Charles Cavendish

For a man so well off, Cavendish’s will

At some point, probably when he resettled after his father’s death, Henry made an inventory of his and his father’s

Upon the death of Lord Charles Cavendish, there was a small, almost imperceptible change in protocol. In his publications in the Philosophical Transactions, Henry Cavendish’s name was no longer preceded by “Hon,” a courtesy title once removed.

Following his father’s death at the end of April, Henry was absent from the first two dinners of the Royal Society Club in May, the only dinners he missed that year.9 Writing to Henry in late May, John Michell

Cavendish was “educated and trained by his

Despite Charles Cavendish’s privileges, his life had a sad aspect. His wife died while he was still in his twenties, leaving him with two small boys to bring up. While in his teens, the youngest boy, Frederick, suffered an accident that left him impaired and dependent on his father, and his oldest son was socially impaired. Charles, it would seem, shepherded and sheltered Henry until he was ready to go into the world.

His life also had its gratifications. Within his family and in the wider society he took on strenuous duties, which he performed admirably. His scientific work was skillful and recognized. Of his achievements, the assistance he provided his intelligent and diffident son Henry was the most consequential. He died with the knowledge that Henry was in charge of his life and master of his chosen work, science.

Leaving Home

Charles Cavendish

Hampstead

Fig. 11.1: No. 34 Church Row, Hampstead. Between 1782 and 1785, Cavendish lived in a house at the end of this row next to the church. But for the automobiles, this street with its terraced houses and church looks much the same as it did then. Photograph by the authors.

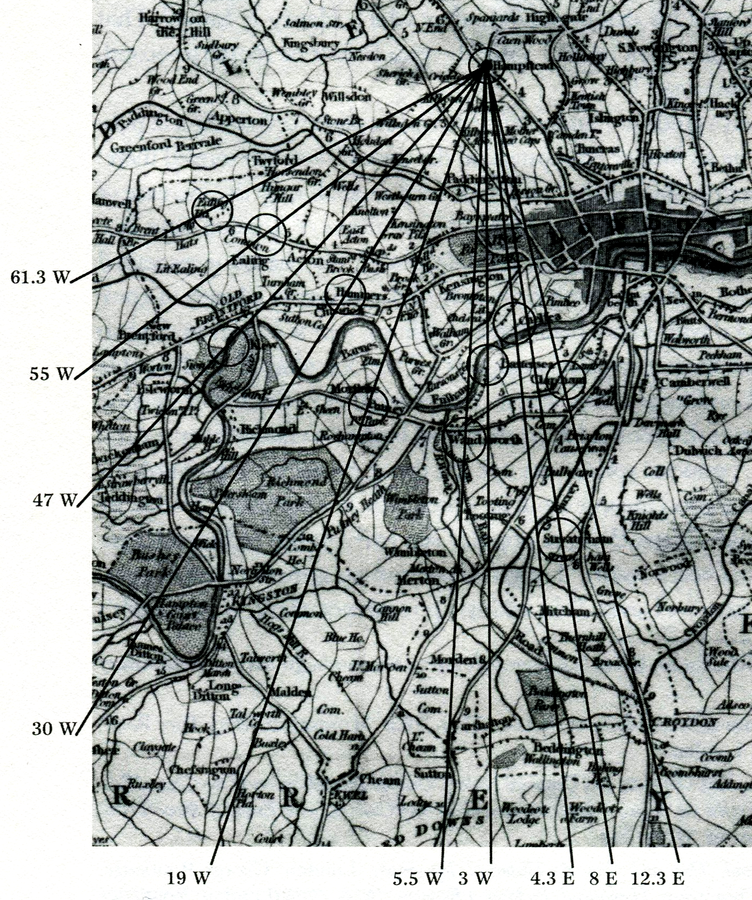

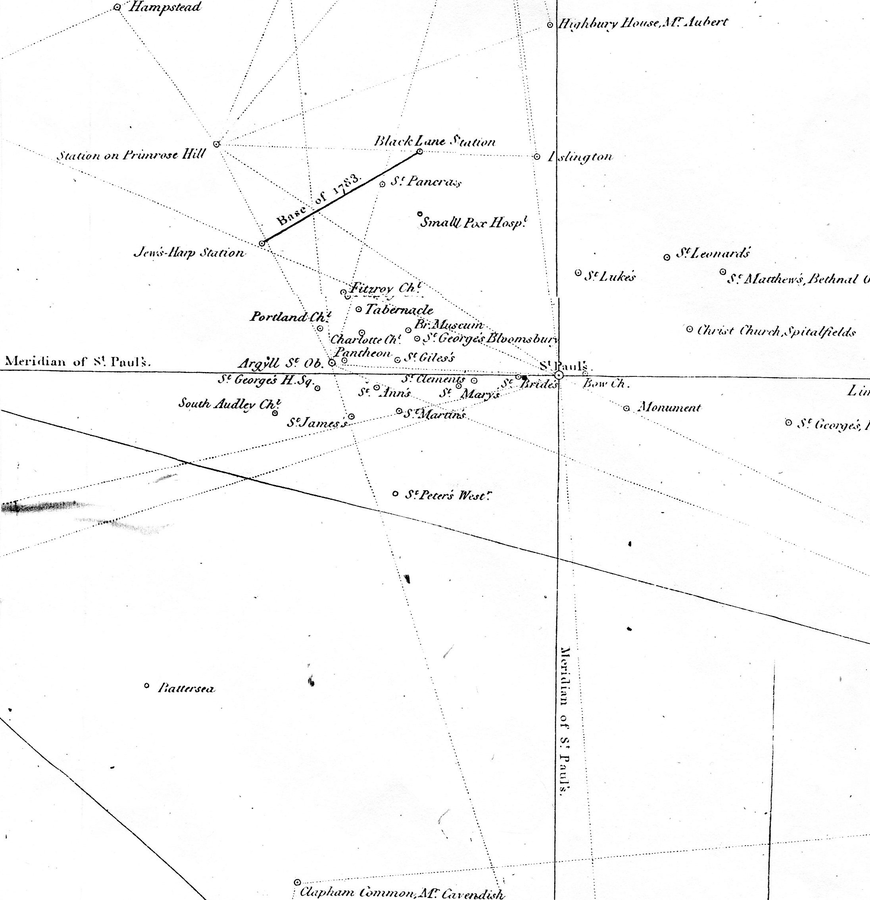

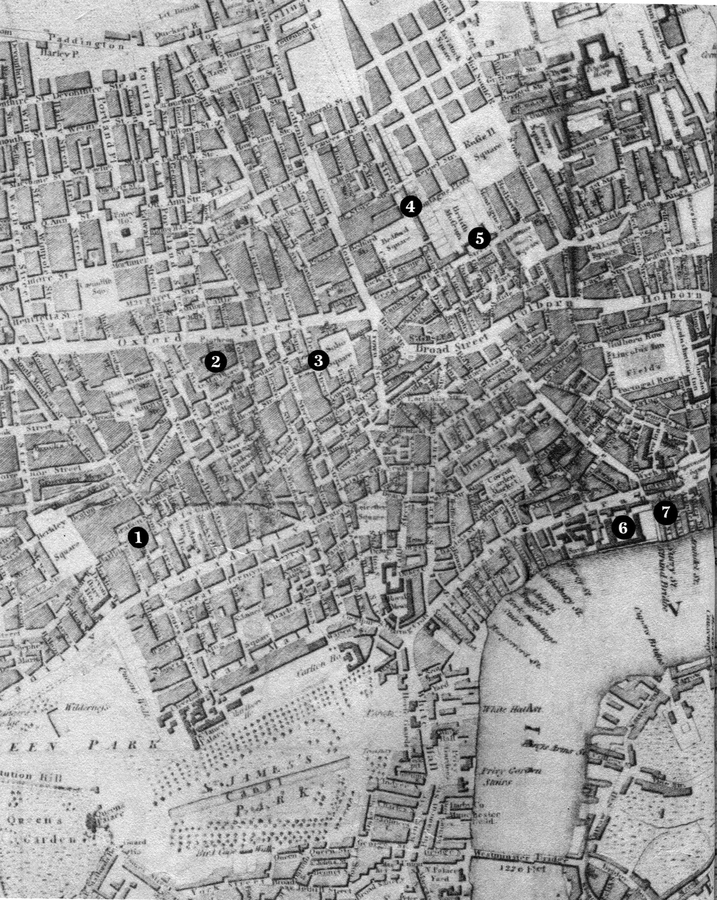

Fig. 11.2: Hampstead Bearings. From his country house in Hampstead, Cavendish took bearings in the direction of London. With a theodolite, he recorded the angular position of tall objects through an arc of about sixty degrees. Prominent among the objects were steeples, as we would expect from the picture of Westminster Bridge above; the London skyline was marked by steeples. On the map of London and environs published by R. Phillips in 1808, I have drawn Cavendish’s lines of sight for a number of steeples, labeling them with the angles he measured. From right to left: 1. New houses on the road to Clapham. 2. Streatham steeple. 3. Chelsea steeple. 4. Battersea steeple. 5. Wandsworth steeple. 6. Putney steeple. 7. Hammersmith steeple. 8. Kew Chapel. 9. Acton steeple. 10. Ealing steeple. “Bearings,” Cavendish Mss, Misc.

Fig. 11.3: Hampstead Environs. From his house at Hampstead, Cavendish made trips into the surrounding countryside, noting milestones and other markers, such as churches and villages, which we indicate by circles on this map of the portion of the County Middlesex directly north of London. Locations and mileages are from several miscellaneous sheets in Cavendish Mss.

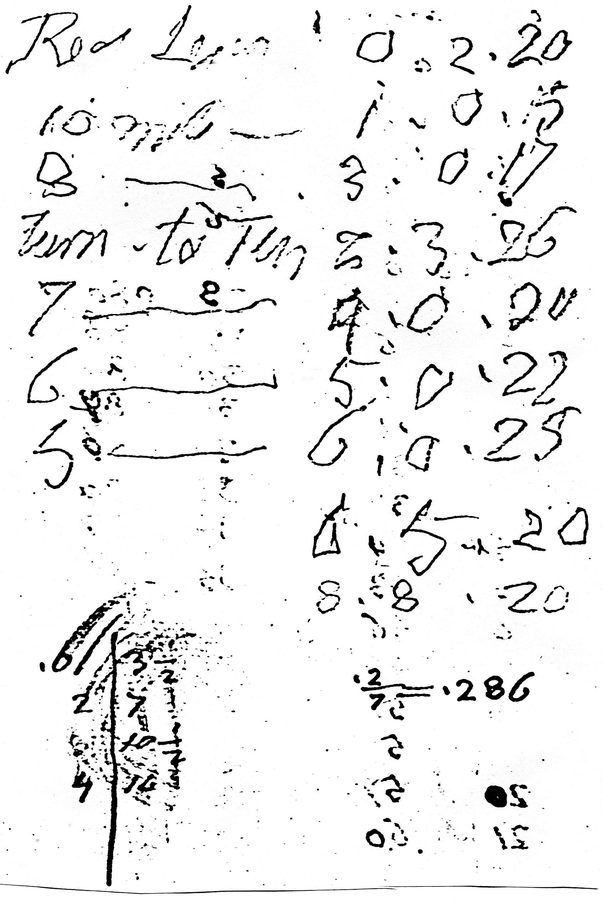

Fig. 11.4: Mileage Counter. This page was obviously written by Cavendish while moving, the unsteadiness of his hand giving an idea what travel was like then. The abbreviated place names are Red Lyon, about 8½ miles from his home, and Finchley Church, about 2 miles closer. Cavendish recorded several local journeys with a measurer, 35 revolutions equaling 1/10 of a mile. Between places marked on the map of the previous illustration, this table gives the distance in miles. We are not certain what his means of conveyance was when he took these measurements, but we know that he had an “odometer” attached to the wheels of his carriage. Such an instrument could be bought for 7 to 10 guineas, and it was thought to be accurate to within 1%. After Cavendish’s death, his “way-wiser” passed to the instrument maker Newman, who presented it to the museum of King’s College, London. It was there when Wilson wrote his biography of Cavendish, but according to our inquiry it no longer is. Benjamin Vaughan to Thomas Jefferson, 2 Aug. 1788, in Boyd (1956, 460). The sheet of distances is reproduced with permission of the Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement.

