Lise Meitner Looks Back

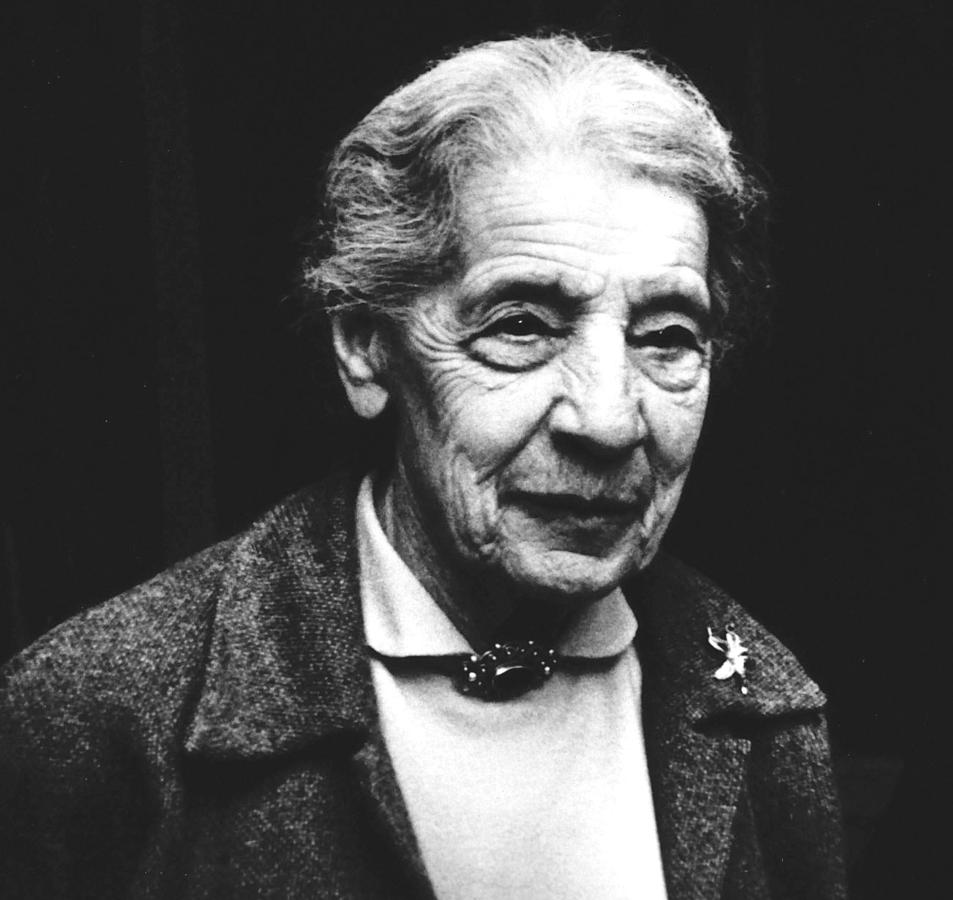

Abb. 1: Lise Meitner in 1963; portrait taken by Lotte Meitner-Graf. (© Archiv der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Berlin-Dahlem)

In 1963, at the age of nearly 85, Lise Meitner gave a talk at the Urania in Vienna. It was titled “50 Jahre Physik” (“Memories of Fifty Years in Physics”) and published the following year in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists as “Looking Back.” In print the article is only six pages long but it is her most extensive recollection of her experiences as a scientist. Perhaps because she was speaking to an audience that included many young people, perhaps simply because she was in her beloved hometown, her tone was glowing, almost youthful. She began by expressing her gratitude to the “wonderful development of physics” and the “great and lovable personalities” with whom physics had brought her into contact. She would talk about the things she especially remembered, the things that had formed a “magical musical accompaniment” to her life.

For those of us who are fascinated by physics, Meitner’s talk is a pleasure to read even today. It is remarkable to see how closely her scientific work was tied to the growth of atomic physics, and it is also remarkable to see how many of her teachers, colleagues, and friends were among the leading physicists of their day. In Vienna her professor was the theoretical physicist Ludwig Boltzmann; in Berlin she was introduced to Max Planck and quanta as well as Albert Einstein and relativity; and her own research took her from the early years of radioactivity to the foundations of nuclear physics to the discovery of nuclear fission and beyond. For Meitner, physics was always front and center, and here she gives us a vivid sense of its excitement and joy.

Threading through Meitner’s narrative is a much thinner story of how she achieved a stellar career in a completely male domain. As she tells it, every obstacle ends in success. She remembers how unusual it was “for a girl to attend university lectures at all,” but in Boltzmann she had a brilliant teacher who inspired her to pursue a life in physics. In Berlin in 1907 she found that Max Planck did not favor higher education for women, but five years later he made her his Assistent, her first paid position. And there was Emil Fischer, who did not allow women to even enter his chemistry institute because he feared they would set fire to their hair, but who eventually appointed her to form her own department for physics in the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry, which placed her in the highest ranks of academic science with the authority to pursue her own research. Throughout, Meitner expresses warmth and gratitude toward the influential men who made her career possible. This is not a feminist narrative, however: we learn little about the overall institutional and political changes that were taking place for women at the time, and we do not know if Meitner considered herself a fortunate outlier in a patriarchal structure or someone who opened the way for the inclusion of women into German science. And her story strictly avoids the personal, revealing nothing about the painful insecurity of her early years when she was without position or pay or even prospects.

