The photographs of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881–1938), the founder of the Turkish Republic (1923), have remained in circulation after his death in 1938 all through the republican history to this day. The press plays its part in this by publishing various Atatürk photographs from time to time, mostly on special occasions. Labels such as “the photographs never seen before” or “photographs recently taken out of the archives” frequently accompany these pictures in the newspapers. Upon closer inspection, however, it becomes evident that most of them, allegedly brought to light for the very first time, were actually printed and distributed in various forms before. The archives these pictures were taken from remain ambiguous; their names are rarely mentioned. Thus, the archive turns into a big, abstract entity that is virtually impenetrable. This paper will focus upon my experience of conducting research on Atatürk photographs in Turkish archives and discuss the contrast between the emphasis placed on the archive and what this archive actually means when it is kept away from you.

5.1 Invisible photographs

The Atatürk photographs first entered into circulation in the press in 1912 when Mustafa Kemal Atatürk was an Ottoman military commander. They continued to be published from time to time in the coming years along with news concerning his military duty in the Ottoman army. The number and variety of his photographs increased throughout the Turkish War (1919–1922), during which he gradually became the leader of the resistance movement, known as the National Forces, revolting against the occupation of the Allied Powers after World War I. Although the National Forces claimed to protect the nation and the state as well as the Ottoman dynasty and the caliphate throughout the Independence War (Şeker 2009, 1169), once the war ended with the victory of the National Forces, there came about a change in the regime: the dynasty and the caliphate were abolished and the new Turkish state, a republic, was declared. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk became the head of this new regime as a result of the legitimacy he gained as the leader of the Independence War, and remained in this role until he passed away in 1938.

The establishment of a new state required breaking ties with the Ottoman Empire. During the fifteen years he served as the president of the country as well as with the cadres of the period, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk determined the path that the new country should follow. This path was achieved through various reforms, as a result of which the country underwent a radical transformation affecting everything from its judicial system to its educational system, social life, fashion, and alphabet. The press was an important medium for helping the people become accustomed to the reforms. Newspapers and magazines made great use of photographs for this purpose, which were meant to display the changing face of the country and to compare the old, which was propagated as “bad,” and the new, which was considered “good.” The photographs of Atatürk were also very prominent during these years. Like the press, they, too, helped familiarize the citizens with the radical transformations the country was undergoing, as they showed the leader introducing or performing the reforms himself.

The photographs of Atatürk also served to show the leader of the country, the man who “saved the country and set it free” and who was now “modernizing it,” on a daily basis. The time in which these photographs were first taken and circulated in the republican era was a period when mass politics backed up with a leader cult were very prominent in many countries. Systems where the country was under the rule of a single party and a “classless society” converging around the leader of this party emerged after World War I not only in Italy, Germany, and the USSR, but also in Romania, Poland, Hungary, Portugal, and Spain, among others (Arendt 1958, 309). All of these states made great use of visual media in order to differentiate themselves from the systems left behind and to display what the new regime represented. This involved a visual regime around the leader cult where the visibility of the leader, among other symbols, was of utmost importance.

Although early republican Turkey was similar in this sense, there were differences in certain aspects. For example, when it comes to the photographs of Atatürk, for a very long time, maintaining this visibility was not a deliberate undertaking of the state. There was never an institution specializing in this area. His photographs were taken mainly by photojournalists and were circulated in the press. They were edited, if necessary, by the editors of the newspapers and not by any government officials. But what might be effectively different with Turkey (a country which, unlike those mentioned above, did not undergo a further change of regime) is that this visuality in general and the photographs of Atatürk in particular have remained in circulation to this day. This circulation was enabled by legislation in some cases, as the textbooks used in schools are still supposed to have his picture on the very first page and the state institutions are required to hang up portraits of him. Pictures of Atatürk are also still very prominent during national holidays. Exhibitions of his photographs are organized from time to time as well as numerous albums containing Atatürk’s photographs, with the latest ones being published continuously. The press also plays its part in this circulation, as photographs of Atatürk continue to be published particularly on special occasions such as national holidays and anniversaries of other major events.