In the late seventeenth century, Hampstead began to change from a rural to an urban village. A mineral spring was opened, earning the village a reputation for healthiness as well as a good income from its water, which was recommended by physicians who drank it themselves. A popular destination early in the eighteenth century, Hampstead remained a resort, while its continuing growth owed to prosperous Londoners such as Cavendish taking up residence. Cavendish’s address was 34 Church Row, the street of choice in Hampstead, where visitors congregated and persons of “quality” promenaded. In appearance, the attractive, terraced houses have changed little since Cavendish’s day (Fig. 11.1).15

Cavendish’s activities were now divided between two locations, the exact separation of which was an astronomical datum: “Hampstead is 1,82 miles or 10.2 seconds of time west of Marlborough street,” he recorded.16 During the first spring at his new country house, he compared the good air of Hampstead with the foul air of the city,17 assisted by the instrument maker Edward Nairne

Bedford Square

For a time, Cavendish employed a young man Charles Cullen

In 1784 Cavendish leased his father’s house on Great Marlborough Street and the premises on Marlborough Mews behind it. Joshua Brookes

We do not know why Cavendish did not keep the house on Great Marlborough Street after his father died.24 Perhaps the house he moved to on Bedford Square had better arrangements for the library he intended for it, or perhaps he preferred the location next to the British Museum, where he regularly attended meetings as a trustee. Bedford Square may have had an intrinsic attraction too as the first garden square in London to exhibit perfect uniformity and symmetry in its architecture, features which may have appealed to his mathematical side.

Exactly when he relocated can be clarified. The rate books for the house give the occupants: 1782–84 Dr. Tye, 1784–86 Hon. John Cavendish

Bedford Square

Fig. 11.5: No. 11 Bedford Square. Front view. This was Cavendish’s townhouse from 1784 to the end of his life.

Fig. 11.6: No. 11 Bedford Square. Back of house. Photographs by the authors.

Bedford Square was relatively new when Cavendish moved there. Laid out in 1775–80, it was one of a number of squares built in the West End of London starting in the late seventeenth century. An early form of town planning, the squares imposed a degree of order on an otherwise sprawling metropolis. They came about as joint ventures between owners of large estates and builders, who were granted low-rent, long-term leases. According to a historian of eighteenth-century London, Bedford Square, which was built on the estate of the duke of Bedford, a relative of Henry Cavendish’s, was “probably the most important of the planned aristocratic building ventures of the century.”30 The houses followed a specified design, lending the square a standard appearance from all approaches. They were three-story with basements and attics, terraced, and built of brick, with wrought-iron balconies to the first-floor windows and entrance doors decorated by Coade stone with rounded fanlights above them. Each side of the square was a block of houses considered as a single unit, the center house set off by an ornamented stuccoed feature. Bounded by broad streets, the square was spacious, 520 by 320 feet between facing houses, with a large garden in the center for use of the residents.31

No. 11 Bedford Square, Cavendish’s house, which today is used for offices by the nearby University of London, carries a bronze tablet donated by the duke of Bedford identifying it as having once belonged to the chemist. In style the house is the same as that of the blocks of houses, but it does not physically join them. It is an end-of-row house on the northeast corner of the square, on Gower Street, with its entrance on Montague Place (Figs. 11.5–11.6). The neighborhood has long since been densely built-up, but when Cavendish moved there, Gower Street quickly ran into the fields. Today Bedford Square is one of the best preserved garden squares in London.

After Cavendish’s death, an appraiser wrote of the house, “I have scarce ever met with a more substantial or better built House, and the whole Edifice is finished with the best material.” The floors of the two main stories were made of Norway oak, the staircase was made of Portland stone, and the dining and drawing rooms had carved marble chimney pieces.32 All three stories and the attic for servants had bowed windows in the back looking out over a deep garden leading to the stables and coach house. The house had the quality, elegance, and expense expected of a wealthy Cavendish.

What is unusual is the use Cavendish

The house contained various pieces of furniture, evidently of the same quality as the house, some relating to what readers and writers require. The front drawing room on the principal floor had a pair of low steps, a pair of high steps, and a step ladder for reaching high shelves. It also had a glass-topped table, a column-and-claw table, four cushioned banister back chairs, two side desks, two black Wedgwood inkstands, and a table clock. The library

Library

From his father, Henry Cavendish inherited a good library, which he added to until the end of his life. For his work, a personal library was an asset, since scientific books and journals were not conveniently accessible. The British Museum owned and acquired scientific books, but its collection was inadequate for Cavendish’s needs, and the library of the Royal Society was very defective in just those subjects that interested Cavendish, works in natural philosophy and mathematics, according to a library inspection in 1773.37

Unlike the Cavendishes, most persons interested in science in the eighteenth century could not afford to buy or to subscribe to many scientific books and journals, relying instead on private libraries made available to them upon application to their owners. In England, large scientific libraries like Hans Sloane’s

At an earlier time Cavendish may have kept his collection at another location. According to his biographer Wilson

Despite Cavendish’s reputation for clockwork routine

The first we hear of Cavendish’s librarian is in 1785, the year after Cavendish moved to Bedford Square. He was almost certainly a German by the name of Heydinger

To a prospective user of the library

One of Cavendish’s librarians was the beneficiary of a remarkable instance of Cavendish’s largess. This librarian lived in Cavendish’s house until he left his employment and moved to the country. Some while later Cavendish was told that the man was in poor health. Cavendish was sorry to hear it, and when it was suggested that he might help him out with an annuity, he said, “Well, well, well, a check for ten thousand pounds, would that do?”52

A few years after Cavendish’s death, the sixth duke of Devonshire

The catalog of Cavendish’s library is incomplete, extending only to the early 1790s, and because he continued to buy books after that time, we can speak more accurately of the contents of his catalog than of his library. Books in Latin and books in English appear in roughly equal proportions in the catalog, each accounting for about one third of the total, with books in French coming next, and then, in sharply reduce proportions, books in German and in other European languages. The catalog lists about 9000 titles, representing some 12,000 volumes,55 showing that Cavendish had a large library, but not an immense one for the time. Sloane’s library, the foundation of the library of the British Museum, was four times as large, and even Cavendish’s seafaring friend Alexander Dalrymple

Cavendish’s library was open to the qualified public, but its contents were not selected with the public in mind. The largest category in the catalog was natural philosophy, with nearly 2000 titles.58 In this same category were many books on medicine, anatomy, and animal economy, very few of which were published after Charles Cavendish died. Mathematics, the second largest category, included in addition to books on pure mathematics, books on natural philosophy in which mathematics was used, such as Newton’s Principia and Opticks and Robert Smith’s System of Opticks. Astronomy was a category of its own and well represented, including classic works of science by Copernicus, Brahe, Kepler, and others. In the natural history of life, Cavendish had only slight interest, but he was interested in other parts of natural history, buying many books on mineralogy and geology. He took an interest in books on voyages and travels, which related to his scientific work. About half of the books in the catalog were scientific. The category of poetry and plays was as large as that of mathematics, some 1100 volumes, including works by Shakespeare, Dryden, Congreve, Pope, Swift, Gray, and other authors one would expect to find in a literary library. After Charles’s death, when Henry alone added to the library, there were no more books of poetry or plays, with the exception of an Indian drama.59 Henry had a passing interest in history and antiquities, which were separate headings in the catalog, with several titles having to do with India. His catalog had no division for histories of individual lives, or biographies, though he bought The Life of Samuel Johnson

Often libraries are revealing through their owners’ marginalia. It seems that Cavendish rarely put a mark in a book; in the third edition of Newton’s Principia, he (or someone) penciled in a few numbers, and in a speculative treatise on attracting and repelling powers by Gowin Knight, he (or someone) made a couple of penciled notations.61 Cavendish’s library holds few surprises. It is confirming, not revealing; it tells us that he was interested in the physical sciences and mathematics and not in literature and languages

Clapham Common

In his scientific calling, Cavendish followed his father, and as an aristocrat who owned houses he again followed his father. As we know, when Charles Cavendish married, he bought a country estate, and if his wife had lived, we might expect him to have continued the familiar living arrangement of a gentleman, having two homes, one in the city and one in the country. Instead, five years after she died, he sold it and bought a townhouse on Great Marlborough Street, so far as we know living the rest of his long life without keeping a second home in the country. His activities were in the city, and he may have felt that as a single man he had no need for a second home, and there may have financial considerations. His oldest son, Henry, also had two homes, his second one coming late in life. Father and son held to patterns of living fairly common among men of their station and means.

In 1785, Cavendish bought a country house on Clapham Common

We first hear of Cavendish’s interest in Clapham Common from letters that passed between him and Baldwin beginning in the spring of 1784. Both were members of the Monday Club, which may be where Cavendish learned about the property.65 The two men met to discuss it, and at the close of a letter following their meeting, Baldwin wrote, “I wish among your other learned & very curious investigations in our atmosphere, you would tell me when I may safely begin hay-making, since you are interested in the attempt.”66 All business, Cavendish paid no attention to pleasantries and flatteries like this, beside which he knew better than to predict the weather.

