Royal Society

At the time Cavendish entered the Royal Society

Beginning in 1753, candidates for membership had to be known “personally” to their recommenders. Throughout his fifty years in the Society, Cavendish recommended a new member every year or two

A further indication of the continuity of his years in Cambridge is the list of guests he brought to the Royal Society Club

For further information about Cavendish’s associations we return to the book of certificates recommending candidates for fellowship in the Royal Society. His recommendations reflected his current scientific activities. After his first recommendations of candidates from Cambridge mentioned above, his next, in 1769, was of Timothy Lane

Of the almost one hundred fellows of the Royal Society who joined Cavendish in recommending candidates, only a few appear with him on more than one certificate. Nevil Maskelyne appears on half of the certificates, and after him, in decreasing frequency, come the keeper of the natural history department of the British Museum Daniel Solander

In 1765 Cavendish was elected to the Council of the Royal Society

| W. Musgrave |

22 years |

| N. Maskelyne |

20 years |

| H. Cavendish | 17 years |

| Lord Mulgrave |

14 years |

For 1801–1820, the years are:

| C. Blagden |

19 years |

| Lord Morton |

18 years |

| N. Maskelyne | 11years |

| H. Cavendish | 10 years |

Cavendish died in 1810, halfway through the second span. If we look at the last twenty-five full years of Cavendish’s life, 1785–1809, we find that Cavendish’s record was unsurpassed: he served on the Council every one of those years.

We have an idea of the scientific company Cavendish kept on the Council: it is estimated that the average number of scientifically active members on the Council over the twenty years 1761–1781 was between nine and ten, and over the next twenty years 1781 to 1800 it was under seven. Because the activities of the Royal Society constituted a substantial part of Cavendish’s working life, we should have an idea of what that work consisted of. We begin with his first year on the Council, dating from the end of 1765, when he took his oath along with other new members. The year’s activity started with a courtesy related to the “Royal” in the name Royal Society

We look ahead. Cavendish was extensively engaged in two major projects initiated by the Society during his time, the one just mentioned, observations of the transit of Venus in 1769, the second an experiment on the attraction of mountains in 1774. He drew up plans for a voyage of discovery to the Arctic; he worked on changes in the statutes of the Society

Like his father, Cavendish served regularly on the committee of papers,

Following Cavendish’s report in 1766, the Council undertook painstaking preparations for observing the transit of Venus