The circulation of these photographs throughout the republican history has certainly had its ups and downs. We witness a rise in Atatürk symbolism at times when the state ideology, Kemalism, derived from the name of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, was believed to be at stake. Therefore, the Islamist and Kurdish movements in the 1990s, for example, two movements that oppose the secular and nationalist foundations of the state, brought a rise in Atatürk symbolism in their wake (Bozdoğan and Kasaba 1997, 3–14). The coming to power of the Justice and Development Party of Turkey (AKP) in 2002 also triggered this tendency. Photographs of Atatürk became widespread again; those who embraced the Kemalist ideology showed their discontent with the current government by turning back to Atatürk.

As an undergraduate student, I was intrigued by the rise in this symbolism back then, that is, how these photographs, which were taken eighty to ninety years previously, could still be very much contemporary for many people. This curiosity then evolved into a dissertation topic when I started my PhD in Political Science. My aim was to look at what these photographs meant in the present and what kinds of affiliations and ways of remembering the past they represented for Turkish citizens at the time. My original intention was to carry out interviews using photo-elicitation, that is, showing a pile of photographs to my interviewees in order to see how they responded to them. However, I gave up on this plan during the pilot interviews in 2013, when I realized that the people I was speaking to responded to these photographs from within the current political framework. What they saw in these pictures, depending on their relationship with Kemalism and Atatürk, was either the “good deeds” or the “bad deeds” of today. This would be a perfectly legitimate dissertation topic: looking at what kinds of approaches these photographs from the past offered for our present political understanding. But I realized that this would be more an analysis of the current political situation and not of the photographs themselves.

While I was preparing for the interviews, I was already looking at how these photographs were originally published. As mentioned above, the majority of Atatürk photographs were taken by photojournalists of his time and then printed in newspapers and magazines. Hence, during this initial phase, I was going through all the newspapers and magazines of the early republican period because I wanted to see the difference between what they were meant to show originally and what they later came to mean. It was during this period that I became aware that there had never been any research on these photographs throughout the entire republican history. Work has been done on the status of Atatürk and on how his image was incorporated into objects such as T-shirts, mugs, and crystal spheres. There is even a study on tattoos depicting Atatürk images or his signature.1 But there was never any research on his photographs. It was very strange to realize how these photographs, which could be seen all around us, were somehow “invisible” in the sense that they had never been analyzed before. Consequently, I decided to take a closer look at them during the period in which they were first taken and circulated and to explore the visual regime of the early republican period with its foundations built around the visibility of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

5.2 Photographs recently taken out of the archives

The fact that there has never been any research conducted on the photographs of Atatürk seems even more incredible since there is a constant interest in them. As stated earlier, exhibitions, albums, and newspapers continue to show and circulate these photographs. In addition, online journalism gives rise to the opportunity of publishing hundreds of photographs at once, which could not have been done in printed newspapers.

When these photographs are circulated today, it is very common to hear or read phrases such as “photographs never seen before” or “photographs recently taken out of the archives.” However, when we look at these pictures, it is possible to see that they were in fact circulated previously. For example, Habertürk, a Turkish news agency, published many photographs of Atatürk in 2013 with the heading “The Last Photographs of Atatürk!” (Atatürk’ün Son Fotoğrafları!) (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk on the Front During National Independence War, published on the website of Habertürk news agency as “The Last Photographs of Atatürk.”

It is stated in the explanation that the Atatürk Research Center of the Atatürk Supreme Council for Culture, Language and History (ATAM) had brought very special photographs of Atatürk to daylight for the national holiday on May 19, which is the Commemoration of Atatürk, Youth and Sports Day. One of the photographs published there, displaying Atatürk on the front during the Independence War, was in fact widely circulated earlier, for example, in a photographic book from 2006 (Akşit 2006, 89) (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk on the Front During National Independence War, published in Akşit, İlhan: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Akşit Yayınları, İstanbul 2006, p. 89.