Baldwin understood that Cavendish wanted to buy three contiguous parcels of land consisting of about fifteen acres adjacent to his house for the purpose of building a house on it. When he was first approached by Cavendish, he said that he was not interested, and he suggested other owners who might sell him land. When difficulties arose with another property, Wright’s farm, Cavendish’s agent Thomas Hanscomb returned to Baldwin.67 Baldwin asked Cavendish to tell him what he would pay for the land. When Cavendish said £5000, Baldwin said that it did not meet what he called the “market price.” Two of the three parcels of land were choice; the remaining “front land” on the Common could not be valued by the acre any more than could land in London or Westminster. Pointing out the beauty, the health, and the convenience of the parcels, Baldwin said that Cavendish should come look at them himself “before it’s too late.” Baldwin calculated the value for the three parcels separately, the total coming to £5650, which he said was £1280 below the market value. To come up with “a few hundreds more” ought to be no consideration, he said, for “a gentleman of your high rank & well-known great opulence,” but Cavendish refused to bargain, and in due course Baldwin accepted his offer.68 Mortgages on the fifteen acres caused delays in closing the sale until the winter of 1784. The purchase was absolute, the parcels belonging to Cavendish and his heirs and assigns forever. Cavendish named his closest scientific colleagues in London, Blagden

As it turned out Cavendish did not build a house for himself on the fifteen acres. Instead he entered into an agreement with builders Hanscomb, Richard Fothergill, and Thomas Poynder, who were bound to spend a specified minimum amount of money within a specified time to erect substantial houses with coach houses and stabling. When the buildings were completed, Cavendish would join with them in granting separate leases for the houses, with covenants prohibiting the building of brick kilns or using any buildings on the property as public houses or shops “for carrying on any noisome or offensive trade or business.”70 The land was to be used for up-scale residences, insuring a proper tone. Cavendish arrived at Clapham Common as an eventual land developer and landlord.

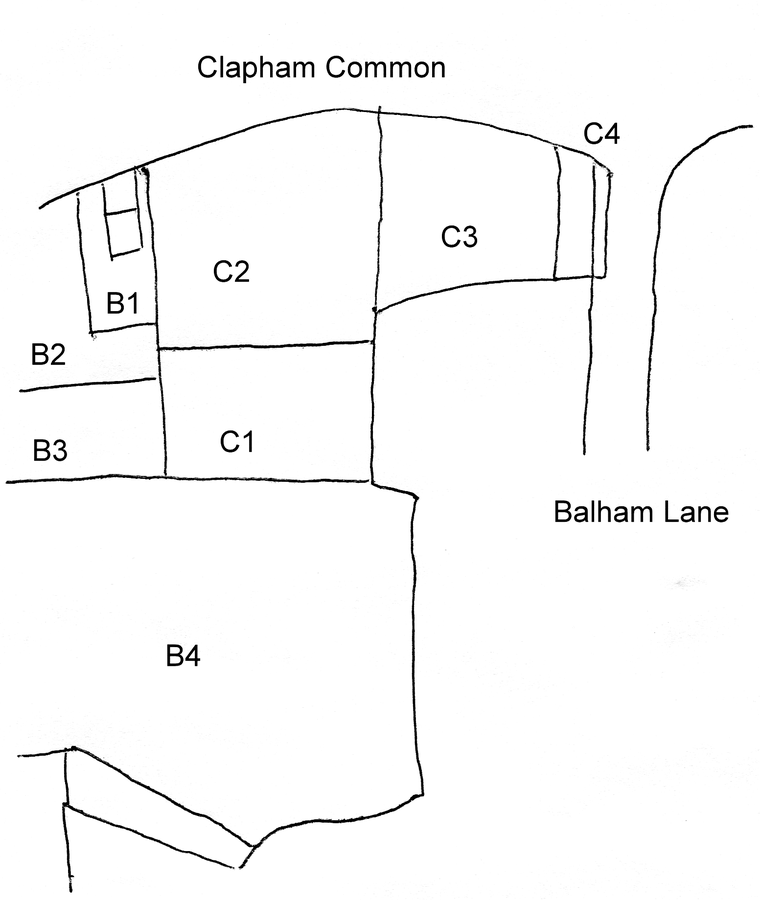

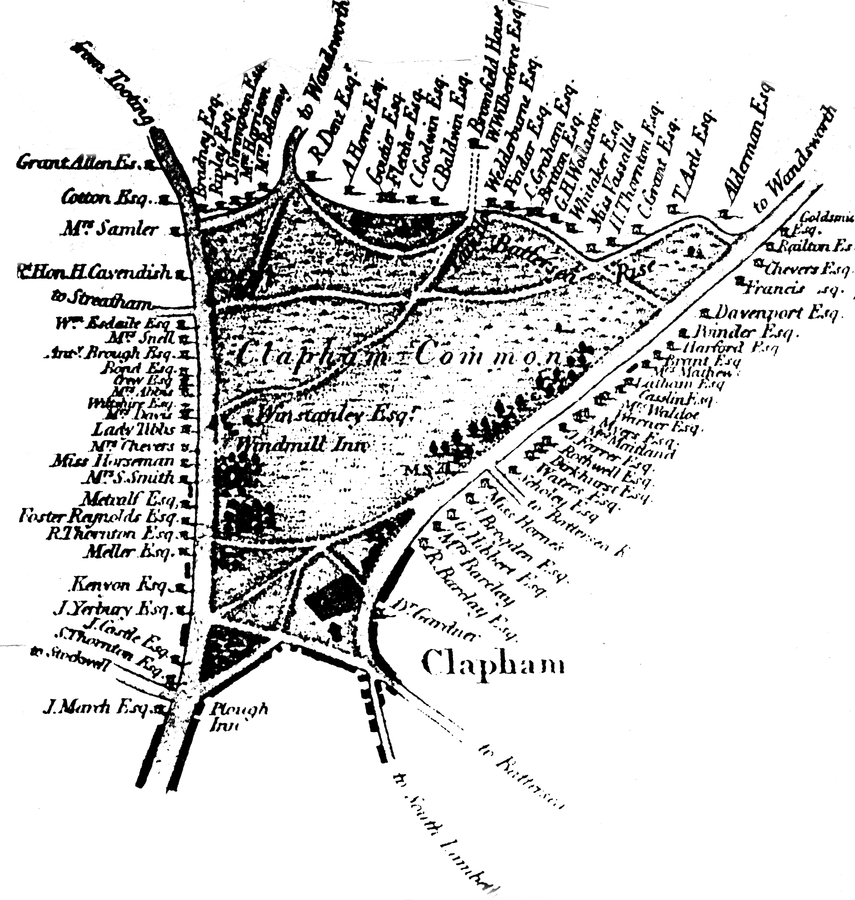

Fig. 11.7: Map of Cavendish’s Land on Clapham Common . C1, C2, and C3 are three parcels of land, totaling roughly fifteen acres, which Cavendish bought from Christopher Baldwin in 1784. C4 is a slip of land Cavendish bought from Baldwin later. B1 is Baldwin’s house and garden. B2, B3, and B4 are fields owned by Baldwin. “Abstract of the Title of His Grace the Duke of Devonshire to an Estate at Clapham Common in the County of Surrey,” 2 November 1784, Devonshire Collections, Chatsworth, 38/78.

It is unclear exactly what Cavendish’s plans were for relocating on Clapham Common. As early as May 1784, at the time he began negotiating with Baldwin over the fifteen acres, presumably to build a house on, he considered buying an existing house, “Mr. Mount’s house,” which was probably “Mrs Mount’s house” on property adjacent to the house that Cavendish bought the following year.71 What is certain is that his mind was set on moving to Clapham Common, which was not as smokey as London, an advantage when making astronomical observations, and it was healthier, as Baldwin claimed. His house would be a villa, with spacious grounds in a pastoral setting with fine trees, pastures, and ponds, again as Baldwin said. In addition to the peace and quiet of the place and to the privacy it offered, it was also convenient: Baldwin explained that there were good roads, which enabled inhabitants of Clapham Common to travel to London, cross over London Bridge, do business in the city, and return by way of Westminster Bridge, which was no further away from home.72

In June 1785, Cavendish bought a house on another side of the Common from his fifteen acres. Perhaps the house became available only after he bought the land from Baldwin. Perhaps its readiness appealed to him, for by buying an existing house he did not have to wait, and he avoided the aggravation of building, allowing him to return to his researches with a minimum of interruptions. It is also possible that Cavendish intended from the start to develop the fifteen acres rather than to build a house for himself there, though it is unclear why he would want to.73

His house was three-story, double-fronted, and “symmetrically planned and with a central doorway of typical Georgian design,” with considerable grounds.74 From a plan of the Common in 1800, it appears that with one exception, Cavendish’s property occupied the largest frontage of the sixty-odd residences (Fig. 11.12). The lease tells the history of ownership of the house: “Assignment of lease. 18 June 1785. 1. William Robertson

Cavendish’s house has been called a mansion, but a better description of it from the time is “a tolerable good house, built with red brick.”78 Later owners of the house greatly changed the appearance of the house inside and out, making it difficult to get an idea of the original layout, the number and uses of the rooms, and other details.79 It was made into a structure that could be called a mansion: among the additions were a magnificent reception room, another servants’ wing, a terrace along the garden frontage, and an extension for hanging paintings. At some point, the original red brick central block, the house as Cavendish knew it, was stuccoed over. In 1880, the house was described by an auctioneer as containing “an elegant drawing room, noble dining room, handsome library, morning room and billiard room, a large conservatory, and seventeen bedrooms,” and the park-like grounds were similarly sumptuous. Cavendish would have been hard-pressed to recognize the sensible building he made into a house of science in 1785. In 1905, the estate was sold and the house was torn down, replaced by rows of red brick villas.80 Cavendish Road, originally Dragmire Lane, memorializes the place where Cavendish’s house once stood.

We know some of the alterations Cavendish made to the house: from an instrument maker who saw the house, we learn that he converted the drawing room into a laboratory, the room next to it into a forge, and upstairs rooms into an astronomical observatory. A tree behind the house was used as a platform for making scientific observations,81 and soon after Cavendish arrived, he erected an eighty-foot-tall ship’s mast, with a horizontal arm, for mounting an aerial telescope.82 (Figs. 11.8–11.13). This most conspicuous feature of Cavendish’s property would have told the neighbors, if they did not already know, that the new resident on the Common was different. He acquired a local reputation as a wizard.

In the middle years of the decade, the 1780s, Cavendish was kept busy moving from one house to another. He explained to Joseph Priestley that a reason he was so long in replying to a letter was that he had been prevented from making any experiments during the summer by “the trouble of removing my house.”83 The move to Clapham was particularly disruptive of his regular life. In June 1785, he postponed the beginning of a journey with Blagden

In his letter to Laplace, Blagden said that Cavendish would have “conveniences for carrying on his experiments to still greater perfection” in his new house.87 That may have been, but Cavendish’s most important work was done in his first twenty-five years

Cavendish sometimes stayed at his house on Bedford Square

Other comparisons of Cavendish’s two houses reinforce our picture of his life. The value of the furniture in each house was essentially the same, £645 at Clapham Common and £633 at Bedford Square, but his plate, China, and linen at Bedford Square were valued at £700, and at Clapham Common £168.

Clapham Common

Fig. 11.8: Cavendish’s House on Clapham Common. Demolished. This was Cavendish’s country house from 1785 to the end of his life. We see the back of the house, much altered since Cavendish lived there. Frontispiece to The Scientific Papers of the Honourable Henry Cavendish (1921g). All rights reserved: Cambridge University press. Reprinted with the permission of Cambridge University Press.