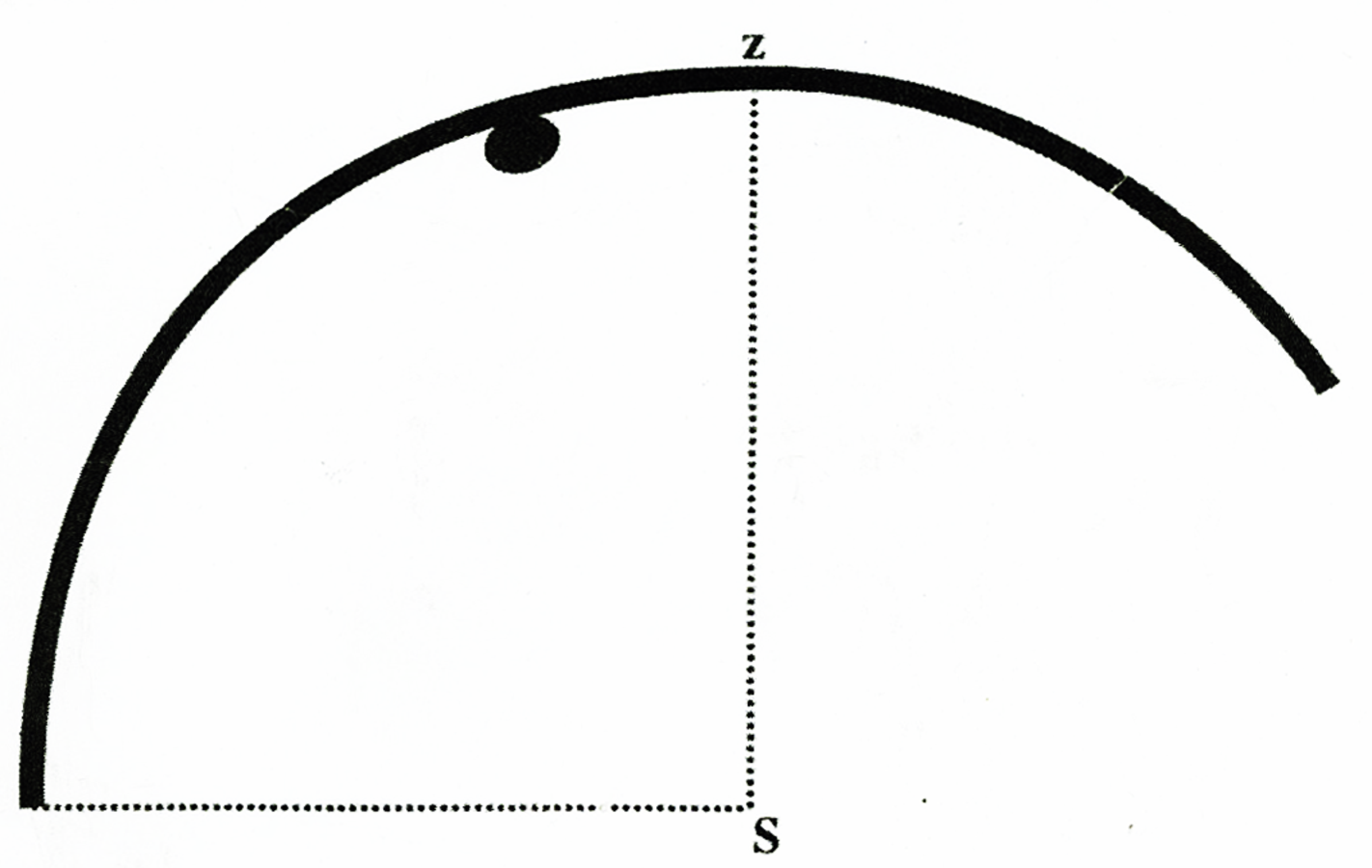

Fig. 10.1: Transit of Venus. On the Island of Maggeroe, on the North Cape of Europe, the transit of Venus of 1769 was observed by William Bailey, who was sent there by the Royal Society. The event was partly obscured by clouds but not completely, as shown by his drawing (which has been redrawn for this book). “Astronomical Observations Made at the North Cape, for the Royal Society,” Philosophical Transactions 59 (1769): 262–66, on 266.

Cavendish studied the observations of the earlier transit of Venus of 1761 at a time when he was carrying out chemical experiments on air. There was a connection of sorts. During the first transit, the effect of the air of Venus was not considered, with the result that the reported times of contact of Venus and the Sun were discordant.19 By making different assumptions about the elastic fluid constituting the atmosphere of Venus, Cavendish computed the errors of observation owing to the refraction of light passing through it from the Sun to the observers on Earth.20 Before Cavendish was done with his work on the transit of Venus of 1769, he had written over 150 pages.21 As it turned out, the observations of the second transit did not result in an unambiguous figure for the distance of the Sun, but the accuracy of the estimate was markedly improved, and the project could be counted as a respectable achievement of measuring science.

In a letter in 1771 from Maskelyne

While at St. Helena to observe the transit of Venus in 1761, Maskelyne made an experiment with a pendulum clock to compare the force of gravity there with that at the observatory at Greenwich. He drew no conclusions from the comparison about the figure of the Earth or the law of change in the force of gravity with latitude, since there was reason to think that the Earth is not homogeneous, in which case the force of gravity depends not only on the external figure of the Earth but also on its internal constitution and density. In a paper written as a letter to Charles Cavendish, Maskelyne said that other kinds of experiments than those with pendulum clocks would have to be made to “be able to infer any thing with certainty, concerning the internal constitution of the Earth, or even to determine its external figure.”23 For the same reason, Henry Cavendish told Maskelyne that the attraction of a mountain was preferable to a pendulum clock for determining the average density of the Earth, being less affected by any inhomogeneity.24 A few years earlier, Cavendish had been concerned with the deviation of a plumb line by the attraction of mountains in connection with errors in measuring degrees of latitude, and he calculated errors for a number of hilly places around the world, including the Allegheny Mountains.25 He gave his paper on rules for computing such errors to Maskelyne who made use of it in a publication in 1768 about Charles Mason