Another example can be seen on the website of Sabah newspaper, where three hundred “least known” photographs of Atatürk were published in 2014 (Atatürk’ün Çok Az Bilinen 300 Fotoğrafı). One of the photographs there was in fact part of another very famous photographic book in 2009 (Benazus 2009, 240) (see Figs. 3–4).

Fig. 3: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk Drinking Coffee, published online on the website of Sabah newspaper, November 10, 2008.

Fig. 4: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk Drinking Coffee, published in Benazus, Hanri: Çağdaş Atatürk Fotoğrafları [Contemporary Photographs of Atatürk], vol. 1, Tudem Yayınevi, İstanbul 2009, p. 240.

The same photograph can be seen in the 1972 Milliyet newspaper in an article entitled “The Photographs of Atatürk Never Published Before” (Atatürk’ün Hiçbir Yerde Yayımlanmamış Fotoğrafları) (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk Drinking Coffee and Atatürk’s Portrait, published in Milliyet, November 13, 1972, p. 7.

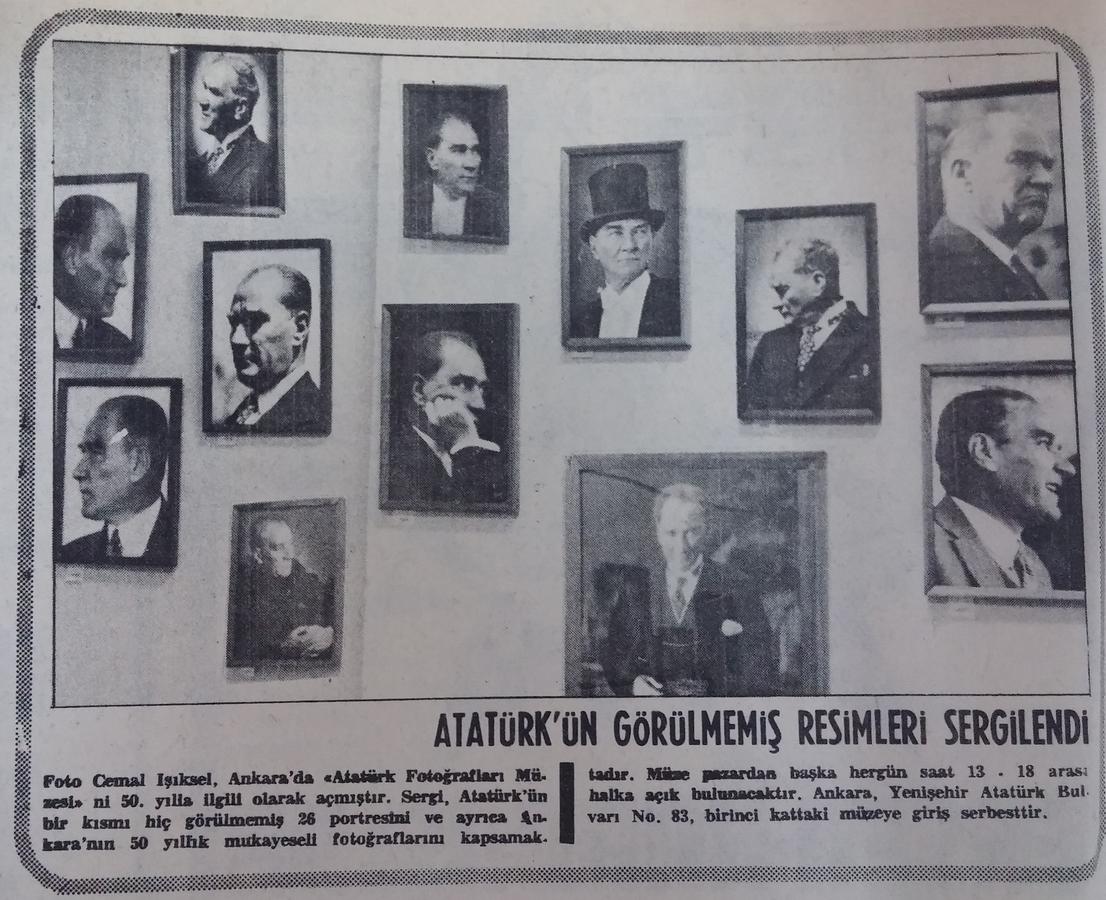

The second photograph on this page, which is also allegedly brought to daylight for the very first time, can be traced back to a series of a portraits from an exhibition where “the unseen pictures of Atatürk were exhibited” in 1973 (Atatürk’ün Görülmemiş Resimleri Sergilendi) (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Atatürk’s Portrait, published in Milliyet, October 27, 1973, p. 5.

These are just a few examples of a phenomenon which was prevalent throughout the republican history; that is, bringing out the photographs of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk over and over again while claiming to display them for the very first time and, thus, attempting to present Atatürk as new, contemporary, and relevant for all ages. What is common to most of these examples is that the names of the archives from which these photographs were taken are rarely mentioned. This ambiguity surrounding the specific archive turns it into an indefinite structure that appears inaccessible at times.

The contrast between the emphasis placed on the fact that these photographs were taken from archives and the indifference to the specific archives themselves, which manifests itself in the failure to mention their names, initially escaped my attention. I only became aware of this issue when I went to the archive by myself, not to look for any particular photograph, but for what was written about these photographs. My dissertation also involves the decisions made by early republican state officials concerning the question of who is able to disseminate these photographs in which media and when. Consequently, I went to the Directorate of Republican Archives of the Prime Ministry to find out more about these decisions. During my time there, I began to come across files that were about specific photographs but did not include the pictures in question. For example, there was one file about a crisis that occurred in 1935: a magazine called La Turquie Moderne published