Charles Blagden

Around the time of his father’s death, Henry Cavendish acquired a helper, Charles Blagden (Fig. 12.1). Wilson called Blagden Cavendish’s “assistant,”1 which he was, but his part in Cavendish’s affairs was more extensive than what what we normally think of as an assistant’s. He was a professional man, a physician, and a scientific colleague, and he was also a confidant, who knew personal things about Cavendish such as his income and the terms of his will. For these reasons and to distinguish him from the young men Cavendish occasionally hired to assist him, we speak of him as Cavendish’s “associate.” His relationship to Cavendish being unique, he holds our attention for what he can tell us about our subject.

A man of modest means and talent, unlike Cavendish in both respects, Blagden made for himself a suitable place in science. Born in 1748 in a village in Gloucestershire, he studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh, where he received a good introduction to science from lecturers who included William Cullen

In 1768 Blagden graduated with an M.D. The following year he was informed of an “immediate opening for a physician at Gloucester” created by the departure of one of the two physicians at the infirmary. In this way, he began his life as a physician close to where he grew up.3 His correspondence from the time tells of his interest in acquiring scientific instruments. A London friend ordered for him an electrical machine from Ramsden, which he may have used on his patients, and a microscope with a lens made by the optical instrument maker Peter Dolland.4 He was interested in learning foreign languages

In London Blagden

Wilson and the author of a biographical article on Blagden said that it is unknown how Blagden became acquainted with Cavendish, how he came to work with him in 1782, and why they parted in 1789.9 While we cannot answer these questions completely, we have a fair idea. Blagden met Cavendish at the Royal Society Club, where he dined as a guest several times in the fall and winter of 1773, and again several times in 1774 and 1775.10 The first documented scientific connection between Blagden and Cavendish came about in the year of Blagden’s last experiments in a heated room, 1775. The war with the American Colonies had begun, and Blagden was scheduled to go to North America as an army surgeon. Cavendish advised him to compare the temperature of the air with the temperature of the sea on his journey

In North America, Blagden

While Blagden was in North America, Cavendish was on his mind; he wrote to Banks, who was then president of the Royal Society, asking why Cavendish was left off the Council in 1778.16 Soon after his return, on March 9, 1782, Blagden had breakfast at Cavendish’s house, the first mention in his diary of a visit.17 He was still a regimental surgeon,18 and in June he was called back to Plymouth.19 In July he wrote to Banks that he would like to “live as much as I can among books,” wondering if the Royal Society would make a position for him such as “Inspector of the Library, or something of that sort,” with apartments next to the Royal Society’s in Somerset House. He would be willing to pay or to superintend the library in exchange, but Banks told him it was not possible to use the apartments for any purpose other than what they were meant for.20 In November he wrote to Banks that he endured the “miserable exile here only with the hope of soon returning to your society, in which all the comfort of my life is centered.”21 Two weeks later he was back in London; he would not return to Plymouth.

As he had promised Cavendish before he left for war, Blagden bottled air in Plymouth in all kinds of weather. In his diary for 28 November 1782, he noted that he assisted Cavendish in testing the bottled air with a eudiometer

In May 1783, Blagden went on half pay as an army physician.28 In June and July, he visited Paris for the first time, noticing things that catch a visitor’s eye such as people walking on dirty streets wearing their hair highly dressed. More important, he dined with Lavoisier, who showed him experiments.29 Blagden’s papers contain a list of people to meet in Paris, who included Laplace, Lagrange, Coulomb, and Berthollet. Without knowing it, he was preparing himself for the role he would play as a conveyor of scientific information between England and France.

After Blagden had declined Phipps’s offer to help him in his medical career, a similar opportunity came up in In October 1783, this one definite and remunerative. Heberden

Two days after informing Banks

At the time that Blagden

During the time he acted as Cavendish’s associate, and because of it, he became involved in a controversy over the discovery of the composition of water

Samuel Johnson called Blagden

Blagden’s

Blagden’s association with a rich aristocrat was grist for rumor mills. The chemist Richard Kirwan wrote to a French colleague that Blagden looked at questions in science only through Cavendish’s eyes because Cavendish “is a near relation of the duke of Devonshire and has six thousand pounds yearly income.”50 Blagden’s critics said he was avaricious. According to Henry Brougham, Blagden wished to marry the widow of Lavoisier for her wealth. Jomard, however, described him as liberal with money.51 “Frugal” better describes Blagden. At the time of his death, his estate was valued at around £50,000,52 an amount which had ceased to be a large fortune in the eighteenth century, though with it Blagden could have lived quite comfortably

In the fall of 1784 Blagden exchanged his lodgings off Great Ormond Street for a rental house across the street from Cavendish’s, No. 7 Gower Street, Bedford Square