The Royal Society’s experiment had a history. In 1738 French observers measured the deflection of a plumb line on a mountain in South America. They made use of two stations, one on one side of the mountain, and one on the other side several miles away on the same latitude, sufficiently removed from the gravity of the mountain. The same star was viewed from both stations, directly overhead as determined by a plumb line at the distant station and forming a small angle with a plumb line at the other station owing to the attraction of the mountain. The measurements were found to be inexact, and the French hoped that other observers would succeed on a better mountain.

In the middle of 1772, Maskelyne proposed to the Royal Society

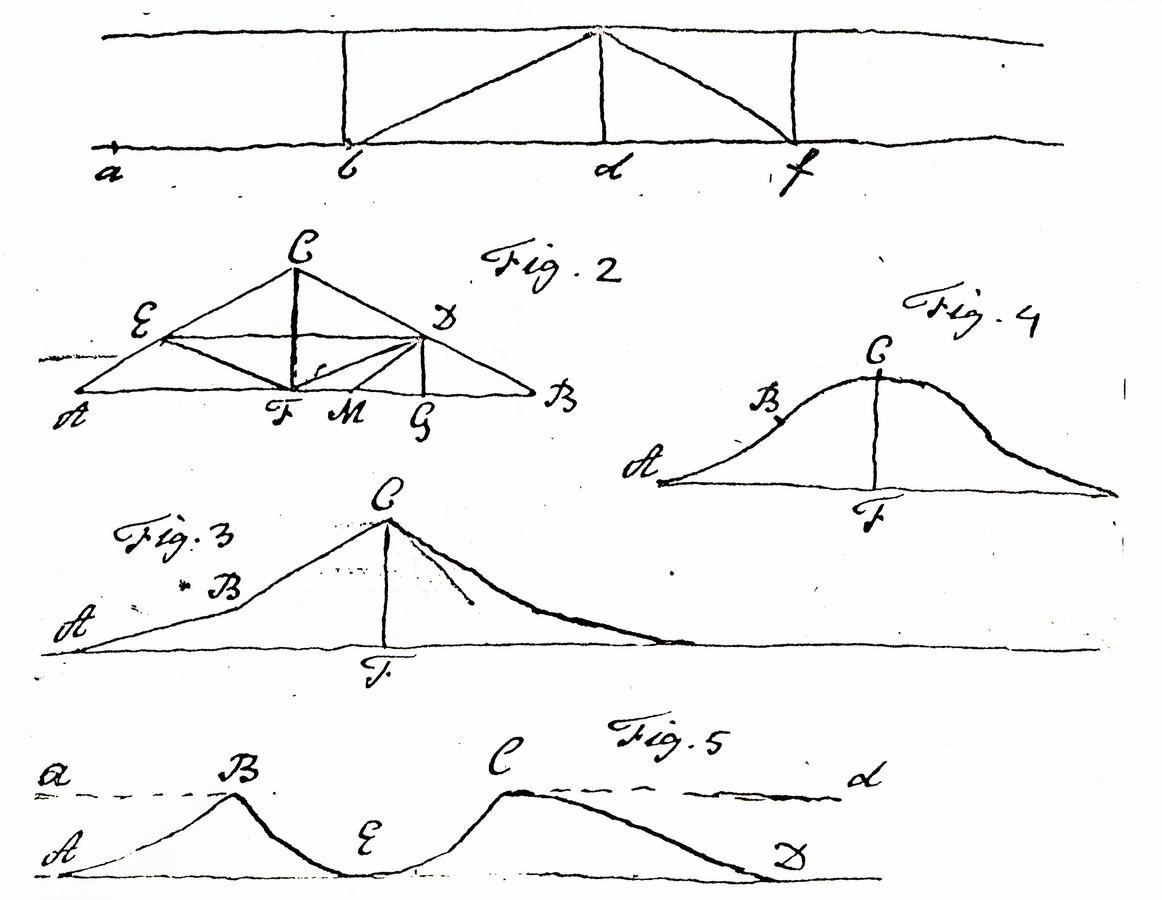

Fig. 10.2: Cavendish’s Drawings of Mountains. For the experiment by the Royal Society to measure the gravitational attraction of a mountain as a means for determining the average density of the Earth, Cavendish drew up rules for selecting the mountain for the purpose. He considered a number of shapes. “Mr.Cavendish’s Rules for Computing the Attraction of Mountains on Plumblines,” Cavendish Scientific Manuscripts VI (b), 2. Courtesy of the Chatsworth Settlement Trustees.