Fig. 11.9: View of Clapham Village from the Common. William Thornton (1784, 490).

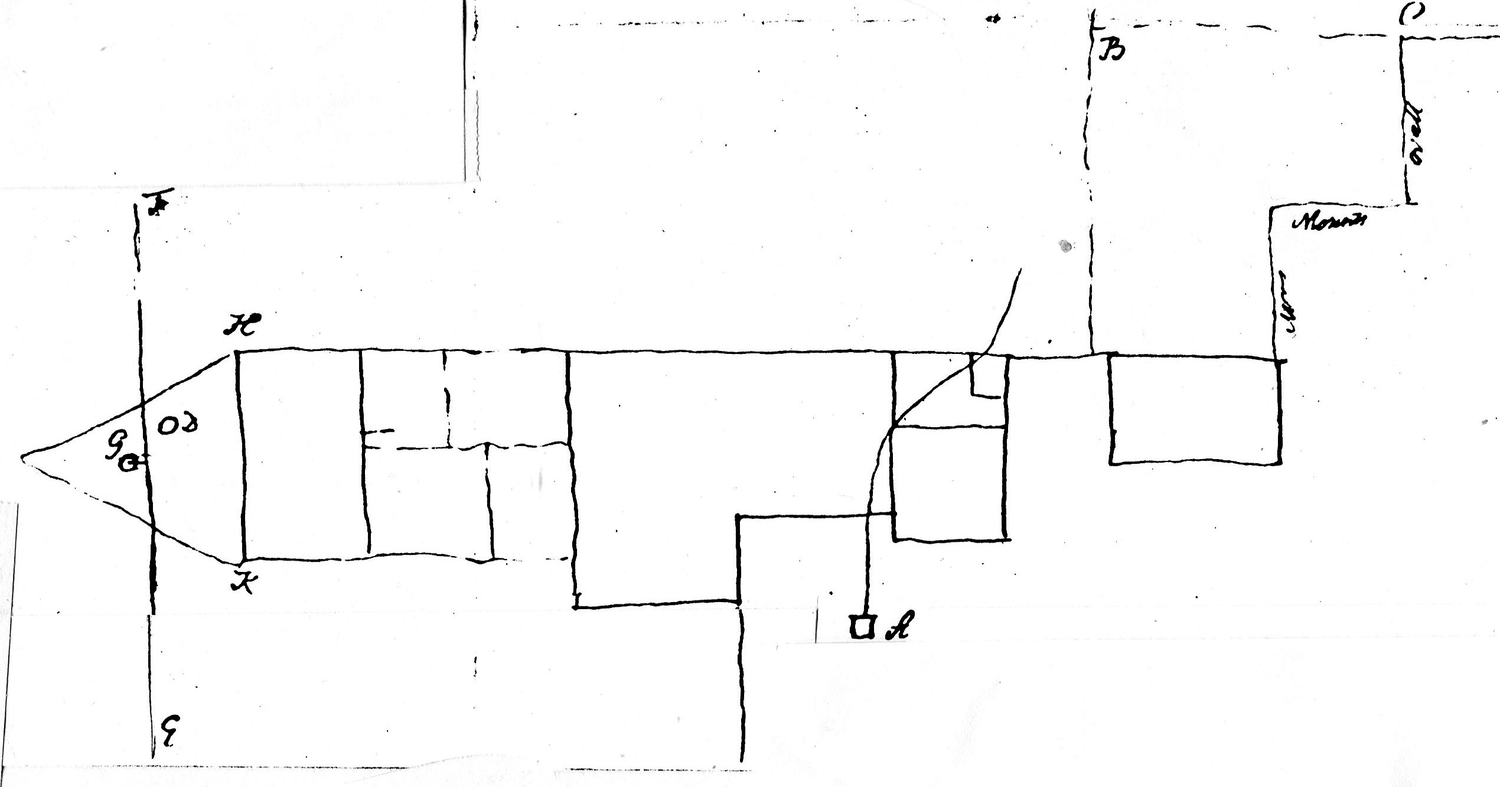

Fig. 11.10: Plan of Drains at Cavendish’s House. Cavendish’s house faces Clapham Common at the bottom of the diagram. The separate building to the right is evidently a greenhouse, formerly containing an outhouse, which Cavendish refers to in his notes on experiments on air. To the left is a basin that becomes a pond, 7½ feet deep, into which the drains from H and K run, and which is filled from the pipe EF, which probably comes from the pond across the road in the Common. G is the valve for letting water into the pond. The other letters stand for: A, a drain sink; B, the gate to the kitchen garden; BC, a drain running from Mrs. Mount’s house to the right of what Cavendish has labeled Mrs. Mount’s wall; D, a well formerly supplying the pantry or dairy. Water from A eventually runs into a ditch in the field behind the house, and from there it is conducted to the “lane,” presumably Dragmire Lane, which bounds Cavendish’s property. Next to the pond is a sundial, which Cavendish used as a marker in taking measurements of the basin. Cavendish refers to his walled “courtyard,” but he does not indicate its location. This diagram was probably drawn up in connection with renovations Cavendish made before moving into the house in 1785. Cavendish Mss, Misc. Reproduced by permission of the Chatsworth Settlement Trustees.

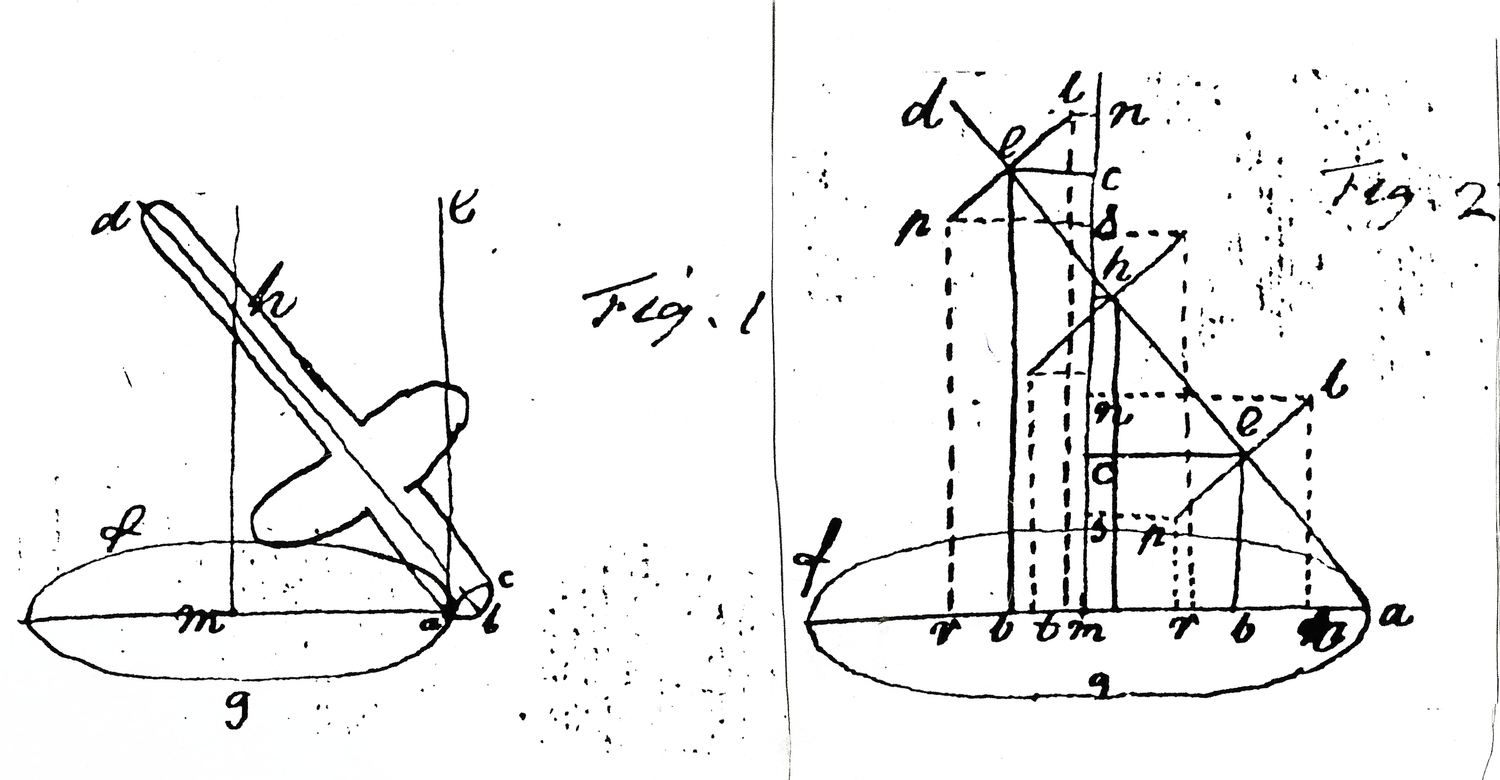

Fig. 11.11: Mast for Aerial Telescope. The drawings accompany computations for an eighty-foot-high mast for mounting the Huygens lenses belonging to the Royal Society. Cavendish erected the mast on his grounds at Clapham Common. Cavendish Mss, Misc. Reproduced by permission of the Chatsworth Settlement Trustees.

Fig. 11.12: Map of Clapham Common. Cavendish’s house is on the left side of the Common, fourth from the top. “Perambulation of Clapham Common 1800. From C. Smith’s ‘Actual Survey of the Road from London to Brighthelmston.’” Burgess (1929, opposite 112). Reproduced by permission of the Bodleian Library.

Fig. 11.13: Triangulations around London. Triangles measured by the British surveyors showing their starting point, the baseline of 1783 on Hounslow Heath. The purpose of laying down secondary triangles was to improve plans of London and maps of the country. Cavendish’s observatory at Clapham Common, shown at the bottom of the map, is one of the stations. Roy’s observatory on Argyll Street is shown, as are Aubert’s observatories at Highbury House and at Loampit Hill. Greenwich Observatory is just to the right of Loampit Hill, off the map. Detail from a map by Roy, appended to “An Account of the Trigonometrical Operation” (1790).