Just after you were gone Mr Hanscombe called here with the inclosed note, & opened it; he had [—–] before at your house, but having been informed you were gone by to Hampstead came to shew it to me. I am extremely obliged to you for the liberal offer you have made; but as, were I so rich that the sum would be no object to me I should still think it too much for the house, & shd probably refuse to give it. I cannot but consider it as totally inequitable that you shd give it for me. I therefore do most seriously request that you would refuse to comply with the terms proposed, & wait till an opportunity offers of making a fairer purchase; and in the mean time I will use every means in my power to become reconciled to my present situation.55

Blagden

It is thought that Cavendish and Blagden ended their association in 1789. Thomson

Blagden considered living abroad for the winter 1789–90 in part because it might “prevent an open rupture with Sir Jos. Banks.” He asked Cavendish if his absence would hold up any work of his that Blagden was unaware of. “Now I trust to the strict principles of <openness> sincerity by which I know you are always guided “that you will fairly tell me” for an open & explicit answer to the question whether you have on your own part any objection to my going.”59 These are not words of someone who is breaking off a relationship. Cavendish’s only concern about Blagden’s going was that it might interfere with the pursuit that Blagden had “much more at heart than any object in life,” which Cavendish understood to be the practice of medicine

Clubs

The setting of Henry Cavendish’s social life was clubs

Named after the day of the week it met, the Monday Club

Colleagues

Fig. 12.1: Sir Charles Blagden

Fig. 12.2: Alexander Dalrymple. Engraving by Rudley from a drawing by John Brown. Frontispiece to European Magazine 42 (November 1802).

Fig. 12.3: Engraving by J. Chapman, painting by S. Drummond. Wikipedia.

Fig. 12.4: Engraving by J. Mitan from the portrait by G. Slous. Wikimedia Commons.

Fig. 12.5: Nevil Maskelyne. Coloured stipple engraving by R. Page, 1815. Wellcome Library, London.

Fig. 12.6: Sir William Herschel. Painting by Lemuel Francis Abbott, 1785. Wikimedia Commons.