a photograph of Atatürk, which triggered an exchange of letters with the state departments claiming that this was a fake photograph of Atatürk and that the magazine had to be punished for circulating it.2 The file in the archive contains many documents, most of which say that the photograph in question or the periodical in question could be found in the attachment, but none of them were in the file. Another file about the operations of an electricity company in the early republican period contained both photographs of the facility and of Atatürk.3 Although the connections between these different photographs were not clear at first, I later found out that Atatürk happened to visit the company in the past and that photographs from this visit were deemed appropriate to be added to a file about the operations of this facility.

This was the first time I became aware of the question of how these photographs were stored in the archives. The sentence “the photographs recently taken out of the archives” was so natural for me that it took me some time to realize that I had not seen as many Atatürk photographs as I should have in this archive. In fact, I came across only two pictures in a file where I least expected to find them. This is how the issue of the archive became a matter of curiosity to me and I began to visit various institutions to look for the photographs of Atatürk. My aim was not to find new photographs, ones that had “never been seen before.” I was just curious about how the photographs were stored.

Once I was at the Directorate of Republican Archives of the Prime Ministry in Ankara, I began to search for the photographs of Atatürk. The archive does not have a separate photography section, but there are many files on the photographs of Atatürk. His photographs were sent to various institutions all around to country to be hung up from 1935 onward. There are hundreds of files about this matter. Some also concern photographs donated to institutions and individuals when requested. There are even more files about how to hang up his portraits in state institutions. But none of the files contain any actual photographs of Atatürk. Apart from the one file about the operations of the electricity company, it was not possible to find a single photograph of Atatürk in this archive.

One of the archives I decided to go was the Presidential Archive, which is currently located within the Presidential Palace in Istanbul. The issue with this archive is that it is not possible to access it. If you need to consult this archive, you have to fill in a form with information on what is required from the archive and why. The form is then sent to the General Secretariat of the Presidential Office. After a while, you receive a CD with the materials deemed relevant to what is stated in the form. Therefore, it is not possible to search for materials personally nor to see the complete collections or the storage situation. Instead, you are given a pile of files containing photographs that could be found in any Atatürk photo book.