He kept his small wardrobe and his carriage and harness at Clapham Common, his pictures and wine (twenty-two bottles of port, tokay, and white wine, and ten dozen empty bottles) at Bedford Square.90

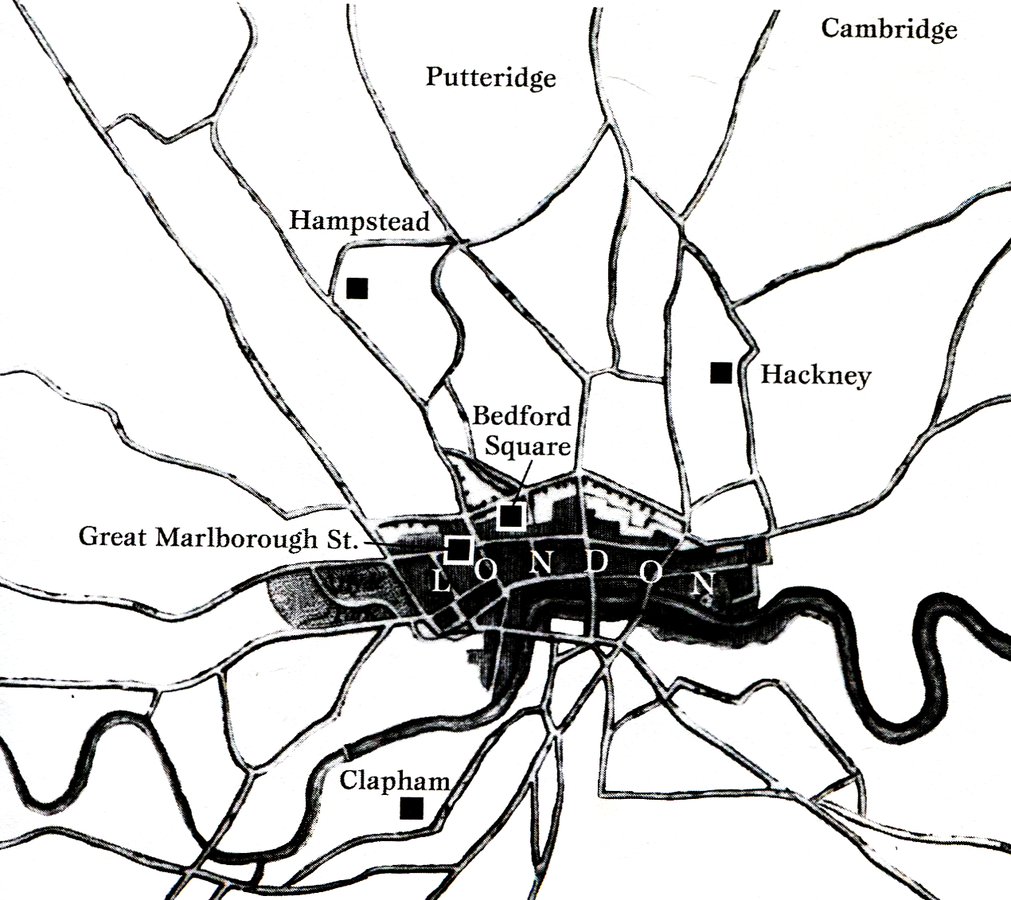

A map of the places Cavendish could call home reveals a paramount fact about him: he was a city man. When he lived outside of London as an adult, he was no further away than a suburb, probably within sight of the spires of the city. He owned properties in the countryside, but he had no thought of living there. London offered him the civilized amenities and learned company he needed for his chosen way of life

Fig. 11.14: Places Where Henry Cavendish Lived. All of the places on this map are mentioned in the book. It shows that although Henry Cavendish did not always live in London, London was never far away.

Land Developer

Cavendish had further business to settle on Clapham Common

The dispute over the £40 was not yet settled when another problem arose. Dunn had heard that the people of Clapham planned to pull down all of the fencing on the Common and that Baldwin knew about it, in which event Cavendish “must not give him a farthing for the piece of ground,” since it encroached on the Common. Learning of this objection, Baldwin wrote to Cavendish, “In my whole life I never was so heartily tired of any thing as I am of the un-meaning correspondence into which I have been drawn by you and your attorney… I am buried in the letters founded in error and ignorance.” Baldwin was not going to accept £40, and it was not true that the people of Clapham were going to pull down the fences. It was true, Cavendish told Baldwin; moreover, he was informed that the people of the neighboring parish of Battersea planned to tear down the fences on their common unless the owners paid them a “composition.” Cavendish said that he was “so confident” of his information that he was no longer prepared to pay Baldwin the £40, but only £40 less the composition. Baldwin warned Cavendish not to stir up the people of Clapham by spreading the idea of tearing down the fences. Cavendish replied that if Baldwin did not accept his offer, £40 less composition, and make over the rights of the property in two or three days, he would take it as refusal and act accordingly.92

Cavendish asked for a “direct answer,” but Baldwin’s answer was anything but direct. He asked about Cavendish’s intention to build a fence between their properties. Even before Cavendish bought the fifteen acres from him, Baldwin had sent him “Hints for Consideration,” advising him about building fences.93 Later Baldwin told Cavendish that his fences were ruined, allowing cattle to enter Baldwin’s garden from Cavendish’s fields. Baldwin ordered Cavendish immediately to procure the oak pailing for the fence between their properties. The fence, Cavendish replied, “would have been put up long before now if I had not waited till the dispute about the ground taken in from the common was settled.” He told Baldwin that he would observe his agreement about the fence “but will not be prescribed to about it nor bear your delays or cavils.”94 He told Baldwin to come to Dunn’s on Wednesday

Fig. 11.15: Map of Cavendish’s London

Fig. 11.16: Map of Cavendish’s London

or Thursday, where he would be waiting to execute the deed. If he did not come Cavendish would give him nothing for the land. Baldwin wrote back asking Cavendish what he meant by saying that he would observe his agreement about the fence. The correspondence between Cavendish and Baldwin came to an end with a flurry of letters, four of them passing between them on one day, the first Saturday in May 1786. Cavendish wrote: “I can not at all conceive what is the cause of this behavior whether you have any private reason for wishing to delay the agreement or whether you distrust my honour about the pailing & wish to make some further conditions about it. If the latter is the true cause you may assure yourself that I will never submit to make any such conditions or explanation with a person who distrusts my honour.”95 A few days later the papers were signed conveying the property to Cavendish.96 Cavendish’s business with Baldwin had taken nearly two years.

Both in the original sale of fifteen acres and in the consequent disagreements over the slip of land, Baldwin misjudged Cavendish. Baldwin thought that money was the issue, and for him no doubt it was, given his large debts. To Cavendish, the matter of Baldwin’s legal expenses, £60 or £40 or £40 less composition, was one not of money but of principle. Baldwin’s

Man of Property

Charles Cavendish owned farms and tithes in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire

Charles introduced his eldest son to business as he had to science, turning over the management of his estate to him in the summer of 1782. Charles did not yet formally make it over, and he continued to participate in its management,99 but he allowed Henry to receive the income from rents, tithes, and land taxes, which came to around £1600 a year. In his manner of handing over responsibility, Charles repeated his own experience, his father having turned over the rents to him in the first year and in the second year the property itself. From Henry’s point of view, it was time to begin leaving home; land, we suspect, was equated by him with independent living.

Henry Cavendish’s activity as an absentee landlord gives us insight into his person. Like his father, he had first to settle on a steward. Unsatisfactorily as he had worked out, Revill had an extenuating circumstance, which he had explained to Charles Cavendish. Because of a problem with his throat, he could scarcely speak and was reduced to communicating by writing, though he was helped in his work by a nephew.100 Revill’s attitude, a mix of servility and arrogance, was exasperating, but his difficulty in speaking no doubt helps explain the roundabout way he went about his work. His new master Henry Cavendish, who himself had difficulty in speaking, evidently felt no bond of sympathy, neither making nor accepting excuses for Revill’s lapses.

The duke of Devonshire was well served by his agent J.W. Heaton, who recommended William Gould

In Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, the Cavendish family had long counted among the big landlords who bought out the landed gentry and took over their manors.103 Charles and Henry’s properties were in the neighborhood of the duke of Devonshire’s, from which they had been separated off.104 The duke’s main country house was in the region, at Chatsworth in Derbyshire. Family estate records were kept Hardwick Hall, nearby in Nottinghamshire, where Henry Cavendish directed his steward to examine documents.105 The Cavendish family kept in touch on matters of property. When one of Henry’s properties became available a prospective tenant approached him through his first cousin John Cavendish

Under the old pattern of farming, tilled land was parceled into strips with mixed ownership, and pastures were subject to common right. To meet changing economic needs, this pattern was replaced by one in which strips were consolidated and common use of land was reduced; the device was called enclosure.107 The practical intent of enclosure, as Charles Cavendish put it with his usual clarity, was to “lay each person’s allotment together as much as can be.”108 If landowners could not agree on enclsure an act of Parliament was required to overcome local resistance. Enclosure was a costly improvement: landowners were out the expense of passing the act; fees for lawyers, surveyors, and commissioners, whose job was to carry out a survey, place the owners’ allotments in enclosed fields, see to it that improvements specified in the act were built, and look into damage claims; and a very considerable capital investment in fences, drains, roads, and various structures.109 Because substantial economic gains could be expected from enclosure, big landlords and farmers were for enclosure. Charles and Henry Cavendish were not big landowners, and they could not avoid conflict.

Their property in the parish of Arnold in Nottinghamshire is an example of the complications attending enclosure. Charles Cavendish was entitled to tithes from the use of the land at Arnold, from which he received rent twice yearly, the total of which, a little over £100, made Arnold intermediate in value among his properties. In the event of enclosure, Cavendish would be expected to forfeit his tithes in exchange for an allotment of land. Just how much and what kind of land were the question.

In 1776, the proprietors at Arnold considered petitioning Parliament to enclose their land. The quantity of land and the amounts given over to different uses were imprecisely known, since there had been no survey. Proceeding from incomplete information Revill made proposals to the proprietors about what share of the common fields and forest Charles Cavendish should receive in return for giving up his tithes. Revill’s proposals were ill-received by the proprietors, whose spokesman repeatedly appealed to Cavendish and brought their grievances to him in person. Cavendish wanted the proprietors to deal with Revill, but they objected to him even more than they did to his proposals. Because of the animosity between the people at Arnold and Revill, agreement looked all but impossible. Revill asked for more than was “just,” Cavendish said, and he urged reason and negotiation.110 The matter of the Arnold enclosure languished, but several years later, it came up again in the form of a petition for a bill. Having just taken charge of his father’s farms, Henry Cavendish inherited a local history of bad feeling

Henry’s new steward told him that recent enclosures had been “attended with great detriment and injury to the estate,” by which he meant not the unavoidable “great sums that have been expended on those Inclosures and the Buildings upon them” but the avoidable, absolute loss in the value of the estate owing to the previous steward’s inattention. Cavendish entered into a long negotiation with the proprietors at Arnold over the amount of land he was entitled to receive in lieu of tithes, his father’s quandary. In principle, the land he was entitled to receive was equivalent in rental value to the tithes he would have received from the improved land after enclosure, but the comparison of values was not straightforward. Depending on how it was figured, either the farmers or Cavendish benefited more. The proprietors took the initiative, offering Cavendish a specified allotment of land to compensate him for the loss of his tithes. Gould calculated the rent Cavendish would receive from the allotment, deducting the interest he would pay for putting up fences and buildings and for vicarial tithes, which he would go on paying, coming out to £169 per year, far below the £250 Gould estimated that Cavendish’s tithes would bring. Because of the expenses Cavendish would incur, Gould advised him not to accept an allotment of yearly value less than £360. It was fair, Gould said, but the proprietors would not like it.112 Cavendish did not like it either. If a specific monetary value were proposed, he told Gould, he would come out a loser, because the commissioners routinely overvalued land; instead he wanted them to allot him a certain “proportion” of land, a surer measure of value than money.113 Gould then wanted to select the location of the allotment on the forest. Cavendish thought that he was being overly zealous, making unnecessary trouble for the commissioners, who might be “less disposed to do me justice,” but otherwise he accepted the proportion Gould had calculated for him. The proprietors rejected the proposal; their spokesman said the land would rent for £500, and he knew a man who would pay it. The spokesman complained about Cavendish’s steward, who refused to answer letters, attend parish meetings, or receive a delegation, exhibiting “all the insolence of delegated authority.”114 Gould, if the proprietors were to be believed, was behaving like Revill. Cavendish did not mention the proprietors’ complaints to Gould, which in any event could hardly have been news to him. He wanted Gould to get more exact information on acreage, rents, and tithes, for only then could they “prove” that their proposals were not “unreasonable.” Fairness in this matter depended on reason, facts, and calculations, even though the quantities involved could be no firmer than estimates. Cavendish told Gould that justice all around would be served only if his “estate should be improved in the same proportion as that of the land owners,”115 and his duty to his estate was to ensure that it received this proportion.