There is more that Meitner does not tell us. I find it curious that when she is speaking in Vienna, the place she unconditionally loved because it was inseparable from her happy childhood, Lise never mentions her own family, not even her father who supported all his daughters in their pursuit of an education. Did Lise consider it impolite to remind her audience of a family that had vanished from Vienna because every one of them had been forced to flee? Was it taboo to speak openly of the Nazi period or even allude to it? For Lise perhaps it was. We note that she also says nothing about her own frightening escape from Germany, even though she was deeply grateful to her two Dutch friends, the physicists Dirk Coster and Adriaan Fokker, who made great efforts and got her out. Was this taboo as well? Or too painful for Lise to speak or write about in public?

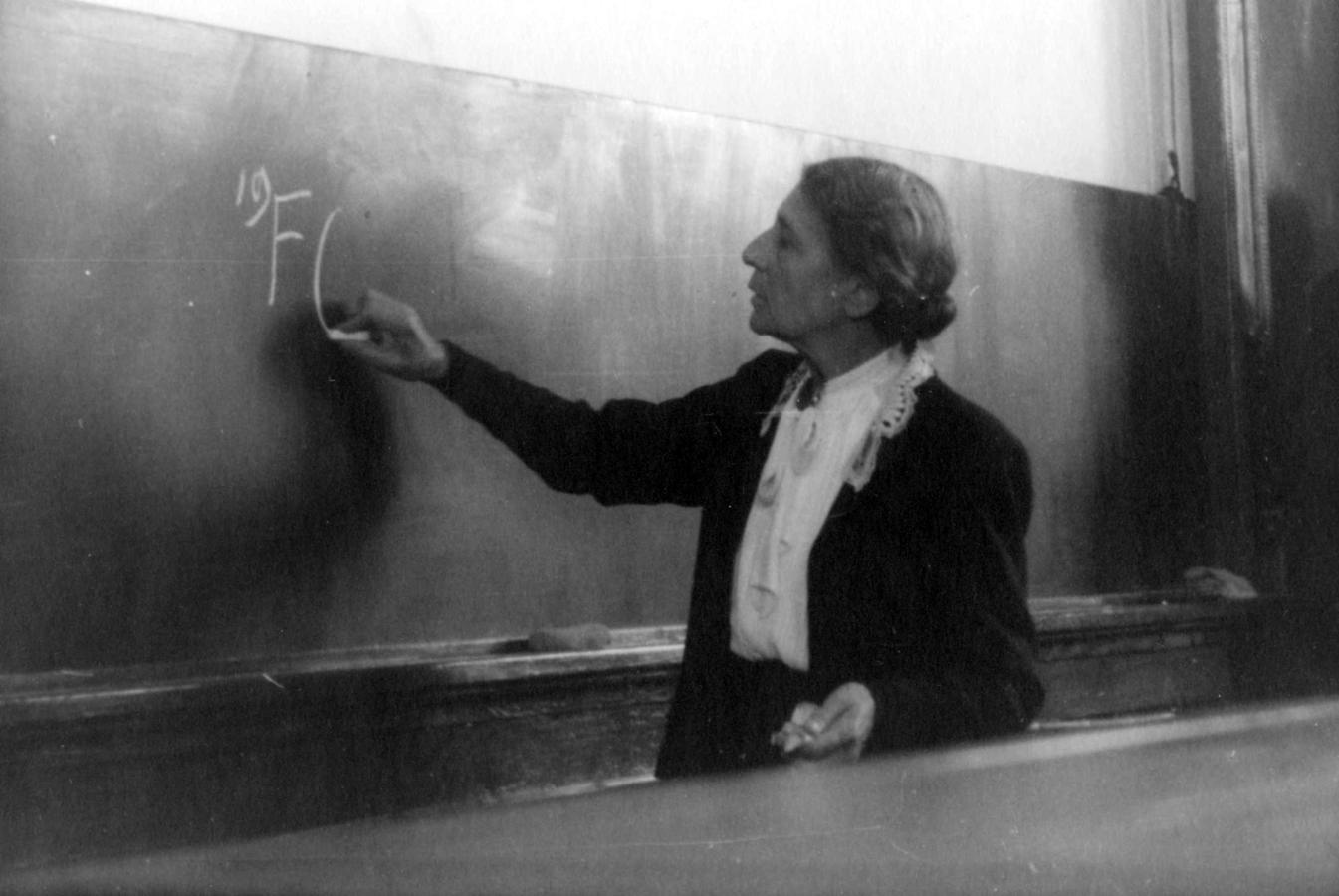

Abb. 2: Lise Meitner 1949 in Bonn. (© Archiv der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Berlin-Dahlem)

This brings us, finally, to Otto Hahn. From Lise’s talk one would never guess that they were once the closest of colleagues and the best of friends, that Lise was godmother to Otto’s son, that she called Otto her Fachbruder. With Planck and Boltzmann and many others, Lise’s tone is consistently warm; with Niels Bohr she speaks of the “magic” of their first meeting and their subsequent friendship. With Hahn, however, there is none of that; she describes their work together in some detail but she is all business, there is no warmth. Clearly the magic of their friendship is gone. But why? As I see it, it undoubtedly goes back to the time just after the discovery of nuclear fission, when Hahn wrongly and dishonestly claimed that Meitner and physics had nothing to do with it. At the time, as we know, she understood that he had political reasons for distancing himself from her, a Jew in exile, but his betrayal damaged her scientific reputation, cost her a Nobel Prize, and eventually diminished her place in the history of 20th century science. In private she reacted with surprise and anger, especially after the war, when Hahn continued to insist that Meitner played no part in the discovery that made him so famous. In public, however, she said nothing, at least not directly, and their friendship continued until the end of their lives. But it was deeply damaged, and I believe this is why Hahn is emotionally missing from Lise’s talk in 1963. In Vienna she chose to remember and be remembered for the joys and successes of her life in physics. As to the rest, Lise Meitner has left us more than enough material to set the record straight.