Another archive that did not allow me to go through the materials was the archive of the Directorate General of Press and Information, in Ankara. When I made a formal application to receive permission to enter the archive, I was initially told that it could not be consulted by individuals, only by institutions. However, I was later told that they were willing to help me because my research was about Atatürk. Despite their good will, I was still not allowed to go into the archive by myself. Instead, I was given the web address of the Anatolian News Agency, a Turkish news agency owned by the state. Normally, Anatolian News Agencies use this website to sell photographs taken by registered photojournalists. I was told that there were many pictures of Atatürk on the website. I could take a look at them, choose a maximum of twenty, and then they would give them to me for free.

Yet another archive I went to belonged to the Turkish History Society, also in Ankara. This institution was founded in 1931 by Atatürk himself in order to carry out research on Turkish history. When I was granted permission to see the archive, I was initially asked to go through the list of all the digitized materials and to choose which I would like to see. The problem with this list was that it did not include much information about the photos. It contained only the titles given to the photographs by archivists and sometimes the titles were as short as “Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.” Going through this list, I had to draw up my own list of the materials I wanted to see by looking at their titles only. My personal list was then transferred to the archive employees who were then required to sort all the materials mentioned one by one. I later discovered, during an informal conversation over a tea break with some of the employees, that there were also a couple of glass plates of Atatürk, but these were not cataloged. They promised to show them to me one day but could not do so immediately because, they told me, it was “hard to find them.”

The final archive I visited was that of the National Library in Istanbul which used to have a section called the Atatürk Archive. This was a separate room full of documents, photographs, postcards, stamps, and books about Atatürk. All the documents were stored in unclassified or uncataloged files or boxes, which made it very difficult to go through them without knowing, for example, what year they were dated. The location of this archive changed recently. A new small room was constructed on the top floor, like a showcase. There is still a sign saying “Atatürk Archive” on the door, but it now contains only books about Atatürk. All the visual materials had been transferred, I was told, to the non-book materials section of the library. When I applied to go through the photographs, it turned out that all the materials were still uncataloged and scattered. Although the employees there were willing to show them to me, it was hard to locate the files. In the end, I was able to see only four photographs and around fifty postcards.

5.3 Fear of archives

This was my overall experience in the five state archives. There are a few reasons why I encountered these difficulties in terms of finding photographs. One is related to the general problem of archive keeping in Turkey. Part of this general problem is related to the fear, on the part of the state, that something inconvenient might be found in the archives, which results in strict censorship. Therefore, most of the time, users are not allowed to consult the archives by themselves or they can access only a very small fraction of the materials. Moreover, the recent digitization of many archives caused a second process of censorship, as all the materials were checked once again while being digitized. One becomes aware of this censorship only when a document previously seen in the archive can no longer be found in the catalog. Another part of the general problem with archive keeping in Turkey is related to a kind of oblivion, a willful oblivion even, toward the documents of the past. This willful oblivion can be traced back to the early republican period, that is, to a time when the ties with the old regime were being broken and the documents of the past were therefore destroyed, went to waste, or were left somewhere to rot. The same can be seen happening over and over again throughout the entire republican history. In his book on the Turkish archives, The Story of a Slaughter, a Raid, Rıfat Bali analyzes the archives of various state institutions in Turkey and describes what happened to each of the individual documents, such as archival materials sent to the SEKA paper factory or sold to waste collectors (Bali 2014).

This also applies to the documents about Atatürk: there is a fear that something inconvenient might be found, which would jeopardize the image of Atatürk. A law regarding crimes against Atatürk, enacted in 1951 and still in effect to this day, shows how protecting the image of Atatürk is still very important (Atatürk Aleyhinde İşlenen Suçlar Hakkında Kanun).4 Consequently, strict censorship is applied to documents related to him in the archives. Although it is more difficult to prove this same process when it comes to Atatürk because he is still such an important figure in Turkey, we know of at least one example where a document of Atatürk was found in a garbage disposal. Atilla Oral, a journalist from Turkey, wrote a book about a letter Atatürk sent to the Turkish History Society and criticized this society, which Atatürk himself established to carry out research on Turkish history, distorted this history and did not write about it objectively (Oral 2011). Atilla Oral describes how this letter was thrown into the garbage from the archives of Turkish History Society and calls it an act of censorship. It is possible to interpret this as willful oblivion as well, since the documents that did not fit the image built around Atatürk were deliberately lost. But it is not possible to have an accurate idea about the scale and frequency of this situation, as we do not know whether there are other cases in which documents about Atatürk were destroyed or almost destroyed.