The “affair of Arnold,” as Cavendish called it, dragged on for years.116 Early in 1789 Gould told Cavendish that enclosure was likely, but a little later he corrected himself; it was unlikely because the vicar wanted more for his tithes on turnips and lambs than the proprietors offered him, and the vicar was a hard bargainer. Gould then learned that the landholders intended to go to parliament without the vicar, leaving the new allotments still subject to vicarial tithes, which meant that Cavendish would have to be given additional land equal to the tithes he must pay the vicar. The amount in question came to around £15 a year. Cavendish pressed Gould for facts on the vicar’s turnip tithes, so that he could decide what “part of the turnips are tithable.” Cavendish wrote sternly to Gould for not having “explained the matter to me clearly.” Gould had given him his recommendations about the turnip tithes without at the same time giving him his “reasons.” Henceforth Gould was always to give Cavendish his “reasons.”117 Cavendish was not a miser; the money £15 was trifling. The matter of the vicar’s turnip tithes had to do with the way his mind worked: in making decisions about his estate, Cavendish needed “reasons.”

In its own good time, the Arnold affair came to a close. Following upon the petition, on 2 March 1789 the enclosure bill was ordered, setting in motion an elaborate parliamentary procedure, which was concluded with the royal assent on 13 July. With the exception of two proprietors, all of the parties gave their consent to the bill.118 For Cavendish, as no doubt for the other landowners, the news from Arnold would be bad before it was good again: in the summer of the following year, Gould told Cavendish that he had collected the rents from all but two of Cavendish’s tenants but he was not remitting them because the entire amount was expended in the Arnold enclosure.119

Cavendish’s early correspondence with his steward shows him to be new to the business. Once the farms were his responsibility, he set out to acquire a total familiarity with the facts of his estate, from which he reasoned on the basis of general principles, including the principle of justice, to conclusions about actions to take. In his approach to the management of his business, we recognize traits we have come to know in the natural philosopher.

Cavendish had a busy life in London with absorbing interests of his own choosing. From the questions he asked of his steward, we get the impression that he never visited his farms. He was burdened with landed property that was far away and that gave him trouble for a relatively small income he did not need. His steward sent him enclosure bills to study, and because he owned many properties, these bills repeatedly demanded his attention. With regard to an enclosure that had been pending for two years, Cavendish wrote to Gould: “You ought to have informed me of it at the time instead of delaying it till lately & then representing it to me as brought in by surprise & without your knowledge [.] I am very sorry to find that you could act in this manner & hope I shall never see another instance of any thing of the kind.”120 Cavendish suffered irritations like this because they came with his life and its responsibilities. If managing his estate brought no joy, we trust it brought satisfaction of a kind, the performance of a duty. No matter how far his activities in science took him away from his family, in his occupation with landed property he was with them

Places and Precision

The preceding sections have shown the importance of places in Cavendish’s life, and in other sections we have seen the importance to him of accuracy and precision.

Banks recommended a fellow of the Royal Society to head the English half of the project, William Roy

Believing that instruments of sufficient precision for the project did not yet exist, Roy said that it would be necessary to “reinvent them all.” Principal among them was a theodolite

On 16 April 1784 Cavendish, Banks, and Blagden met with Roy

From Hounslow Heath, triangles twelve to eighteen miles on a side were set out on a southward course to the coast, the terrain dictating a snake-like progression. The baseline was used for about half of one side of the first triangle. From then on, only angles were measured until the last triangle, which was measured by a second baseline of “verification,” laid out on Romney Marsh on the southern coast. To judge the “accuracy” of their operation in determining angles and sides, they found the “error” between the length of one base as computed from the other base and the length of the same base as measured on the ground to be within a few inches. The triangulation was, Roy said, “an instance of exactness as probably never occurred in any former operation of this sort.” From the English coast, observations were made to “intersect, with great accuracy

The second baseline had been measured with steel chains, which were easier to work with than glass rods, and which had been proven accurate on the first baseline. After Roy’s operation, there was some discussion of the error in measuring the two bases by different means, glass rods at Hounslow Heath and steel chains at Romney Marsh. On the principle that every base ought to be “measured twice at least,” in 1791 the baseline at Hounslow Heath was ordered re-measured using steel chains instead of glass rods. The new measurement differed from the original by less than three inches. The object by then was a general survey of Britain which was Roy’s goal, though he did not live to see it.126

Roy’s plan did not make use of the conspicuous landmark St. Paul’s Cathedral as a station of a triangle because he would have needed to make Hampstead and Harrow stations too, all three of which were inconvenient for what he called the “great instrument,” the theodolite. There were other problems with those stations too such as the “smoke of the Capital.” In fact, none of the stations Roy used were inside London, though from the stations outside, he could determine accurately the locations of St. Paul’s, Hampstead, Harrow, and many other places with steeples within the city. Independently of the Anglo-French project, from the baseline on Hounslow Heath in 1788 and 1789 Roy

Latitude 31° 27' 12.7”.

Longitude from Greenwich 0° 8' 39.2”. In time, 0h 0' 34.613”.

Bearing from the center of the dome of St. Paul’s, from south meridian westward 26° 29' 56.1”.

Distance in feet 24563.5.

Commenting on these numbers and those for several other places, Roy said that because he had the best instrument and a better way of measuring bases, the “relative geodetical situations of the stations […] may be said to be free from sensible error.”127 Knowing Cavendish’s desire for accuracy and precision, it is fitting that his principal home was a geodetic datum, angles expressed to a fraction of a second.

There was a problem. While preparing sheets of Roy’s final paper for the Philosophical Transactions, Blagden discovered numerical “blunders,” which he pointed out to Roy, who proceeded to find more on his own. Roy’s health was poor, and while he was absorbed in the heavy task of discovering and correcting his errors, on 1 July 1790 he died at his house in London. Roy took pride in his work as a military engineer, the aim of which was accuracy and precision,128 earning a solid reputation in a field that had no tolerance for careless error. He regarded the triangulation under his direction as “infallible, because, by means of the base of verification, it will prove itself.” The accuracy of it was a point of national and professional honor. Roy’s is a case of the gods striking down one they love.

There was concern that more errors lay hidden in the paper, which would be (triumphantly) discovered by the French commissioners of the project, especially by P.F.A. Méchain, who was bound to read the paper carefully. Had Roy’s errors been limited to the 1787 paper, they would not have been damaging, since it was only a sketch of the operation to come, but errors in the 1790 paper were another matter, since it was the final report, and the operation was an official undertaking of the Royal Society. Blagden turned for advice to one of the Society’s experts on errors. “Conversing a few days ago on this subject with Mr. Cavendish,” Blagden told Banks, “he suggested, that the best way of preventing any disgrace which might fall upon the Society on this account would be, to get the paper well examined here, and print such errors as might be discovered in the errata to the present volume of the Transactions, thereby anticipating, as far as possible, the remarks of foreigners.”129 Roy would have recommended the same course. At a time when the French triangulation had been criticized in Russia as “extremely erroneous,” Roy had expressed confidence that the Paris Academy of Sciences would, “no doubt, vindicate the credit of their own operation.”130 To vindicate its own, the Royal Society acted as Cavendish proposed. Roy’s assistant Isaac Dalby

The errors

Errors haunted Roy’s publication. In a paper the following year giving measures deduced from Roy’s triangulations, Dalby noted yet another error in the 1790 paper. Cavendish’s house on Clapham Common had been the corner of one of Roy’s secondary triangles, and its bearing from the dome of St. Paul’s was printed incorrectly. Dalby

In protecting the reputation of the Society, the reputation of Roy was protected as well; for what was valuable in his work was his observations, which were excellent.138 In 1784 he laid the foundation for the national survey, and in his papers of 1785, 1787, and 1790, he explained the methods for accurate triangulation. Cavendish headed the list of committee members appointed to examine Roy’s apparatus from the triangulation operation, which the king had donated to the Royal Society

Footnotes

Charles Cavendish to Thomas Revill, draft, 2 Mar. 1765, Devon. Coll., L/31/20.

7 Feb. 1783, Committee Minutes, British Museum, 7.

Devon. Coll., L/31/37.

Anonymous obituary of Charles Cavendish (1783).

Charles Cavendish’s will was probated on 28 May 1783. “Special Probate of the Last Will and Testament of the Right Honble Charles Cavendish Esq. Commonly Called Lord Charles Cavendish Deceased,” Devon. Coll., L/69/12.

“Walnut Cabinet in Bed Chamber,” “Papers in Walnut Cabinet,” and “List of Papers Classed,” Cavendish Mss Misc.

“The Honourable” followed by a given name and surname was allowed the sons of earls and the children of viscounts and barons. Other than for a duke, who was called “His Grace,” and a marquess, who was called “The Most Honourable,” the title “The Right Honourable” was given to all peers as a courtesy. The son of a peer, Charles Cavendish was called “The Right Honourable” or, more often, “Lord,” and occasionally “The Right Honourable Lord,” both parts of his title being by courtesy and proper. His son Henry was called “Honourable” by courtesy. Treasures from Chatsworth, The Devonshire Inheritance. A Loan Exhibition from the Devonshire Collection, by Permission of the Duke of Devonshire and the Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement, Organized and Circulated by the International Exhibits Foundation, 1979–1980, 24.

Charles Blagden to William Cullen, 17 June 1784, draft, Blagden Letterbook, Yale.

They were dinners on 1 and 8 May 1783. Minute Books of the Royal Society Club, Royal Society.

John Walker to James Edward Smith, 16 Mar. 1810, Smith (1832, 170–171).

12 June 1783, Paving Rate Books, Great Marlborough Street/Marlborough Mews, Westminster Archive, D 1260.

Cavendish first appears in the rate books on 3 Jan. 1782. “Hampstead Vestry. Poor Rate,” Holborn Public Library, London.