Fig. 10.3: Schehallien. Photograph of the mountain showing its advantageous geometry for determining the average density of the Earth. Wikimedia Commons.

The meridian distance between the north and south observation stations was measured

On the basis of the experiment and Newton’s , he deduced that the “mean density of the whole earth is about

, he deduced that the “mean density of the whole earth is about

the density of water.” Newton’s best guess was that the density of the Earth is between 5 and 6 (“so much justice was even in the surmises of this wonderful man!“). Reminding his readers that this experiment was the first of its kind, Hutton hoped that it would be repeated in other places.35

the density of water.” Newton’s best guess was that the density of the Earth is between 5 and 6 (“so much justice was even in the surmises of this wonderful man!“). Reminding his readers that this experiment was the first of its kind, Hutton hoped that it would be repeated in other places.35

The experiment on the mountain and the Society’s recent concern with the transit of Venus had a common goal: the distance of the Earth from the Sun and the density of the Earth were both standard measures of the solar system

Knowing then the mean density of the Earth in comparison with water, and the densities of all the planets relatively to the Earth, we can now assign the proportions of the densities of all of them as compared to water, after the manner of a common table of specific gravities. And the numbers expressing their relative densities, in respect of water, will be as below, supposing the densities of the planets, as compared to each other, to be as laid down in Mr. de la Lande’s astronomy.

| Water | 1 |

| The Sun |  |

| Mercury |  |

| Venus |  |

| The Earth |  |

| Mars |  |

| The Moon |  |

| Jupiter |  |

| Saturn |  |

Tab. 10.1: Densities of the Solar System

Tab. 10.1: Densities of the Solar System

Thus then we have brought to a conclusion the computation of this important experiment, and, it is hoped, with no inconsiderable degree of accuracy.36

There is a legend that Maskelyne threw a bacchanalian feast for the inhabitants of the region near Schehallien.37 It is hard to picture the proper Maskelyne taking part in this affair and impossible to picture Cavendish, but Cavendish was not there. Just as he did not travel to observe the transit of Venus, he did not go to Scotland to observe stars from a mountain; he planned the experiment from his study on Great Marlborough Street in London.

Around the time of Phipps’s journey, there was keen interest in the Royal Society in the far north. During the transit of Venus

Beginning in 1773, if not earlier, Cavendish incorporated the Hudson’s Bay Company into his network of sources, its northern remoteness affording an opportunity to study nature in a frozen state. In December of that year, as an acknowledgment of its “considerable and repeated benefaction’s,” the Council of the Royal Society moved to send the Company a collection of meteorological instruments with instructions for its officers to measure the weather and report back to the Society, the secretary of the Society Maty

One of Cavendish’s close colleagues in the Royal Society was a professional voyager, the first hydrographer for the East India Company and later the first hydrographer for the admiralty, Alexander Dalrymple

Voyagers held a special interest for Cavendish, who invited them as his guest at the Royal Society and the Royal Society Club. In the certificates book of the Society

Fig. 10.4: Royal Society. Painting by Frederick William Fairholt, engraving by H. Melville. This is the meeting room of the Royal Society at Somerset House 1780–1857. Over the last thirty years of his life, Cavendish came regularly to meetings here. The president of the Society is at the center, and the two secretaries at either side. The paintings on the wall are of past distinguished members. Reproduced by permission of the President and Council of the Royal Society. Wikimedia Commons.