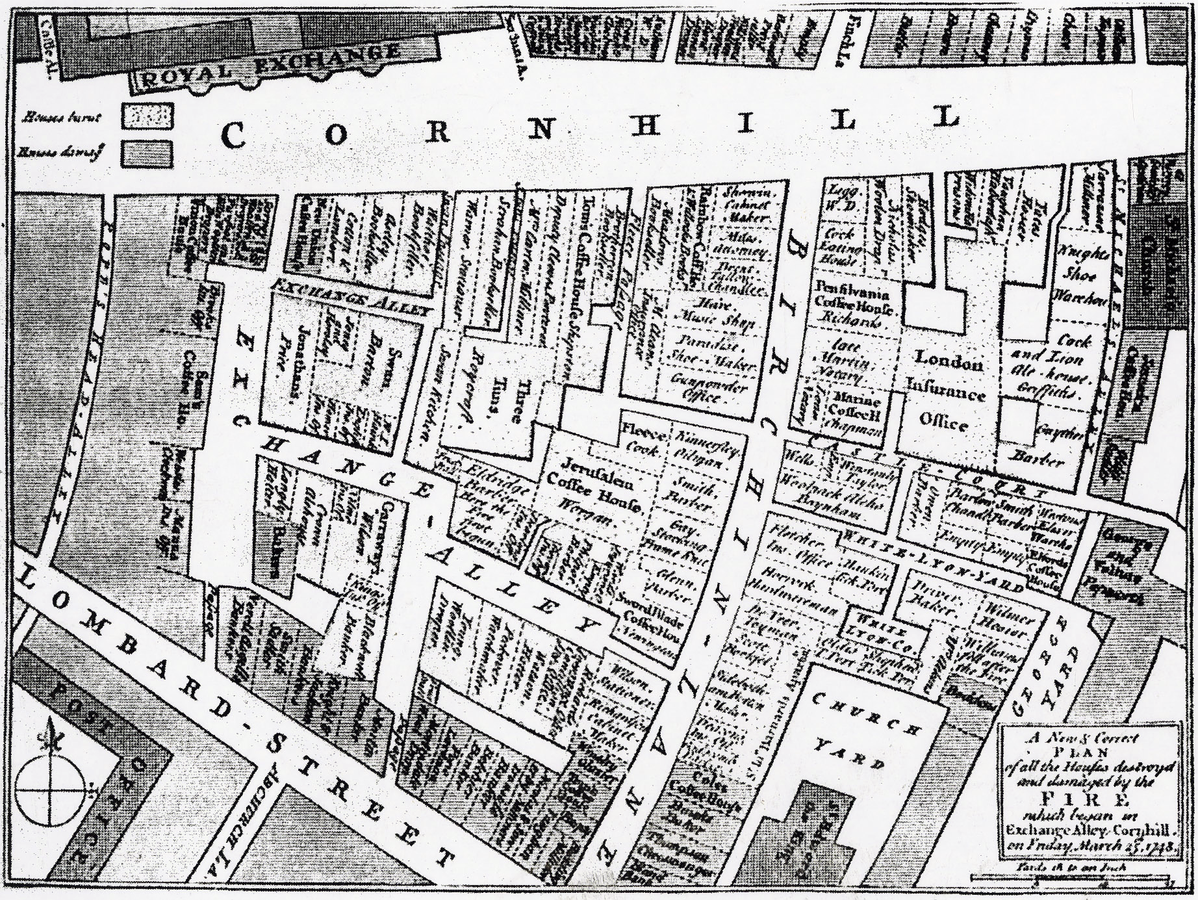

Fig. 12.7: Map of Cornhill. The map shows the buildings damaged or destroyed by a fire originating in Exchange Alley in 1748. A good number of coffee shops relocated but not the George & Vulture off George Yard, shown at the upper right corner of the map. Cavendish met his colleagues there on Monday evenings. Aytoun Ellis (1956, 94).

Footnotes

William Cullen to William Hunter, 11 Feb. 1769, in John Thompson (1859, 555–556).

Henry Cumming to Charles Blagden, 7 Nov. 1769, Blagden Letters, Royal Society, C.72. J. Smart to Charles Blagden, 22 Sep. 1769, ibid., S.11.

Jesse Ramsden to Charles Blagden, 23 Nov. 1769, ibid., R.40.

Henry Cumming to Charles Blagden, 26 Mar. 1767. Thomas Curtis to Charles Blagden, 26 Dec. 1769, 7 Jan., 8 Feb. 1770, ibid., C.77–79.

Thomas Curtis to Charles Blagden, 15 Jan. 1770, ibid., C.78.

J. Smart to Charles Blagden, 24 Feb. 1772, ibid., S.16.

Charles Blagden (1775a, 112, 119, 122; 1775b, 493).

Wilson (1851, 128–29). Frederick H. Getman (1937, 70–71).

He was elected to the Club in 1780. Geikie (1917, 122, 125, 127, 148).

Charles Blagden (1781, 334, 341–44). A more complete statement of Cavendish’s part in this discovery is in the draft of a paper in Blagden Papers, Yale, box 2, folder 26.

Charles Blagden Diary, 1776–1779, Yale

Charles Blagden to Joseph Banks, 12 June 1778, 20 Oct. 1778, Natural History Museum, Botany Library, Dawson Turner Collection 1:191–192, 228–229. Hereafter BM(NH), DTC.

Charles Blagden to Joseph Banks, [21 June 1780], ibid. 1:290–291.

C.J. Phipps, Lord Mulgrave to Charles Blagden, 1 Mar. 1780, Blagden Letters, Royal Society, B.35.

Charles Blagden to Joseph Banks, 2 Mar. 1778, BM(NH), DTC 3:184–185, on 184.

9 Mar. 1782, Charles Blagden Diary, Royal Society, 1.

15 May, 14 Aug. 1782, Charles Blagden Diary, Royal Society, 1.

Charles Blagden to Joseph Banks, 30 June, 3 Nov. 1782, BM(NH), DTC, 2:147–150, 205–206.

Charles Blagden to Joseph Banks, 19 July 1782, draft; Joseph Banks to Charles Blagden, 19 Aug. 1782, Blagden Letters, Royal Society, B.8a and 9.

Charles Blagden to Joseph Banks, 3 Nov. 1782, BM(NH), DTC 3:205–206, on 205.

Blagden to Banks, 3 Nov. 1782. Entry for 28 Nov. 1782, Charles Blagden Diary, Royal Society, 1.

17 Dec. 1782, Charles Blagden Diary, Royal Society, 1.

23 Dec. 1782, ibid. An ahistorical translation of this statement is: oxygen is only water deprived of hydrogen.

21 Jan. 1783, Charles Blagden Diary, Royal Society, 1.

25 Feb. 1783 and following entries, ibid.

For the 1780s: Minute Book of the Royal Society Club, Royal Society, 7.

Letter from the war office: FitzPatrick to Charles Blagden, 7 May 1783, Blagden Letters, Royal Society, F.10.

7 June 1783, Charles Blagden’s diary of his travels in France in 1783, Blagden Papers, Yale, box 1, folder 3.

William Heberden to Charles Blagden, 7 Oct. 1783, Blagden Letters, Royal Society, H.23. Charles Blagden to William Heberden, 8 Oct. 1783, ibid., H.23.a. These two letters are also published in Ernest Heberden (1985, 185).

Charles Blagden to Joseph Banks, 16 Oct. 1783, BM (NH), DTC 3:127–131, on 127.