Alex J. Philip (1912, 45–46). F.M.L. Thompson (1974, 20–22, 24–26). Stabling could be had in the village, and coach service into London was convenient, there being between fourteen and eighteen return trips a day. Thomas J. Barrett (1912, 1:279–280). “Hampstead Vestry. Poor Rate.”

Cavendish Mss Misc.

Henry Cavendish, minutes of experiments on air, 15 and 16 Mar. 1782, Cavendish Mss II, 5:189.

We assume that this Edward Nairne was the instrument maker of that name. 17 Dec. 1782 and 15 Jan. 1783, Charles Blagden Diary, Royal Society, 1. Henry Cavendish to John Michell, 27 May 1783, draft; in Jungnickel and McCormmach (1999, 267–269). Cavendish had help with observations taken from the Hampstead church steeple, or he helped someone, as the angles are written in another hand, 23 and 25 July 1783. The unclassified papers in Cavendish’s scientific manuscripts contain a great many sheets of observations of bearings, with dates falling between 1770 and 1792.

William Cullen to Charles Blagden, 8 May 1784, Blagden Letters, Royal Society, C.70.

Charles Blagden to William Cullen, 17 June 1784, draft, Blagden Letterbook, Yale.

Charles Cullen to Charles Blagden, 7 Nov. 1784, Blagden Letters, Royal Society, C.62.

He asked for two or three months to remedy the defect, and if he failed he intended to resign. Charles Cullen to Charles Blagden, “Monday” [1784 or 1785], Blagden Letters, Royal Society, C.63. We assume that the following translation by Charles Cullen came out of his employment by Cavendish: Torbern Bergman, A Chemical Analysis of Wolfram, published in 1785. Cavendish was interested in wolfram, or tungsten.

“Henry Cavendish to Mr. Joshua Brookes. Counterpart Lease of a Messuage or Tenement with the Apperts No. in Marlborough Street in the Parish of St James Westminster County Middlesex,” 1788, Devon. Coll., L/38/35. London County Council, (1963, 256).

In his will, Charles Cavendish left his personal estate to Henry; he said nothing about his real estate. He named Henry as his sole executor. In Henry Cavendish, “List of Papers Classed,” under “Mine,” there is an entry “agreement about house in M.S.,” no doubt “Marlborough Street,” where his father’s house was. We have not found that agreement. Charles Cavendish’s will, signed 1 August 1756, probated 28 May 1783, Devon. Coll., Chatsworth, L/69/12.

John Cavendish to Henry Cavendish, 25 Aug. 1785. Henry Cavendish to John Cavendish, n.d., draft, Devon. Coll.

Bedford Estate Archive, NMR 16/21/3. We were misled by the rate books in the first edition of this book. Jungnickel and McCormmach (1999, 315).

Middlesex Deed Register, MDR/1784/2/353.

Charles Blagden to John Blagden Hale, n.d., draft, Blagden Letterbook, Yale. In this letter Blagden told his brother that he was moving to Gower St. at the end of next week. He said that he watched Blanchard’s balloon on the day he wrote the letter, which dates it, 16 Oct. or 30 Nov. 1784.

London County Council (1914, 150). Anon., “Bloomsbury Squares & Gardens. Bedford Square” (http://bloomsburysquares.wordpress.com/bedford-square).

“J. Willcock’s Valuation of House & Stables in Bedford Square,” 30 Dec. 1813, Devon. Coll.

Ibid.

“6 Sept. 1810. Mr Paynes Valuation of Books £7000”; “29 April &c. 1814 Account Respecting the Sale of a Leasehold House at the North East Corner of Bedford Square,” Devon. Coll.

“Inventory of Sundry Fixtures, Household Furniture, Plate, Linen, the Property of the Late Henry Cavendish Esquire at His Late Residence in Bedford Square. Taken the 2nd Day of April 1810,” Devon. Coll., 114/74. The Particulars of a Capital Leasehold House, and Offices Situate at the North East Corner of Bedford Square… Sold by Auction, by Mr. Willcock on Friday the Twenty-ninth of April, 1814, Devon. Coll. There were in addition to the five family portraits in the house ten damaged ones in the lumber room over the stables.

24 June 1773, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 6:177–178.

Wilson (1851, 163), cites Cavendish’s early biographers Cuvier and Biot on Cavendish’s library. All that Biot says is that Cavendish located his library two leagues, or five English miles, from his residence so as not to be disturbed by readers consulting it. Five miles is roughly the distance from Clapham, the location of Cavendish’s country house, to the center of London. Since neither Biot nor Cuvier mentions Dean Street, Wilson supplied this address from unknown sources. Georges Cuvier (1961, 237); J.B. Biot (1813, 273).

Dean Street entries turn up intermittently through the assessment of the poor rates; entries for the years 1783, 1785, 1790, 1795 contain no reference to Cavendish. From 1781 the rate books were split between the wards of King Square, West, and Leicester Fields, West. Westminster Record Office.

Charles Blagden to Joseph Banks, 15 and 30 Sep. 1785, Banks Correspondence, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew 1:204 and 207.

Charles Blagden to Lorenz Crell, 7 June 1787, draft, Blagden Letters, Royal Society 7:60.

Charles Blagden to Henry Cavendish, 23 Sep. 1787, in Jungnickel and McCormmach (1999, 641–644). Cavendish read printed German but clearly not German script.

17 Apr. 1788 and 24 Dec. 1789, JB, Royal Society 33.

Thomas Young (1816–1824, 435–447, on 445).

“Collingwood, the Librarian, One Years Salary Due Xtmas 1811” in “29th May 1812. Taxes &c. for House in Bedford Square,” Devon. Coll.

Charles Blagden to Thomas Beddoes, 12 Mar. 1788, draft, Blagden Letters, Royal Society 7:129.

Pahin de la Blancherie to Henry Cavendish, 23 Sep. 1794; in Jungnickel and McCormmach (1999, 697–698).

La Blancherie having found that where he was living Newton once had lived tried to capitalize on it. Three years before he complained to Cavendish, he published a grandiose plan for honoring Newton. Cavendish probably did not like it. There was also a question of his methods of journalism. Blagden believed that he was a victim of the “worst kind of indiscretion” on La Blancherie’s part. Charles Blagden to La Blancherie, 21 May and 23 Aug. 1785, drafts, Blagden Letterbook, Yale.

Wilson (1851, 174). The librarian was probably not the German. Thomas Young said that after the German librarian died, Cavendish himself checked out the books, and if that is correct the German librarian did not leave to live in the country.

Historical Notice by J.P. Lacaita, July 1879, Catalog of the Library at Chatsworth, 4 vols. (London, 1879) 1:xvii.

Listed as “Cavendish Tract. Draft Catalog 1966.”

Part I of the catalog of Dalrymple’s library contains 7190 entries. Part II, containing books on navigation and travel, his specialty, might be even longer. A Catalog of the Extensive and Valuable Library of Books; Part I. Late the Property of Alex. Dalrymple, Esq. F.R.S. (Deceased). Hydrographer to the Board of Admiralty, and the Hon. East India Company, Which Will Be Sold by Auction, by Messrs. King & Lochée … On Monday, May 29, 1809, and Twenty-three Following Days, at Twelve O’ Clock (London, 1809).

Ellen B. Wells (1983, 338, 354, 362, 370).

Harvey (1980) has tallied books in Cavendish’s catalog by subject according to whether they were published before or after 1752, the year Henry finished his university education. The results are not very meaningful in the way they are intended. A more useful division for distinguishing Henry Cavendish’s interest from his father’s is 1783, when Lord Charles Cavendish died.

Cálidás, Sacontula, or the Fatal Ring, an Indian Drama (London, 1790). Not entered in the catalog, because it was too late, under poetry and plays but found in the Chatsworth library, with Henry Cavendish’s stamp, is the related work, The Loves of Cámarúpa and Cámalutà, an Ancient Indian Tale, trans. W. Franklin (London, 1793).

Boswell’s Life is listed under “History” in Cavendish’s catalog. Boswell dined at the Royal Society Club twice in 1772, both times with Cavendish in attendance. Archibald Geikie (1917, 118).

Gowin Knight (1748, 11–12).

Daniel Lysons (1795, 159–161). In the legal documents, the land Cavendish bought is said to be fifteen acres, not fourteen (it is in between). Historically, Clapham Common was common land for two parishes, Clapham and Battersea. Anon., “Clapham Common” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clapham_Common).

Map of Clapham Common, with names of all of the residents. “Perambulation of Clapham Common, in 1800. From C. Smith’s ’Actual Survey on the Road from London to Brighthelmston,’” in J.H. Michael Burgess (1929, 112). Reproduced by permission of the Bodleian Library.

Christopher Baldwin to Henry Cavendish, 15 June 1784, Devon. Coll., 86/comp. 1.

Christopher Baldwin to Henry Cavendish, 3 May 1784, ibid.

Henry Cavendish to Christopher Baldwin, n.d. [After 3 May and 2 June 1784], drafts; Christopher Baldwin to Henry Cavendish, 2 and 7 June, 3 July 1784, ibid.

The history of Cavendish’s Clapham Common estate is told in a bulky document at Chatsworth, a title search in 1827, beginning with the bargain of sale between Baldwin and Cavendish on 2 November 1784. When Henry Cavendish died, his Clapham Common estate was left to his brother Frederick. When Frederick died two years later his will, which was unchanged, left his real property to Henry. In 1827, Frederick’s heir at law William Spencer Cavendish, 6th duke of Devonshire sold the estate. “Abstract of the Title of His Grace the Duke of Devonshire to an Estate at Clapham Common in the County of Surrey,” Devon. Coll. 38/78.

“Statement of Leases by the Honourable Henry Cavendish of Messuages and Lands at Clapham in Surrey,” 1795–1805, Devon. Coll., 34/10. “Henry Cavendish Esquire and Messrs Hanscomb, Fothergill and Poynder. Articles of Agreement for a Building Lease,” 1791, ibid., L/31/45. “Abstract of the Title of His Grace the Duke of Devonshire to the Estate at Clapham Common in the County of Surrey, “ibid., L/38/78. The builders each paid £200 per year rent to Cavendish.

Henry Cavendish to Christopher Baldwin, n.d. [After 3 May 1784], draft, Devon. Coll., 86/comp 1. Mrs. Mount’s house is referred to in Henry Cavendish, “Plan of Drains at Clapham & Measures Relating to Bason,” Cavendish Mss Misc.

Baldwin to Cavendish, 3 May 1784.

In favor of this alternative might be his interest in buying Mount’s house while he was negotiating with Baldwin about buying the fifteen acres. Also Thomas Hanscomb who dealt with Baldwin as Cavendish’s agent would build houses for Cavendish on the fifteen acres.

Surrey Deeds (Index), Lambeth Archives, 14.171.