Apart from this general problem with archive keeping in Turkey, another particular difficulty I faced was that I was looking for photographs of Atatürk. Photography is still not a very common research object or subject in Turkey. It mostly remains within the confines of fine arts departments and there is only a small number of researchers who focus on the history of photography or who approach photographs from a socio-scientific perspective. This means that photographs are not treated as important documents in the archives. Some archives do not have a photography section—so coming across a photograph can be quite accidental. Even in cases where there is a photography section, the number of photographs, which are already very poorly cataloged or classified, can be very limited.

I must say that in all the archives I went to, I was only able to see what I saw because of the helpfulness of the people working there. But no matter how willing they were to help, there was an institutional or formal attitude which predetermined their ability to do so. The fear of the archive and the tradition of willful oblivion affect the institutional framework, which in turn posits a barrier that is difficult to overcome. Allan Sekula refers to the archive as a “territory of images” (Sekula 2002, 444). In my case, however, this is not a “territory” that you are allowed to enter on your own or walk around in freely. The archive, in my experience, is not a place to begin investigating either. Rather, it is somewhere to go at a later stage of research in order to be able to compare what you already know and what you are allowed to see.

The archive, in my case, did not contribute to a better understanding of or a fruitful confusion about a research subject, there is no way to just “let the photos talk.” Instead, it provides insights into how the state perceives and approaches this subject matter, which is ultimately also a part of the photograph’s history—if it is possible to identify and permeate those processes. The limited number of materials that are accessible in the archives, if any, together with the fact that, in most cases, you cannot choose the materials you need to see yourself, makes it very difficult to give new meaning to historical events or personalities. Rather, the archive provides an image of what kind of meaning is attached to these events or personalities by the state authorities. This was why I was told in one of the archives that this archive could not be used by individuals but only by institutions. An institution, especially a state institution, would know how to handle the material and what not to use in order not to jeopardize any meaning previously attached. On the other hand, individuals, they believe, always carry the risk of going against the established meanings. Therefore, the archive, in my experience, does not represent a place where a researcher can ascribe new meanings to the past; instead, it stands for what should be kept and protected as it is. Aleida Assmann says about the archive that the materials to be found there are “stored and potentially available, but … not interpreted,” as a result of which the archive becomes “a space that is located on the border between forgetting and remembering” (Assmann 2011, 336). In my personal archival experience, however, the limited number of materials available to study, the difficulty in accessing these materials, and the institutional or formal attitude which predetermines what can be seen and what can be done means that the archive is not a place where anyone can freely interpret the materials that have not yet been interpreted, but rather somewhere to rehearse the meanings already attached.

Early in the present paper, I said that the names of the archives from which the allegedly “new” photographs were taken are rarely mentioned. Consequently, the archive turns into a big abstract entity that is impenetrable. Although the archive is very much there, as an institution, with its door, and desks and files, the fear of the archive and the tradition of willful oblivion predetermines what can be seen and what can be done. It should also be noted, however, that although the state of these archives works as a barrier to accessing information, the researcher is in no way powerless against the “naturalization” of what the archive is to offer (Schwartz and Cook 2002, 3). The inability to access information inescapably draws the critical gaze towards the archive. The failure to encounter archival materials leads us to question the very structures of the archives and the objectivity attributed to them and, hence, to give back to the archive some of the specificity they attempted to erase.

5.4 List of Figures

• Fig. 1: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk on the Front During National Independence War, published on the website of Habertürk news agency as “The Last Photographs of Atatürk!,” May 18, 2013, https://www.haberturk.com/galeri/gundem/427757-arsivden-cikan-ataturk-fotograflari/1/69, accessed February 5, 2017.