The meeting place of the Royal Society

In a manuscript in the British Library, an anonymously reported fragment of conversation reads, “Mr. Cavendish rather wished to have the Presidentship.” This follows immediately after fragments attributed to Aubert and Smeaton

British Museum

In 1773 Cavendish joined his father as a trustee of the British Museum

The standing committee had a wide range of responsibilities, mostly having to do with routine matters, such as paying bills and performing audits, but there was also an unpredictable element. The committee routinely gave permission for visitors to copy documents and draw birds but also, on occasion, to examine human monsters under the inspection of an officer of the Museum. It heard standard complaints about the cold of the medals room and the damp of the reading room, but it also heard about the infighting of the staff, whom the committee ordered to stop quarreling and be amicable.58 It laid out money to buy or to subscribe to important works of science for the library such as Robert Smith’s System of Opticks and Samuel Horsley’s edition of Newton’s works.59 It noted gifts of books and collectibles. Just before Cavendish was elected a trustee, John Walsh

Society of Antiquaries

In the same year that he became a trustee of the British Museum, 1773, Cavendish was elected a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London. Described as a gentleman of “great Abilities, & extensive knowledge,” but with no mention of any accomplishments in antiquarian scholarship, Cavendish was recommended by Heberden

Originating with a group who met in a coffee house to discuss history and genealogy, the Society of Antiquaries was formally created, or re-created, in 1717. The leading spirit of the Society in its early years was the physician William Stukeley

The duty of the Society of Antiquaries

In 1770 the Society of Antiquaries

Cavendish became a member of the Society of Antiquaries at a time when the membership was rapidly growing, having nearly doubled in the ten years before his election.79 Many of the new members came from the upper classes, including the nobility. Many also came from science: in the same year as Cavendish, Franklin

Cavendish’s membership in the Society of Antiquaries together with his membership in the Royal Society and his trusteeship in the British Museum was inscribed on the plate of his coffin, but to Cavendish the affiliations were not of equal importance. He applied himself to the affairs of the Royal Society and of the British Museum, whereas he took no responsibilities in the Society of Antiquaries. He entered the record only once and then as an intermediary, submitting drawings of an Indian pagoda in the name of his scientific colleague Alexander Dalrymple.

There was a plan to bring together in the same meeting place the Society of Antiquaries, the Royal Society, the British Museum, and the Royal Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. It was only partly to be realized. In 1753 the Society of Antiquaries took over a former coffeehouse on Chancery Lane, and the British Museum moved into Montague house the following year. Twenty years later, the Royal Society began planning its apartments for its new location, Somerset House. Cavendish, who was much involved with that move, agreed with others on the Council that it would be a “great inconvenience” for the Royal Society to have any apartments in common with the Society of Antiquaries, or even a common staircase. The public apartments of the Royal Society “will be understood by all Europe, as meant to confer on them an external splendor, in some measure proportioned to the consideration in which they have been held for more than a century.”82 A week later the architect William Chambers

Footnotes

19 Dec. 1765, 6 Feb. 1766, Minutes of Council, Royal Society (UPA film ed.) 5:146–148, 153–154. It was resolved that no more than two foreigners a year would be admitted until their number fell to eighty.

Certificates, Royal Society. Dates of proposal: Anthony Shepherd, 2:242 (19 Jan. 1763); John Strange, 2:343 (early Jan. 1766) ; Francis Wollaston, 3:65 (3 Jan. 1769); Francis Maseres, 3:104 (31 Jan. 1771); John Cuthbert, 3:312 (7 Mar. 1765).

14 May 1767, Minute Book of the Royal Society Club, Royal Society, 5. William Ludlam (1769). “Ludlam, William,” DNB, 1st ed. 12:254–255.

14 May 1767, 30 June 1768, and 16 Feb. 1769, Minute Book of the Royal Society Club, Royal Society, 5. Archibald Geikie (1917, 91, 100).

26 Feb. 1767, 8 Dec. 1768, and 9 Feb. 1769, JB, Royal Society 26.

Certificates, Royal Society. Proposed: Timothy Lane, 3:73 (6 May 1769); Jean-Baptiste Le Roy, 3:161 (5 Sep. 1772).

Certificates, Royal Society. Elected: James Watt, 5 (24 Nov. 1785); James Keir, 5 (8 Dec. 1785); James Lewis Macie (James Smithson), 5 (19 Apr. 1787); H.B. de Saussure, 5 (3 Apr. 1788); Philip Rashleigh, 5 (29 May 1788).