Before Cavendish’s arrival on the Common, a scientific experiment had been performed on Mount Pond by Cavendish’s colleague in electricity Benjamin Franklin, who was at the time staying with Christopher Baldwin. Brown’s will is in the National Archives, PROB 11/1011/362. Clapham Antiquarian Society, “Cavendish House.” Michael Green, “Mount Pond, Clapham Common: Archaeology and History,” The Clapham Society Local History Series 7 (http://www.claphamsociety.com/Articles/article7.html).

In our biography Cavendish (1999), we said that Cavendish rented his house on Clapham Common. We correct ourselves here: Cavendish bought a lease for the house. I am grateful to Colin Thom for clarifying the purchase.

There is a document at Chatsworth that we originally thought applied to the house Cavendish bought at Clapham Common, which if so would give us an idea of the number of rooms in the house and their description. Jungnickel and McCormmach (1999, 326). The inventory is a room-by-room list of bookcases, curtains, stoves, and other fixtures, which were to be valued to the person who bought the estate. Mr. and Mrs. E. Collinson had lived in the house, and the fixtures belonged to Mr. Collinson and Mr. Tritton of Clapham. The name Tritton suggests a connection to Cavendish’s house: Anna Maria Brown, daughter of Henton Brown, thought to be the first owner of Cavendish’s house, married Thomas Tritton (1717–86); she lived on Clapham Common. The year of the inventory was 1732. In pencil, Cavendish located each room in the house: “west wing back,” etc. This inventory is pinned to another inventory of fixtures Cavendish bought from the seller of his house on Clapham Common, William Robertson. The items in the two inventories are different. The earlier inventory was of fixtures in another large house at Clapham, not of the one Cavendish bought, as we first supposed. There is no explanation why Cavendish annotated the inventory and why he kept it with papers about purchases for his house. The puzzling document is “An Inventory of Fixtures Belonging to Messr Collinson and Tritton of Clapham in Surrey to be Valued to the Purchaser of the Estate May 13th, 1732.” It is pinned to “An Inventory of Fixtures in the House Purchased by Mr.Cavendish of Mr Robertson.” A related document is “Sundry Drawing Room Furniture of Wm. Robertson’s Esqr Appraised to Cavendish Esqr. 11th June 1785.” The general heading is “About Purchase of House & Furn. at Clapham.” Devon. Coll., 86/comp. 1. “Anna Maria Brown,” “The Peerage.”

Edwards, Companion, 11.

Henry Cavendish to Joseph Priestley, 20 Dec. 1784, draft, in Jungnickel and McCormmach (1999, 598–599). In 1784, Cavendish would have been moving into his new house on Bedford Square.

Charles Blagden to William Lewis, 20 June 1785, draft, Blagden Letter book, Yale.

Charles Blagden to Pierre Simon Laplace, 16 Nov. 1785, draft, Blagden Letters, Royal Society 7:733.

Ibid.

In the executor’s accounts, the instrument maker William Harrison is listed with the servants, but in Cavendish’s will he is mentioned separately from the servants. Copy of the will, Devon. Coll., L/31/65.

“Extracts from Valuation of Furniture,” Devon. Coll.

Ibid.

Christopher Baldwin to Henry Cavendish, 7 July, 19 Sep. 1785; Henry Cavendish to Christopher Baldwin, [July 1785], draft; Thomas Dunn to Henry Cavendish, 6 Sep. 1785, Devon. Coll., 86/comp. 1.

Thomas Dunn to Henry Cavendish, 6 Feb. 1786; Christopher Baldwin to Henry Cavendish, 22 and 27 Feb. 1786; Henry Cavendish to Christopher Baldwin, n.d. [After 22 Feb. 1786], draft, and n.d. [after 27 Feb. 1786], draft, ibid.

Christopher Baldwin to Henry Cavendish, Midsummer’s Day, 1784, ibid.

Christopher Baldwin to Henry Cavendish, 8 Feb. [1786]; Henry Cavendish to Christopher Baldwin, n.d. [on or after 8 Feb. 1786], draft, ibid.

Christopher Baldwin to Henry Cavendish, 3 Mar. 1786, Saturday [1 Apr. 1786], Saturday [1 Apr. 1786]; Henry Cavendish to Christopher Baldwin, 1 Apr. [1786], n.d. [1 April 1786], drafts, ibid.

Baldwin deeded to Cavendish the one half acre of land “abutting or bounding” Balam Lane. On the same day he released all claims on the fifteen acres he sold to Cavendish, for a consideration of £80. Christopher Baldwin to Henry Cavendish, 5 Apr. 1786, “Lease” for the one half acre. Christopher Baldwin to Henry Cavendish, 6 Apr. 1786, “Release of a Piece of Land on Clapham Common.” Christopher Baldwin to Henry Cavendish, “General Release,” for a consideration of £80. Devon. Coll., 38/78.

Charles Cavendish to Thomas Revill, 5 Sep. and 13 Dec. 1764, draft, Devon. Coll., L/31/20.

Charles Cavendish to Thomas Revill, 19 Sep. and 3 Dec. 1776, 12 Apr. 1777, 18 Mar. 1778, drafts; Thomas Revill to Charles Cavendish, 31 Jan. 1765, Devon. Coll., L/31/20 and 34/5.

Henry Cavendish to William Gould, 30 Dec. 1782, draft, Devon. Coll., L/34/7.

Thomas Revill to Charles Cavendish, 16 Dec. 1764, Devon. Coll., L/31/20.

William Gould to J.W. Heaton, 10 June 1782. Heaton forwarded this letter to Cavendish, adding his recommendation of Gould. Henry Cavendish to William Gould, 8 and 9 Aug. 1782, drafts, Devon. Coll., L/34/7.

Henry Cavendish to Thomas Revill, 16 and 28 Aug. and 5 Sep. 1782, drafts; Henry Cavendish to William Gould, 6 Sep. 1782, draft, Devon. Coll., L/34/7.

For example, Cavendish received rent from the tithes of Marston in Derbyshire, the greater part of which parish was owned by the duke of Devonshire. William Gould to Henry Cavendish, 28 Sep. 1782, Devon. Coll., L/34/7.

Henry Cavendish to William Gould, 2 Dec. 1787, draft, Devon. Coll., L/34/7.

William Gould to Henry Cavendish, 20 Aug. 1785; Arundall Gallway to Henry Cavendish, 21 Aug. 1785; Pemberton Milnes to John Cavendish, 24 Aug. 1785; John Cavendish to Henry Cavendish, 25 Aug. [1785]; Henry Cavendish to John Cavendish, n.d. [reply to letter of 25 Aug. 1785], draft, Devon. Coll., L/34/7.

Charles Cavendish to Thomas Revill, 8 [9] Dec. 1776, draft, Devon. Coll., L/34/5.

William Gould to Henry Cavendish, 25 Mar. 1784, Devon. Coll., L/34/7. Chambers (1966, 78, 199–200).

Charles Cavendish to Thomas Revill, 3 and 12 Dec. 1776, drafts, Devon. Coll., L/34/5.

Gould forwarded the petition from Arnold in a letter to Cavendish, 28 Sep. 1782.

William Gould to Henry Cavendish, 24 Nov. 1784, Devon. Coll., L/34/7.

Henry Cavendish to William Gould, Dec. and 24 Dec. 1784, drafts, Devon. Coll., L/34/7.

Henry Cavendish to W. Sherbrooke, 6 Jan. 1785, draft; W. Sherbrooke to Henry Cavendish, 3 and 18 Feb. 1785. Cavendish also received an anonymous letter from a landholder in Arnold complaining of Gould, Mar. 1785, Devon. Coll., L/34/7.

Henry Cavendish to William Gould, 23 Feb. 1785 and n.d. [after 28 Feb.] 1785, drafts; Henry Cavendish to W. Sherbrooke, 16 Feb. 1785, draft, Devon. Coll., L/34/7.

Cavendish to Gould, 2 December 1787.

Henry Cavendish to William Gould, n.d [reply to letter of 21 Feb. 1789], draft, Devon. Coll., L/34/12. William Gould to Henry Cavendish, 19 Mar. 1789.

William Gould to Henry Cavendish, 30 Mar. 1789, Devon. Coll., L/34/12. 2 Mar., 13 May, and 12 June 1789, Journal of the House of Commons 44:138, 361, 454, and 456.

William Gould to Henry Cavendish, 5 June 1790, Devon. Coll., L/34/12.

Henry Cavendish to William Gould, 12 May 1789, draft, Devon. Coll., L/34/12. Gould defended himself against Cavendish’s “severe reprimand” and gave his reasons. William Gould to Henry Cavendish, 20 May 1789, Devon. Coll., L/34/12.

29 June 1787, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 7:276. William Roy (1787, 213–214; 1785, 389). Charles Coulston Gillispie (1980, 122–123). In 1784, the elder Cassini died, succeeded as director-general of the Paris Observatory by his son Jean-Dominique Cassini, who was appointed by the Paris Academy of Sciences to superintend the French half of the project. He renovated the Observatory, procured new instruments, and oversaw the joint Anglo-French operations.

William Roy (1790, 116, 121, 133; 1785, 391, 394, 425, 430, 441). O’Donoghue (1977, 46).

Roy requested a British commissioner to join the French commissioners in making measurements across the Straits of Dover, proposing Blagden, who was appointed by the Council of the Royal Society. O’Donoghue (1977, 1, 41). Joseph Banks to Charles Blagden, 13 Oct. 1783, Blagden Letters, Royal Society, B.19. Charles Blagden to Joseph Banks, 12 July 1784 and “Tuesday” [1784], Banks Correspondence, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 167, 171. Charles Blagden to Henry Cavendish, 16 Sep. 1787; in Jungnickel and McCormmach (1999, 634–635). Henry Cavendish to Charles Blagden, [after 16 Sep.1787], draft; ibid., 638–640. Charles Blagden to Benjamin Thompson, 27 May 1787, draft, Blagden Letters, Royal Society 7:55. Charles Blagden to Dr. William Watson, 22 Aug. 1787, ibid. 7:347.

Edward Williams, William Mudge, and Isaac Dalby (1795, 417–418). O’Donoghue (1977, 1, 42).

Roy (1790, 260–261).

Charles Blagden to Joseph Banks, draft, 31 Aug. 1790, BL Add Mss 33272.

Roy, “Account of the Mode Proposed,” 211.

Blagden to Banks, 26 Sep. 1790.

Charles Blagden, “Appendix,” to Roy (1790). Isaac Dalby, “Remarks on Major-General Roy’s Account of the Trigonometrical Operation, from Page 111 to Page 270 of This Volume,” ibid., 593–614.

Charles Blagden, “Appendix,” to Roy (1790). Blagden’s and Dalby’s appendices were printed at the end of volume 80 of Philosophical Transactions.

William Roy (1777, 653–654).

Dalby, “Remarks on Major-General Roy’s Account,” 614.

Roy’s errors were unimportant relative to his observations, according to John Playfair in his review of William Mudge’s collection of memoirs on the triangulation begun by Roy. Playfair (1822, 4:198–201).

11 Nov. 1790, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 7:232–234.