interesting methodological tools came in the meantime from remediation theory (Bolter and Grusin 1999) and media archaeology (Huhtamo and Parikka 2011).

Described in detail by Petra Wodtke in the collaborative essay of Bärnighausen et al. in this publication (Chapter 2).

See also Caraffa 2017.

See also Favero 2013.

On the concept of presence, although not referred to photography, see also Gumbrecht 2004.

https://www.khi.fi.it/en/photothek/florence-declaration.php, accessed August 14, 2019.

See also Sassoon 2004 and Sandweiss 2007.

See, inter alia, Langford 2001; Pinney 2004; Edwards 2005; Edwards 2009; Campt 2012; Wright 2013.

See Schlehe and Hidayah 2014; Schneider et al. 2017; Schneider 2019 for further literature on tandem research and collaborative anthropology.

See Schwartz 1995; 2002; 2011; 2012.

Among the outputs of the projects I should also mention Bärnighausen et al. forthcoming, with a chapter dedicated to the making of our exhibition.