30 Apr. 1789, Certificates, Royal Society 5.

Royal Society, Certificates. Elected: Pierre Simon de Laplace, 5 (30 Apr. 1789); Joseph Louis Lagrange, 5 (5 May 1791); Joseph Delambre, 5 (5 May 1791); Joseph Mendoza y Rios, 5 (11 Apr. 1793): Gregorio Fontana, 5 (10 July 1794); David Rittenhouse, 5 (6 Nov. 1794); J.H. Schroeter, 5 (19 Apr. 1798); Joseph Piazzi, 6 (11 Apr. 1803). Proposed: Franz Xaver von Zach, 6 (17 Nov. 1803); W. Obers, 6 (17 Nov. 1803); Carl Friedrich Gauss, 6 (17 Nov. 1803).

30 Nov. 1765, JB, Royal Society 25:663.

Lyons (1944, 197–204).

From a survey of the Minutes of Council, Royal Society 5–8.

Entries from 19 Dec. 1765 to 30 Nov. 1766: Minutes of Council, Royal Society 5: 143, 145–153, 155–158, 160–161, 163–164, 167, 169. Henry Cavendish (1921a). Henry Cavendish to James Douglas, earl of Morton, [9 June 1766], draft, in Jungnickel and McCormmach (1999, 531–533). Cavendish would later be appointed to a committee of eight to consider places for observing the transit. 12 Nov. 1767, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 5: 184.

It depends on how one counts. Committees were often renewed, sometimes becoming virtually new committees with the same or a redefined task.

Cavendish served on eight committees with Maskelyne and as many with Aubert.

From a survey of the bound volume of minutes of the Royal Society’s committee of papers, 1 (1780–1828).

The paper proposed a new and easy method for determining the difference of longitude. 19 Feb. 1789, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 7:201.

Thomas Birch to Philip Yorke, 13 June 1761, BL Add Mss 35399, f. 202.

Henry Cavendish, “On the Effects Which Will Be Produced in the Transit of Venus by an Atmosphere Surrounding the Body of Venus,” Cavendish Mss VIII, 27.

In addition to “Thoughts on the Proper Places for Observing the Transit of Venus in 1769,” letter to Morton, and “On the Effects […] by an Atmosphere,” Cavendish wrote these studies: “Computation of Transit of Venus 1761, 1769,” “Method of Finding in What Year a Transit of Venus Will Happen,” “Computation of Transit of 1769 Correct,” and “Computation for 1769 Transit,” Cavendish Mss VIII, 30–33.

Henry Cavendish, “Paper Given to Maskelyne Relating to Attraction & Form of Earth,” Cavendish Mss VI(b), 1:20.

Henry Cavendish, “Rules for Computing the Error Caused in Measuring Degrees of Latitude by the Attraction of Hilly Countries,” Cavendish Mss XI, Misc.

Henry Cavendish, “Attraction of a Solid on a Point in Its Surface,” Cavendish Mss VI(b), 11.

Nevil Maskelyne to Henry Cavendish, 5 Jan. 1773; in Jungnickel and McCormmach (1999, 538). Having made a copy, Maskelyne returned Cavendish’s “Rules for Computing the Attraction of Hills.” The preliminary version of that paper is Henry Cavendish, “Thoughts on the Method of Finding the Density of the Earth by Observing the Attraction of Hills,” Cavendish Mss VI(b), 2, 6.

The Royal Society’s experiment would differ from the French one in that the two stations were both on the mountain, one on the north side and one on the south side. Henry Cavendish, “On the Choice of Hills Proper for Observing Attraction Given to Dr Franklin,” Cavendish Mss VI(b), 3:1, 5. Among his manuscripts are extensive calculations of the attraction of conical hills with circular and elliptical bases. Other manuscripts treat specific mountains in Scotland, candidates for the experiment: Skidda, supposed to be a cone with a circular base, Maidens Pap, Ben Laas, and others. Cavendish Mss XI, Misc.

29 July 1773, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 6:185–186. The committee which met on 18 July to approve the resolution consisted of Cavendish, Barrington, Horsley, Maskelyne, Watson, and the secretaries Maty and Morton.

27 Jan. 1774, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 6:210–211. The spelling varied. In this entry of the Minutes, the mountain is written “Sheehalian Maidens Pap.”