Joseph Banks to Charles Blagden, 18 Oct. 1783, Blagden Letters, Royal Society, B.21.

James Boswell (1821, 4:309).

Charles Blagden to Benjamin Thompson, 7 Feb. 1786, draft, Blagden Letterbook, Yale.

Ibid., 135.

Ibid., 132.

Wilson’s sources were Robert Brown and Mr. Caddell. Ibid.

Sylvester Douglas, Lord Glenbervie, F.R.S., in his Diaries (London, 1928), quoted in G.R. De Beer (1950, 76).

Joseph Banks to Charles Blagden, 28 July and 4 Aug. 1785, Blagden Letters, Royal Society, B.35 and 36.

Lord Castlereagh to Charles Stuart, 13 July 1819, copy, Blagden Letters, Royal Society, C.6.

Cavendish’s involvement in Blagden’s scientific work is documented in Blagden’s publications and in his manuscripts, which contain pages written in Cavendish’s hand. In counting ten papers in the journal by Blagden, two papers are omitted: an extract from a letter by Blagden on the tides at Naples in 1793, and an appendix to Ware’s paper on vision in 1813.

Blagden developed a simple quantitative relation, the lowering of the freezing temperature of a solution is proportion to the quantity of solute, known to this day as “Blagden’s Law.”

A £500 annuity was mentioned by Blagden’s brother John Blagden Hale, Thomas Thomson, and Henry Brougham. The latter said that Cavendish insisted that Blagden abandon his practice of medicine. Wilson (1851, 133, 142, 160).

Gloucestershire Record Office, D1086, F156.

Charles Blagden to Joseph Banks, 8 Apr. 1790, draft, BL Add Mss 33272.

Richard Kirwan to Guyton de Morveau, 9 Jan. 1786, in Guyton de Morveau (1994, 161–164, on 163).

Ibid., 74.

Charles Blagden to Mr. Mountfort, 22 Mar. 1785, draft, Blagden Letterbook, Yale.

In 1786 the rate books list Blagden at both of his addresses on Gower Street; for that year the ratable value of his first house was £32 and of his second house £65; Cavendish’s house was valued at £120. Rate Books for Gower Street: Bloomsbury Division (part 1), 11; St. Giles in the Fields Division (part 2), 23, 25. For 1789: St. Giles in the Fields Division (part 2), 31–32. Camden Archives.

Blagden Collection, Royal Society, Misc. Matter – Unclassified.

Hanscomb & Fothergill, “Carpenters Work Done for Dr Blagden at His House at Clapham,” Gloucestershire Record Office, D 1086, F153.

Blagden Collection, Royal Society, Misc. Notes, 224.

Thomas Thomson (1830–1831, 1:338).

Blagden to Cavendish, Aug. 1789.

Charles Blagden to Henry Cavendish, Aug. 1789, draft; in Jungnickel and McCormmach (1999, 666–667).

As the experiment would take the better part of the day, they were to arrive by 10 AM, and if they arrived by 9 AM they could join Cavendish at breakfast. Charles Blagden to Edward Nairne, 5 Oct. 1790, draft, Blagden Letters, Royal Society 7:457. Charles Blagden to Henry Cavendish, 5 Oct. 1790, draft; in Jungnickel and McCormmach (1999, 679).

Charles Blagden to Joseph Banks, 17 Oct. 1790, BL Add Mss 33272, 91–92.

1 Mar. 1810, Charles Blagden Diary, Royal Society 5:428(back).

A.E. Musson and E. Robinson (1969, 58). Bryant Lillywhite (1963, 22–24).

From the 1730s, there is a record of a meeting that included a number of scientific men at a King’s Head. R. Parkinson (1854–1857, vol. 1, pt. 2, 556). Seven King’s Head taverns are listed under the signs of taverns in Vade Mecum, included in Walter Besant (1902, 639–640).

William Watson to Benjamin Franklin, 31 July 1772, in Wilcox (1969/1974, 213).

Henry B. Wheatley (1891, 2:484). Lillywhite (1963, 404).

John Strange to Joseph Banks, 8 Aug. 1788, Banks Correspondence, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, l.315.

Lillywhite (1963, 160, 201, 699, 792).

1 Jan. 1782, Charles Blagden Diary, Royal Society, 1.

On Franklin and Aubert: Crane (1966, 213). On Dalrymple: 15 June 1795, Charles Blagden Diary, Royal Society 3:62 and elsewhere. On Phipps, Nairne, and Smeaton: Alexander Aubert to Joseph Banks, 1 July 1789, BL Add Mss 33978, no. 251.

Alexander Aubert to William Herschel, 7 Sep. 1782, Herschel Mss, Royal Astronomical Society, W 1/13, A 10. Aubert to Banks, 1 July 1789.

25 Aug. 1794, Charles Blagden Diary, Royal Society 3:13.