• Fig. 2: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk on the Front During National Independence War, published in Akşit, İlhan: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Akşit Yayınları, İstanbul 2006, p. 89.

• Fig. 3: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk Drinking Coffee, published on the website of Sabah newspaper as “The Least Unknown 300 Photographs of Atatürk,” Sabah, https://www.sabah.com.tr/galeri/turkiye/ataturkun_cok_az_bilinen_300_fotografi/129, accessed December 1, 2015.

• Fig. 4: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk Drinking Coffee, published in Benazus, Hanri: Çağdaş Atatürk Fotoğrafları [Contemporary Photographs of Atatürk], vol. 1, Tudem Yayınevi, İstanbul 2009, p. 240.

• Fig. 5: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Drinking Coffee, published in “Atatürk’ün Hiçbir Yerde Yayımlanmamış Fotoğrafları” [The Photographs of Atatürk Never Published Before], Milliyet, November 13, 1972, p. 7

• Fig. 6: Atatürk’s Portrait, published in “Atatürk’ün Görülmemiş Resimleri Sergilendi” [The Unseen Pictures of Atatürk Were Exhibited], Milliyet, October 27, 1973, p. 5.

5.5 References

Şeker, Nesim (2009). İmge, Bellek ve Tarih: Milli Mücadele Dönemi [Image, Memory and History: National Struggle Period]. In: Modern T ürkiye’de Siyasi D üşü nce. Vol. 9: Dönemler ve Zihniyetler. Ed. by Tanıl Bora and Murat Gültekin. İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 1163–1194.

Akşit, İlhan (2006). Mustafa Kemal Atat ürk. İstanbul: Akşit Yayınları.

Arendt, Hannah (1958). The Origins of Totalitarianism. Cleveland and New York: Meridian Books.

Assmann, Aledia (2011). Canon and Archive. In: The Collective Memory Reader. Ed. by Jefrrey K. Olick et al. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 334–337.

Bali, Rıfat (2014). Bir Kıyımın, Bir Talanın Öyküsü [The Story of a Slaughter, of a Raid]. İstanbul: Libra Kitabevi.

Benazus, Hanri (2009). Ç ağdaş Atat ürk Fotoğrafları [Contemporary Photographs of Atatürk]. Vol. 1. İstanbul: Tudem Yayınevi.

Bozdoğan, Sibel and Reşat Kasaba, eds. (1997). Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press.

Erim, Bilun (2011). Making The Secular Through The Body: Tattooing the Father Turk. MA thesis. Middle East Technical University.

Oral, Atilla (2011). Atat ürk’ü n Sansürlenen Mektubu [The Censured Letter of Atatürk], İstanbul: Demkar Yayınevi.

Özyürek, Esra (2004). Miniaturizing Atatürk: Privatization of State Imagery and Ideology in Turkey. Ethnologist 31(3):374–391.

Schwartz, Joan M. and Terry Cook (March 2002). Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory. Archival Science 2(1):1–19. issn: 1573-7519. doi: 10.1007/BF02435628. url: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435628 (visited on August 17, 2019).

Sekula, Allan (2002). Reading an Archive. In: The Photography Reader. Ed. by Liz Wells. London and New York: Routledge, 443–452.

Tekiner, Aylin (2010). Atat ürk Heykelleri: Kült, Estetik, Siyaset [Ataturk Statues: Cult, Aesthetics, Politics]. Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları.

Footnotes

For examples of this research, see Tekiner 2010; Özyürek 2004; Erim 2011.

The Directorate of Republican Archives of the Prime Ministry, Ankara, 30-18-1 / 59-85-9.

The Directorate of Republican Archives of the Prime Ministry, Ankara, 230-0-0 / 12-48-1.

“Atatürk Aleyhinde İşlenen Suçlar Hakkında Kanun” [Law on Crimes Against Atatürk], Resmi Gazete, July 25, 1952, 3:32, p. 1842.