6 and 27 Apr. 1775, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 6:267–269.

Nevil Maskelyne (1775b, 532).

Derek Howse (1989, 137–138).

After Daines Barrington, F.R.S., had spoken with the secretary Lord Sandwich, the Council of the Royal Society ordered the secretary of the Society to write to him proposing a northern voyage with practical and scientific ends. 19 Jan. 1773, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 6:160–161.

22 and 29 Apr. 1773, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 6:172–173. The instructions for Phipps’s voyage were drawn up by Cavendish, Maskelyne, Horsley, Montaine, and Maty. Charles Richard Weld (1848, 2:72). Henry Cavendish, “Rules for Therm. for Heat of Sea,” twenty-four numbered pages with many crossings-out, Cavendish Mss III(a), 7. “To Make the Same Observations on the Flat Ice or Fields of Ice as It Has Been Called,” part of a ten-page manuscript, ibid., Misc. There is a second draft of the instructions about ice fields among Cavendish’s journals, ibid., X(a). Cavendish’s instructions for the use of his father’s thermometer are quoted in Constantine John Phipps (1774, 27, 32–33, 142, 145).

Cavendish Mss IX, 41, 43.

23 Dec. 1773 and 20 Jan. 1774, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 6:205, 208.

Matthew Maty to Henry Cavendish, 26 Dec. 1773; in Jungnickel and McCormmach (1999, 541–542).

W.A. Spray (1970, 200–201). Howard T. Fry (1970, xiii–xvi, xx–xxi, 235).

Cavendish loaned Dalrymple £500 in each of several years, 1783, 1799, 1800, and 1807. Dalrymple needed money to pay debts due immediately. Upon his death, his administrator asked Cavendish to tell him how much was owed him. The matter was still pending a few years later when Cavendish died. “27 December 1811 Principal Money and Interest This Day Received of Alex. Dalrymple Esq. Exctr. £ 2873.3.5,” Devon. Coll., L/31/64 and 34/64.

James Horsburgh (1805). “Horsburgh, James,” DNB, 1st ed. 9:1270–71. Fry (1970, 253–255). Certificates, Royal Society 6: James Horsburgh (proposed 21 Nov. 1805).

Certificates, Royal Society 3:209, Robert Barker (proposed 15 Dec. 1774); ibid. 4:23, Josias Dupré (proposed 25 Feb. 1779). “Barker, Sir Robert,” DNB, 1st ed. 1:1128–29.

Certificates, Royal Society 3:237, James Cook (proposed 23 Nov. 1775); ibid. 4:56, James King (proposed 23 Nov. 1780); ibid. 5, John Hunter (elected 12 Jan. 1786); ibid. 5, John Thomas Stanley (elected 29 Apr. 1790); ibid. 5, Samuel Davis (elected 28 June 1792); ibid. 5, Isaac Titsingh (elected 22 June 1797); ibid. 6, William Bligh (elected 19 Feb. 1801).

16 Mar., 6 July 1781, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 6:397, 439.

2 Aug. 1781, ibid. 6:440–442: “A Report from Mr. Cavendish Concerning the Meteorological Apparatus.” The Society’s concern with placing the meteorological instruments continued, leading to a committee formed of Cavendish, Aubert, Heberden, Deluc, Watson and Francis Wollaston: 12 Feb. 1784, ibid. 7:62.

19 Jan. 1786, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 7:138. This committee consisted of Cavendish, Chambers, Aubert, Kirwan, and Shuckburgh.

“Notes of Conversations 1770–1790,” BL Add Mss 35,258, f. 15.

Richard S. Westfall (1980, 630, 634–635). Frank E. Manuel (1968, 266, 281). The domineering side of Newton probably would not have been Cavendish’s preference.

Cavendish was elected trustee on 8 Dec. 1773. Minutes of the General Meeting of the Trustees, vol. 3. His record of attendance over the years is in the Minutes of the British Museum: Committee, vols. 5 to 9; General Meeting, vols. 3 to 5.

Sometimes he attended all of the meetings, but often he came to only some. What was for him a less than exemplary attendance no doubt owed to the largely formal nature of its proceedings.

The order for amicable relations was made on 9 May 1777. Committee Minutes of the British Museum, BL, 6.

31 July and 11 Sep. 1778, ibid.

23 Apr. 1773, ibid., vol. 5.

Walsh’s gift was in January or February 1775, and Hunter’s was on 16 June 1775, Diary and Occurrence-Book of the British Museum, BL Add Mss 45875, 6.

Meeting on 13 Sep. 1776, Committee Minutes of the British Museum, BL, 6.

Cavendish was proposed on 21 Jan. 1773 and elected on 25 Feb. 1773; on 18 Mar. he paid his admission fee and was admitted to the Society. Minute Book, Society of Antiquaries, 12:53, 580, 610.

Of the twenty-one members of the Council of the Society of Antiquaries in 1760, eleven , including the president, were also fellows of the Royal Society, and of its ordinary membership forty-six were fellows of the Royal Society. “A List of the Society of Antiquaries of London, Apr. 23, MDCCLX,” BL, Edgerton 2381, ff. 172–175.

Peter Davall to Thomas Birch, 22 Apr. 1754, BL Add Mss 4304, vol. 5, f. 126. Daniel Wray to Thomas Birch, 7 Mar. 1753, BL Add Mss 4322, f. 111.

Francis Drake to Charles Lyttleton, 26 Jan. 1756, Correspondence of C. Lyttleton, BL, Stowe Mss 753, ff. 288–89.

The Royal Society’s committee of papers sent Burrow’s paper to the secretary of the Royal Society, having drawn red lines through the passages that Burrow had expressly addressed to the Society of Antiquaries. James Burrow to Thomas Birch, 18 June 1762, Birch Correspondence, BL Add Mss 4301, vol. 2, 363.

John Whitaker, “The History of Manchester,” 6 Dec. 1770, Minute Book, Society of Antiquaries, 11.

Samuel Pegge, “A Memoir on Cockfighting: wherein the Antiquity of It, as a Pastime, Is Examined & Stated; Some Errors of the Moderns Concerning It Are Corrected; & the Retention of It amongst Christians Absolutely Condemned & Proscribed,” 11, 12 and 19 March 1772, Minute Book, Royal Society of Antiquaries, 11.

Richard Gough on the purpose of the Society of Antiquaries’ publication, in vol. 1, 1770, of Archaeologia.

There are many letters from members of the Royal Society to John Ward, president of the Society of Antiquaries, professor of rhetoric at Gresham College, and F.R.S. He published frequently on antiquities in the Philosophical Transactions. He helped locate letters of the chemist Robert Boyle for the benefit of the Royal Society: Henry Miles, F.R.S., to John Ward, 10 Feb. 1742/41 and 13 June 1746, Letters of Learned Men to Professor Ward, BL Add Mss 6210, ff. 248–50.

In connection with a natural history of fossils, Emanuel Mendes da Costa wrote to John Ward to ask if certain Roman vases were made of marble or porcelain. Letter of 13 Nov. 1754, Letters of Learned Men to Professor Ward.

Concerned with Homer’s placement of Troy, John Machin wrote to John Ward: “My whole time has been employed in tedious and irksome calculations to adjust and settle the moons mean motion, in order to make a proper use of the eclipse at the death of Patroculus.” 23 Oct. 1745, ibid., ff, 230–231.

This “history of the rise and progress of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Sciences” was read at the meetings of 1 and 8 June 1758. The paper was kept in a folio with the purpose of entering “occurrences of our own time.” Emanuel da Costa, “Minutes of the Royal Society and the Society of Antiquaries,” BL, Edgerton Mss 2381, ff. 57–58.

Between 1770 and 1775, sixteen upper-class members, including Cavendish, were elected. Ibid., 150.

Henry Cavendish to William Norris, undated. This letter, which is in the library of the Society of Antiquaries, has to do with an extract by Alexander Dalrymple from a journal in the possession of the East India Company, evidently referring to an “Account of a Curious Pagoda near Bombay …,” drawn up by Captain Pyke in 1712, and communicated to the Society of Antiquaries on 10 Feb. 1780 by Dalrymple; published in Archaeologia 7 (1785): 323–332.

10 May 1776, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 6:302–303.